The Semi-Pro: The Baseball Life of Walter Ancker (Chapter Two)

Chapter 1:

Chapter 1:

The Kid Flinger (1915)

Chapter 2:

Look Homeward, Angel (1916)

—-

The names of five students in the Connie Mack School of Baseball Knowledge were erased from the rolls of the Athletics. The quintet disposed of and their new places of abode are: Pitcher Wilbur Davis, to Atlanta, of the Southern league; Pitcher Walter Ancker, to Asheville, of the North Carolina league; Pitcher Harry Eccles, to the Wheeling Central league team; Third Baseman Harry Damrau, to the Raleigh North Carolina league team, and Shortstop Harry C. Seibold, to the Wheeling Central league team. — Pittsburgh Press, February 28, 1916

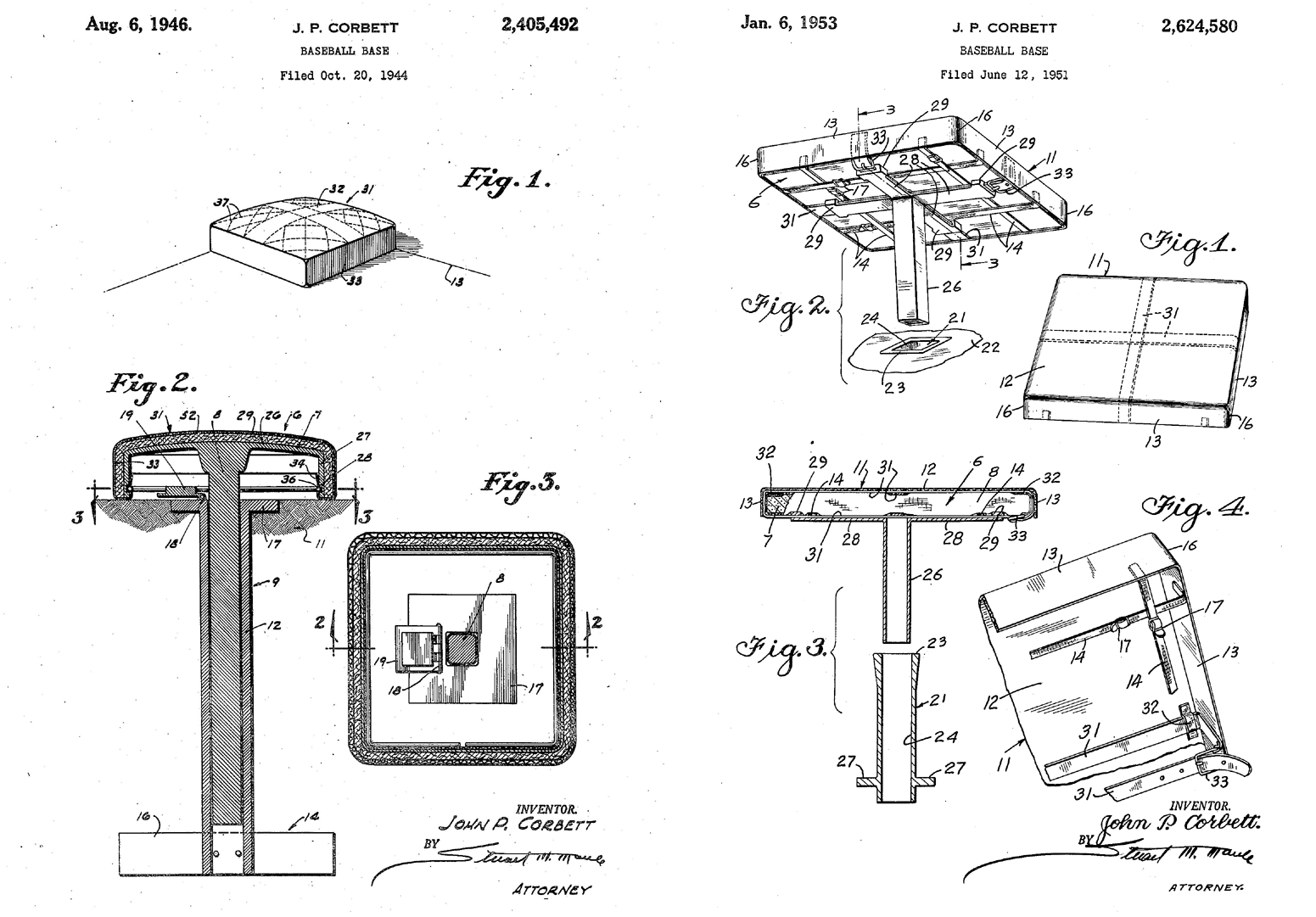

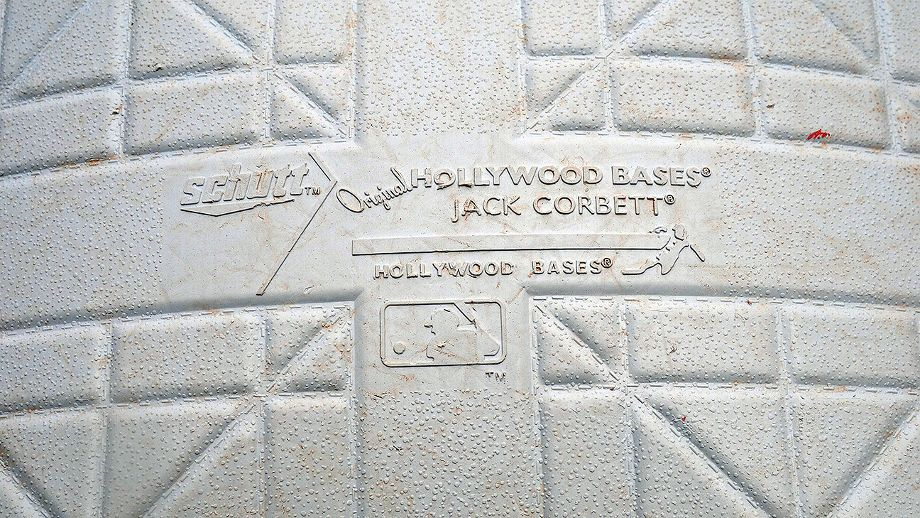

Mr. Mack has no doubt informed you before this that you have been purchased by this club on an optional agreement. We will report here on the first of April and I will forward you transportation or you can pay your own and it will be refunded upon arrival. We allow Pullman and meals enroute in addition to transportation. Would like to hear from you in regard to this date for reporting and any advice as to the transportation requirements you may have, if these are not satisfactory. — Letter from Jack Corbett (Asheville, North Carolina) to Walter Ancker (Closter, New Jersey), March 7, 1916

And like a man who is perishing in the polar night, he thought of the rich meadows of his youth: the corn, the plum tree, and ripe grain. Why here? O lost! — from Look Homeward, Angel by Thomas Wolfe

Southern Railway train No. 15 was closing on the Asheville depot. Walter Ancker, sitting in the green-cushioned seat of a Pullman car, watched the town envelop the tracks with the relief of one who has been traveling for thirty hours and the anxiety of one who has never traveled so far from home. Home was Closter, New Jersey, a hamlet about ten miles northeast of Hackensack in Bergen County. There, Ancker had been the best semi-pro pitcher in the area. Here, he was the new pitcher for the Asheville Tourists, a team in the North Carolina League.

The Tourists were a Class D minor league team, the worst form of baseball one could play and still claim the title of Professional Ballplayer. There were seven rungs on the professional baseball ladder: Major League, Triple-A, Double-A, Single-A, B, C, and D. The lowest rung was D, and that’s where Walter Ancker was. He’d had a quick cup of coffee on the top rung the previous year when he appeared in four games with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. Ancker had shown flashes of competence, but Connie Mack thought he needed more experience before he was ready for another trip to the majors. Ancker needed to tame the wildness that had resulted in a litany of walks, plus a few hit batters and assorted wild pitches. He had perpetually pitched with the bases loaded.

Ancker, two weeks shy of his twenty-third birthday, had departed Closter on Tuesday morning, March 28, 1916. It was difficult to leave. His father had died five years before, and he and his three brothers all worked to support their mother and themselves. Walter’s professional baseball career was about to make a significant dent in the family’s finances. The Tourists would pay Ancker $100 each month. He could make more than that in Closter, playing semi-pro ball and working as an electrician. Ancker promised his brothers that he would come home, and not try to catch on with a semi-pro team in North Carolina, if things didn’t work out in Asheville.

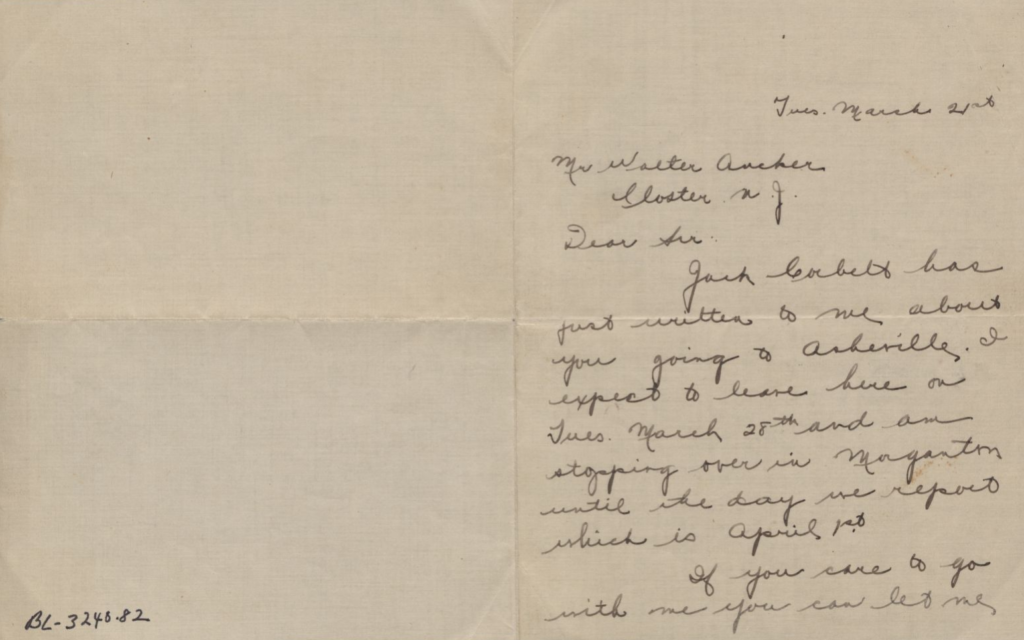

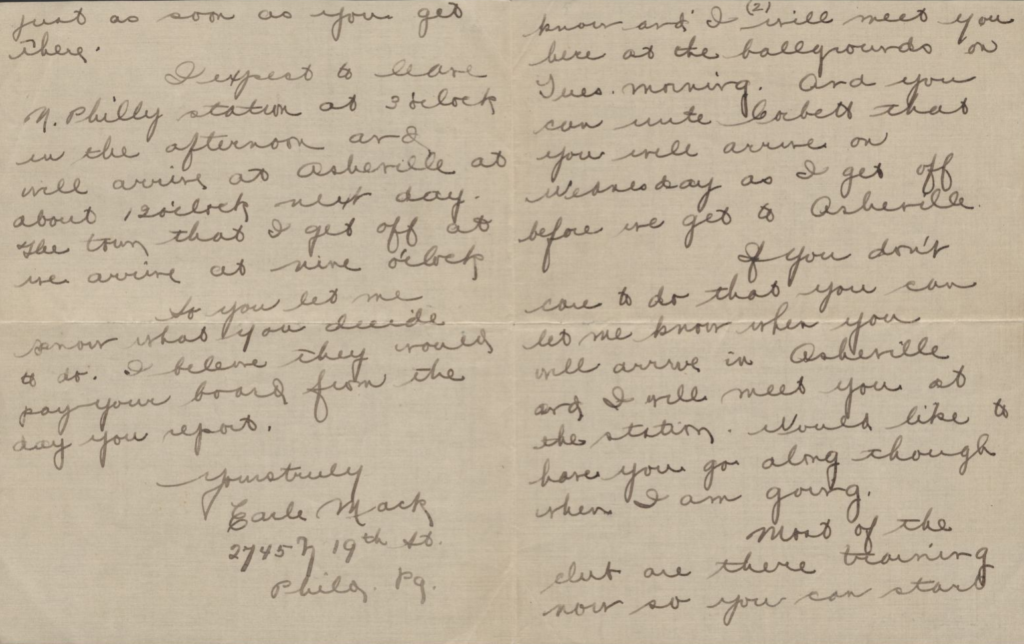

The 107-mile trip from Closter to North Philadelphia Station had taken hours, as the commuter train stopped at every berg and village in the Passaic Valley. Ancker met Earle Mack, Connie Mack’s son and his new teammate on the Tourists, in the North Philly concourse. Mack and Ancker recognized each other readily: they both carried a suitcase and a long cloth bag containing the tools of their trade. Ancker’s bag held a bat, a fielder’s glove, his metal-cleated baseball shoes, a couple of well-worn balls, a cap, and a set of old flannels. Mack’s bag held the same equipment, plus a catcher’s mitt and a first baseman’s glove. Ancker noted that, while his suitcase and Mack’s were equally battered, Mack’s had begun its life as a finer item of luggage.

Page 1 of a letter from Earle Mack (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) to Walter Ancker (Closter, New Jersey) written March 21, 1916. From the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Text of page: Jack Corbett has just written to me about you going to Asheville. I expect to leave here on Tues. March 28th and am stopping over in Morganton until the day we report which is April 1st. If you care to go with me you can let me…

Page 1 of a letter from Earle Mack (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) to Walter Ancker (Closter, New Jersey) written March 21, 1916. From the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Text of page: Jack Corbett has just written to me about you going to Asheville. I expect to leave here on Tues. March 28th and am stopping over in Morganton until the day we report which is April 1st. If you care to go with me you can let me…

Pages 2 (right) and 3 (left) of the letter from Earle Mack to Walter Ancker. Mack suggests that they meet ‘here at the ballgrounds.’ But if Ancker took the train from Closter, they probably met at North Philly station. From the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Text of pages: …know and I will meet you here at the ballgrounds on Tues. morning. And you can write Corbett that you will arrive on Wednesday as I get off before we get to Asheville. If you don’t care to do that you can let me know when you will arrive in Asheville and I will meet you at the station. Would like to have you go along though when I am going. Most of the club are there training now so you can start just as soon as you get there. I expect to leave N. Philly station at 3 o’clock in the afternoon and will arrive at Asheville at about 12 o’clock next day. The town that I get off at we arrive at nine o’clock. So let me know what you decide to do. I believe they would pay your room and board from the day you report.

Pages 2 (right) and 3 (left) of the letter from Earle Mack to Walter Ancker. Mack suggests that they meet ‘here at the ballgrounds.’ But if Ancker took the train from Closter, they probably met at North Philly station. From the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Text of pages: …know and I will meet you here at the ballgrounds on Tues. morning. And you can write Corbett that you will arrive on Wednesday as I get off before we get to Asheville. If you don’t care to do that you can let me know when you will arrive in Asheville and I will meet you at the station. Would like to have you go along though when I am going. Most of the club are there training now so you can start just as soon as you get there. I expect to leave N. Philly station at 3 o’clock in the afternoon and will arrive at Asheville at about 12 o’clock next day. The town that I get off at we arrive at nine o’clock. So let me know what you decide to do. I believe they would pay your room and board from the day you report.

Earle Mack — legally Earle Thaddeus McGillicuddy — had been contacted by Jack Corbett, the player-manager of the Asheville Tourists, regarding Ancker’s journey to Asheville. Mack was coming down from Philadelphia, and Corbett wanted Ancker to accompany him. Mack was an old hand at making the trip from Philly to North Carolina. For the past three seasons he had been the player-manager for the Raleigh Capitals, another team in the North Carolina League. He had signed with Asheville to be closer to the family of his new wife, the former Mary Margaret Cain, who lived 60 miles up the Southern Railway tracks in Morganton. The Cains, even with their solid Scotch-Irish roots, must have thought twice about their daughter now being Mary Margaret McGillicuddy.

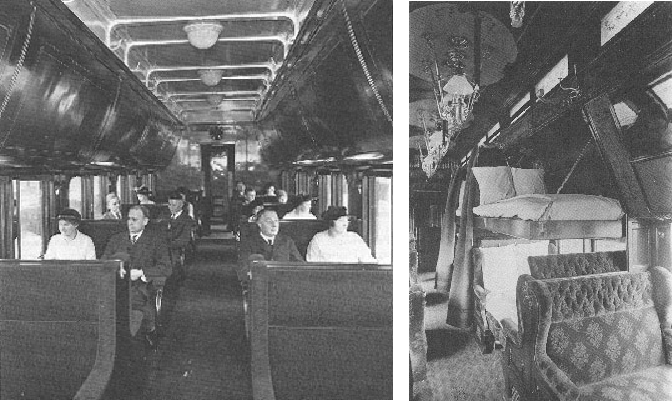

Ancker was grateful to have Mack along as a guide. He could handle the spider web of commuter lines that enmeshed northern New Jersey. But entering a Pullman car was like stepping up from the flat surface of the Hackensack semi-pro diamond to the major league mound of Shibe Park.

The two ballplayers left North Philly station at 3 PM, riding the Southern rails aboard car K-19. They crossed the Mason-Dixon Line beyond Wilmington, and Ancker entered the South for the first time. As the train rattled out of Washington Union Station, Walter saw the Capital just west of the tracks and the Washington Monument silhouetted against the setting sun. He thought about his father, born in Germany, and about his mother, born in America but as German as they came. And he thought about the Senators, eight of whom he had walked back in September in his only major league start.

Somewhere in the Virginia gloaming, Ancker and Mack moved to the club car for a drink while the porter made up their beds, converting their cushioned seats into the lower berth and opening the trap door in the long compartment above the windows where the upper berth lay hidden. Earle Mack must have known their porter from a previous trip because he knew his name: George.

The players returned from the club car, and Mack slid effortlessly between the curtains of the lower berth. Ancker’s situation was more problematic. The rickety ladder that George held in position bowed as Ancker hauled his 190 pounds into the upper berth. Mr. Pullman had not designed the bed with the idea of accommodating a six-foot-one-inch ballplayer, and Ancker had to roll onto his side and pull up his legs to fit. After George closed and tied the curtains, there was the matter of undressing, which in the cramped space required the flexibility of a circus contortionist. Now Ancker understood the old joke, The price for the upper was lower because it was higher. He couldn’t complain, though; the Asheville Tourists were footing the bill, and Mack’s seniority entitled him to the lower berth.

‘Open section’ Pullman cars. Left: Pullman car configured for daytime travel, 1916. Right: Pullman car configured for sleeping, 1890. The seats converted into lower berths, and the upper berths folded down from the compartments above the windows. From Rails West.

‘Open section’ Pullman cars. Left: Pullman car configured for daytime travel, 1916. Right: Pullman car configured for sleeping, 1890. The seats converted into lower berths, and the upper berths folded down from the compartments above the windows. From Rails West.

Ancker recalled one of sportswriter Timothy Murnane’s rules for traveling ballplayers: Don’t continually kick at your luck in drawing an upper berth in a sleeping car. Ancker tried reading a newspaper that someone had abandoned in the club car. General Pershing had chased Pancho Villa into the foothills of the Sierra Madre, and the talk in Washington was of ending diplomatic relations with Germany. But he soon gave it up and extinguished the dim bulb near his head. Murnane had another rule for the situation: Don’t read small print by artificial light, or print of any kind while traveling in the cars.

Ancker fell asleep listening to the rhythmic rumble that would ease Southern Railway passengers into slumber for another half-century.

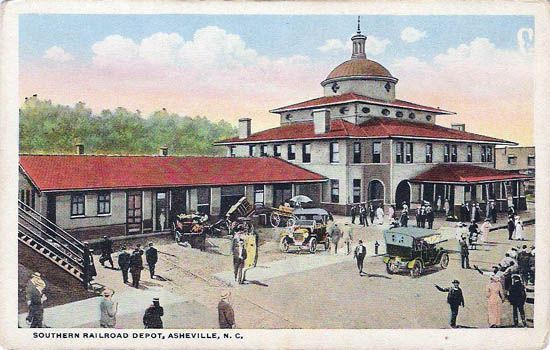

Now, as the train skirted the southern edge of Asheville and turned north into the valley of the French Broad River, Ancker had the two facing seats to himself. Mack had exited the train that morning at Morganton, planning to spend a couple of days with the Cains before joining the Tourists on April 1. At 11:59 AM, the locomotive slowed, the air brakes hissed, and the couplings clanked as the cars compressed together. A beautiful stucco building appeared on the right side of the train.

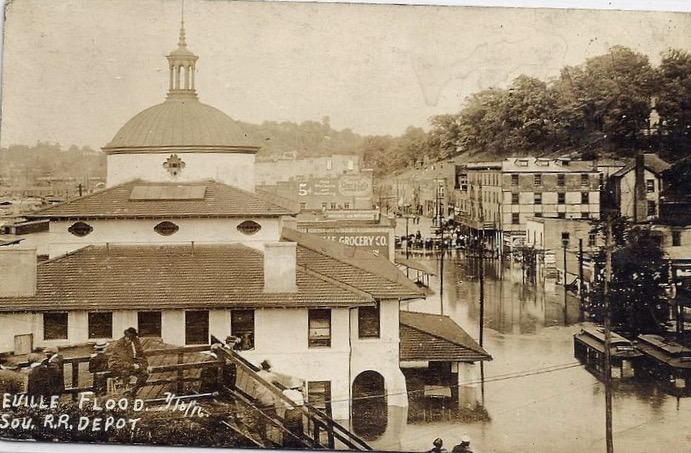

Southern Railway Depot, Asheville, North Carolina. The depot opened in 1906.

Southern Railway Depot, Asheville, North Carolina. The depot opened in 1906.

Ancker stepped down from the car and instinctively clutched the collar of his overcoat. It had been raining and 34 degrees when he left New Jersey. Thirty hours and 700 miles farther south, the temperature was still barely above 40. He looked around for someone who might be Jack Corbett. Instead, a kid, maybe 15 years old, stepped forward and said, ‘Mr. Ancker? Welcome to the Land of the Sky.’

The kid introduced himself as Tommy Wolfe, the Tourists’ batboy. Jack Corbett had dispatched him to collect their new pitcher. Tommy retrieved Ancker’s bags and they boarded a streetcar waiting on the tracks in front of the depot. The conductor bell rang the car to life, and it skittered down Depot Street before turning onto South Side Avenue.

Streetcar in front of the Asheville depot. The sign on the car announces BASE BALL TO-DAY. From Asheville Junction.

Streetcar in front of the Asheville depot. The sign on the car announces BASE BALL TO-DAY. From Asheville Junction.

Ancker glimpsed a slice of a town housing about 25,000 souls. Contrary to what he had been told, most of the inhabitants wore shoes. Tommy said that several players boarded at a house near the ballpark; the club had reserved a bed there for Ancker. Corbett lived in a boarding house operated by Tommy’s mother on Spruce Street. Tommy explained that Corbett was busy, which he said could mean anything from hanging out at the Western Union office to lounging in Mrs. Wolfe’s parlor, entertaining the other guests with tall tales of his life as a ballplayer.

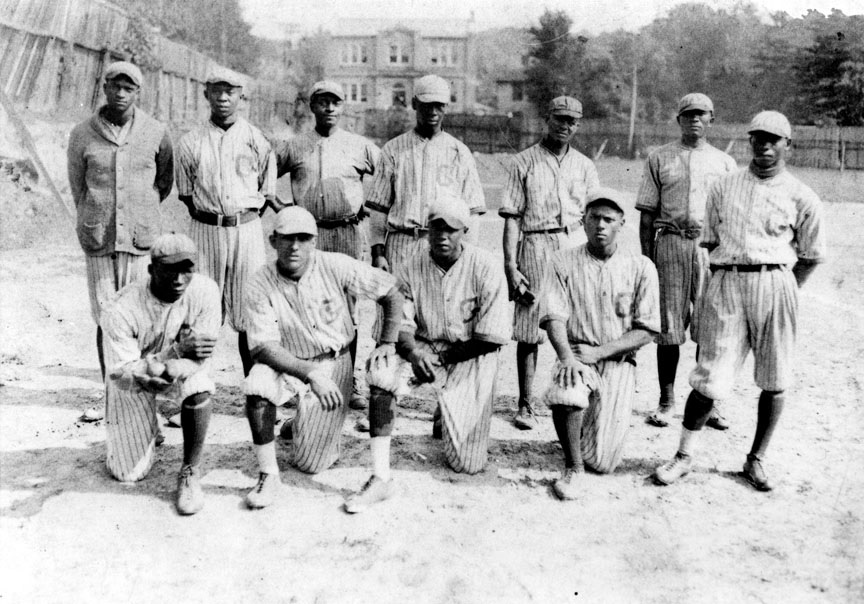

The streetcar braked to a halt and Tommy, then Ancker, stepped off. Tommy walked across the sidewalk and led Ancker through a wooden gate and into what was, apparently, a ballpark. Oates Park was a ramshackle affair of leaning fences, patchy grass, and grandstands that looked like they would fall over in a stiff breeze. It was much worse than Oritani Field in Hackensack. Ancker now fully grasped that he had taken a long slide down from pitching for the Philadelphia Athletics in the concrete-and-steel glory of Shibe Park.

The Royal Giants, Asheville’s first Black semi-pro team, playing in Oates Park around 1916 when the field was only three years old. The umpire (in a white shirt) is standing behind the pitcher’s mound, his usual position when a single official worked the game. The Southside AME Church is behind the first base bleachers, and McDowell Street is behind the third base line. Boys would climb the trees outside the park to watch a game for free. Before 1916, fans were allowed to park their cars inside the park. From the Asheville Citizen-Times.

The Royal Giants, Asheville’s first Black semi-pro team, playing in Oates Park around 1916 when the field was only three years old. The umpire (in a white shirt) is standing behind the pitcher’s mound, his usual position when a single official worked the game. The Southside AME Church is behind the first base bleachers, and McDowell Street is behind the third base line. Boys would climb the trees outside the park to watch a game for free. Before 1916, fans were allowed to park their cars inside the park. From the Asheville Citizen-Times.

Ancker removed his cloth cap, revealing a head of reddish-brown hair, and noted the pitching mound. It was higher than the mounds he pitched from in Bergen County; some of the fields there didn’t have a mound at all. Shibe Park’s foot-high mound had bedeviled him. It messed up all of his angles. He couldn’t get the ball down, and when he tried to force it down, the pitches either hit the dirt or the front of the grandstand. And then there was the problem of his curves not breaking the way they did in Bergen County, hitting the batter instead of the catcher’s mitt. He’d put in some decent innings, just not enough of them. Ancker knew that Connie Mack was right: he needed more experience and he had descended into the baseball basement to find it.

The Asheville Royal Giants posed on the third base side of Oates Park around 1916. Choctaw Street is beyond the outfield fence. From the Asheville Mountain Express.

The Asheville Royal Giants posed on the third base side of Oates Park around 1916. Choctaw Street is beyond the outfield fence. From the Asheville Mountain Express.

‘I thought you might like to see this,’ Tommy said. ‘Is there anything that can evoke spring — the first fine days of April — better than the sound of the ball smacking into the pocket of the big mitt, the sound of the bat as it hits the horse hide? And is there anything that can tell more about an American summer than the smell of the wooden bleachers in a small-town baseball park, that resinous, sultry, and exciting smell of old dry wood? Now if we hurry, we can still catch dinner at the house.’

Tommy turned to exit the ballpark. Ancker followed him, examining the kid with a mixture of curiosity and alarm. Oh Lord, he thought as they passed through the gate. What have I gotten myself into?

And Tommy, having noticed Ancker’s hair, thought about the story he was forming in his mind, the one about the black-haired baseball player who clubs a red-haired rival into submission with his bat.

—-

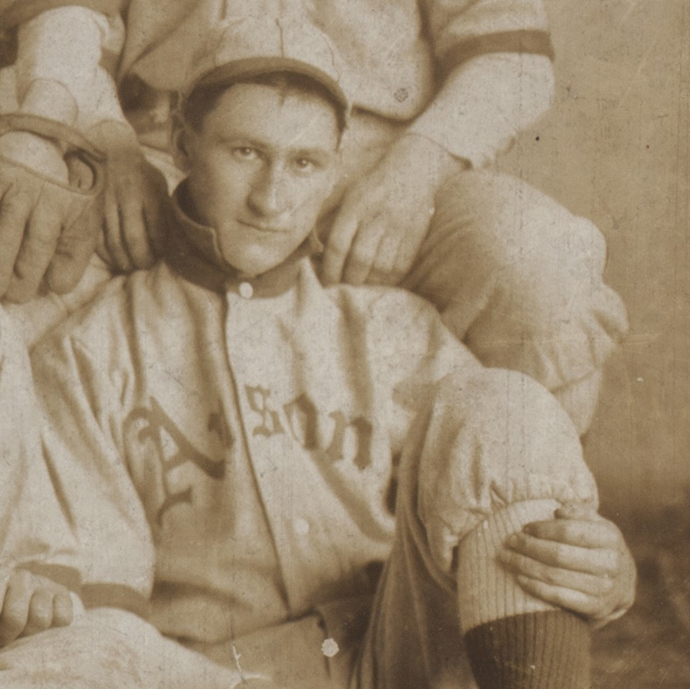

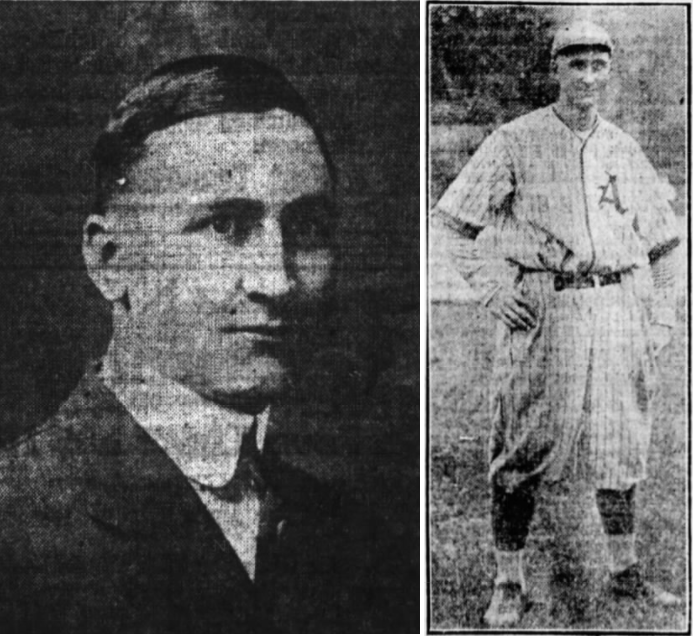

Jack Corbett, from the Asheville Citizen-Times. Formal portrait (left), September 1915. In the uniform of the Asheville Tourists (right), March 1916. Corbett was five feet, nine inches tall, and weighed about 160 pounds. One writer described him as ‘nobby.’

Jack Corbett, from the Asheville Citizen-Times. Formal portrait (left), September 1915. In the uniform of the Asheville Tourists (right), March 1916. Corbett was five feet, nine inches tall, and weighed about 160 pounds. One writer described him as ‘nobby.’

Jack Corbett’s best friend is Jack Corbett; his ideal, Jack Corbett; his criterion, Jack Corbett; and his hero, Jack Corbett. — Winston-Salem Twin-City Daily Sentinel, March 11, 1916

John Philip Corbett was born in Columbus, Ohio, on August 2, 1887. The family moved to Anderson, Indiana, sometime before 1900 when the census caught up with them. ‘Jack’ Corbett’s earliest baseball experiences are undocumented. His obituary stated that he began playing baseball in 1904. A 1914 newspaper article claimed that Corbett ‘piloted an independent ball club several seasons prior to his debut into professional circles.’

The records and newspaper clippings indicate that in 1908, when Corbett was 20 years old, he was playing Class D professional ball. He began that season holding down second base for the Monroe (Louisiana) Municipals of the Cotton States League. Corbett was with the Alexandria (Louisiana) White Sox of the Gulf Coast League a month later. When that club folded in mid-season, Corbett returned to the Cotton States League with the Columbus (Mississippi) Commercials, where he finished out the year.

Thus began a tour of the American South that carried the transplanted Midwesterner from Louisiana and Mississippi to Charleston, South Carolina; Knoxville, Tennessee; Anderson, North Carolina; Spartanburg, South Carolina; and Mobile, Alabama. In 1913, at age 25, he arrived in Asheville.

Corbett’s appearance in Asheville coincided with the opening of Oates Park. The club’s previous park had been adjacent to the river, on a spit of land surrounded by water. The new venue deprived the fans of their favorite means of menacing the umpire. ‘It is generally conceded,’ the Asheville Citizen-Times wrote, ‘that “Put him in the lake” and “Drown him” will no longer be appropriate, since the new baseball plant is some distance from a body of water large enough to threaten the umps.’

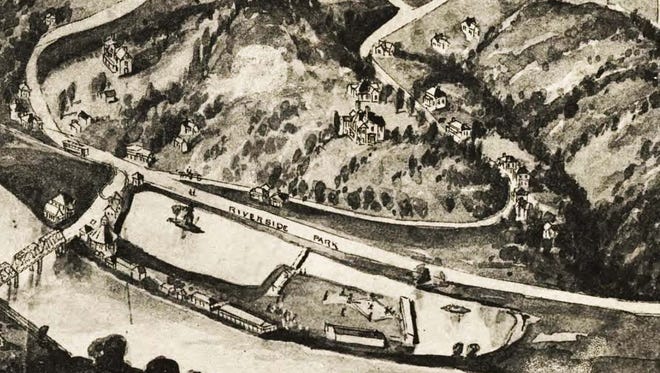

Riverside Park in Asheville, North Carolina, 1912. The baseball diamond is near the bottom of the drawing. Foul balls and home runs often ended up in the water. From the Asheville Citizen-Times.

Riverside Park in Asheville, North Carolina, 1912. The baseball diamond is near the bottom of the drawing. Foul balls and home runs often ended up in the water. From the Asheville Citizen-Times.

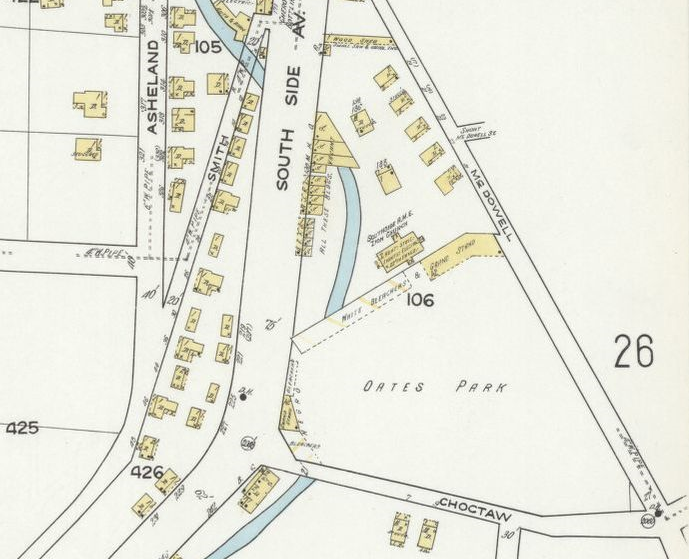

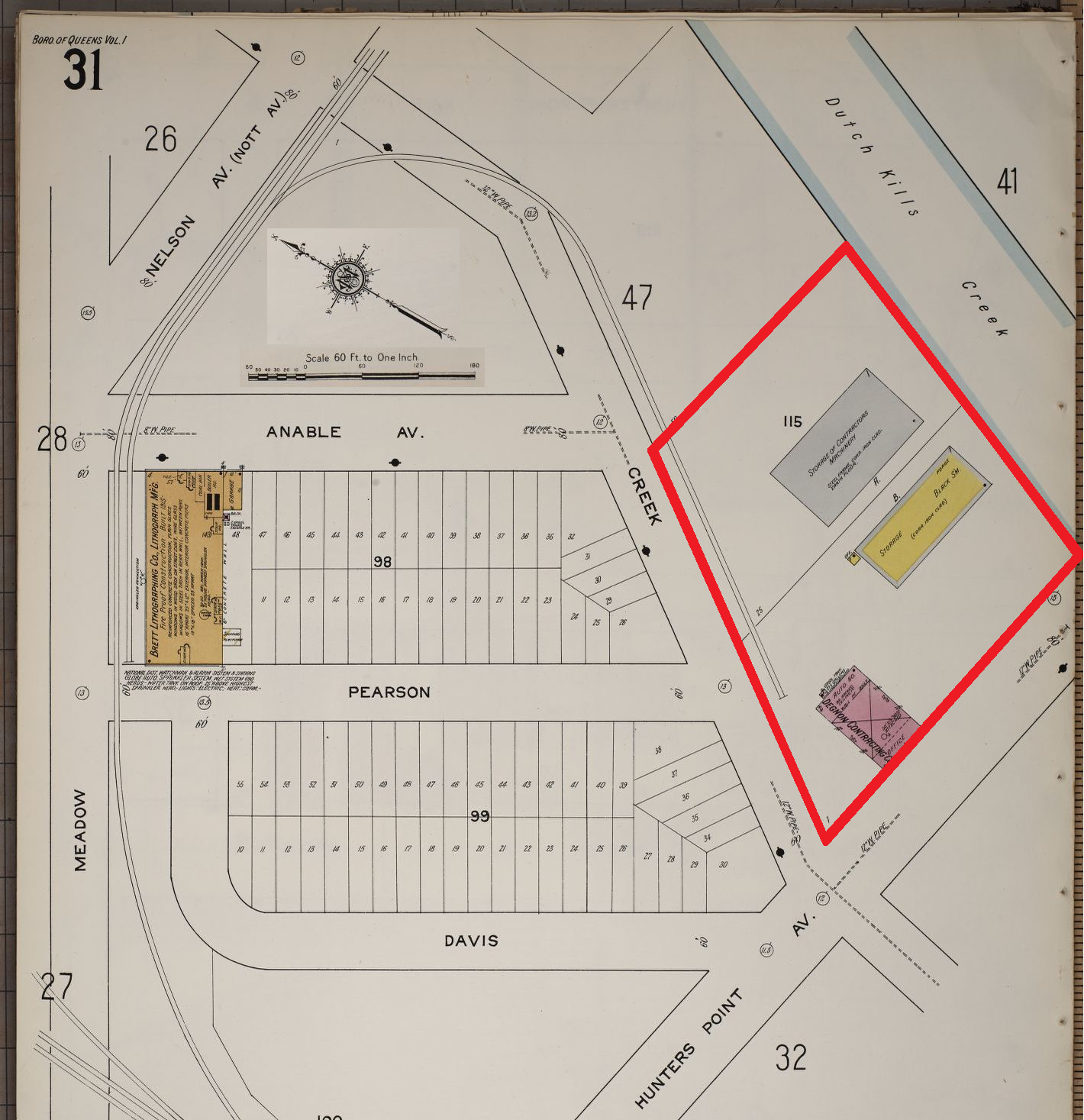

Oates Park was located between South Side, Choctaw, and McDowell streets. Home plate was to the north; the left field corner was at the intersection of Choctaw and McDowell. The bleachers and grandstand on the first base side were for whites; Black fans were seated in the bleachers and grandstands in the right field corner. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for Asheville, Buncombe County, North Carolina, 1917, Sheet 25. From the Library of Congress.

Oates Park was located between South Side, Choctaw, and McDowell streets. Home plate was to the north; the left field corner was at the intersection of Choctaw and McDowell. The bleachers and grandstand on the first base side were for whites; Black fans were seated in the bleachers and grandstands in the right field corner. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for Asheville, Buncombe County, North Carolina, 1917, Sheet 25. From the Library of Congress.

The Asheville Club — referred to in the sports pages as both the Mountaineers and the Tourists, and sometimes as the Paramounts — opened the 1913 season with the ancient, 43-year-old Tommy Stouch managing and playing second base, a job that he performed poorly. If the ball did not bounce directly at Stouch, he would let it roll through the infield for a hit. In late May, the club kicked Stouch upstairs to be Second Vice President; outfielder Lonnie Noojin replaced him as player-manager.

The team finished the year fourth in the six-team North Carolina League. Noojin departed to become the head football coach at Howard College (now Samford University), and Stouch resigned. It was a successful year for Corbett, though, as he finished the season with a .290 batting average and, playing primarily at shortstop, a .904 fielding average.

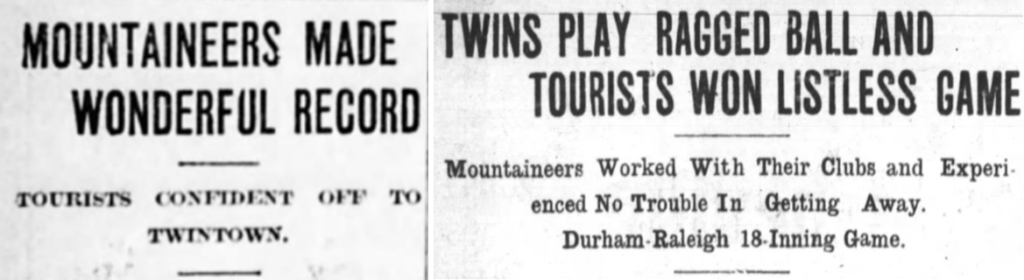

Two articles from the Asheville Citizen-Times, 1913. The article on the left, published July 7, uses ‘Mountaineers’ in the main headline and ‘Tourists’ in the sub-headline. The article on the right, published July 10, uses ‘Tourists’ in the main headline and ‘Mountaineers’ in the sub-headline.

Two articles from the Asheville Citizen-Times, 1913. The article on the left, published July 7, uses ‘Mountaineers’ in the main headline and ‘Tourists’ in the sub-headline. The article on the right, published July 10, uses ‘Tourists’ in the main headline and ‘Mountaineers’ in the sub-headline.

The Asheville club went into the 1914 season with much optimism — as is the grand tradition among baseball’s fans and players. Louis Cook, a 32-year-old infielder who had never risen higher than Class B ball, was hired as player-manager. Cook did not take a great interest in the job. He remained at his home in Illinois until late February, and when he finally showed up in Asheville, Cook spent much of his time coaching the baseball team at nearby Mars Hill College.

In the days before the development of the modern farm system, in which a ‘parent’ major league club provides players to its minor league franchises, each minor league team was an independent operation responsible for scouting and signing its own talent. Cook did not participate in the recruitment process, relying instead on the club’s business secretary, Mr. Thomas M. Duckett, to find suitable players. Duckett cast a wide net, bringing twenty-nine recruits to Asheville. Cook then whittled the crowd down to the thirteen-player limit — including the player-manager — that Class D teams were allowed by the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues.

The Tourists performed miserably. In early June, with the club dead last in the North Carolina League standings and sporting an 11-27 record, Cook resigned. Jack Corbett became the new player-manager. The team performed better under Corbett’s direction but finished last in the league with a 46-74 record. Corbett’s final batting average was .272. His fielding averages were .975 at second base (40 games) and .916 at shortstop (69 games).

Corbett brought an energy to the job that his predecessors lacked. Immediately after the 1914 season ended, the 27-year-old manager went on a lengthy scouting trip to find ballplayers that met his standards, traveling through the North, Midwest, and West. In October, he tagged along with the Cincinnati Reds on a post-season barnstorming tour through small Ohio towns where, the Citizen-Times said, ‘It is expected that many embryo phenoms may be uncovered.’ In late November, Corbett was reported to be ‘in an argument’ with the manager of a Texas League club concerning the services of a prospective pitcher.

Corbett finally returned to Asheville in mid-December. After wrapping up some plans for the coming season, he left for his home in Richwood, Ohio. But he was back in Asheville on December 27, saying that Santa had left ‘a contract or two in his stocking.’

Besides being a player and the team’s manager, Corbett was the Asheville club’s secretary-treasurer and served on its board of directors. He negotiated with major league clubs for exhibition games and planned the Tourists’ spring training in Morganton.

Corbett is maintaining headquarters at the office of Secretary Thomas M. Duckett, in the Westall building, for the present, although he has not regular hours. Most of his business is being transacted over the counters of the cigar stores and around radiators of the drug stores. He admits that he isn’t a very good office man, being too much of a rambler to get his desk cluttered up with papers. His card index system is at the end of his tongue and he carries his plans for the future in his head. — Asheville Citizen-Times, December 30, 1914

The new manager’s efforts paid off. With Corbett playing shortstop, the 1915 Tourists finished at the top of the North Carolina League standings in both halves of a split season, then defeated the champions of the Virginia League in a best-of-seven series. Corbett became known around Asheville as ‘The Tourists’ Guide,’ and the fans presented him with a gold watch.

But a late-season incident demonstrated Corbett’s unwillingness to suffer the slings of those he considered his inferiors. During a September 1 game against Charlotte in Oates Park, the umpire, a former ballplayer who had toiled for sixteen years in the minors named Edward Pleiades Lauzon, handed out several calls that the locals perceived as unjust, raising the ire of the fans and, in particular, of Jack Corbett.

Asheville was trailing 1-3 in the ninth inning with a runner on first base and no outs. The Tourists’ batter smacked the ball down the right field line, moving the runner to third. But Lauzon ruled it a foul ball, sending the runner back to first. Corbett, coaching third base, protested vigorously and was ejected from the game. The batter returned to the plate and promptly struck out, and the next hitter flied to left. The following batter lined a double into the left field corner, scoring the runner from first. If the previous foul ball had been ruled fair, the double would have scored two runs to tie the game. With the tying run now at second, Asheville’s last batter struck out to end the ballgame.

‘After the game,’ according to the Asheville Gazette-News, ‘a mob of incensed fans rushed onto the field to attack the umpire, but Chief of Police L.E. Perry and some of his policemen were “Johnnies on the spot” and “The Honorable Mr.” Lauzon probably has to thank the Asheville constabulary that he escaped personal injury.’

Corbett confronted Mr. Lauzon and, in the sanitized words of the Citizen-Times, made ‘statements to him’ that ‘were most uncomplimentary and exceedingly insulting.’

The umpire fined Corbett $35. North Carolina League president Arthur Lyon upheld the fine and ordered Corbett to apologize to Lauzon. Corbett refused to remit either the fine or the apology, and Lyon suspended him for the remainder of the season. Although unable to take the field, Corbett continued to direct the club as its ‘Business Manager.’

Kicking — showing displeasure at the umpire’s calls — was a habit with Corbett, one that he elevated to performance art involving the entire team. A 1916 item in the Charlotte News offers an insight into the Tourists’ antics: ‘On every pitch that comes within reaching distance of the catcher that is called a ball by the umps, Corbett takes off his glove and looks to Hickman. Hickman yells. Bradshaw takes off his glove and stares. Bitting takes off his glove, walks around a bit and throws an imaginary pebble over toward the bleachers. Mack can’t figure out why so he does an Indian war dance. If Asheville would cut out a bit of their kicking — if Asheville would only cut out their unnecessary kicking, the towns around the circuit would take much more delight in seeing them come for a three-day engagement.’

Jack Corbett’s love of theatrics and his intolerance of perceived inferiors would claim another victim in the form of Walter Ancker.

—-

It is unclear how the Asheville Tourists acquired Walter Ancker’s contract from the Philadelphia Athletics or whether Corbett personally met and worked out Ancker before purchasing his contract from Connie Mack.

After the 1915 season ended, Corbett journeyed to the Northeast, where he watched the World Series games between the Philadelphia Phillies and the Boston Braves and met with the managers of multiple major league clubs. He returned to Asheville on October 19 and announced that he had acquired the contracts of ‘a number of new men,’ but that he was not at liberty to reveal their names. Corbett likely visited Connie Mack on this trip; he was a good friend of Earle Mack and had served as the best man at Earle’s wedding on September 28, 1915. At Connie Mack’s suggestion, Corbett may have taken the train to Hackensack to see Ancker in action.

While Corbett was on his northeastern tour, Ancker pitched for the Tenafly Baseball Club in a Columbus Day exhibition game against the Oritani Field Club. Ancker struck out sixteen or seventeen batters (depending on which newspaper one subscribed to) and gave up three hits and no runs. Oritani’s pitcher, major leaguer Harry Harper, pitched a no-hitter. The game ended in a 0-0 tie as darkness loomed. Four days later, Ancker pitched for a team of local all-stars against a barnstorming squad led by future Hall of Famer Rube Marquard. Ancker allowed one run, two hits, and struck out nine as the All Stars downed the ‘cracks’ 2-1. If Corbett witnessed either of these games, he might have been impressed enough to purchase Ancker’s contract from the Athletics.

In late 1915 Corbett confided to a reporter with the Citizen-Times that a major league team had promised to supply two pitchers to the Asheville club. The plan was for Corbett to ‘visit the spring training camp of the big league team in question, and when the manager of that team decides what pitchers he wants to retain, Manager Corbett will be given first pick of those to be “farmed” for the next season.’

A subsequent story in the Citizen-Times, published March 31, 1916, mentioned that Ancker ‘is in good playing condition, having been with Connie Mack’s Athletics on their training trip.’ And an April 5 article in the same paper claimed that Ancker ‘has been training with Connie’s bunch down among the sweltering pines.’ Based on this information, one might surmise that Corbett observed Ancker at the Athletics’ spring training camp in Jacksonville, Florida, purchased his contract there, and brought him to Asheville.

But the Ancker-was-in-Florida theory doesn’t hold up. Connie Mack announced Ancker’s sale to the Tourists on February 28. The Athletics’ pitchers and catchers departed for Florida, by steamship, on March 8 (pitchers and catchers, by longstanding tradition, opened spring training a week before the arrival of infielders and outfielders). Ancker was not among the departees listed in a Philadelphia Inquirer article about the trip.

When Corbett wrote to Ancker on March 7, he addressed the letter to Ancker’s home in Closter, New Jersey. And Ancker and Earle Mack left Philadelphia for Asheville on March 28. The Citizen-Times sportswriter was probably mistaken or misinformed about Ancker being in Florida. Hearing that Ancker ‘had been with the Athletics,’ and being aware of Corbett’s plan to capture pitchers in Florida, he may have stumbled to the incorrect conclusion that Ancker had been at Connie Mack’s spring training camp.

—-

The Tourists were struggling financially, as were most minor league teams of the era. To hold down expenses, Corbett brought a minimal number of players to spring training. He announced that the preseason squad would comprise ‘not over fifteen men.’ But even with a slimmed-down training camp, the cost of transporting the men to Asheville, and paying their room and board, represented a significant expense for the cash-strapped club.

The Tourists offset their spring training costs by selling books of regular-season tickets. A book of twenty-five children’s tickets cost $1.00, and a book of twenty-five ladies’ tickets cost $2.50. For men, a book of four tickets cost $1.00, which was not a bargain since the regular price of admission to Oates Park was 25 cents. The plan demonstrated Corbett’s canny marketing genius: lure the wife and kids to the park with discounted tickets and make the husband — who was obligated to escort his family — pay full price.

The Asheville fans got their first formal views of Corbett’s new 1916 Tourists in a pair of exhibition games, played in Oates Park on April 5 and 6, against the Philadelphia Athletics. Connie Mack was not with his barnstorming squad — dubbed the Yannigans, a now-obsolete term for scrubs or rookies — having entrusted its care to coach Ira Thomas.

Connie Mack was still stirring his pot, attempting to create a winning combination using raw rookies and cast-offs. The only face on the Yannigans that was familiar to Ancker was forty-one-year-old Napoleon ‘Larry’ Lajoie, commencing his twenty-first and final major league season. Ancker may have been glad to see the infielder who had played behind him when he pitched for the Athletics. But he ruefully remembered the grounder Lajoie booted in Ancker’s start last fall against the Senators. A putout would have ended the inning. Instead, the error unnerved Ancker and opened the door for a single, two walks, a wild pitch, two unearned runs, and Ancker’s banishment to the bench.

Corbett did not use his regular pitchers against the Athletics. He recruited local talents, a stunt guaranteed to attract spectators to Oates Park. In the April 5 game, the Athletics faced Harry Allison, a high school hurler; Cecil Bryson, a semi-pro southpaw from the nearby town of Sylva; and a cadet from Bingham Military School named Bland. The David vs. Goliath match-up drew 1000 fans on a chilly Wednesday afternoon, including, the Citizen-Times’ reporter observed, ‘a large number of the fair sex.’ The assembled masses watched the Tourists lose to the big leaguers 2-3 in a game called after eight innings due to encroaching darkness.

Between the third and fourth innings, Mr. L.L. Jenkins, president of the Asheville club, appeared on the field wearing a Tourists uniform and invited everyone in attendance to a ‘monster banquet’ to be held that night at the Langren Hotel.

Jenkins expected a crowd of 300, but only 100 turned up. Those who attended enjoyed a fine meal in the hotel’s main dining room, serenaded by the Langren orchestra. A parade of twenty-seven speakers passed the podium, including President Jenkins — who urged the attendees to buy the bonds he had issued to finance the team — along with several local businessmen, Jack Corbett, and players from both the Athletics and the Tourists. Walter Ancker was listed last in the Citizen-Times’ review of the event, probably indicating his order in the program. There is no record of Ancker’s remarks or the number of attendees still present and awake to hear them.

Attendance was down for the Thursday game, with only 600 souls in the grandstand. Corbett again sent Allison and Bryson to the mound. Harry Watson, a former Asheville pitcher, also made an appearance. The faithful witnessed another defeat, with the Tourists losing 2-6. Ancker made it into the game, pinch hitting for Earle Mack — and recording an out — in the ninth inning.

An incident in the top of the seventh inning added some amusement. After the Athletics made their third out, a new Philadelphia batter stepped up to the plate. Allison prepared to pitch to him, both batter and pitcher unaware that the side had been retired. The umpires for the game, Asheville pitchers Ernie ‘Doc’ Ferris and George ‘Doc’ Lowe, were equally oblivious. The scorers in the press box tried to get their attention, but it required the shouts of the spectators to bring the inning to its proper close.

George Lowe was probably known to Ancker prior to his arrival in Asheville. He was a Bergen County boy from Ridgefield Park. Though two years older than Ancker, he and Ancker had surely crossed basepaths around Hackensack before both arrived in Asheville; they would meet again in Hackensack later in 1916.

On the Monday following the exhibition games, sportswriters — and other loafers who had nothing better to do on a weekday morning but hang around Oates Park — witnessed a mound session by Ancker and Jack Harper, a pitcher whose fate intertwined with Ancker’s.

Harper had been, like Ancker, one of Connie Mack’s 1915 kid flingers. His cup of coffee with the Athletics was even briefer than Ancker’s. Harper appeared in three early-season games, pitching a total of eight-and-two-thirds innings. Harper was already well-known in Asheville, having previously pitched in the North Carolina League for Greensboro and Raleigh.

After witnessing the workout, an anonymous reporter for the Citizen-Times declared that the two pitchers had ‘everything in the world.’ He judged that Harper was ‘better this year than last.’

The writer was impressed with Ancker’s size: ‘Ancker is an ideal pitcher. He is big and husky, built for plenty of work, has a wealth of smoke and an assortment of curves that promises to keep the Carolina batters reaching in vain throughout the season.’

Oates Park needed repairs before the season opened, so Corbett’s club decamped for Gastonia on Wednesday morning, April 12. President L.L. Jenkins was a native of the town, with interests there in textile mills, banking, and politics. Jenkins arranged for the Tourists to train at Gastonia’s Loray Park.

Loray Park was more run-down than Oates Park, featuring a large gap in the center field fence. During a game the previous year, the grandstand had been rumored to be on the verge of collapse. ‘The infield here is not the best that there is,’ the Citizen-Times complained, ‘but this is being treated by several men each day and will soon be in good shape.’

The day after their move to Gastonia, the Tourists played an exhibition game against the Columbia Comers of the Class C South Atlantic League. Six hundred fans saw Asheville lose 6-8. Walter Ancker started the game for Asheville, earning the distinction of being the first regular Tourist pitcher to take the mound in 1916, and was relieved by Doc Ferris. The published box scores are incomplete, but Ancker probably pitched five innings, gave up two runs, struck out three, and walked one. The Citizen-Times reported that ‘Ancker went good.’

Columbia scored a two-run homer off Ancker in the second inning when, with a runner on second, a ball rolled through the hole in the center field fence. Today the hit would be a ground rule double. But in 1916, any ball that bounced over or rolled through the outfield fence was a home run. Ancker reclaimed a run for himself in the following inning when he poled a legitimate homer over the right field fence.

Corbett, as usual, took umbrage with the umpire, a local man named Miller, and argued a ninth-inning call at second base so strenuously that Mr. Miller fled the field in fear for his safety.

The Tourists played another exhibition game against the Comers the following day, with Jack Harper and George Lowe pitching for Asheville before an audience of 300. High winds created a minor dust storm in the grassless Loray Park. A similar gale had blown in a game the previous month, kicking up a cloud of sand so thick that the spectators in the grandstand could not see the infielders.

Another problem for Corbett was an injury to his second baseman, Dallas ‘Rabbit’ Bradshaw. For unknown reasons, Corbett borrowed an infielder from the Comers. The conscript made several ‘errors’ and, when he did field the ball, refused to throw it anywhere. The game ended after seven innings with the score tied 7-7.

Asheville’s final game in Gastonia took place on Saturday, April 15. The Tourists took on a patched-together squad comprising five Columbia players, two Asheville players, and various local talents. Details of the bout have not survived, but Asheville left the field with a 12-3 victory.

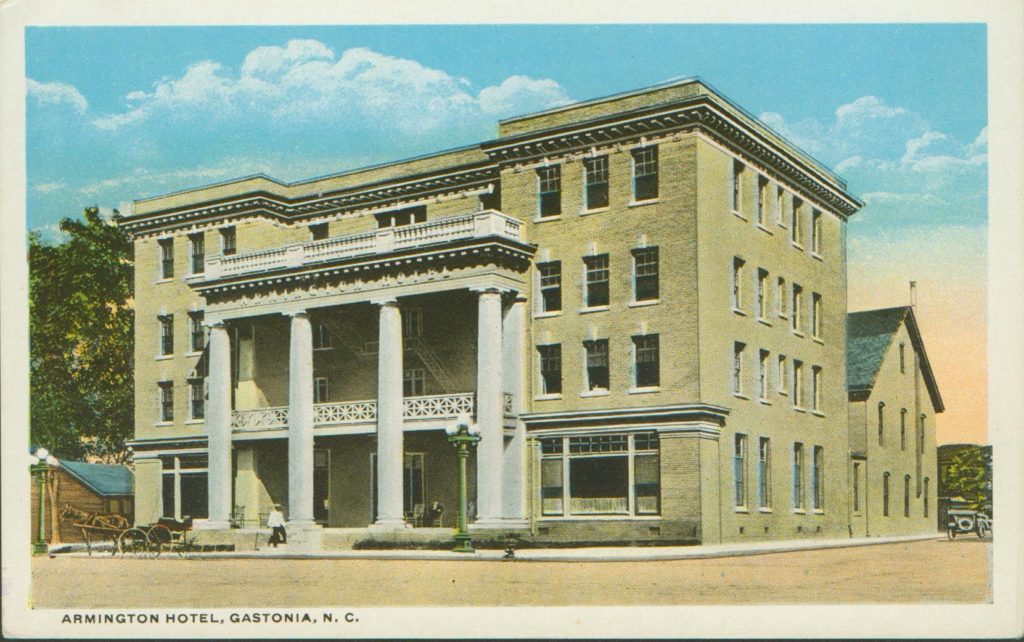

Armington Hotel, Gastonia, North Carolina, 1915.

Armington Hotel, Gastonia, North Carolina, 1915.

The Tourists stayed at the Armington Hotel during their sojourn in Gastonia. On the Sunday evening before their departure, the hotel manager treated the team to a complimentary dinner with menu items named for the players. The meal included Corbett Cocktail, Queen Lowe Olives, and Harper Brew (coffee). The entrée, Prime Cut of Roast Beef a la Bitting, honored Earl Bitting, the Tourists’ third baseman and cleanup hitter.

The chef was not a fine student of the game. He transformed Earle Mack into his three-year-old half-brother in the form of Connie Mack, Jr. Rolls. Regarding Walter Ancker’s role in the affair, the Citizen-Times wag who was following the team noted, ‘It is not believed that the promising new twirler is green, albeit his name was presented as “Ancker Salad.”‘ And perhaps proving that he had imbibed too many Corbett Cocktails, the writer included this cringeworthy tidbit about the team’s first baseman, rookie Ernie Burke: ‘The author of the menu, evidently was wised to the new Asheville first sacker’s fondness for members of the fair sex, for his name appeared as “Young Chicken Burke Dressing.”‘

The Tourists returned to Oates Park for two games against Tennessee’s Maryville College. The Maryville team was fast — meaning a very good baseball club. Some of its players were not, in the strictest sense of the word, amateurs. Their pitcher in the first game, an Alabama boy named J. Frank Whitney, had been signed by the Birmingham Barons of the Class A Southern League in 1913. The Barons sold his contract to the Newnan (Georgia) Cowetas of the Class D Georgia-Alabama League, where he pitched in 1914 and 1915, compiling an 8-7 record in the latter season.

In July 1915, a group of baseball fans in Gastonia, wishing to get in on the action of the three-team semi-pro Western North Carolina League (comprising Morganton, Statesville, and Lenoir), formed the Gastonia Athletic Association. They secured the services of the Newnan Cowetas — the struggling Georgia-Alabama League having completed a truncated season — and shipped the entire lot, including J. Frank Whitney, to Gastonia via the Southern Railway.

The ‘new’ team, christened the Gastonia Tigers, finished first in the Western North Carolina League in the second half of the split season. The Tigers then beat Morganton, the winner of the season’s first half, in a best-of-three series to take the pennant.

Chief Bender, who had already played twelve years with the Philadelphia Athletics and who had never appeared with the Tigers, pitched a complete-game victory in the series opener. The next day he came on in relief of Whitney, who left in the seventh inning with the Tigers leading, and finished the game without yielding an additional run. It was perfectly acceptable for a future Hall of Famer to show up and pitch in a semi-pro league’s championship series.

How Frank Whitney (or Bill Whitney, as the Gastonia and Tennessee newspapers called him) ended up pitching for Maryville College, and whether the school paid him for his efforts, is a mystery. At any rate, he pitched a 16-inning complete game against the Tourists but lost 5-6 as Corbett sent Ferris and Olin Perritt to the mound. The collegiates won the second game, 7-3, with Harper and Lowe pitching for Asheville.

Miss Helen Keller arrived in Asheville on Thursday, April 20, to deliver a lecture on Happiness. Billed as ‘The World’s Eighth Wonder,’ she was on a tour of North Carolina cities, accompanied by her teacher, Mrs. Anne Sullivan Macy. A witness to her lecture in Charlotte considered the evening to be a life-changing event, declaring ‘none who had that experience can ever be quite the same afterwards as before.’

Asheville’s final exhibition game took place April 22 on a pleasant Saturday afternoon with temperatures in the low 60’s. The Tourists plastered the cadets of Bingham Military School 15-4. Ferris started for the Tourists, with Ancker and Lowe following in relief. Ferris allowed two runs in the second inning, and the cadets tagged Ancker for two runs in the seventh. Bingham recorded a total of four hits, one being a triple.

Asheville went into the regular season with a pitching staff comprising Ferris, Harper, Perritt, Lowe, and Ancker. Perritt, who could catch and play the field, was also the team’s utility man. The Greensboro Daily News recognized that Ancker was at the bottom of the rotation: ‘The fifth member of the hurling corps, Ancker, was secured from Connie Mack. He has an excellent fast ball and his curve, or hook, is breaking nicely. Corbett is positive that Ancker will be a winner with the Paramounts, but for that matter he feels the same about the other four.’

—-

Cone Park in Greensboro. There appear to be animals — possibly goats — along the first base line. From Old Time Baseball Photos.

Cone Park in Greensboro. There appear to be animals — possibly goats — along the first base line. From Old Time Baseball Photos.

The North Carolina League commenced its 1916 regular season on Wednesday, April 26, with games in Durham, Charlotte, and Greensboro, where the Tourists took on the Patriots (usually called the Goats). Plans called for new Saxon automobiles provided by the Paige Sales Company to carry the players from the Clegg Hotel through the business district to Cone Park.

‘The game this afternoon will start at 4 o’clock,’ predicted a cynic at the Greensboro Daily News, ‘and some distinguished citizen will probably walk out into the middle of the diamond and throw the ball in the general direction of home plate.’ The previous year in Winston-Salem, the mayor, Mr. O.B. Eaton, had been the designated distinguished citizen. He proceeded to heave the ball over the grandstand.

A drizzling rain put a damper on the festivities. The parade was reduced to a quick ride from the hotel directly to the ballpark, where 700 fans saw the Tourists down the Goats 6-2 with Ferris pitching a complete game. The Tourists followed it up the next day with another win against the Goats, 9-6, as Harper also pitched a complete game.

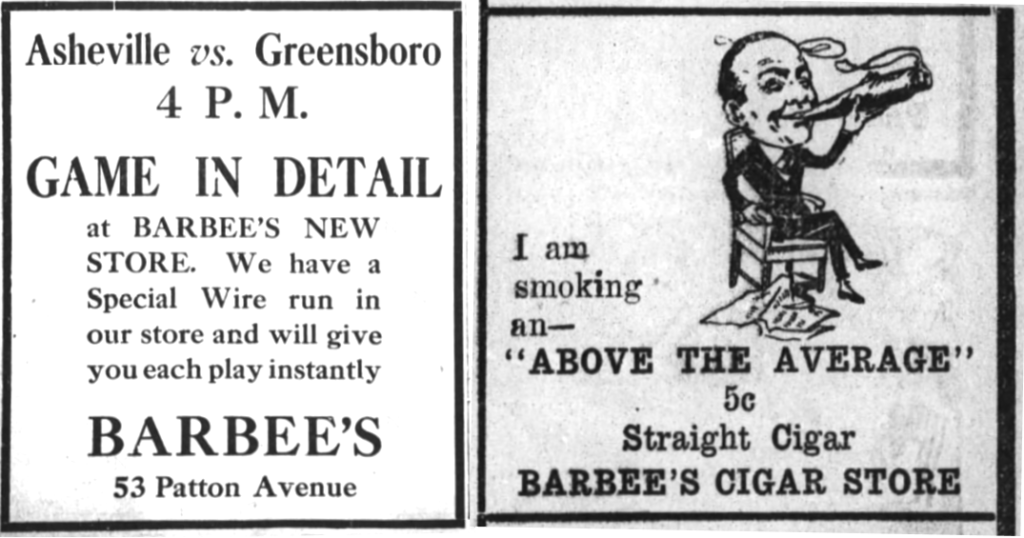

Advertisements for Barbee’s Cigar Store in the Asheville Citizen-Times, 1916. The store held its Grand Opening on April 13, offering a ‘REAL Cigar’ for each man who entered and a box of candy for each lady. An orchestra serenaded the visitors.

Advertisements for Barbee’s Cigar Store in the Asheville Citizen-Times, 1916. The store held its Grand Opening on April 13, offering a ‘REAL Cigar’ for each man who entered and a box of candy for each lady. An orchestra serenaded the visitors.

The club returned to Asheville for their first home game, and 1,967 fans packed into Oates Park on a Friday afternoon to see the Tourists take on the Charlotte Hornets. Those locals who were not inclined to attend in person followed the action in the brand-new Barbee’s Cigar Store, where a Special Wire brought the results of each at-bat. The faithful fans who filled the park got their money’s worth, witnessing a 15-inning, three-hour marathon that began at 4 PM and ended just fifteen minutes shy of sundown. The hometown boys lost 4-6 behind the pitching of Perritt and Lowe.

Walter Ancker finally saw regular-season action on Saturday, April 29, against Charlotte. If Corbett was using a five-man rotation (Ferris, Harper, Perritt, Lowe, Ancker), then Ancker should have started the game. Instead, Corbett skipped back to Doc Ferris, using Ancker as a reliever.

The game was covered for the Citizen-Times by Mr. L.M. Cadison, a former reporter, sportswriter, and business manager with the Pittsburgh Press who had relocated to Asheville. Describing the performance of starting pitcher Ferris, Cadison pulled out all the stops: ‘Commander Corbett selected Doc Ferris, who won the opener in Greensboro last Wednesday, to do the twirling honors here yesterday afternoon, but the terrible home-run inflicting bombardment sent the Doctor to the discard in the early part of the sixth chapter. It was not a day for Ferris — that is all there is to it. My what a terrific fusillade of hefty swats met the delivery of the physician. Right on the jump he got himself in hot water and remained submerged until Captain Corbett had compassion on the victim, and incidentally on the fans, and delegated him to the cool showers.’

With no outs and Asheville trailing 7-8 in the top of the sixth inning, Ferris having just given up a two-run homer, Ancker entered the game and struck out the side. Mr. Cadison felt that Ancker ‘made a very favorable impression.’

The eighth inning was a different story, one of those Walter Ancker Specials that had haunted him the previous year in Philadelphia. After striking out the leadoff batter, Ancker surrendered a walk, a double, an infield hit, and a wild pitch. After an error by Corbett, the carnage continued with a single, a flyout, and another single. The Good Mr. Cadison did not reveal how the inning ended, but Ancker gave up three runs before leaving the mound. Ancker was still in the habit of pitching well in one inning, then completely melting down in the next.

The game ended with Asheville winning 12-11. By today’s rules, Ancker would receive the win, having entered the game with the Tourists losing. Pitching the final four innings, Ancker gave up three runs and seven hits, struck out five, and walked four. The writer for the Greensboro Daily News was less than dazzled: ‘As a hit fest the game was a masterpiece; as a baseball game it was horrible exhibit No. 1… Not one of the four pitchers used was effective.’

With the initial games of the season behind them, the teams of the North Carolina League took up their usual routine: two three-game series each week, Monday through Wednesday, and Thursday through Saturday. There were no games on Sunday as the Blue Laws in most southern towns prohibited businesses from operating and because ballparks were generally acknowledged to be dens of iniquity.

The Tourists’ first three-game series was a road trip to Durham with complete games by Harper (lost 1-7), Lowe (won 4-2), and Ferris (lost 1-13). Moving to Winston-Salem, Perritt lost a complete game to the Twins, 7-8. Ancker made his first regular-season start the following day, Friday, May 5, in front of 900 fans in the Twins’ Prince Albert Park.

The first seven innings were Ancker’s typical blend of wildness and grit. He gave up seven hits, walked five, and a hit batter. The Twins had runners incessantly on base, but Ancker surrendered only a pair of runs, one in the fourth inning and another in the sixth.

Ancker walked to the mound in the bottom of the eighth inning with the score tied 2-2. He then handed the Twins the proverbial Big Inning, the inning that Walter Ancker experienced in almost every professional game. He plunked the first batter on the arm, got the next man on an outfield fly, then gave up a double and a home run for a three-run inning. Asheville plated a single run in the ninth, and the game ended in a 3-5 loss for the Tourists. The final line for Ancker: five runs, ten hits, three strikeouts, five walks, and two hit batters.

The Twins started Johnny Meador, who was replaced in the second inning by Whitey Glazner. The Citizen-Times reporter panned Ancker and Glazner equally: ‘Both Ancker and Glazner were rather free with the passes, the Twin pitcher walking five men [the box score indicates four walks by Glazner and one by Meador] and the Asheville slab performer granting five free tickets to first, besides hitting two Twin players by way of diversion.’

The loss could not have made Jack Corbett happy. Corbett valued pitchers who could ply their trade consistently, walking few and piling up the innings. He wasn’t looking for Walter Johnson. He just needed pitchers who could hold the lid down long enough for the Tourists to string together a few runs. Walks, hit batters, and wild pitches were signs of imperfection, even weakness.

There was something uncanny about the predictability of the Walter Ancker Special, the Big Inning in which Ancker would suddenly forget how to pitch. A great pitch and a terrible pitch are differentiated by tiny tolerances in the combinations of force, finger position, and release point. Ancker could, usually, produce combinations that created good-if-not-great pitches. But, given enough time, Ancker could be counted on to lapse into combinations that caused the ball to avoid the strike zone as if that rectangular cuboid was repellant to horsehide. The only solution in such extremities was to groove the ball down the middle and hope for the best.

Ancker was a strikeout artist on the dusty diamonds of northeast New Jersey, where the Bergen County boys would hack away at anything that approached the plate. There, Ancker’s wildness was practically an asset. If they’re going to be swinging, why not let them swing at a ball in the dirt? But the pros were a cannier bunch, choosing to wait until a pitch came right down the pipe.

The height of the pitcher’s mound probably played a part in Ancker’s wildness. Before 1950, a major league mound could be any height between a flat surface and a 15-inch mountain. Many non-professional ballparks in Ancker’s era had no pitcher’s mound at all. A pitcher accustomed to throwing from one elevation would have difficulty adjusting to a different crest.

Bruno Haas, yet another of Connie Mack’s 1915 kid flingers, had great control when pitching from the unelevated plane at Massachusetts’ Worchester Academy. But when placed on the hill in Shibe Park, which was at least 12 inches high (it measured slightly over 13 inches in 1941), his control vanished. Connie Mack explained the conundrum: ‘The pitching mound fooled him. Twirling on scholastic diamonds, where he stood on a level with the plate, was what he had been accustomed to. When he was lifted into the air a foot or more by the big league mound, it threw off his delivery. We are coaching him out of his trouble rapidly and I believe he will make a valuable player.’

Haas must have learned something. Though he lasted only twelve games with the Athletics, he went on to play parts of twenty-one seasons in the minors. He pitched his last professional game for Class C Fargo-Morehead when he was 55 years old.

The mounds on the semi-pro fields of New Jersey were probably flat, or nearly so, while the North Carolina League mounds had some significant topography. An April 1915 item in the Winston-Salem Twin-City Daily Sentinel, regarding a Twins recruit named Roy Foley, offers this tidbit of insight: ‘Foley says that up in New York, where he hails from, they do not use a pitchers’ mound and for this reason, he has been experiencing trouble in getting the ball down. He expects to master the stunt after a few more trials in the box.’

Postcard showing the Oritani Field Club in Hackensack, New Jersey, circa 1911. It is difficult to glean any definite conclusions, but the pitcher’s mound does not seem to have a significant elevation. The umpire is standing behind the pitcher; they are on a similar plane. The third base side features an enormous swath of foul territory. On the first base side, players lounge beneath a shade tree.

Postcard showing the Oritani Field Club in Hackensack, New Jersey, circa 1911. It is difficult to glean any definite conclusions, but the pitcher’s mound does not seem to have a significant elevation. The umpire is standing behind the pitcher; they are on a similar plane. The third base side features an enormous swath of foul territory. On the first base side, players lounge beneath a shade tree.

Foley’s home base was Fort Slocum, New York, an army post near New Rochelle, just eleven miles as the crow flies from Walter Ancker’s home in Closter. Around Fort Slocum, he was known as Cannonball Foley and averaged sixteen strikeouts per game. In Winston-Salem, he never mastered the ‘stunt’ of pitching from a mound and was released early in the season.

Following Ancker’s disappointing loss to the Twins, the Tourists ended their stay in Winston-Salem with a Saturday afternoon blowout. Harper pitched a complete game, and the Tourists won 13-5.

Corbett made some changes over the weekend. Doc Ferris was sold upstairs to the Columbia Comers of the Class C South Atlantic League. Ferris was a veteran who had won 27 games in 1915. He had so far made three appearances, pitched twenty-two innings, and recorded — by the modern method of reckoning — one win, one loss, and one no-decision. His strength was his control. He had walked only two batters, had not hit any, and had made no wild pitches. The trade-off was that he gave up a lot of hits and runs. Ferris was replaced on the roster by Frank Whitney, the Maryville College boy who had spun a 16-inning loss against the Tourists during the exhibition season.

Corbett played what would later be called Moneyball. With his club chronically short of cash, his most valuable assets were the contracts of his best players. He sold his stars to higher leagues and scavenged their replacements from whatever was below Class D. In this case, Corbett replaced a solid pitcher with one who had won eight games for Class D Newnan in 1915, had pitched well for semi-pro Gastonia, and had looked good in the April exhibition game against the Tourists. Whitney was not a proven commodity like Ferris, but Corbett felt he could hold his own against Class D batters. Corbett was an astute judge of ballplayers. He could use that ability to patch together a quality team with a low payroll.

The Tourists opened a three-game series against the Raleigh Capitals in Oates Park on Monday, May 8. The first encounters were complete-game wins by Lowe (8-1) and Perritt (9-7).

Wednesday was Confederate Memorial Day. May 10 marked the death of Stonewall Jackson in 1863 and the capture of Jefferson Davis in 1865. The former was the harbinger of the Confederacy’s demise; the latter was the final nail in the coffin. All banks in Asheville were closed, and veterans of the Confederate Army enjoyed refreshments in the rooms of the retail merchants association. The United Daughters of the Confederacy presented a program at the Majestic Theatre and decorated soldiers’ graves with flowers and Confederate flags.

That afternoon the newcomer, Whitney, drew the third start of the series. He was hammered, surrendering eight hits, including two doubles and two home runs. Ancker came on in relief in the top of the seventh inning with the Tourists trailing by two runs. He pitched two innings, allowed no hits or runs, struck out four, and walked three. The game was called after eight innings because the Capitals had to catch a train for Charlotte. Final score: 6-8 in favor of the visitors.

The Capitals were replaced in Oates Park by the cellar-dwelling Greensboro Goats. The Tourists led the rumens to the slaughterhouse with shutouts by Harper (13-0) and Perritt (2-0). The Goats regained some dignity in the final game as Lowe lost a close one, 1-2. After completing the series, Asheville stood in third place in the North Carolina League, only two games behind the first-place Charlotte Hornets. The Tourists would have a chance to catch and pass the Hornets the following week. The two teams would meet in Charlotte for a three-game series beginning on Monday.

—-

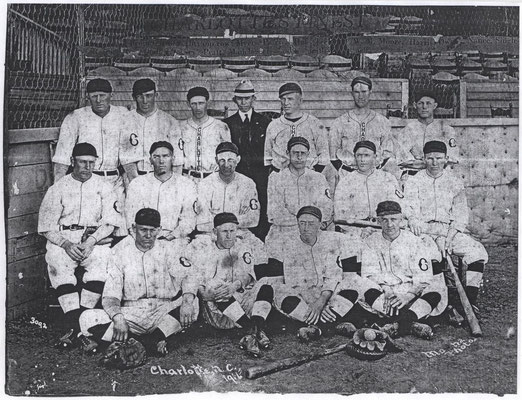

The Charlotte Hornets, 1916. From Queen City Baseball History.

The Charlotte Hornets, 1916. From Queen City Baseball History.

Asheville’s ballplayers filtered into the Southern Railway depot on Sunday morning, May 14, and gathered in the concourse. They wore their best clothes, but the coats and hats could not conceal the underlying coarseness. These were tough men, drifters who made their living playing baseball for small money, on scruffy fields fronted by wooden grandstands, for teams that were perpetually on the verge of bankruptcy.

There were twelve men in the group: Walter Ancker (pitcher), Dallas ‘Rabbit’ Bradshaw (second base), Earl Bitting (third base), Jack Corbett (shortstop), Guy ‘Rebel’ Dunning (right field, left field), Brooks Ellison (catcher), George ‘Doc’ Fenton (center field), Jack Harper (pitcher), Jimmy Hickman (center field, left field), Earle Mack (right field, first base), Olin Perritt (pitcher), and Frank ‘Lefty’ Whitney (pitcher). Two players would remain in Asheville. Ernie Burke (first base) was nursing a sore ankle, and George ‘Doc’ Lowe (pitcher) was resting up from yesterday’s complete-game shutout against the Goats.

Ancker, an electrician, was the only tradesman on the team. The others worked in the off-season as farmers or laborers, or in their family’s business. Only Earle Mack came from a prosperous family. Dunning’s father ran a store in Alabama. Bradshaw’s father sold insurance in Illinois. Hickman’s father was a traveling salesman in Tennessee. Ellison’s father traded cattle in Georgia. Harper’s father worked as a locomotive engineer in West Virginia.

A clot of white-whiskered men had gathered in another corner of the concourse. They were Confederate veterans waiting for the west-bound train that would carry them to Birmingham for the annual gathering of their former army. Each year, death and senility thinned the ranks.

Southern Railway No. 42 pulled into the station just before 7 AM and began to disgorge a very grumpy group of travelers. These were Southern Baptists arriving for their annual convention that would swell the population of Asheville by more than ten percent. When the last adherent had cleared the platform, the Tourists began to board the train bound for Spartanburg, Columbia, and Charleston. The team had an entourage. President Jenkins, some team directors, and assorted family members were tagging along. The morning air was in the low 60’s, but many of the ladies were ‘rushing the season’ by wearing their flouncy summer dresses.

Ostensibly present to support the team, Jenkins’ party was traveling to Charlotte to join in the May 20 Gala that was already taking the city in its grasp. The festival celebrated the signing of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, a document dated May 20, 1775, in which Mecklenburg County declared itself independent of Great Britain. Since it pre-dated the Continental Congress’s Declaration of Independence by over a year, the Mecklenburg Declaration was said to be the Original Declaration, with Thomas Jefferson and his lot being mere copycats.

The signers of the Mecklenburg Declaration failed to tell anyone, including King George III, about their newfound freedom; the document’s existence did not come to light until forty-five years later. Today most scholars doubt the Declaration’s authenticity. But Mecklenburg Declaration Day was a significant event in 1916. President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson, accompanied by the Marine Band, were the featured guests.

The conductor signaled the engineer that all were aboard, and the cars lurched forward. The train turned onto the tracks that led southeast through the fertile French Broad Basin, and Ancker watched the farms passing on both sides of the train. He recognized corn and potatoes, the grains he could never tell apart. Ancker wasn’t a farmer like Frank Whitney, but he knew that the crops were struggling. A serious drought was smothering Buncombe County. There was talk around Asheville of plowing under the oats and planting soybeans. The drought meant less grass in the parks and more dust in the ballplayers’ eyes. When a runner slid into a base — or slud as the southern boys said – he kicked up a blizzard of sand.

The train entered the mountains beyond Henderson, snaking through the gorges between the blue-hazed peaks and ridges, then descended into the flatlands of South Carolina.

The cars eased into Spartanburg at 10:30 AM, where the travelers disembarked to await the No. 12 train from Atlanta that would carry them to Gastonia. There were easier, faster ways to get from Asheville to Charlotte. But President Jenkins wanted to show his largesse by putting the team up for the night in the Armington Hotel and treating them to a fine dinner. The money might be better spent in shoring up the leaning fences of Oates Park, but no ballplayer would kick at the chance for a good meal and a clean bed.

They had a few hours to kill, so the Tourists split up to pursue their fancies. A few headed off in search of a church service. A couple produced their gloves and started tossing a ball around. Corbett hot-footed it to the Western Union office. There was always a clump of loafers hanging around the telegraph terminus in every small southern town. They might have a line on a local semi-pro star, or maybe a high school player who knew which end of the bat to hold. President Jenkins and his followers, seeking Sunday dinner, boarded a streetcar bound for the brand-new Hotel Cleveland. Ancker piled into the car with the players whose priority was determined by hunger.

In the hotel restaurant, the directors and the players sat at tables separated by a wide expanse of carpeted socio-economic real estate. A player slipped a flask from inside his coat and stealthily passed it around.

Ancker perused a newspaper. The cavalry was still chasing Pancho Villa. Each day, the papers reported that the bandit had been cornered. But in the next edition, Villa would turn up somewhere else. The big news was the Army Bill. The House and Senate had agreed to fund a standing army of 206,000 regulars that could be expanded to 254,000 in an emergency, backed by a national guard of 425,000 men. The players joked about who would be left to play baseball if they all ended up in the army.

In Europe, the Germans were attacking both the French at Verdun and the British along the Somme, while the Russians and the Turks were going at it in Armenia. Ancker had occasionally overheard a teammate mention ‘The Hun.’ It made him uneasy. He didn’t share that his father, and his mother’s parents, had been born in Germany.

Everyone trooped back to the depot around 3 PM, and boarded No. 12. Two hours later, they disgorged into the familiar environ of Gastonia, where the ball field featured dunes of dust and an inviting gap in the center field fence. It had been a long trip, and the travelers were glad that the Armington Hotel was just across West Airline Street from the Southern Railway passenger depot.

Over dinner that night, with President Jenkins playing the generous host, the players recalled the banquet that had been thrown in their honor the previous month and ticked off the menu items that had borrowed their names. The pitchers had been represented by Ancker Salad, Queen Lowe Olives, Perritt Cherry Pie, Harper Brew, and Ferris Cocoa. Someone suggested retroactively adding Whitney to the menu and, after considerable discussion, the players decided that the Alabama farm boy should be honored with Whitney Cornpone.

A topic of debate that was unvoiced, at least within earshot of Ancker, was Who’s gonna get cut? The rules of the North Carolina League and the National Association of Professional Base Ball Leagues allowed clubs to carry 22 players for the first 20 days of the season. But on the twentieth day, the roster had to be axed to 13 men. Corbett was carrying 14; someone had to go, and they had to go before Tuesday.

Some players were untouchable: Corbett, of course, and Mack, Hickman, Dunning, Bitting, Bradshaw, and Perritt. Ellison was the only true catcher, but Perritt and Mack had some experience behind the bat. Burke was injured, but he was a good hitter when healthy. A rumor was going around that Fenton’s contract had been sold, but Corbett denied its veracity.

The cut would probably be one of the pitchers, which meant either Whitney or Ancker. The surreptitiously-bet money was on Ancker. He was bringing up the cow’s tail of the rotation, having made only one start, the complete game against Winston-Salem that he blew in the eighth inning. Even counting his two relief appearances, Ancker had pitched just 15 innings. Perritt had 32, Harper had 35, and Lowe had pitched 37.

Whitney looked bad in his one start. But Whitney had been handpicked by Corbett just a week earlier, plucked from the depths of alleged academia. Everyone knew Corbett would give him at least one more start to prove himself. Ancker, on the other hand… Well, Corbett didn’t seem to like Ancker. There was a lack of respect, an impatience that bled into intolerance. Maybe the black-haired Corbett didn’t like Ancker’s head of reddish-brown hair. Or maybe he thought Ancker was just the big dumb guy.

In his 15 innings, Ancker had walked 12 batters and hit two, a total of 14 free passes or 0.93 free passes per inning. His nearest competitor was Jack Harper, whose 0.46 free passes per inning was less than half of Ancker’s. Lowe had the best ratio with 0.21, and Perritt was not far behind with 0.28.

The statistics available in the box scores fail to reveal other indicators of control: the pitch count and the number of balls vs. strikes. Ancker was probably throwing a large number of pitches, probably facing a lot of full counts. Nor do the numbers show the degree to which Ancker was missing the strike zone. In a box score, four pitches just off the outside corner are identical to four balls smothered in the dirt by the catcher. When a pitcher is continually described as wild, he’s likely missing the mark by a wide margin.

—-

The players enjoyed a late breakfast Monday morning, then made the obligatory visit to the Armington’s veranda where, on a clear day, Kings Mountain was visible to the south. Today, though, the view was obscured by clouds drifting in from the Gulf Coast that offered the opportunity for a dust-dampening evening shower. After recovering their bags from the lobby, they walked three blocks east down Airline to the Piedmont and Northern railway station.

The P&N ran an all-electric service with an ‘inter-urban’ passenger train departing for Charlotte every other hour. The players hauled their gear into a car at 11 AM. Sixty minutes later, they arrived at the P&N passenger depot at the corner of Mint and West Fourth. A half-mile streetcar ride southwest down Mint brought them to within a block of Wearn Field where the Tourists would meet the Hornets at 4 PM.

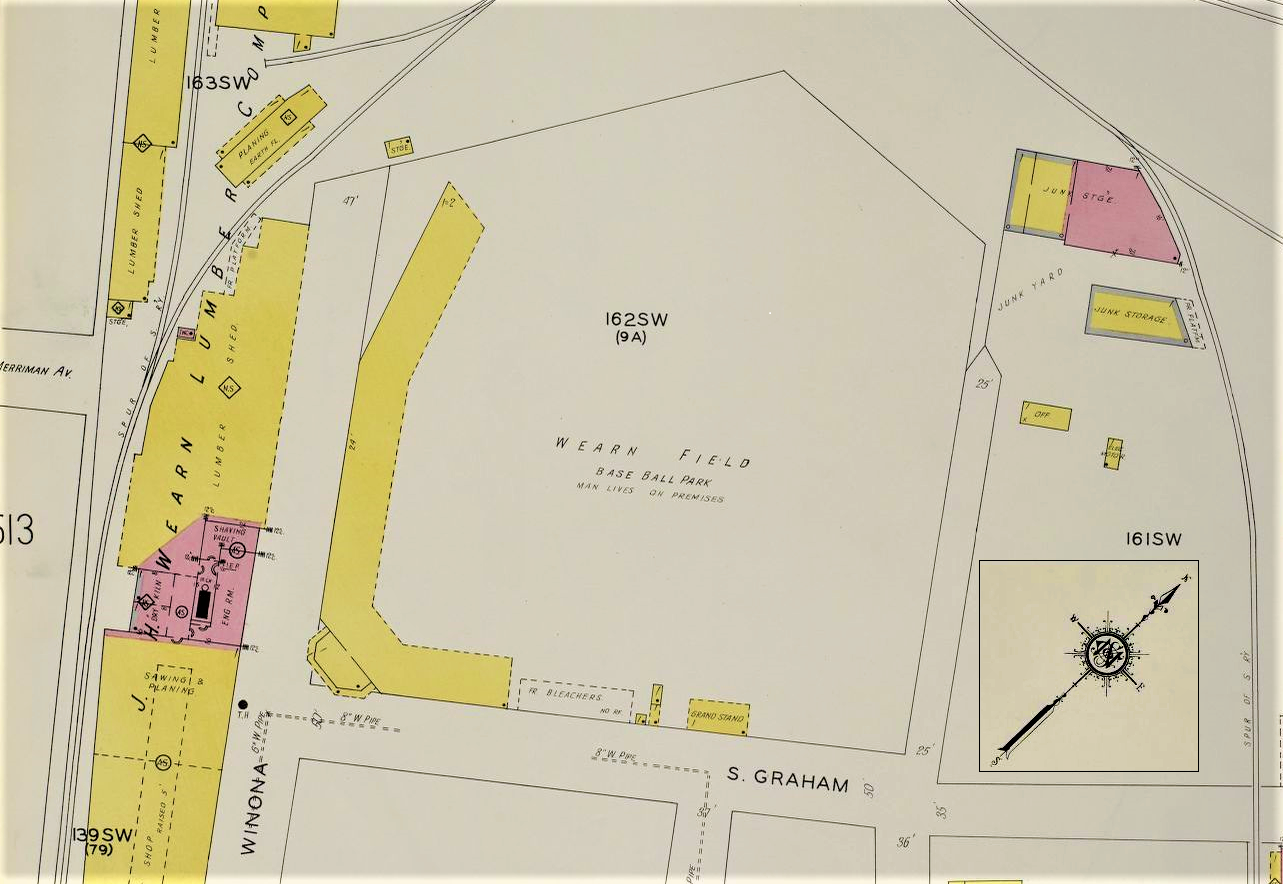

Wearn Field in Charlotte, North Carolina. Home plate was at the corner of South Graham and Winona. The right field corner was at South Graham and Commerce. The small print below ‘Wearn Field Base Ball Park’ reads ‘Man lives on premises.’ Note that the top of the map is northwest; the bottom of the map is southeast. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, 1929, Volume 2, Sheet 512. From the Library of Congress.

Wearn Field in Charlotte, North Carolina. Home plate was at the corner of South Graham and Winona. The right field corner was at South Graham and Commerce. The small print below ‘Wearn Field Base Ball Park’ reads ‘Man lives on premises.’ Note that the top of the map is northwest; the bottom of the map is southeast. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, 1929, Volume 2, Sheet 512. From the Library of Congress.

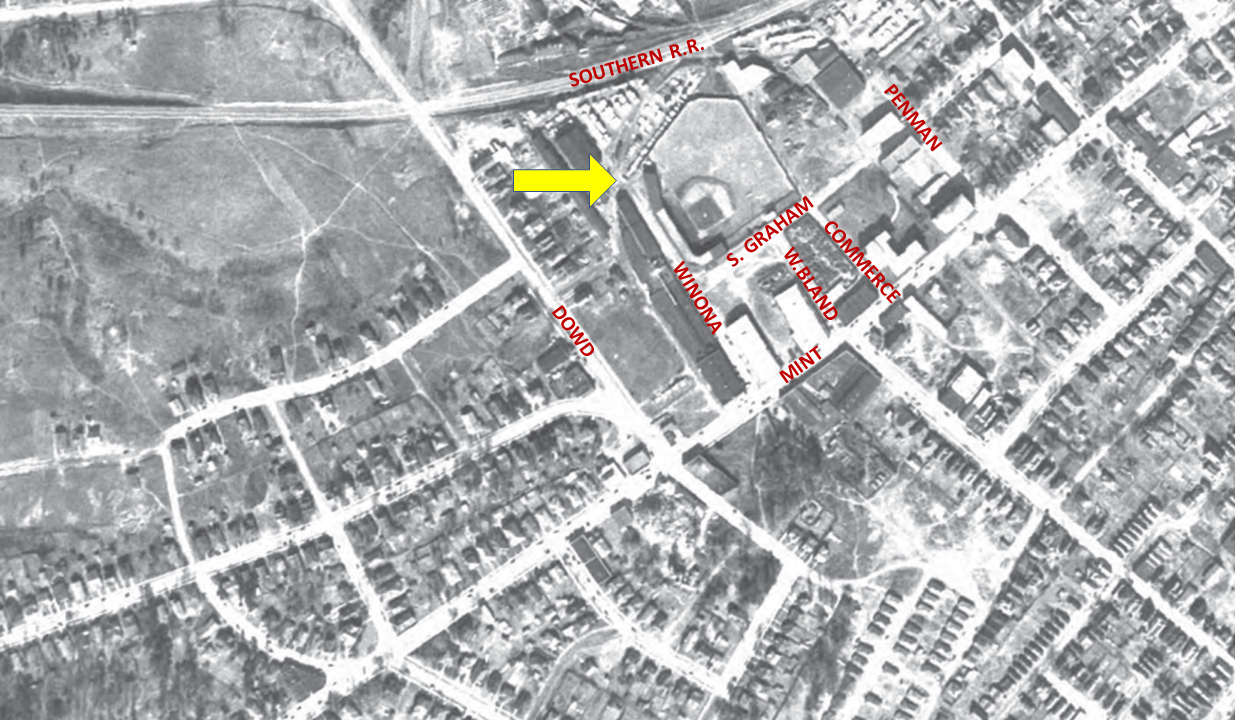

Aerial photo showing Wearn Field (yellow arrow), 1938. The site is now used to store construction equipment. From Urban Planet.

Aerial photo showing Wearn Field (yellow arrow), 1938. The site is now used to store construction equipment. From Urban Planet.

The players had predicted that Corbett would give Whitney at least one more start to prove his worth, and that start came Monday afternoon before a crowd of 900 fans. The game was umpired by Ed Lauzon, who had incurred Corbett’s wrath the previous September, earning the manager a fine and suspension.

The game began well for Asheville. Leadoff hitter Dallas Bradshaw hit one into the dirt in front of home plate but reached first on a throwing error by Charlotte’s catcher. Corbett singled, and both runners advanced on a sacrifice fly by left fielder Jimmy Hickman. Then third baseman and cleanup hitter Earl Bitting sent the ball over the left-center fence for a three-run homer.

Bitting began the 1915 season playing for the Charleston Sea Gulls of the Class C South Atlantic League. After the league completed its short season at the end of July, he moved to Lenoir of the semi-pro Western North Carolina League. As it happened, Bitting had also made commitments to play for two other WNCL teams, Statesville and Gastonia.

When Statesville threatened to pull out of the league if Bitting was allowed to play, the league president ruled that he could remain on Lenoir’s roster, but he would have to ride the bench whenever Lenoir met Statesville. After the regular season ended, Bitting joined the Gastonia squad, where Frank Whitney was a teammate, for the league championship series. Corbett acquired Bitting’s contract in late 1915.

Bitting’s blast would be all for the Tourists’ offense, but it was all Whitney needed. The lefthander was, in the words of the Citizen-Times, ‘wild as a hare.’ But he pitched well when it counted and benefitted from excellent play behind him.

The clouds were spitting rain throughout the game. The drizzle turned into a full-on downpour in the fourth inning, and umpire Lauzon called a 30-minute halt. The rain ceased, and the drought-starved sand dried out quickly.

The Hornets loaded the bases in the fifth inning, with one out and cleanup hitter Andy Anderson at the plate. Anderson ripped a liner down the third base line for what looked like a certain triple. But Bitting instinctively grabbed the ball with his bare hand and stepped on the base to double the runner.

Bitting’s double play seemingly occurred outside the normal time-space continuum. The Charlotte News reported that the play took place in the fifth inning with one out. The Charlotte Observer agreed that it happened in the fifth but was silent on the number of outs. The Asheville Citizen-Times claimed it was in the second inning with no outs, and the Durham Morning Herald placed it in the fourth inning with no outs. The Raleigh paper acknowledged the play but offered no details, and the Winston-Salem paper avoided the issue entirely. The out-of-town reporters probably received their information second-hand via telegraph, or by telephone from a stringer. It is also likely that any reporters on the scene were nipping from a flask.

Whitney was clinging to a 3-0 lead in the bottom of the ninth when the Hornets loaded the bases with one out, but a fly and a grounder ended the game. Whitney gave up seven hits and walked seven; the Hornets left 14 men on base. Corbett was willing to let Whitney work out of trouble, and he earned his manager’s trust by pitching a complete-game shutout.

After the game, the Shriners’ Arab Patrol drill team took over Wearn Field to practice. As the colorfully-clothed gentlemen marched across the outfield in close order, Corbett announced that he had released Jack Harper to make the 13-player roster limit. It was an odd choice. Harper had a 3-1 record, the best on the staff, and led the team in strikeouts with 18. There was speculation that Corbett was up to something.

—-

Lord, let me live like a Regular Man,

With Regular friends and true.

Let me play the game on a regular plan,

And play it all the way through.

Let me win or lose with a regular smile

And never be known to whine,

For that is a Regular Fellow’s style

And I want to make it mine!

— From ‘The Regular Man’ by Benton Braley, printed in the Gastonia Gazette, May 16, 1916

Tuesday, May 16, opened with the Tourists just a single game behind the Hornets. A win today and the pennant race would be knotted, with Wednesday’s game presenting a chance for Asheville to take the lead.

Before wandering to Wearn Field, the players enjoyed a bit of the holiday atmosphere that pervaded Charlotte. The Metropolitan Carnival had opened on Monday night; First Street between South Tryon and Church became a village of tents. The streets were alive with peddlers selling balloons and pennants, and farmers hawking eggs, produce, chickens, and even cows. The visitors included a fair number of the unsavory types who always show up for a party. Newspapers reminded citizens to keep their doors and windows locked, hide the family silver, and carry no unnecessary cash when leaving home.

A featured attraction at the carnival was Hazel the Mummy, the embalmed corpse of Hazel Farris. Ms. Farris’s remains had been displayed in various locations in the South for almost a decade and would continue to be an attraction for another half-century.

The Tate-Brown Company, a large department store on South Tryon, invited out-of-town guests to stop by and enjoy free access to ice water, writing supplies, a telephone, and a restroom. While in the store, any man who was still sporting a cloth cap or bowler could explore Tate-Brown’s selection of the 1916 model straw hats — ‘thousands of them’ — or purchase a new knee-length Union suit (starting at just one dollar).

Corbett’s choice for the starting pitcher in Tuesday’s critical game came down to Ancker or Perritt. Whitney had pitched a complete game the previous day, Lowe was in Asheville, and Harper was supposedly released. He was still there; he stayed with the team Monday night and accompanied them to Wearn Field on Tuesday. Corbett handed the ball to Ancker.

The game was played in a strong wind, under dark clouds that were leaking rain, before 950 fans. The men who had not exchanged their bowler for a boater were sweating in the 80-degree humidity.