The Semi-Pro: The Baseball Life of Walter Ancker (Chapter One)

Chapter 1:

Chapter 1:

The Kid Flinger

Walter Ancker, the star pitcher of the Tenafly, N.J., team of the North Jersey league, is the latest kid flinger to be caught in Cornelius McGillicuddy’s dragnet. Ancker, who is a Closter, N.J., lad, yesterday signed a two-year contract with Mack, and will report to the Mackian troops on Sept. 1. Ancker is a big right-hander, 6 feet 1 inch tall, weighing 180 pounds. He is just old enough to vote. He has been pitching phenomenal ball for Tenafly this season, having won 15 games and lost but 2. He has pitched two no-hit games, and last Saturday he defeated Englewood with one hit and struck out 14 men. Several major league clubs were after the youth, but Dave Driscoll, one of Mack’s scouts, got Ancker for the Athletics. — Asbury Park Press, August 18, 1915

The excited — and today nearly indecipherable — prose penned by an anonymous New Jersey sportswriter announced that Walter Ancker, a young pitcher — a kid flinger — with the Tenafly Baseball Club, a semi-pro team in Bergen County, New Jersey, had been signed by the Philadelphia Athletics of the American League. The Athletics were managed and co-owned by Cornelius McGilllicudy, better known as Connie Mack. He had been signing a lot of untried pitchers that season, and Walter Ancker was his latest recruit. Ancker was 22 years old. And he was jumping directly from semi-pro ball to the majors, by-passing the usual years of thankless toil in the Purgatory of the minor leagues.

Connie Mack was one-third of the way into an astonishing 50-season reign on the top step of the Philadelphia dugout and had already won six American League pennants and three World Series. The Athletics (later of Kansas City and currently of Oakland, having completed their transcontinental crossing in 1968) won the American League pennant in 1913 — there were eight teams in the league, and no divisions — then defeated the New York Giants of the National League in the World Series. In 1914 they repeated as American League champs but lost to the ‘Miracle’ Boston Braves in the Series.

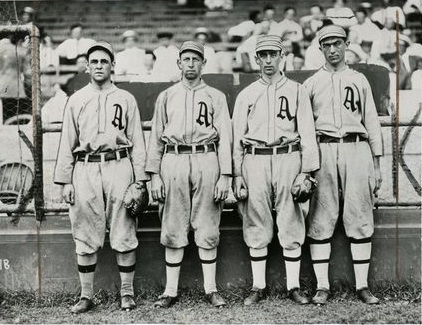

The Athletics of 1913 and 1914 included five future Hall of Famers: pitchers Chief Bender, Herb Pennock, and Eddie Plank, third baseman Frank ‘Home Run’ Baker (he led the American League with a whopping 12 home runs in 1913 and 9 in 1914), and second baseman Eddie Collins. Baker, Collins, shortstop Jack Barry, and first baseman Stuffy McInnis were known as the $100,000 Infield, one of the best and highest paid infields of the time.

Philadelphia’s “$100,000 Infield” of 1910-1914. Left to right: Stuffy McInnis (1b), Eddie Collins (2b), Jack Barry (ss), and Frank Baker (3b). From MadFriars.

Philadelphia’s “$100,000 Infield” of 1910-1914. Left to right: Stuffy McInnis (1b), Eddie Collins (2b), Jack Barry (ss), and Frank Baker (3b). From MadFriars.

But the 1915 Athletics were cut from a very different bolt of flannel. An upstart circuit, the Federal League, had appeared on the scene offering its players better pay and freedom from the reserve clause that kept players’ salaries artificially suppressed until the mid-1970’s. A bidding war erupted and the salaries of star players skyrocketed. But Connie Mack refused to play along. Instead, he dismantled his championship team in an epic fire sale, sending his stars to other teams and replacing his veteran pitchers with a string of young, low-paid flingers like Walter Ancker. The result: Mack’s Athletics were transformed from the best team in the league to the worst. They turned in a 43-109 (.283) record in 1915. The Athletics were even worse the following season: 36-117 (.235). It is still the lowest winning percentage for any post-1900 major league team.

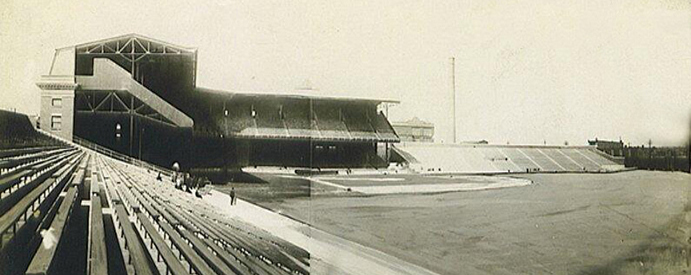

Ancker made his debut with these struggling Athletics on Friday, September 3, 1915, pitching five innings of relief against the Boston Red Sox. It was the Athletics’ 121st game of a 154-game season. That morning the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer was dominated by a photograph of the sinking of the Arabic, a White Star ocean liner that had been torpedoed by a German U-boat resulting in the loss of 44 lives. The game was played in Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, only six seasons old, the first baseball stadium to be constructed of steel and concrete. Home plate umpire Dick Nallin yelled Play ball! at 3:30PM.

The day did not go well for the Athletics. Ancker entered the game in the top of the fifth inning, replacing starter Tom Sheehan, with the Athletics trailing 0-9. Sheehan was another of Mack’s kid flingers. He was a year younger than Ancker and had pitched his first game for the Athletics back in July. Until that day he had performed reasonably well. He went on to a six-year career as a major league player, then worked as a coach, minor league manager, and scout. In 1960 he became, at age 66, the major leagues’ oldest rookie manager when he took over in mid-season as skipper of the San Francisco Giants. He was a terrible manager; as Willie Mays cryptically described Sheehan, ‘He was in uniform in body only.’ When Sheehan joined the Athletics in 1915 he was paid $300 a month; Ancker was probably paid a similar amount.

Shibe Park circa 1912-13. From Bill Davis, Paris LF.

Shibe Park circa 1912-13. From Bill Davis, Paris LF.

Walter Ancker walked to the mound around 4:15PM. The grainy black-and-white photographs and jerky newsreels that illuminate the era have led us to believe that every game was played on a muddy, clod-strewn field under overcast skies. But the grass onto which Walter Ancker stepped was green. It was a beautiful late-summer day, just a few clouds in the blue sky, with the temperature around 77 degrees. A perfect afternoon for baseball. There were a little over two hours of daylight left, but the game would end long before sundown. Pitchers worked rapidly — though sometimes with an elaborate, windmilling windup — and batters were expected to stand in the box and take their cuts without the endless adjusting of stance and equipment.

When Ancker took the mound for the first time he was, in the words of a visiting writer for the Boston Globe, ‘blushing like a school girl.’ Completing his warm-up tosses, Ancker paused and took in the moment. Here he was, twenty-two years old, a deep fly ball’s distance from Tenafly, on the mound for last season’s American League pennant winner. The team was terrible and he was the low man on a poor pitching staff. But he was in the major leagues.

Ancker glanced up at the stands of Shibe Park, which were practically empty. The Red Sox were the best team in baseball and the Athletics were the worst. Only a few hundred fans had turned out to witness another late-season massacre, and the ones who had not already departed were there to gamble. They would bet on anything: the game’s final score, the results of an inning, even the outcome of a single at-bat. There were no women in the stands, and nearly all of the men wore the flat-topped straw hats known as boaters.

With the seats nearly deserted, most of the noise was coming from the Boston dugout. The Red Sox were riding Ancker unmercifully, trying to rattle the youngster. They had been at it all day and Nallin, the umpire, had already ejected two of the Sox for bench jockeying. Ancker didn’t look into the Boston dugout, but if he had he would have seen Babe Ruth. Ruth was completing his first full season with the Red Sox, having spent part of the previous year in the minors. Just 20 years old, he was an excellent pitcher and an above average hitter. But in 1915 The House That Ruth Built was not even a blueprint. Ruth had a big, wild swing, and when he had been sent to the plate as a pinch-hitter in the previous inning, he struck out.

Anker glanced toward the Philadelphia dugout and saw a lanky man in a fine suit. Connie Mack, the Tall Tactician, the man who had just thrown Ancker to the lions, eschewed the player’s uniform adopted by most managers, preferring to dress as a gentleman. He was known for hiring intelligent players, like Columbia grad Eddie Collins, then stepping back and allowing them to play intelligently. He was ready to take his first long look at his latest recruit.

Rubbing the well-worn ball, Ancker turned his back to the plate and nodded to his infielders. Crouched in the gap between first and second base was Napoleon Lajoie, who had been purchased from Cleveland in the off-season. Just two days away from his 41st birthday and playing out the next-to-last of his twenty-one seasons, ‘Larry’ Lajoie was the closest thing Connie Mack had to a star player. Lajoie had led the league in batting five times and four times collected the most hits. The previous year he had become only the third major-league player to amass 3000 hits. He was an elegant fielder known for an effortless, almost disinterested style that yielded the league lead in putouts five times and in assists three times. He would be the first second baseman elected to the Hall of Fame.

Walter Ancker knew that his second baseman was one of the game’s greatest players, and he knew that Lajoie’s career was nearing its end. Perhaps he recalled the words of St. Louis sportswriter Billy Murphy, written a few months before when the Athletics played the Browns: There you have Napoleon Lajoie — a monolith of what was once the greatest pastime the world has ever known. He is a relic of the days when giants ran rampant on the diamond. How long will it be before he, too, will fall like a withered leaf, into the stream of Time?

Ancker faced the plate, toed the rubber, and prepared to deliver the ball to catcher Jack Lapp. But first there was the matter of just who this young man was. Shouting through his megaphone, the Shibe Park announcer asked Lapp for the name of his new pitcher. Emerging from his crouch and removing his mask, Lapp turned to the announcer and yelled that he couldn’t remember the kid’s name. The Athletics used twenty-six pitchers in 1915, and Lapp had given up trying to tell them apart. The announcer’s assistant trotted out to the mound and returned with Ancker’s identity. He may not have caught the spelling, though. The writer for the local Public Ledger, describing the day’s game in the evening edition, spelled it Anker.

Finally, Walter Ancker made his first pitch as a major leaguer, to Red Sox starting pitcher Ernie Shore. Ancker retired the first batter he faced, as Shore grounded to Lajoie at second.

The next batter was Boston’s leadoff hitter, right fielder and future Hall of Famer Harry Hooper. Hooper, left fielder Duffy Lewis, and center fielder Tris Speaker, also destined for the Hall of Fame, were the Golden Outfield, the best defensive outfield of their day. ‘They were the greatest defensive outfield I ever saw,’ wrote Grantland Rice. ‘They were smart and fast. They covered every square inch of the park. They could move into another country if the ball happened to fall there.’

The three outfielders were separated by more than just the grass of Fenway Park. Speaker was a Protestant, while Lewis and Hooper were Catholics. Feelings between Protestants and Catholics were especially sharp in the 1900s, as the Protestants accused their fellow Judeo-Christians of moving into their neighborhoods and ruining the property values. On the Red Sox the Protestant Faction, led by Speaker, and the Catholic Faction, led by Lewis, were enmeshed in a daily Religious War. Lewis once threatened to kill Speaker, and Speaker went an entire season without talking to either Lewis or Hooper. The Golden Outfield’s separation became permanent when Speaker was traded to Cleveland after the 1915 season.

Harry Hooper welcomed Ancker to the big leagues by whacking a double to left. Ancker responded by throwing a wild pitch to Boston shortstop Hal Janvrin, allowing Hooper to take third. Janvrin waited out a walk and immediately stole second. Tris Speaker, batting third in the order, put down a bunt. Ancker fielded the ball and threw to first, getting the out on Speaker as Hooper scored and Janvrin moved to third base. Ancker then plunked the next two batters, first baseman Dick Hoblitzel and left fielder Lewis, to load the bases. But Boston third baseman Larry Gardner sent another grounder to the reliable Lajoie to end the inning.

The line score for the fifth inning: one run on one hit, no errors, three men left on base. Not a bad result considering what a sorry show it was: a double, a wild pitch, a walk, and two hit batters. But Ancker calmed down after that. Over the next four innings he gave up no runs on five hits, walked one, and didn’t hit anyone. He got one strikeout, on Boston second baseman Jack Barry, formerly a member of Philadelphia’s $100,000 Infield, who would finish the year with a .244 average. The game ended with a 2-10 Boston win after Philadelphia scored a pair of late-inning runs off reliever Vean Gregg.

Ancker’s opening performance received mixed reviews. ‘Considering this was his first tryout in fast company,’ the sympathetic Hackensack Record reported, ‘his showing was a good one, and the Bergen County fans are rooting for him to make good.’ But the sportswriter preceded his faint praise with a note of caution: ‘He was a trifle wild, giving two bases on balls, hitting two batsmen and making a wild pitch.’

And thus was thrown the seed of Ancker’s soon-to-arrive major league demise: control, or lack of it. He could no longer rely on a parade of free-swinging semi-pro players who were happy to hack away at any pitch that approached the plate. In semi-pro, Walter was known as a strikeout pitcher. But in his first major league appearance he struck out only one batter, and that was one of Boston’s weaker hitters. Now he would have to hit the corners or, failing that, at least hit the catcher’s mitt and not the batter or the backstop.

—–

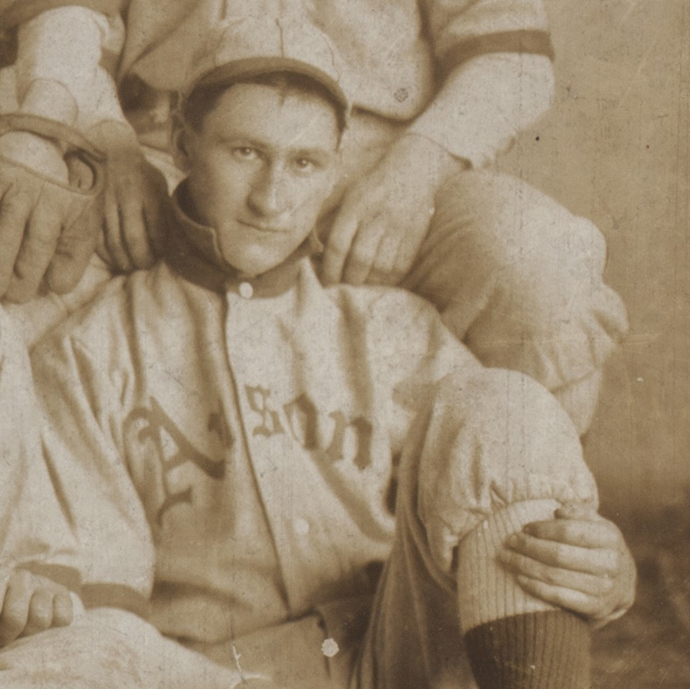

The four Ancker brothers. Walter is probably the tall one on the left.

The four Ancker brothers. Walter is probably the tall one on the left.

Walter Ancker was born April 10, 1893 in Manhattan. He was not given a middle name. His father, Edwin Ancker, was a veterinary surgeon — a horse doctor, in the lingo of the time.

Edwin Ancker was born in Germany and came to the US in 1885 when he was 25. Four years later he married 20-year-old Auguste Goetzger. They had four sons: Edwin Jr., William, Walter, and Raymond. The 1900 census shows the family living in an apartment on West 30th Street, along with one of Edwin’s German-born cousins. By 1905 they had moved to Closter, New Jersey, in Bergen County. Edwin died in 1911.

Walter was an electrician by trade and gave that as his occupation in the 1915 New Jersey state census, the year he pitched for the Athletics, as well as in the Federal censuses of 1920 and 1930.

Seneca Falls semi-pro team, 1920. Walter Ancker is the tall one in the back row, third from right. Photo from Seneca Falls Historical Society.

Seneca Falls semi-pro team, 1920. Walter Ancker is the tall one in the back row, third from right. Photo from Seneca Falls Historical Society.

At six-foot-one Walter was considered tall, and most descriptions of him involve the word big. During a 1915 semi-pro game in Hackensack, he collided with a smaller player named Abbenseth resulting in ‘the big Closterian spinning little Abbie like a top.’ He weighed 180 pounds when he signed with the Athletics. A year later he was up to 190 pounds. In 1923 he weighed 200 pounds and was described as being of ‘gigantic stature.’

Ancker was a good-looking guy. ‘He looks like a physical culture model, one writer enthused. Another noted that he was ‘a hero in the eyes of young women admirers.’ He probably had reddish-brown hair. On his WWI and WWII draft registrations his hair (and eyes) were noted as being brown. But in 1927 a writer called him ‘the red-haired veteran’ and ‘the big red-head.’ In the Hackensack Record he was usually referred to as ‘Red’ as in big ‘Red’ Ancker.

According to most baseball references, Walter Ancker had two nicknames, ‘Liver’ and ‘Gee.’ I could find no contemporary uses of ‘Liver’ in reference to Ancker, and only one of ‘Gee.’ Perhaps ‘Gee’ was derived from the commands used to steer a horse or mule. Gee turns the animal to the right, Haw to the left. ‘Gee’ may have been an indicator that Ancker was the size of a horse, and a right-handed pitcher.

Walter Ancker was definitely born in 1893 as shown in the New York City birth records, the Federal census of 1900, and the New Jersey censuses of 1905 and 1915. But he managed to throw some confusion onto the issue by occasionally giving his birth year as 1894.

The excited reporter who described Walter as just old enough to vote in 1915, when Ancker was 22, may have been told that Ancker was 21 (the voting age in 1915). When Ancker registered for the draft in May 1917, when he was 24 years old, he added one year to his birth date — reporting it as 1894 instead of 1893 — but subtracted two years from his age, writing it as 22 (and implying a birth year of 1875). A 1927 article in the Hackensack record, published when Walter was 34-years-old, gave his age as 33. When Walter registered for the WWII draft on April 26, 1942, he recorded the correct birth year (1893) but the wrong age (48 instead of 49). And in 1948, when he sent a card to a fan who had asked for an autograph, he again wrote in a birth year of 1894.

It is possible that Walter Ancker did not know his actual birth year or had trouble remembering it. Maybe he tried to shave a few years from his age to make himself more attractive to prospective teams. He was definitely bad at math.

Ancker played on many different semi-pro teams, sometimes on more than one team in a season, suggesting that he didn’t get along with managers. But semi-pro pitchers of that era were nomads. They were better paid than the position players, were often paid on a per-game basis, and pitched for the team that offered them the most money. A 1928 article in the Paterson News had this to say about Walter Ancker: ‘Although a hard man to please at times, he is a fighter all the way and as such is highly regarded by the fans.’

In 1931, when he was attending a game in Hackensack as a fan, Ancker came out of the stands to put his two cents into a dispute about whether a runner had scored on a dead ball. Addressing an umpire named Livingstone, Walter is quoted as saying, ‘You’re a rotten umpire, Livingstone — absolutely the dumbest guy I’ve ever seen.’ His language was undoubtedly cleaned up for public consumption.

While a pile of sports page clippings may reveal little about the man, the columns allow an educated guess about Walter Ancker the pitcher. One writer said that he was ‘a “smoke ball” artist, with an overhand sweep that sends a ball across the plate with a speed that gives it the appearance of a pea.’ Another said Ancker had ‘a wealth of smoke and an assortment of curves.’ Yet another described him as a ‘youthful dropball artist’ with ‘a world of stuff.’ When Ancker was a mere 34 years old, a writer said, ‘The old boy has always been a good mechanical pitcher.’ The following year a writer noted that ‘old Walt Ancker… had his speed ball and hook working to perfection.’ And a year after that it was said that Walter threw ‘curves and hooks that had the boys guessing years ago.’

These descriptions suggest a big guy with a smooth, overhand delivery that preserved Ancker’s arm and kept him on the mound until he had advanced from youthful to old. Think Nolan Ryan.

By varying the grip and release, the overhand pitch can be a straight fastball, a down-breaking 12-6 curveball, or a sinking changeup (a dropball). By lowering his arm to three-quarters, Ancker could have delivered a curve that left his hand aimed straight for a right-handed batter’s head before breaking down and away across the plate. The typical advice one gets when facing a curveball pitcher is to wait for it to break before swinging. The report of a 1927 game in Hackensack noted that a batter ‘made the h.p. [hit by pitch] column… by waiting too long for one of “Red” Ancker’s curves to curve.’

Ancker may have occasionally dropped down to the sidearm delivery that Walter Johnson used, which made the curveball appear to be coming out of the third base bag before breaking laterally across the strike zone. It’s a difficult pitch to master, and often results in a right-handed batter being plunked in the back. And he probably threw in an occasional screwball, the fadeaway pitch made popular by Christie Mathewson, that broke in to a right-handed batter and tailed away from a left-hander.

The overall picture we have of Ancker is of a classic power pitcher — fastball, curveball, changeup — with a few tricks tossed in that he had learned to throw but not control.

The Bergen County batters would have no doubt flailed away at Ancker’s offerings. But the major leaguers would have been content to take all the way and wait for Ancker to throw a strike. And therein lies the difference between a successful major league pitcher and those who never make it beyond the bounds of Bergen County: the good pitchers can throw their breaking stuff for strikes. Lesser pitchers can’t, and Walter Ancker couldn’t.

In the late 1920’s an old Bergen County baseball man claimed that Walter Ancker ‘played his first baseball of any kind in 1914 for Tenafly.’ But it’s doubtful that any player — even a kid flinger — could go from not playing the game at all to pitching in the majors in a span of less than two seasons.

An August 1915 article in the Hackensack Record that announced Ancker’s signing with the Athletics stated that ‘his work in the box has been watched with interest by Bergen County “fans” for several years,’ suggesting that he had been on the semi-pro scene for a while.

There were two Anckers playing for the Hackensack Athletic Club in 1913: W. Ancker and “Buck” Ancker. Both Anckers pitched and played the outfield. W. Ancker was probably Walter. “Buck” Ancker could be any of the Ancker brothers, or any other young man with the last name of Ancker.

In 1914 we find an Ancker pitching for the Englewood Athletic Club early in the season; later in the year an Ancker was pitching for the Hackensack Field Club. On October 4, 1914, he struck out ten batters in four innings. That pitcher was almost certainly Walter Ancker.

We know for certain that Walter Ancker had a tremendous semi-pro season in 1915 before joining the Athletics. By mid-August, Anker had won fifteen games for the Tenafly Baseball Club, including two no-hitters, losing only three.

Early in the season Ancker beat the powerful Oritani Field Club, handing the Indians their first loss of the year. In July he pitched a 15-inning complete game against the Chambers Arrows, with Tenafly winning 4-3. And just prior to being signed by the Athletics he defeated Englewood, one of the better Bergen County teams, giving up just one hit and striking out fourteen.

In his final start for Tenafly before moving up to the majors, Ancker once again defeated Oritani, shutting them out 7-0, giving up only one hit and striking out eleven, while walking five and twice drilling George Schmidt, the Oritani left fielder. ‘Ancker’s benders were unsolvable to the Oritani batters,’ the Hackensack Record reported. ‘At times he showed an inclination at wildness, but the bigger the hole he got in the more air-tight he became.’ In the fourth inning Ancker walked two batters and hit the unlucky Schmidt to load the bases, then recorded three straight outs.

The following day, Schmidt was complaining of a sore back. ‘No wonder,’ the Hackensack Record teased, ‘for those were not “dope” balls by any means that Pitcher Ancker sent into that portion of his body.’

—–

Shibe Park, around 1909. From This Great Game.

Shibe Park, around 1909. From This Great Game.

Walter Ancker made his first major league start on Tuesday, September 7, 1915, pitching against Washington. Unlike his previous outing, when he was called in from the bullpen to mop up the remnants of a previous pitcher’s disaster, this game would be Ancker’s from the get-go.

The Washington baseball club was originally named the Senators, but the team had been renamed the Nationals in 1905. The new name didn’t stick with the public: the fans still called them the Washington Senators. In the sports pages they were known as the ‘Griffs’ after manager Clark Griffith.

The team’s identity crisis has continued into the present day. In 1961 the franchise was relocated to Minneapolis and renamed the Minnesota Twins. They were replaced by a new Washington Senators franchise, which lasted ten years before moving to Arlington, Texas and rebranding itself as the Texas Rangers. In 2005 the Montreal Expos were moved to Washington and renamed the Nationals. Thus, there are currently two major league teams that were formerly the Washington Senators. One of the former Senators was once the Nationals, and today’s Nationals were once the Expos.

The Senators were led by Walter ‘The Big Train’ Johnson, a future Hall of Farmer and possibly the best pitcher in the history of baseball. Johnson was in the ninth of his twenty-one seasons and was on his way to winning 27 games, the best in the American League that year. Fortunately, Ancker would not have to pitch against Johnson, who was due to go against the Yankees the next day in the Polo Grounds. Walter had drawn Bert Gallia, a Texan who would end the season with a 17-11 record. The Athletics had lost seven straight games; Ancker was being thrown into the breach.

It was beautiful day in Philadelphia, 78 degrees and partly cloudy. The newspapers that morning announced that another ocean liner had been torpedoed by a U-boat: the Hesperian went down off the coast of Ireland with the loss of 32 lives and 4000 sacks of mail. The teams were playing a double-header, so the 300 fans who had turned out on a week-day would get their money’s worth — 50 cents for a seat in the pavilion, less in the bleachers — if they stayed around.

Ancker walked to the plate and began his warm-up tosses to catcher Wickey McAvoy just before 1:30PM. Wickey was only 20 years old and had already played parts of three seasons with the Athletics. Walter would have preferred to work with a more experienced catcher like Jack Lapp, someone who knew The Book on Washington’s hitters. But the kid flinger was paired with the kid catcher. After a final fastball smacked into his mitt, McAvoy trotted out to the mound to check their signals one last time. Wickey gave his pitcher a non-ironic Good luck, kid and returned to his position behind the plate.

If Walter Ancker was a dreamer, then this was a moment of fantasy fulfillment: standing on the mound at the center of a big league diamond, holding a baseball in his right hand, ready to deliver his first pitch as a major league starter. It wasn’t exactly Game 7 of the World Series, but it was better than a bumpy field in Bergen County. All he had to do was pitch well. He might not become the next Walter Johnson, but maybe he could become the next Chief Bender.

Bill Nallin, the home plate umpire for Ancker’s first appearance, would again call the balls and strikes. Nallin yelled Gimme a batter! and Washington outfielder Merito Acosta stepped up to the left side of the plate. Acosta was a future inductee into the Hall of Fame: the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame. He was a weak hitter but fast, and used a compact, hunched over stance that was difficult to pitch to. Ancker probably tried his fadeaway pitch, keeping the ball low and away from the left-handed batter. But he wasn’t able to hit the corner of the plate within Acosta’s narrow strike zone, and the Cuban jogged to first with a walk.

Next up: second baseman Eddie Foster. Foster was known for his excellent bat control and was the best hit-and-run batter in the league. With the speedy Acosta at first this could be a dangerous spot. A well-placed single would send the runner to third. With a good jump on a single to right field, Acosta might even score. Ancker nipped the hit-and-run in the bud by drilling Foster, sending him to first and Acosta to second.

Ancker now faced center fielder Clyde Milan. Born in Tennessee, he would die in Florida and be buried in Texas. Known as ‘Deerfoot,’ Milan was another speedster. He stole the most bases in the league in 1912 and 1913. Milan popped up to McAvoy in foul territory and the runners were unable to advance. One down.

With one out and two men on, Washington’s cleanup hitter, third baseman Howie Shanks took his stance in the batter’s box. Just five years before, Shanks had been diagnosed with tuberculosis and given two weeks to live. He recovered and was now completing the fourth of his fourteen major league seasons. Shanks was a big right-hander. When he was beaned by a fastball in 1912, eight men were required to carry him off the field: four to keep his arms and legs from flailing about while the other four did the hauling.

Shanks grounded to Lajoie, today making a rare start at shortstop, who pegged the ball to third base to get the force out on Acosta. But they were unable to turn the double play. Foster was safe at second and Shanks pulled in at first. Two down.

That brought up Washington first baseman Chick Gandil. Gandil had a hard look, like he’d just as soon kill you as give you the time of day. In 1919 he would lead Chicago down the road to Perdition in the Black Sox scandal. But in 1915 he led Washington in runs batted in, a dangerous hitter with two men on. Someone in the Philadelphia dugout yelled Don’t give him anything he can hit. Ancker obliged by walking Gandil — possibly an intentional walk with first base open — to load the bases.

The sixth batter was right fielder Sam Mayer. Like Ancker, Mayer was 22 years old and had played his first game in the majors the previous week. And, like Ancker, he would not return for another season. Mayer was a true utility man. In his eleven appearances with the Senators he played left field, right field, first base, and even pitched to a couple of batters (walking both). Though he was left-handed, Mayer hit from the right side of the plate. Mayer was not much better than the semi-pro hackers Walter had faced in New Jersey, and he would have been the willing victim of a sinking changeup. Mayer swung over the top and grounded back to Ancker, who tossed the ball to Stuffy McInnis covering first.

The damage: no runs, no hits, no errors, three left on base. It wasn’t pretty with two walks and a hit batter. But no one had gotten the ball out of the infield, and no one had scored. In the bottom of the first the Athletics gave Ancker a nice cushion by scoring four runs off Gallia.

The second inning was relatively smooth as Ancker faced only four batters. Washington was retired with a fly ball, a single to left, and two ground outs.

The third inning was a shakier affair. The always dangerous Eddie Foster led off the inning by grounding to Stuffy McInnis at first. ‘Deerfoot’ Milan walked. He took a big lead, thinking that second base would be an easy steal with an unproven pitcher and a second-string catcher. But Ancker caught him leaning and made a quick pickoff move to first. McInnis, the last remnant of the $100,000 Infield, took the throw and slapped the tag on Milan for the first out. Shanks, the cleanup hitter, also walked — two walks in a row for Ancker. Then the scowling Chick Gandil whacked the ball straight up the middle through Ancker’s legs for a single, moving Shanks to second. Ancker walked Mayer, his third walk of the inning, to again load the bases. But catcher Alva Williams flied to left to end the inning.

It was another near-disaster: one hit and three walks, three left on base, but no runs. As in the first inning, Ancker was wild and met the typical baseball definition of in trouble. But he worked out of it without giving up a run. After that final semi-pro game against Oritani, the writer for the Hackensack Record had reported, ‘At times he showed an inclination at wildness, but the bigger the hole he got in the more air-tight he became.’ Ancker was definitely digging deep holes, but he was thus far airtight, at least as far as runs were concerned. And the Athletics added another run in the bottom of the inning to make the game 5-0.

Ancker got back on track in the fourth inning. He faced four batters, giving up a single and getting the three outs on flies and grounders. He didn’t walk or hit anyone.

When Ancker strolled to the mound in the top of the fifth inning he was pitching a very messy shutout. He had so far walked five batters, drilled one, and given up three hits. He had loaded the bases twice, but no one had scored. He was working out of trouble though probably throwing a lot of pitches. It was here that the wheels fell off the wagon.

The inning started well. Milan grounded out to second baseman Lew Malone, another rookie being given a tryout by Connie Mack, and Shanks flied to left. Then Chick Gandil glared his way into a walk, his second of the game.

With two outs and a runner at first, Sam Mayer bit on another drop ball and sent a grounder to the 41-year-old Lajoie at shortstop. Ancker could not have hoped for a better result. The ball was going towards one of the best fielders to ever play the game. Lajoie was well beyond his prime and wasn’t playing his usual position, but the inning was about to be over. Ancker was stepping toward the dugout when Lajoie fumbled the grounder and Mayer reached on an error as Gandil raced to second.

Ancker was unnerved by witnessing the rare error by Lajoie, the baseball equivalent of taking a walk in the New Jersey woods and encountering Sasquatch. Alva Williams singled to right, scoring Gandil — an unearned run since the grounder to Lajoie should have ended the inning — while Mayer held up at second. Ancker then walked shortstop George McBride to again load the bases. The next batter was the pitcher, Bert Gallia. Gallia should have been an easy out, and with the bases loaded the Athletics had a potential force at every bag. But Ancker uncorked a wild pitch. As the ball caromed toward the backstop Mayer scored from third — another unearned run — and Williams and McBride advanced. Returning to Gallia, Ancker walked the pitcher — a major league no-no — to load the bases yet again and was promptly banished to the bench by Connie Mack.

Ancker was relieved by Tom Knowlson, who induced a fly ball from Acosta to end the inning with the Athletics leading 5-2. Washington came back to tie the game in the top of the eighth, but Philadelphia regained the lead in the bottom of the inning. The final score: 6-5 with Knowlson, who pitched the remainder of the game after taking over for Ancker, being credited with the win.

Pitching four-and-two-thirds innings, Ancker allowed four hits, walked eight, hit a batter, made a wild pitch, and gave up two unearned runs. Writing for the Washington Post, Stanley T. Milliken offered a brutal assessment of the outing: ‘Ancker had no idea what the plate was for.’

The hometown Evening Public Ledger offered scant commentary on the game, other than to say, ‘There were less than 300 people on hand to see the game today and they did not enthuse at the breaking of the losing streak.’

The Public Ledger’s game summary appeared just to the right of a first-person column by future Hall of Fame pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, on his way to a 31-win season with the National League’s Philadelphia Phillies. Discussing the issue of pitching with control, Old Pete’s words could have been addressed directly to Walter Ancker: ‘Control is the one great asset for any pitcher. If he can’t place the baseball just about where he wants it to go, he might just as well give up big league flinging. A man can have all the curves and speed in the world, but they won’t get him anywhere in his profession unless he can control them.’

After the second game of the double-header, with Ancker’s performance fresh in his memory, Connie Mack unburdened himself to the assembled sportswriters. ‘If you’ll consult the records,’ Mack said, ‘you will find, I believe, that my pitchers this year have established a record for wildness that will probably live for all time. I have young pitchers of promise who are wilder than any I have ever seen. Nothing is more demoralizing to a ball club that a wild pitcher. Therefore my team has been somewhat demoralized at times. But I resent the accusation that my club is the worst team on earth.’ That distinction would go to his team the following year.

Walter Ancker made his third major league appearance on Saturday, September 11, 1915 in a four-inning relief outing against the St. Louis Browns.

In the big news of that day, Philadelphia broke ground on the city’s new subway system. Thousands of spectators assembled in the City Hall plaza to see Mayor Rudolph Blankenburg turn over a shovelful of dirt and proclaim, ‘We are making history!’

D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation was playing at the Forrest Theater, where the accompaniment was provided by a symphony orchestra of forty musicians. The newspaper advertisements labeled the film the greatest art conquest since the beginning of civilization.

A heat wave had enveloped Philadelphia. The city’s Bureau of Health announced that 473 residents had died in the past week, a jump of 101 over the previous week. The increase was attributed to the ‘exceptionally hot weather.’ Leading the tally of causes, with 75, was diarrhea and enteritis in infants under two years of age. Tuberculosis contributed 58 deaths, and typhoid fever accounted for 33. The United States Health Service estimated that typhoid would cause 18,000 deaths nationwide before the end of the year.

The Athletics and the St. Louis Browns were playing a double-header. The first game started at 1:30PM, under clear skies and a temperature of 90 degrees. Many citizens had escaped the heat by taking a train to the seashore, but 1200 were on hand at Shibe Park where the shade of the grandstands offered some relief from the sun.

The Browns had originally been the Milwaukee Brewers. They moved to St. Louis in 1902 where they remained for 52 years before relocating to Baltimore and becoming the Orioles. The current Milwaukee Brewers franchise began life as the Seattle Pilots before flying to Milwaukee in 1970. In 1915 the Browns were managed by Branch Rickey, a lawyer by training, and in the newspapers they were clumsily referred to as the ‘Rickeyites.’ Branch Rickey would go on to become the General Manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, where he was responsible for bringing Jackie Robinson into the major leagues.

The Browns were terrible in 1915 — though not as bad as the Athletics — as Rickey had also avoided the bidding war with the Federal League and was trying out a string of raw recruits. After going on a five-game mid-September winning streak, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch sarcastically declared in a headline that the team was NOW ONLY 33 1/2 GAMES FROM LEAD!

The day did not belong to the Athletics. They lost the first game 8-4. Connie Mack trotted out three of his kid flingers — Jack Nabors, Bruno Haas, and Dana Fillingim — all of whom were in their first major league season. It proved to be the only season for Haas. When he took the mound in the top of the sixth inning he lasted two batters, giving up a single and a walk, before being yanked and sent to the showers. The game lasted over two hours, long for those days.

The second game of the double-header commenced around 4PM. The park had cooled off a bit, maybe down to 86 degrees. A few clouds were creeping in, and by evening those returning from the shore would emerge from the station into a light rain.

In a rare move, Mack started a veteran pitcher. Though only 22 years old and technically still a kid flinger, Bullet Joe Bush had been a significant contributor to Mack’s championship teams, winning 15 games in 1913 and 17 games in 1914. But without a solid cast to back him up, Bush’s fortunes plummeted. He would end 1915 with a 5-15 record. And his 15-24 record in 1916 would lead the majors in losses while accounting for 42% of Philadelphia’s 36 total wins.

Pitching five innings, Bush gave up seven runs on ten hits, walked four, and made a wild pitch. Bush Bombarded was the alliterative headline in Sunday’s St. Louis Globe-Democrat. Walter Ancker took over in the top of the sixth inning with the Athletics trailing 4-7. A batter-by-batter summary of the game is not available, but we can glean a few insights from the newspaper reports.

Ancker started well, striking out St. Louis catcher Muddy Ruel. Pitcher Carl Weilman singled — at over 6-foot-five-inches he was the tallest pitcher in the American league and was described by the St, Louis Post-Dispatch as the ‘elongated left-hander’ — but Ancker expunged the next batters on a fly and a grounder.

The seventh inning was another Walter Ancker Special. The leadoff batter was rookie first baseman and future Hall of Famer George Sisler. He was the same age as Ancker but his talent was already evident. Sisler would go on to a 15-year major league career, twice batting over .400 and ending with a .340 lifetime average. Ancker retired Sisler and the Browns’ cleanup hitter, second baseman Del Pratt. With two outs and the best hitters behind him, Ancker should have been in the clear. The next batter was Billy Lee, a rookie outfielder with a batting average below the Mendoza Line. He personified the label good field, no hit. But Lee whacked a single to keep the Browns alive. Shaken by the unexpected turn of events, Ancker lost the plot and walked three straight batters to score Lee before finally bagging the lanky Weilman.

It was a horrible performance: a single and three walks after recording two outs. The inning was eerily similar to his outing against the Senators when, with two outs, he became rattled after Lajoie’s fielding error on what should have been the last pitch of the frame.

The eighth inning was a We’re Not in New Jersey Anymore moment. Ancker sat down St. Louis left fielder Burt Shotton, who in 1947 would be hired by Branch Rickey to manage the Brooklyn Dodgers in Jackie Robinson’s rookie season. But Ancker walked third baseman Ivan Howard, who promptly stole second. Del Pratt singled, moving Howard to third. Then Pratt and Howard pulled off a rare double-steal — a double purloin according to the Philadelphia Inquirer — and Howard scored standing up. At that point, Walter Ancker may have been longing for the friendly fields of Tenafly.

The ninth inning passed uneventfully (or, at least, nothing happened worth reporting in the papers). The end result: in four innings Ancker allowed two runs on four hits. He walked four, but didn’t hit any batters and didn’t make any wild pitches. And the box score indicates that he struck out three batters, suggesting that his curve and changeup were working. It was another head-scratching performance. Sometimes Ancker pitched like a major leaguer, and sometimes he couldn’t find the plate. He seemed unable to put together two solid innings in a row.

The beat writer for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch succinctly summarized Ancker’s outing: ‘A rookie from New Jersey named Ancker finished.’

Walter Ancker’s final major league appearance came just three days later, on Tuesday, September 14, 1915 against the St. Louis Browns at Shibe Park. The heat wave that had been in evidence during Ancker’s previous outing still embroiled the city. It was the hottest September 14 in the history of the Philadelphia weather bureau. That day the heat killed one, a 66-year-old man, and caused four ‘prostrations.’ Among the prostrated was an unidentified girl who was overcome at 16th and Vine Streets and was carried unconscious to the Hahnemann Hospital.

Despite the high temperatures and the Evening Public Ledger’s headlined forecast of NO RELIEF IN SIGHT, September 14 was the last day for fashionable men to wear straw hats. An estimated 500,000 straw hats would be discarded in the city the next day. Placed end-to-end, the hats would reach from Philadelphia to Topeka, Kansas. The boaters on the heads of the 500 fans who turned up at Shibe Park would have reached from the backstop to the fence in straightaway center field.

The game commenced at 3:30PM with the mercury at 90 degrees. Connie Mack sent Tom Knowlson to the mound. He lasted only an inning, giving up a triple, a single, and three walks. But thanks to Philadelphia’s good defense, and poor baserunning by St. Louis, he gave up just one run. Weldon Wyckoff took the mound in the second inning but fared no better, giving up six runs on four hits and three walks before being lifted for a pinch hitter in the fifth.

Branch Rickey countered with James Park, who was being given a late-season tryout before returning to his job as an assistant football coach at Kentucky State University. Park pitched effectively, holding the Athletics to three runs over seven innings.

When Walter Ancker entered the match in the top of the sixth, with the score 1-7 in favor of the Browns, the thermometer was still nudging 90 degrees. He retired the batters three up, three down with a fly ball and two grounders. In the next inning Ancker again faced only three batters. Though he gave up two singles, both runners were caught stealing.

Ancker’s final frames were a mess. Over the course of two innings the Browns nailed him for two singles, a double, a home run, and three walks, allowing five runs. Maybe it was the heat; maybe all those innings that he’d piled up back in New Jersey were wearing on him. It’s the line score of a pitcher whose breaking stuff is missing the strike zone, and whose fast ball is an inviting target. The game ended 4-12 in another depressing loss for the Athletics.

For the spectators, the only bright spot in Ancker’s outing arrived on his last pitch of the eighth inning. With the bases loaded, George Sisler pulled one into deep right field. The runners on second and third raced home. Ivan Howard took off from first base and lumbered around second, following his heart towards third base. Ireland-born Jimmy Walsh fielded the ball cleanly in right field and fired it to Lajoie, waiting at the edge of the outfield grass. And when the ball touched the glove, it was not caught by a 41-year-old infielder. The Ghost of Lajoie Past now occupied the uniform. In a single fluid movement he took the throw and, with the grace of a man twenty years younger, made a perfect pirouette and fired the ball to Rube Oldring at third who placed the tag on Howard for the final out.

The fans were on their feet and cheering, having glimpsed a soul not seen since the days when giants ran rampant on the diamond. Some threw their straw hats into the air and did not bother to retrieve them, as the boaters would fall from fashion the following day. But when Lajoie reached the dugout and glanced up, the fans saw that he was 41 again.

It was said that every contract issued by Connie Mack in 1915 came with a round trip train ticket attached. Walter Ancker probably used his to return to Tenafly after the disaster against the Browns. Connie Mack was still churning his roster and told the sportswriters that, by the end of the year, all of his current players would be gone. One wag suggested that, after schools reopened, Mack would be able to tour the local kindergartens in search of material.

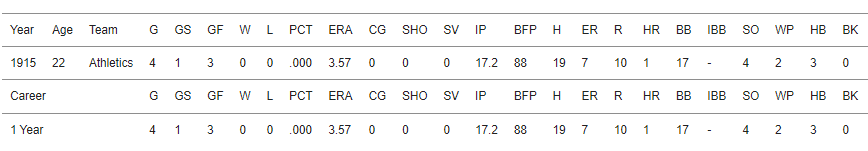

Walter Ancker’s major league career was over. He’d finished his cup of coffee and was headed back to Hackensack. He had appeared in four games over the course of twelve days, starting one and relieving in three others. In 17 2/3 innings he allowed 10 runs on 19 hits, struck out 4, walked 17, hit three batters, and made 2 wild pitches. His final won-lost record: 0-0.

But the 88 batters Ancker faced included some of the best hitters in baseball history, players like Tris Speaker and George Sisler. He had shared the infield with the great Lajoie. His manager was Connie Mack. Ancker had not exactly blazed through the majors like a shooting star. But Ancker’s outings amounted to a richer slice of baseball than is reflected in the simple stat table that summarizes Ancker’s abbreviated season.

Walter Ancker’s Standard Pitching Stats. From Baseball Almanac.

Walter Ancker’s Standard Pitching Stats. From Baseball Almanac.

In the last weeks of September, after Walter Ancker had otherwise vanished from the sports pages, a spate of puns appeared that give a clue as to the proper pronunciation of his name.

Ancker, of the Athletics, is dragging. — Washington Times, September 17, 1915

Connie Mack doesn’t care how he treats his men. Now an Eastern paper laments that the Athletics are dragging their Ancker. — Pittsburgh Daily Post, September 20, 1915

Now that Connie Mack has an Ancker there is no way out of the cellar for him. — Vancouver Sun, September 24, 1915

—–

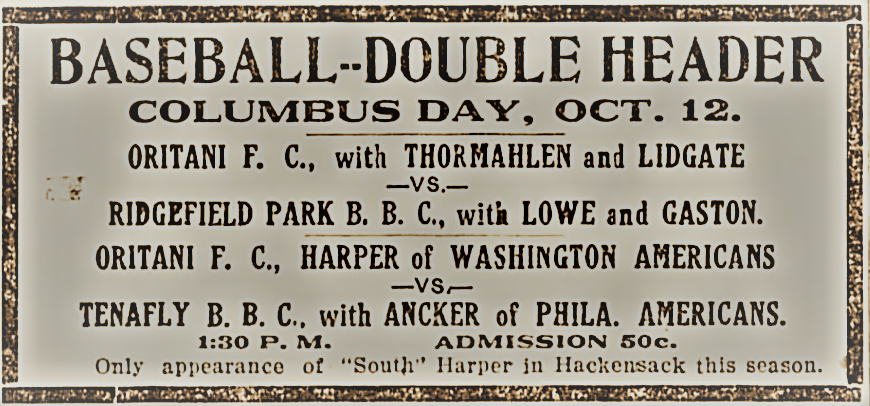

Advertisement in the Hackensack Record, October 11, 1915.

Advertisement in the Hackensack Record, October 11, 1915.

The sixteen teams of the American and National leagues completed their regular season on October 7, 1915 with the New York Giants defeating the Boston Braves and the Boston Red Sox losing to the New York Yankees. The World Series pitting the American League’s Red Sox against the National League’s Philadelphia Phillies began the very next day. The series ended on October 13 with the Red Sox winning in five games. In those days, it was still the October Classic.

Tuesday, October 12, was Columbus Day. After lunch a large crowd gathered at the Oritani Field Club in Hackensack to watch the Indians play a double header. Over in Boston, the Red Sox were defeating the Phillies. The first radio broadcast of a World Series game was still six years away, but the batter-by-batter results were telegraphed from Boston to the Western Union office in Hackensack. A stream of youngsters carried reports of the game’s progress down Main Street to the baseball field that was just off the corner of Main and East Camden. It was a nine-minute walk, but the boys were expected to run.

In the first game, Oritani took on the Ridgefield Park Baseball Club. But most fans were there for the second matchup, Oritani vs. Tenafly. The gamed featured two local flingers who had escaped Bergen County to pitch in the majors. Harry Harper would take the mound for Oritani, while Walter Ancker would twirl for Tenafly.

Harper was a true kid flinger having broken into the majors two years earlier when he was just 18. In 1915 he appeared in 19 games with the Washington Senators, compiling a 4-4 record. He was a left-hander — a southpaw — and was known as ‘South’ Harper. Later he would be dubbed ‘Hackensack Harry’ after becoming a prominent Bergen County businessman and politician.

Harper was a true kid flinger having broken into the majors two years earlier when he was just 18. In 1915 he appeared in 19 games with the Washington Senators, compiling a 4-4 record. He was a left-hander — a southpaw — and was known as ‘South’ Harper. Later he would be dubbed ‘Hackensack Harry’ after becoming a prominent Bergen County businessman and politician.

Harper had eight years of education, dropping out before high school. He came to the attention of major league scouts by, like Walter Ancker, burning up the Bergen County semi-pro hackers. He had already commenced a somewhat Tony Soprano-esque business career. After signing his contract with the Senators, he used his money to start a garbage collection company. He then expanded into trucking and hauled the concrete that built the Holland Tunnel and the Catskills Aqueduct. One does not obtain such contracts without connections. He later moved into the grocery, fuel, and beverage industries.

Pitching for Oritani, Harper sliced through the Tenafly batters. Over nine innings he gave up no hits and no runs while striking out either twenty or twenty-one, depending on whether one read the Bridgewater Courier-News or the Hackensack Record. Ancker was just a shade behind Harper, allowing three hits and no runs, striking out either seventeen or sixteen. The evident lesson was that even a mediocre major league pitcher could mow down Bergen County’s semi-pro hitters. But Ancker had learned that the distance from Hackensack to Shibe Park was more than sixty-feet-six inches.

With sunset approaching, the match ended in a 0-0 tie after nine innings. The result no doubt confounded the gamblers, other than the handful who had cannily bet on a tie. The Record proclaimed it the best pitchers dual [sic] ever seen here. Twelve years later the contest was still fresh in the mind of an old Bergen County baseball man, who recalled it as that memorable game.

Harper was just two batters shy of a perfect game. He gave up a walk and allowed a runner to reach on an uncaught third strike. The latter play took place in the ninth inning, part of a sequence that could only be experienced in the wild world of semi-pro baseball.

A player named Vossler, one of three Vosslers in the Tenafly lineup, swung on an uncatchable wild pitch for strike three, allowing him to steal first. As the ball was tracked down by the Oritani catcher, Harry Harper’s brother Walter, Vossler scampered all the way to second base. A few pitches later he stole third. Meanwhile, Harper retired two Tenafly batsmen. With two outs, darkness on the horizon, and Harper unhittable, Vossler tried to win the game the only way that he could: by stealing home.

A successful steal of home requires speed, timing, bravery, luck, and surprise. It is a discarded tactic in the current era, where the prevailing strategy is to reduce risk and wait for someone to hit a home run. Most baseball players will go their entire career without attempting to steal home. Vossler attempted to steal home four times during a single at-bat. Three times Vossler crept down the line and broke for home when Harper’s windup passed the point of no return, and three times the Tenafly hitter, shortstop J. Miles, fouled off the pitches. On the fourth attempt Miles kept the bat on his shoulder as Vossler, having long ago abandoned the element of surprise, again sprinted for home. He slid across the plate in a great cloud of New Jersey dust but was tagged out on what would have been ball four.

Oritani Field Club, Hackensack, New Jersey circa 1911.

Oritani Field Club, Hackensack, New Jersey circa 1911.

Walter Ancker closed out his 1915 season on Saturday, October 16. In another game played at Oritani Field, a team of local All Stars took on a barnstorming squad led by Rube Marquard. Ancker, recognized as the best pitcher in the area, pitched for the All Stars.

Marquard was a very good — perhaps not great — left-handed pitcher. When he appeared at Oritani Field he had just completed his eighth major league season, compiling an 11-10 record pitching for the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Robins. He would eventually string out 201 wins over an 18-season span. The highlight of Marquard’s career arrived in 1912, when he won 19 games in a row, the most consecutive games won by a pitcher in a single season. He shares the record with Tim Keefe (1888) and Gerrit Cole (2019).

Marquard was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1971. The selection has been criticized by the analytics community, whose advanced and incomprehensible statistics suggest that Rube was an average pitcher for his day. Bill James dubbed Marquard the worst starting pitcher in the Hall of Fame.

The Hackensack fans did not possess such fine insight, and a good crowd turned out to witness Marquard twirl his benders. Though Marquard’s team was advertised as being ‘cracks’ — major leaguers — most of his players were little better than the semi-pros Ancker had pitched against in Tenafly.

Marquard’s most experienced player was catcher Larry McLean, whose 13-season major league career had come to an abrupt halt the previous June. The six-foot-five, 228-pound McLean attacked his manager, the New York Giants’ John McGraw. Scout Dick Kinsella broke a chair over McLean’s head without effect, and McLean fled the scene — and the majors — in a car. Six years later, McLean became intoxicated in a Prohibition-era speakeasy and attacked the manager — he must have had a problem with managers — who pulled out a gun and killed McLean with a single shot.

Ancker’s day began in familiar fashion. He gave up a single to Bill Holden, whose two-season major league career had ended in 1914 with a .211 lifetime batting average. Holden stole second and advanced from second to home on a series of wild pitches. But that was the limit for Marquard’s team, as Walter held them scoreless for the remainder of the game. Over nine innings Ancker allowed one run on two hits, struck out nine, walked two, and hit a batter.

Marquard scattered five hits over nine innings, struck out thirteen, and didn’t walk or hit any batters. The score remained 1-0 in favor of Marquard until the bottom of the ninth when, with a runner on first, the All Stars’ Alex Gaston smacked a ball over the center field fence to end the game. It was Gaston’s second homer at Oritani Field that week. As far as the old timers could recall, no one had ever before hit two home runs at Oritani Field in one week. Gaston made the majors five years later, breaking in as a 27-year-old rookie. He played in parts of six seasons, ending his major league career in 1929 at the age of 36.

The Monday after the game against Marquard, Walter Ancker sent a letter to Connie Mack inquiring about his status for the following season. And, in a canny bit of self-promotion, he seems to have mentioned his performances against Marquard and Harper. He may have enclosed the box scores clipped from the Hackensack Record. Ancker’s letter to Mack has not been preserved, but Connie Mack’s reply, typed on the stationary of the American Baseball Club of Philadelphia and signed legibly in ink, is now in the Hall of Fame collection.

Dear Walter:

Yours of the 19th.,inst., received. I also have the box scores of the game that Harper, and Yourself worked. I also saw where you won from Marquad [sic]. I feel that with another year of experience that you ought to be able to deliver the goods. I trust you will have a very pleasant winter, and a little later on, will let you know what our plans are for the coming Spring.

With very best wishes, I remain,

Sincerely yours,

Connie Mack

Walter Ancker’s additional year of experience would begin the following March with a train trip to Asheville, North Carolina.

—–