Trials of a Minor League Umpire in 1909

Are you blind? Where do you think you are? In a cow-pasture?

— Thomas Wolfe, A Portrait of Bascom Hawke

The cash-poor lower leagues of the South assigned a single umpire to each game. Most worked behind the plate until a runner reached base, then took a position behind the mound. One official could not cover the entire field, and umpires made bad calls in every game. The fans and players heaped abuse on the ump following every perceived slight.

During the 1909 season, the verbal abuse often morphed into physical violence.

Umpire’s indicator, early 1900s. The umpire was said to “hold the indicator.”

Umpire’s indicator, early 1900s. The umpire was said to “hold the indicator.”

In the Class C South Atlantic League, Linwood Bailey, a former pitcher known around the circuit as “King,” umpired a June 11 game between the Columbia Gamecocks and the Augusta Tourists in Columbia’s Elmwood Park. The 700 fans in attendance were already on edge. Temperatures topped 90 degrees, and that morning the body of a 41-year-old mother of five had been found in the well behind her home on South Sumter Street. The murderer slashed her throat and smashed her face with an ax.

In the bottom of the ninth, with Augusta leading 3-2 and a Gamecock on first base, the Columbia batter dropped a sure three-bagger far down the left-field foul line. The runner on first raced around the bases to score and knot the game.

The determination of “fair” or “foul” was difficult to make when standing behind the pitcher, especially when the lines were merely scratches in the weed-choked sand, and Bailey yelled Foul ball!

The spectators in the grandstand behind home plate, who possessed a better angle on the play than Bailey, saw that the ball had dropped at least two feet inside the line. The crowd erupted, and the Columbia players jumped from their bench and surrounded Bailey. The ump fined each player between $5 and $15, depending on the language the player used to express his displeasure. The fans joined the fray, boiling over the front of the grandstand.

The ever-present squad of policemen arrived and restored sufficient order for the game to continue. But after the final out revealed a Columbia loss, the fans again swarmed the field in search of Bailey’s blood.

Bailey grabbed a bat to defend himself, but Charles Manship, the assistant manager of the Royster Guano Company, stepped in and disarmed the ump. A policeman, accompanied by City Recorder C.A. Stanley, arrived and hustled Bailey into the space between the back of the grandstand and the fence that separated the ballpark from Elmwood Avenue. Three policemen kept the crowd from entering the alleyway.

Although momentarily safe from the fans, Bailey now had to deal with Recorder Stanley. His Honor leaped upon Bailey and began choking him. Columbia manager Arthur Granville came to Bailey’s rescue, pried Stanley’s fingers from the umpire’s throat, and guided him into the clubhouse.

The mob moved from the field to Elmwood Avenue and started prying planks from the fence fronting the clubhouse. They had removed two planks when Gatekeeper George Radcliff climbed onto the clubhouse roof and admonished them for destroying the team’s property. His words carried weight – probably because Mr. Radcliff would be required to make the repairs – and the crowd satisfied itself with milling around in the middle of Elmwood.

Recorder Stanley used the clubhouse phone to call police headquarters, and within a few minutes the patrol wagon came clattering down Elmwood, its brass bell clanging to clear the crowd. The driver parked the wagon near the gate, and two officers, two detectives, and Police Chief W.C. Cathcart emerged from the rear door and entered the ballpark. The scrum of policemen escorted Bailey to the wagon and hauled him to the Main Street Police Station for safekeeping.

The officers entertained Bailey in the station house until 8 o’clock that night, probably giving him the inside scoop on the Sumter Street murder. He left Columbia immediately, without bothering to telegraph his resignation to the league office and swearing that his umpiring days were over.

“The curtain fell on the last scene of a play entitled ‘Robbery in the Park,’” wrote J.B. Crews, the sports editor of the Columbia Record. “The game and its subsequent features were the topic of talk everywhere last night. The murder mystery of South Sumter Street, the hot weather, and other favorite topics were for the time forgotten and the incidents of the afternoon at Elmwood were the piece de resistance of the hour.”

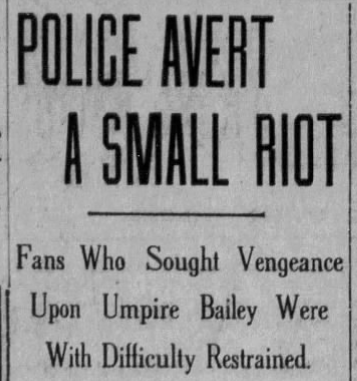

Columbia Record, June 12, 1909.

Columbia Record, June 12, 1909.

Linwood Bailey returned home to Macon, Georgia, and entered the insurance business. He died of septicemia in 1917 at age 48. His obituary in the Macon Telegraph noted that Bailey possessed “an amiable disposition and scores of close friends in the city.”

Like King Bailey, umpire Cornelius “Con” Lucid was an ex-ballplayer. Born in Ireland, he spent parts of nine seasons in professional ball. His most successful year came in 1895 when he compiled a 16-10 record pitching for the National League’s Brooklyn Grooms and Philadelphia Phillies.

Lucid began the 1909 season umping in the Texas League, then moved to the South Atlantic League.

Most umpires disdained the chest protector – it was hot and hindered their ability to cover the entire diamond – leaving them vulnerable to foul tips. In a May 7 game, Lucid received half a dozen shots to the body. He missed the next game, confined to his bed and too sore to turn over.

He was probably still aching on May 12 when he took the field for a game between Columbia and the Macon Peaches. With the score tied 2-2 after 11 innings, Lucid called the affair a draw due to darkness. The game had started at 4 pm and lasted two hours and thirty-eight minutes. With the sun setting at 7:16 pm, the teams could have eked out another 20 to 30 minutes of play.

Both clubs kicked. The protest was performative for Columbia, in sixth place with an 8-12 record. Macon’s stakes were higher: their 12-10 record was good for fourth place, a single game behind Jacksonville. Their manager lodged a vigorous but futile complaint.

It’s likely that Lucid, not fully recovered from the beating he had taken five days before, needed to get off his feet and into a soft bed. But the newspapermen were less than sympathetic.

“It was the very worst stunt any umpire, anywhere, at any time ever pulled off,” railed the Macon Telegraph’s columnist, writing under the pseudonym of Toby. “It is reported tonight that Umpire Lucid has accepted terms as a coacher for the state blind asylum.”

The Macon News took a more nuanced tone, blaming Lucid’s decision on a skipped meal: “The game was declared a draw by Umpire Lucid just about the time he felt hungry. Here is a tip to Lucid – don’t miss your luncheon and then you can be able to umpire until darkness.”

Macon News, May 13, 1909.

Macon News, May 13, 1909.

The South Atlantic League fired Lucid a few days after the Columbia-Macon incident. The Telegraph’s Toby delighted in the discharge: “Umpire Lucid, the blind man, who worked out such a horrible exhibition against the Elbertas [a type of peach] in Columbia this week, has been given his release.”

Moving upcountry, Lucid found work in the Class D Carolina Association, where his work received positive reviews. When the Texas League offered him a higher salary, the Carolina Association managers submitted a petition urging league president J.H. Wearn to give Lucid a raise.

While Lucid’s calls were acceptable, the voice used to make them was incomprehensible to the languid-tongued Carolinians.

“The only way a spectator can keep up with strikes and balls is by the motion of his hand, but the number of each no one can understand from his voice,” the Greensboro Record complained. “He might talk a little slower and not jerk it out so fast and furiously. ‘StrkONE, bllONE’ is hard to catch on to, though he uses his arms all right, but you can’t tell how many balls or strikes a batter has.”

Lucid remained in the Carolina Association but received a blow from a batted ball on June 15 and missed nearly two weeks of games. When he returned, he immediately ran afoul of the fans. On his first day back, still hurting and enduring temperatures near 90, Lucid grew weary of being derided by the cranks in Greensboro’s Cone Park.

He approached the grandstand and attempted to have one of his more vocal tormentors removed from the park. The police refused his request, which only encouraged the crowd. “It waxed pretty warm for a while,” the Greensboro Record reported.

The Record took Lucid to task for his actions: “Mr. Lucid may be a competent umpire, but he has very poor judgment. An umpire who tries to control the grand stand is sadly wanting in sense. In fact the umpire who pays the least head to the rooters is on the road to the bughouse.”

When Lucid complained to the league office about the abuse in Cone Park, the Record passed it off, saying, “He has not been subjected to it here more than any umpire in any other city.”

Greensboro’s Cone Athletic Park circa 1908. The umpire (in black) is behind the pitcher. Bernard Cone Collection.

Greensboro’s Cone Athletic Park circa 1908. The umpire (in black) is behind the pitcher. Bernard Cone Collection.

Closeup of the umpire (in black) behind the pitcher in Cone Park circa 1908. Bernard Cone Collection.

Closeup of the umpire (in black) behind the pitcher in Cone Park circa 1908. Bernard Cone Collection.

An umpire (in black) behind the pitcher in Greensboro’s Cone Park circa 1908. Bernard Cone Collection.

An umpire (in black) behind the pitcher in Greensboro’s Cone Park circa 1908. Bernard Cone Collection.

Independence Day fell on a Sunday in 1909, pushing the annual celebration into Monday. Businesses around the south closed, and most teams scheduled doubleheaders. Lucid held the indicator for a pair of games between the Greenville Spinners and the Spartanburg Musicians.

The Spinners took the morning game, played in Spartanburg before 1600 fans. The teams – and Lucid – then traveled 30 miles by rail to Greenville for the afternoon match.

Over 3000 spectators packed into League Park to watch the Spinners lose to the Musicians 3-8. “The exhibition abounded in listless playing and was characterized by poor umpiring,” the Columbia State noted, though the newspaper did not provide details of Lucid’s deficiencies.

After the game, an unhappy fan accosted Lucid and placed his hand on his hip as if to draw a gun. Lucid held the man off with a bat – one gets the impression that umpires always walked around with a bat for self-defense – until Police Chief R.H. Kennedy swooped in and led the rowdy away. He was, it turned out, armed only with his delusions. The Charlotte Observer said the fan “had imbibed too freely in some liquid not akin to aqua pura.”

Cornelius Lucid left the Carolina Association before the season ended and returned to Texas. He was an assistant coach for the Houston Buffalos of the Class B Texas League from 1912 through 1914 and managed the Texas A&M baseball team in 1915. Lucid died in 1931. Although his entry in the Find A Grave database suggests he committed suicide, his death certificate lists angina pectoris as the cause of death.

When the South Atlantic League fired Con Lucid after he prematurely ended the tied game, Frank B. Butler, a Savannah resident, replaced him on the circuit’s umpire staff.

An undersized outfielder known for his exceptional speed, Butler played parts of nine seasons in professional ball. When he broke into the minors with the Class B Southern Association’s Macon club in 1892, the 25-year-old was five-foot-seven, 145 pounds, and could circle the diamond in 11 seconds. Butler’s high-pitched voice did not serve him well as an umpire. “He is as small in stature as his voice is shrill,” an observer said.

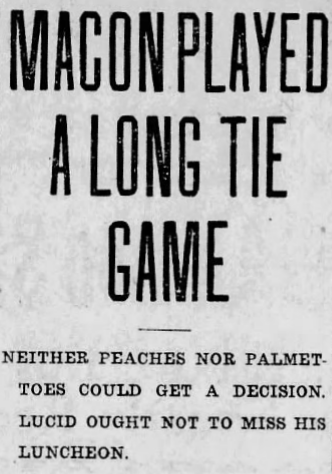

By 1895, Butler was with the Southern Association’s Nashville Seraphs. In a team photograph, Butler, sporting an Ansonian mustache, looks tiny standing beside six-foot catcher Mike Trost.

Frank Butler (back row, far right) with the Nashville Seraphs in 1895.

Frank Butler (back row, far right) with the Nashville Seraphs in 1895.

In late July, the Seraphs sold Butler’s contract to the New York Giants for $1000, a large sum for that era. He joined the Giants on a road trip, batting leadoff and playing left field. He made a good initial impression, legging out an infield hit in his first at-bat.

But on August 2, with the Giants scheduled to begin a home series against the rival Brooklyn Grooms the next day, a columnist for the New York Evening World foretold Butler’s demise: “Left-Fielder Butler will have a new experience on the Polo Grounds. It is notorious that the man who plays that position on the Harlem field has a dazzling sun shining straight into his eyes, and gauging flies is no easy task under such circumstances.”

In the first inning of his first game in the Polo Grounds, a Brooklyn batter drove the ball over Butler’s head for a triple, then came home when Butler made a wild throw to the infield. The Giants released Butler the next day, his major league career over after five games.

Thereafter, Frank Butler was known as “Gold Brick Butler” or “the Southern Gold Brick.”

Butler returned to the minors and enjoyed some good years with the Columbus Senators of the Class A Western League, the circuit that later became the American League. He batted .342 in 1897.

Independence Day of 1898 found Butler and the Senators in Indianapolis for a doubleheader against the local Hoosiers. The US Army’s recent victory at San Juan Hill had sent the entire country into a paroxysm of celebration.

Five thousand fans turned out for the afternoon contest, completely filling the stands and overflowing onto the field. “Nine out of every ten of the spectators came armed with firecrackers, ranging in size from a quarter of an inch to a foot long,” the Indianapolis News reported. “Many of them also brought revolvers, and when the Indianapolis team walked on the field the players were greeted with volley after volley which enveloped the men in smoke and filled the air with powder, a popular odor just now.”

The barrage continued during the game as the cranks attempted to distract the Senators by throwing firecrackers onto the field. A large specimen known as a cannon cracker failed to explode. Pitcher Bumpus Jones, Butler’s roommate, picked it up and took it back to the hotel where the team was staying.

That evening, Butler began to toy with the cannon cracker and, holding it in his left hand, put a match to the stubby fuse. The firecracker sputtered to life and exploded.

The detonation blew away two fingers on Butler’s left hand, and a later operation removed two bones near the base of his thumb. Though Butler was a right-handed thrower, he batted lefty, and the injury made it impossible for him to grip a bat.

Butler experimented with various mechanical aids. He finally devised a glove with a leather crotch on which the bat rested. The device proved effective enough for Butler to return to the minors. He played a handful of early-season games with Columbus in 1899 and 61 games with the Southern Association’s Chattanooga Lookouts in 1901.

He continued playing semi-pro ball for a few more seasons; as late as 1905, the Savannah city directory listed Butler’s occupation as prof baseball player.

Butler married fortuitously. His wife, Lula (Louisa) O’Keefe, was the daughter of David O’Keefe, a ship’s captain known as the King of Yap.

In the early 1870s, O’Keefe established a copra exporting business on the western Pacific island of Yap. He financed his endeavors by manufacturing Rai stones, the enormous limestone disks used as currency by the Yapanese. Using Western tools and ships, O’Keefe could carve and transport the stones more easily than the locals, though increasing the supply of stones reduced their value. His Majesty O’Keefe, a 1954 movie starring Burt Lancaster, told a highly fictionalized version of O’Keefe’s life in the Pacific.

David O’Keefe, Atlanta Journal, April 24, 1921.

David O’Keefe, Atlanta Journal, April 24, 1921.

When O’Keefe died in 1901, he left a trading business on Yap (controlled by Germany) worth $250,000 and an investment portfolio in Hong Kong (a British colony) worth another $250,000. The estate topped $18,000,000 in today’s money.

The Butlers hired a San Francisco law firm to claim a share of the bounty, and Mr. Walter C. Hartridge spent years traveling between the US, Yap, Hong Kong, and Hamburg. The various authorities ultimately decided that Lula Butler would receive half of the estate, with the other half split between the children that O’Keefe had fathered with his multiple Yapanese wives.

How much of the money made its way to Savannah is questionable. In 1920, Lula Butler, her five children, her mother, and an aunt lived together in a multi-family building at what is now the corner of East Broughton and Barr streets. Her three eldest sons worked as a window dresser, an office clerk, and a barber supplies salesman, hardly the occupations of wealthy princes.

Lula and Frank Butler separated before 1910, which may have prompted Frank to join the South Atlantic League as an umpire in May 1909. Butler made it to the end of June without creating undo controversy, but then the brickbats began to fly in earnest.

After a June 30 game between Macon and Augusta, a columnist for the Macon Telegraph said, “Butler, the umpire, proved clearly that he is incompetent and has no business umpiring in this league.”

A few days later, Butler umped a game between the Savannah Indians and the Chattanooga Lookouts. “Umpire Butler gave general dissatisfaction,” the Chattanooga Daily Times said.

After Butler called Savannah’s Ed Lauzon out on strikes, Lauzon offered a few choice words of criticism. Butler followed the player to his bench and taunted him. It was a bad move by little Butler; Lauzon was a bruiser who worked as a longshoreman in the offseason.

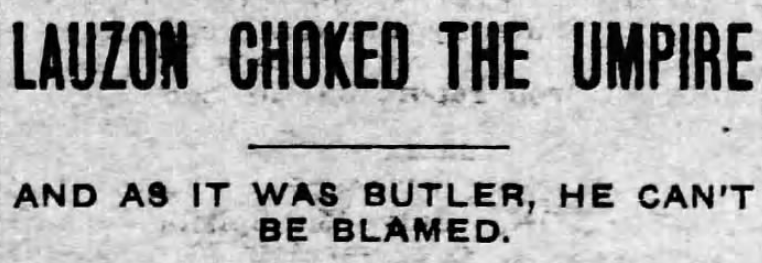

Lauzon turned and grabbed Butler by the throat while the other Savannah players looked on with interest. The Lookouts’ first baseman came to Butler’s aid and separated the ump from Lauzon. The next day, the Macon Telegraph summarized the incident with the headline, LAUZON CHOKED THE UMPIRE – AND AS IT WAS BUTLER, HE CAN’T BE BLAMED.

Macon Telegraph, July 4, 1909.

Macon Telegraph, July 4, 1909.

Ironically, Lauzon went into the umpiring business after his playing career ended and experienced more than his share of abuse. After a game in Moline, Illinois, in 1921, the fans beat Lauzon so severely that he suffered permanent damage to his spine.

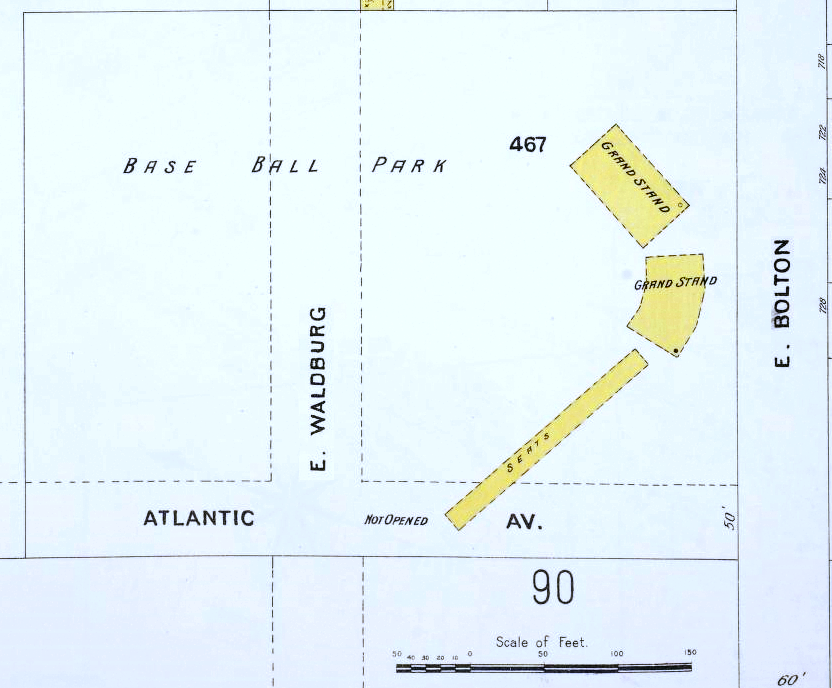

During the following Monday’s Independence Day celebrations, the league assigned Butler to a doubleheader in his hometown between the Indians and the Jacksonville Jays. Bolton Street Park overflowed with fans eager to cheer Shoeless Joe Jackson, their 21-year-old right fielder.

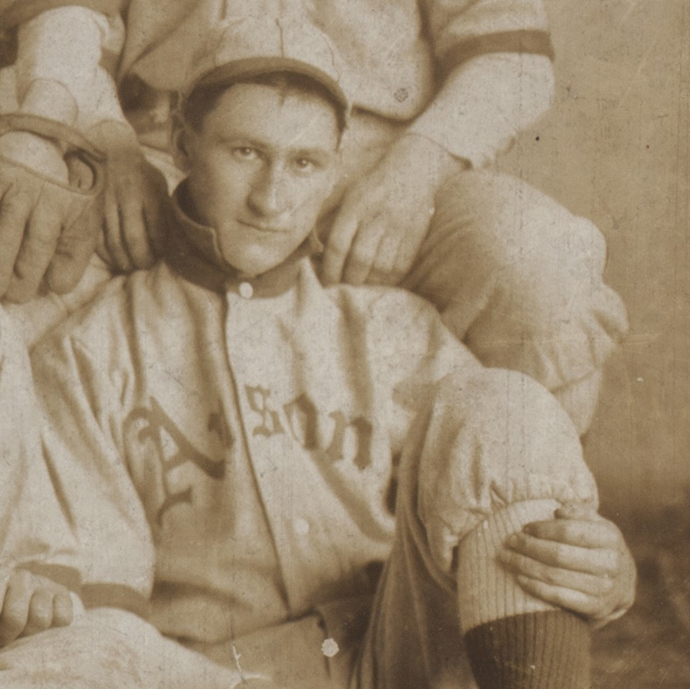

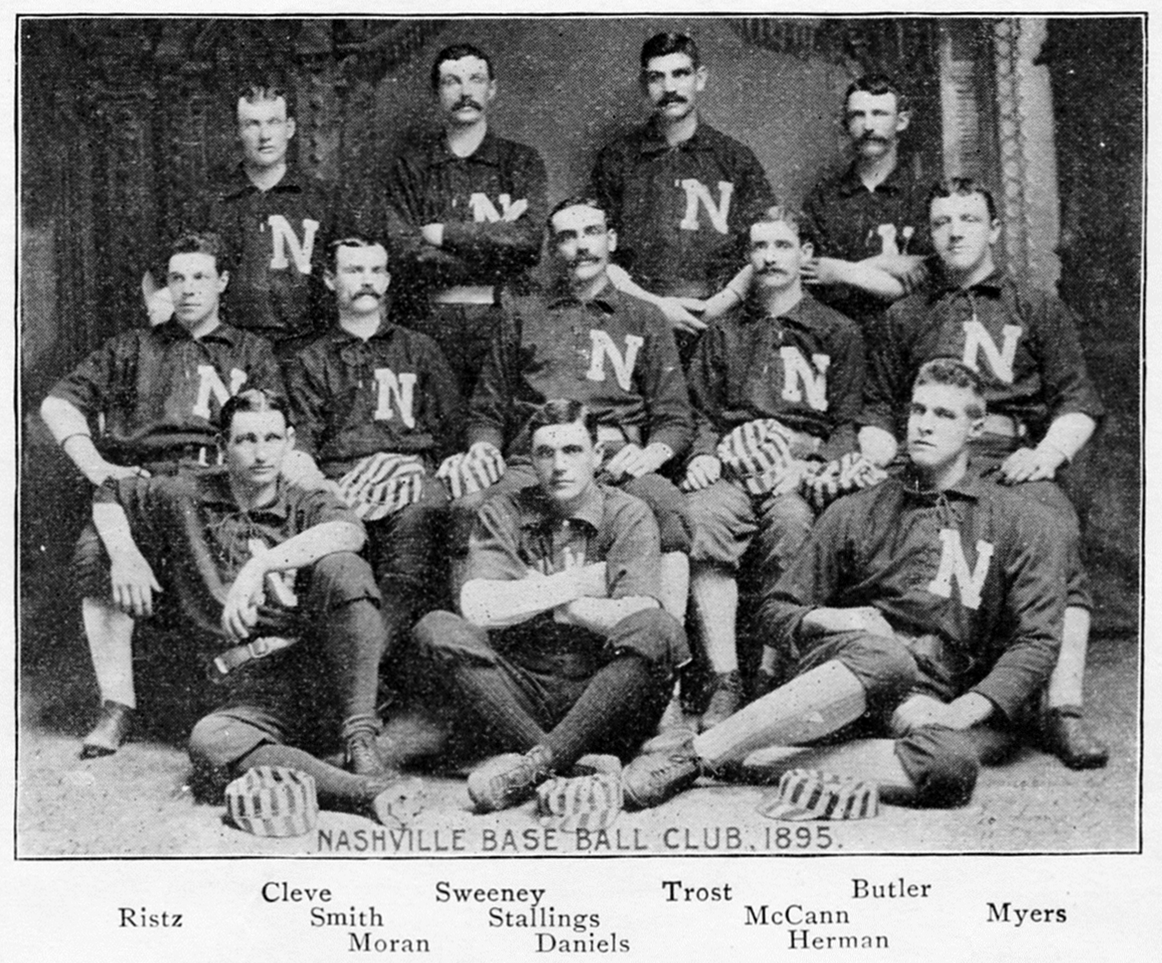

Joe Jackson in Bolton Street Park, 1909.

Joe Jackson in Bolton Street Park, 1909.

Butler’s problems began in the fourth inning of the morning game when he called Jacksonville’s Felton Mitchell safe at third base. “The fans raised objections,” a writer for the Savannah Morning News said, “as Mitchell was caught well off the base, according to everyone but the umpire.”

Bolton Street Park featured grandstands behind home plate and along the first base line, with a narrow section of bleachers extending down the third base line. The unshaded bleachers usually harbored the rowdiest fans and those most likely to be packing a flask. But these fans also had the best view of any action on the left side of the field.

Bolton Street Park, Sanborn Map Company, 1898. North is to the right.

Bolton Street Park, Sanborn Map Company, 1898. North is to the right.

Real trouble arrived in the eighth inning, again on a play by Jacksonville’s Felton Mitchell. With the game tied 1-1 and a runner on second, Mitchell knocked a ball down the third base line. Butler called it a fair ball, and the runner scored to give Jacksonville the lead.

“From the grandstand and bleachers the ball was in every sense of the word a foul, hitting off the line, and bounding into the ground near the bleachers,” the Morning News reported. “The bleachers made vigorous protest, and in less than a minute the fence was broken down and a large number swarmed on the field after Butler.”

A squad of policemen rushed into the fray, holding the belligerents in check. Savannah Mayor George Tiedeman came down from the grandstand and addressed the crowd. He promised that if they returned to their seats, he would ensure Butler did not work the afternoon game. The rioters left the field, but shouts of “mob him” and “do him up” continued for the remainder of the game.

Jacksonville won 3-1. After the final out, a mob rushed onto the field, making a beeline for Butler. The ump headed for an exit, but the crowd cut him off. Six policemen arrived and escorted Butler to the corner of East Broad and Gwinnett – a long walk west on Bolton, then north on East Broad – where he awaited a streetcar.

As Butler cooled his heels in the unpaved street, the crowd around him grew to almost 500 men and boys. “The streets were literally packed from sidewalk to sidewalk and it was with difficulty that the cars were operated,” the Morning News said.

Butler boarded a northbound E&W Beltline streetcar accompanied by two patrolmen and as many cranks as could pack into the car. The fans in the streetcar dubbed it the Butler Special.

The car began to inch down East Broad, escorted by two mounted patrolmen. Someone on the rear platform set the brakes. When the conductor moved to release them, another crank reached onto the roof and disconnected the trolley from the overhead wires. Repeating the stunt impeded the car’s progress, allowing the mob on foot to keep up.

When the streetcar reached the Tybee station, a police car bearing a pair of detectives pulled alongside, and the officers bundled Butler into the back. The detectives drove Butler to his home at Drayton and Gordon Lane as the rioters tried to keep up.

“When Butler alighted he was again surrounded by a crowd,” the Morning News said. “There was nothing done, however, though quite a lot of talk was hurled at the umpire. He remained cool and collected throughout the trouble, and kicked against leaving the streetcar for the police auto, saying that there was no use in doing this.”

“For a man born and raised in Savannah, I was certainly given a shabby deal,” he said. “I was not afraid of a person in the crowd, and was willing to leave and go home without the police.”

And regarding Mitchell’s hit down the line in front of the bleachers, Butler said, “If ever there was a fair ball hit on the Savannah diamond, the one the crowd kicked on was fair. I stick to it that the ball hit down the third base line in the eighth was fair, and I have had hundreds to tell me the same thing.”

The tormentors outside Butler’s home eventually gave up and returned to the ballpark for the afternoon game. Hank Matthewson, the brother of pitcher Christy Matthewson, held the indicator. Although officially a member of the Jacksonville pitching staff, Matthewson sometimes picked up a few extra dollars by working as a substitute umpire.

Jacksonville won, 4-2. As the fans filed from Bolton Street Park, they sang, to the tune of “I Love, I Love, I Love My Wife – But Oh You Kid,” a popular song recorded by Billy Murray in 1909, We like, we like, we like our ball team, but oh you Butler!

The South Atlantic League discharged Butler, and he followed Con Lucid north to the Carolina Association. His employment there was briefer than his five-game stint with the Giants in 1895.

The league assigned Butler to work a four-game series between the Charlotte Hornets and the Spartanburg Musicians in Charlotte’s Latta Park. The first game, taken by the visitors on July 8, passed without incident. The Charlotte Observer said, “Mr. Butler officiated and gave general satisfaction.”

Butler failed to impress the Charlotte Evening News. The paper called Butler a “South Atlantic cast-off” and said, “The ump’s voice was about as small as he was himself. ‘His voice reminded me of a katydid,’ said a fan after the game.”

Henry Schulz, six-foot-three and 185 pounds, took the mound for the Hornets. Referring to the umpire working behind the pitcher with men on base, the Evening Chronicle said, “It was a comical sight to witness Big Heine Schulz on the mound and Diminutive Umps behind him.”

The “general satisfaction” with Butler disappeared the following day as the Hornets took both games of the doubleheader.

“The umpiring of Butler came near sapping a lot of interest out of both games, the two teams protesting with good cause on some of his decisions. His observation of balls and strikes reached the ridiculous point. While he made many rank rulings against the home club, the visitors were not exempt from his miserable mistakes,” the Charlotte Observer said. “The umpire’s lamps were not burning at all brightly yesterday.”

Fixating on Butler’s small voice, the Evening Chronicle said, “You could hear the umpire way down in the valley calling balls and strikes, and how I did wish he would come up in the diamond with his voice.”

Butler’s car came completely off the rails in the series’ final game. The ump made several bad calls, though his decisions broke against both sides. The Charlotte Observer bluntly summarized Butler’s performance: “Never in this city has there been such a demonstration of rotten umpiring.”

The Hornets jumped out to an early 3-0 lead, but the Musicians bounced back and climbed on top, 4-3, in the top of the eighth. In the bottom of the inning, with Hornets on second and third, the Charlotte batter sent an easy fly to Spartanburg left fielder Fred Springs.

Springs muffed the catch, the runner on third scampered home to tie the game, and the man on second, after tagging up, took off for third. Springs recovered the ball and fired it to the third baseman to catch the sliding runner. Butler, working behind Spartanburg pitcher Tom Abercrombie, called Safe! on a close play.

Abercrombie retrieved the ball and complained loudly. Butler responded by fining the pitcher $5. Abercrombie suddenly fired a fastball at Butler’s head. Butler was only two feet from Abercrombie, but the pitch went wide of the mark. Abercrombie, six feet tall and 175 pounds, leaped upon Butler, flung the little ump to the ground, held him there, and administered a proper beating.

The Spartanburg fielders simply watched. “The Spartanburg players were not hurrying to the defense of the umpire when he was so viciously attacked,” the Observer reported. “A number of the visiting players stood by and watched the assault as if they were glad it had been instituted by the pitcher.”

Charlotte third baseman Fred Linneborn ran onto the field and tried to pull Abercrombie away from Butler. Fred Springs entered the fight from left field, grabbing Linneborn and throwing him to the ground. The Charlotte bench emptied, and the melee became a general affair. The fans ripped apart the wire netting that fronted the grandstand and swarmed the field.

Twenty minutes elapsed before the police restored order. The officers led Abercrombie out of Latta Park and sent him off in a streetcar. The game resumed; Charlotte broke the tie in the last inning and won 5-4.

Though Abercrombie had left the game a free man, Recorder D.B. Smith charged him with assault and issued a warrant for his arrest. Abercrombie appeared in court that night at 8 o’clock.

Smith summoned Butler as a witness. Before testimony began, Butler stepped to the rail and asked Smith to dismiss the case. According to the Observer, Butler maintained that “such things were not infrequent in baseball and that he did not wish to see the young player punished.”

“Well, we attend to assaults down here,” Smith responded, and he demanded that Butler testify.

On the stand, Butler denied that any assault had taken place. Butler said that he and Abercrombie had fallen, that he did not know if he was struck or not, and that his body bore no evidence of being hit.

Abercrombie took the stand and blamed it all on Butler. He said he hurled the ball at Butler after the ump uttered a profanity. That part was possibly true, given Butler’s earlier taunting of Lauzon that led to his strangulation.

Butler apparently possessed the ability to get under a victim’s skin in that most infuriating way that inspires an otherwise reasonable person to commit acts of violence on a physically weaker antagonist. Butler may have been a passive-aggressive bully, absorbing some physical retribution in exchange for experiencing the pleasure of seeing the court punish or humiliate Abercrombie.

Abercrombie said that Butler had grabbed him first, that he threw Butler to the ground in self-defense, and that he had not struck Butler. In Abercrombie’s mind, this may have been a fair representation of the emotional tangle between pitcher and umpire.

“You needn’t try to defend your act,” Recorder Smith replied, “and there is no need of introducing further testimony on your behalf. I was in the grandstand and saw the entire transaction. I saw you throw the ball at him and after getting him on the ground, pummel him. I’ll fine you $25 and the costs, and I want to say that the next time a baseball player undertakes to make brutality out of a sport for which people pay to see, he will receive a sentence of 30 days on the roads. Such an exhibition before 1200 people, many of them ladies, was disgraceful, and it won’t go unpunished here.”

Carolina Association President J.H. Wearn, who attended the game and witnessed the attack, fined Abercrombie $50. Then he fired Butler, ending the umpire’s Carolina Association tenure at four games. Reporting on the Charlotte incident, the ever-spiteful Macon Telegraph closed the book on Butler’s umpiring career: “Butler is one of the biggest jokes as an umpire that this league has ever known.”

Frank Butler moved to Jacksonville, Florida, remarried, and worked as a bill collector for a furniture store and the Florida Times-Union newspaper. He died in 1945.

Charles F. Leibrich, Jr. was a rarity among minor league umpires: he was popular with the fans.

Leibrich grew up in Titusville, Pennsylvania, where Colonel Edwin Drake discovered oil in 1859, inaugurating the US oil industry. Leibrich worked in the oil fields as a pumper and mechanic.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Leibrich enlisted with the 16th Pennsylvania Infantry. He joined Company K on April 27, trained at Georgia’s Camp Chickamauga, participated in the Puerto Rico campaign, and mustered out as a corporal on December 29.

Returning to Titusville, Leibrich became a boxer, fighting as Kid Leibrich. Standing five-foot-nine and weighing between 130 and 145 pounds, he recorded four wins and two losses. Newspaper accounts suggest Leibrich fought several more bouts that the official records do not recognize.

Leibrich fought Joe Leonard, a respected lightweight, in early 1901. Police halted the bout after Leonard sent Leibrich to the canvas seven times in three rounds. The referee declared the fight a draw since the police broke it up before he could officially declare Leonard the winner. “Leibrich is a tough boy and a hard hitter,” Leonard said afterward. “He took a good beating and got away with a lucky draw.”

Later that year, Leibrich, then 23, was arrested and charged with assault after he shot a youngster through the foot with a .22 rifle. Leibrich claimed he had been shooting at a sparrow. A jury found him not guilty but charged him $80 in court costs for carelessly handling his gun.

Leibrich began umpiring semi-pro ballgames around Titusville in the early 1900s. By 1906, he was the best umpire in the region. The Titusville Herald said, “Mr. Leibrich has all the qualifications of an umpire, including voice, judgment, and determination. He is quick in his decisions and almost invariably right. He does not frighten easily and bulldozing is something for which he will not stand.”

The Class C Virginia League hired Leibrich in 1907. Umpiring a late-season game in Richmond without a chest protector, he was struck over the heart by a foul tip. In the words of the Richmond Times-Dispatch, Leibrich “fell like a dead man.” Two doctors rushed to his aid, but Leibrich lay unconscious for 10 minutes. He finally rose, completed the game, and felt well enough to eject an argumentative player from the park.

The Virginia League sought Leibrich’s services again in 1908, but he chose to stay in Pennsylvania, where he umpired high school and semi-pro games.

Leibrich appeared in the Carolina Association in June of 1909. The newspapers around the circuit usually spelled his name Liebrich.

Though no longer a 130-pound lightweight, he was small enough to be described by the Charlotte Observer as “that plucky little fellow.” On a close play at a base, he would bend deeply at the knees like a sideshow acrobat, bringing his body near the ground.

Leibrich maintained an exaggerated Prussian manner, an effect accentuated by his perfectly bald head. The Charlotte Evening Chronicle said, “Mr. Leibrich’s military bearing is never so pronounced during the slaughter than when he points his finger between the eyes of a Hornet, who has just tried to slide home, as if it (his finger) were a Krag-Jorgensen [the standard US rifle during the Spanish-American War], and announces in martial tones: ‘You are out!’”

His popularity was rooted in his ability to amuse the fans. After a rather dull game in Winston-Salem, the local Journal said, “The game was interesting chiefly on account of the ump’s histrionic ability. Leibrich is a swell comedian, and the game was a farce giving him ample opportunity to give expression to much that amused the crowd.”

Part of Leibrich’s act involved accepting the fan’s abuse. A writer for the Winston-Salem Western Sentinel said, “When we call him a robber, a muttonhead and such other names that fittingly become an umpire, he casts his beaming countenance toward us and we feel like thirty cents.”

“If my friends don’t cuss me at a ball game, then I can’t sleep good at night,” Leibrich told the writer, “for I know that cussing the umpire is one of the most pleasing features of the game to the bugs, and when they fail to yell and holler at me then I know the game is not worth the price.”

Leibrich sometimes corrected a missed call, a practice abhorred by virtually every other person who has ever held the indicator. And though his style leaned to the theatrical, he was quick to throw a fine on any player who delayed the game with a too-lengthy argument. “Umpire Leibrich is the monarch of the diamond and he rules with an iron hand,” the Western Sentinel reported. “He takes no foolishness from the players and keeps the game going.”

But Leibrich failed to impress every critic. After an Independence Day game in Greensboro, the Greensboro News called Leibrich out for his “clownish stunts.” The News said, “If Leibrich would pay a little more attention to balls and strikes when umpiring games here he would come much nearer making a hit with the stands than by the unnatural contortions he worked his face into yesterday.”

And the Charlotte Observer, while praising Leibrich’s ability to run the game and see the entire field, called the ump “a somewhat ridiculous character.”

Leibrich had an amusing and entertaining way of dodging foul balls. But in the fourth inning of a July 2, 1909, game in Winston-Salem, he failed to avoid the ball and caught a terrific blow to his chest. Just as he had in the Virginia League two seasons before, Leibrich went down for the count.

“The lick was sufficient to put His Umps to sleep for several minutes,” the Western Sentinel reported, “and the crowd thought it had a dead umpire on its hands.” Leibrich was carried off the field, and two players took over the umpiring duties.

He emerged from the clubhouse in the eighth inning, and the crowd greeted him with enthusiastic cheers as he took his place on the diamond. After the game, Leibrich was seen in a nearby drugstore buying a bottle of liniment.

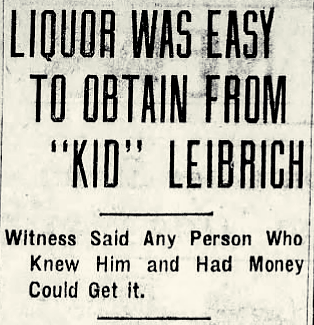

Charles F. Leibrich umpired in the Carolina Association in 1909 and 1911. In 1916, he opened a pool hall in Oil City, Pennsylvania. He was arrested for selling liquor without a license in 1918 but escaped custody and was on the lam for almost a year. Finally captured, Leibrich was sentenced to eight months in the workhouse but was released on parole after serving 79 days. A few weeks later, Leibrich was back in Oil City umpiring a semi-pro baseball game. Charles Leibrich died in 1952 in Huntington Park, California, where he worked as a crossing guard.

Franklin Evening News, April 24, 1918.

Franklin Evening News, April 24, 1918.