Charles Durmeyer, the Cotton States Baby

Charles Philip Durmeyer, Jr. was born in New Orleans on August 29, 1889. His father, Charles Durmeyer, Sr., was a butcher with a few seasons of minor league ball to his credit. Charles Sr. gave up the professional game when his son was born but continued to play semi-pro baseball. He was one of the best second basemen in New Orleans.

Charles Philip Durmeyer, Jr. was born in New Orleans on August 29, 1889. His father, Charles Durmeyer, Sr., was a butcher with a few seasons of minor league ball to his credit. Charles Sr. gave up the professional game when his son was born but continued to play semi-pro baseball. He was one of the best second basemen in New Orleans.

Charles Jr. grew up on the sandy ballyards of the Crescent City. He joined his father on the semi-pro diamond when he was 15, usually playing third base.

In the spring of 1906, young Durmeyer, now 16, entered the professional ranks with the Baton Rouge Cajuns of the Class D Cotton States League. The team took him on a pre-season road trip to Texas, but Durmeyer failed to stick. By mid-April, he was with a semi-pro team in Alexandria, Louisiana.

Baldomaro Carbo, a paving contractor, owned the Alexandria club. He hailed from New Orleans and may have known Durmeyer or his father. Carbo was a bit of a showman – he signed a one-armed pitcher in 1908 – and may have recruited Durmeyer for his novelty appeal. The youngster was an immediate hit in Alexandria. Sportswriters dubbed him The Candy Kid.

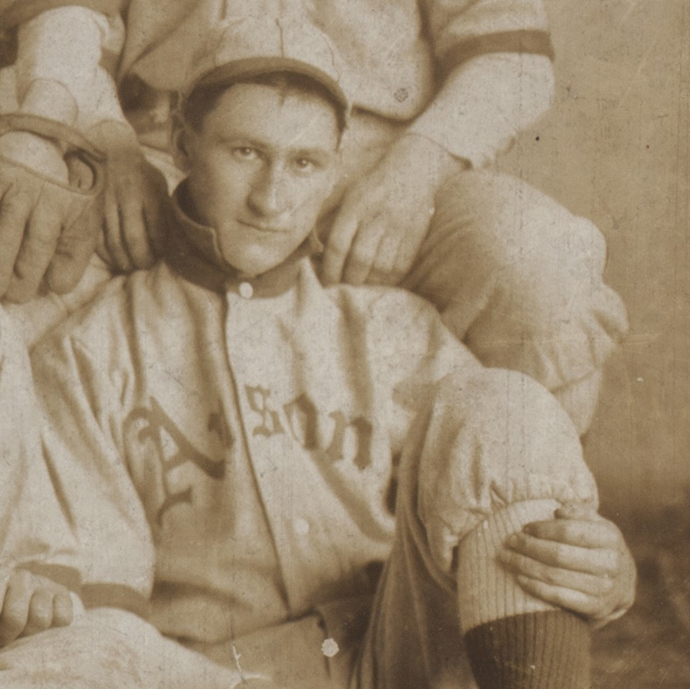

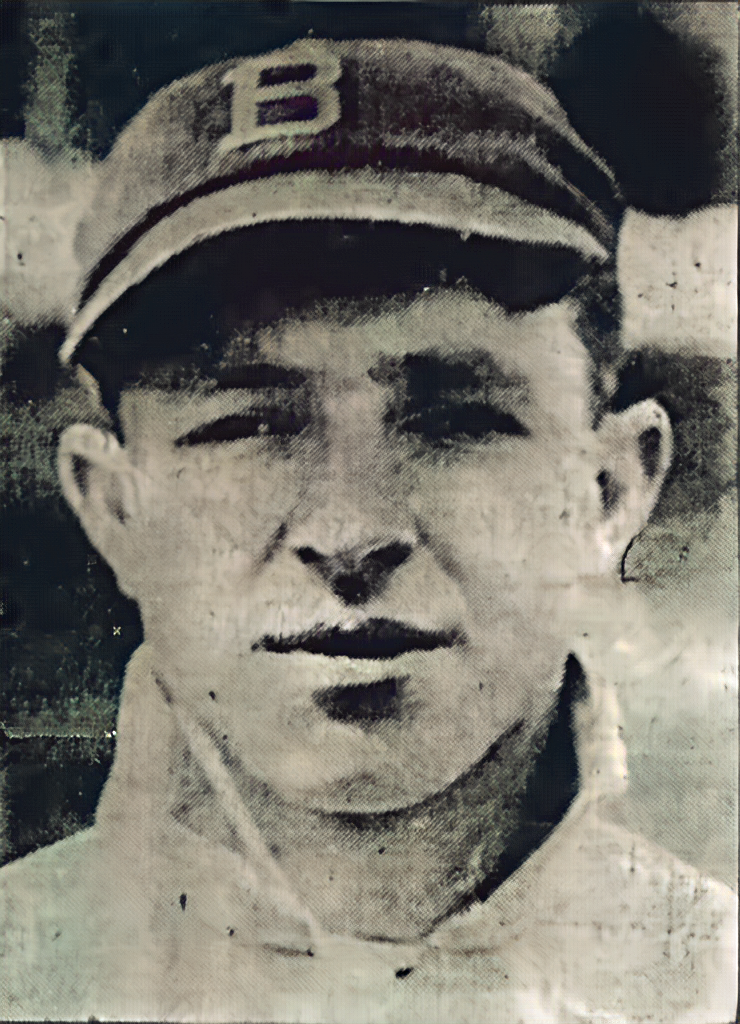

Charles Durmeyer, Jr. Buffalo Times, May 3, 1909.

Charles Durmeyer, Jr. Buffalo Times, May 3, 1909.

A few weeks after arriving in Alexandria, Durmeyer and three other ballplayers took a quartet of young ladies on a crayfish hunting expedition. Though the town is on the banks of the Red River, the players favored a location three miles away. After walking there with their dates, the enterprising players realized they had “forgotten” the bait. “They spent the evening picking wild flowers in the pinewoods,” the Alexandria Town Talk said.

Semi-pro players in a small southern town made little money, and most had regular jobs. To make ends meet, Durmeyer, still only 16, worked as the night clerk in Alexandria’s Stag Hotel.

Durmeyer had probably arrived in Alexandria with very little except his baseball gear. When the team played a three-game stand against Jeanrette, Sackman Bros. Department Store offered a pair of shoes for the series’ first home run. Durmeyer made a mighty effort to win them.

“Durmeyer, ‘the candy kid,’ who no doubt needs a pair worse than anyone else, tried hard for them, making three drives hit the fence,” the Town Talk said. “The Kid says ‘Et’s gist my luck; I bet you I get the next pair.’” Besides the semi-colon, it was undoubtedly an accurate transcription of the Kid’s speech.

Though he played well in Alexandria, Durmeyer was unhappy and left the team in early June. “He has been dissatisfied for some time, claiming he did not like Alexandria,” the Town Talk reported. He told the sportswriter he would play for a semi-pro team in New Roads, Louisiana, a town on the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge. “More money was offered, and then I will be closer to home,” Durmeyer said, suggesting that homesickness may have influenced the 16-year-old’s decision.

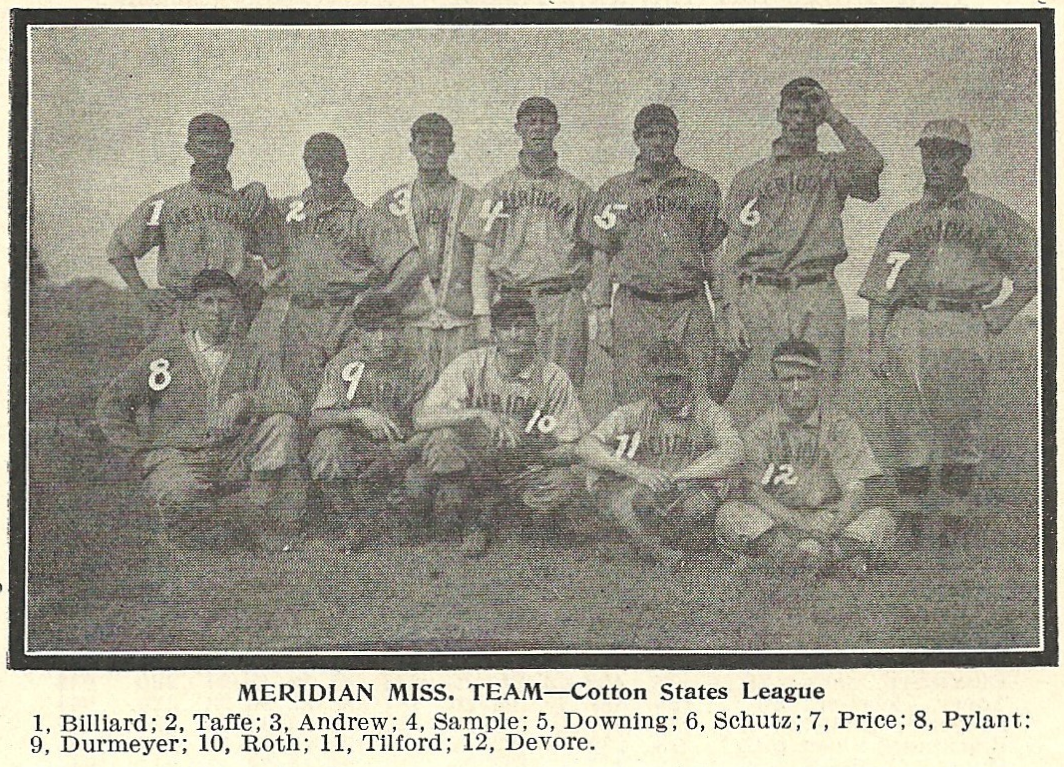

A month later, Durmeyer turned up playing third base for the Cotton States League’s Meridian White Ribboners. He was once more in the fully professional ranks, probably earning about $90 monthly.

His infield work earned praise from writers around the circuit.

“Durmeyer, the kid who is covering third base for the Meridian team, seems to have made good,” the Vicksburg Evening Post said in mid-July. “Durmeyer is young and small. He is fleet and nimble and his fielding sharp and snappy. He generally knows what to do with a ball when he gets it.”

Durmeyer’s father was a small man, and Charles Jr. inherited his stature. Until late in his playing career, sportswriters called him “little Durmeyer.” His World War I draft registration recorded his height as Short. His draft registration for the next war shows a precisely-measured height of five feet five-and-one-half inches. The registrations also tell us that Durmeyer had a light complexion, brown hair, and brown eyes.

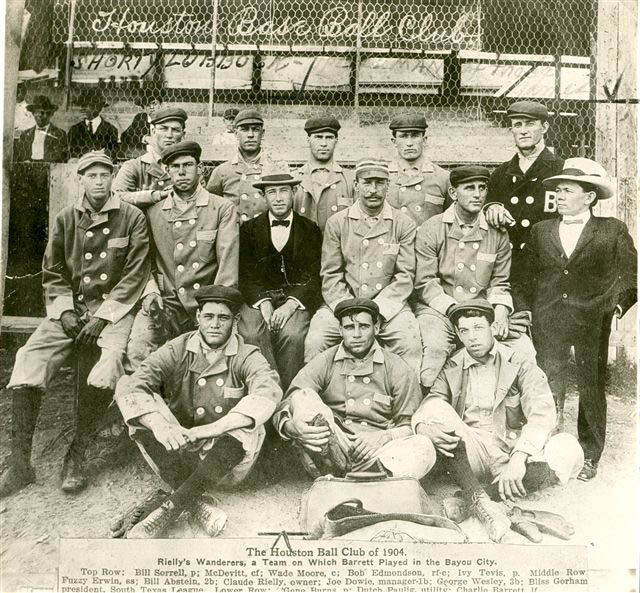

Durmeyer (9) with the Meridian Ribboners, 1907.

Durmeyer (9) with the Meridian Ribboners, 1907.

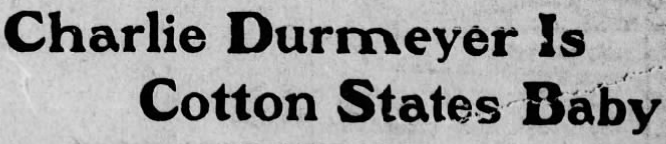

Durmeyer played two seasons with Meridian, then signed with the Cotton States League’s Columbus Discoverers in 1908. Usually playing shortstop, Durmeyer appeared in 119 of the Discoverers’ 120 games. He missed a Sunday game when he returned to New Orleans for a family member’s baptism.

Eighteen years old when the 1908 season opened, Durmeyer was still the youngest player in the league, earning him the title of The Cotton States Baby.

Headline in the Vicksburg Evening Post, July 4, 1908.

Headline in the Vicksburg Evening Post, July 4, 1908.

An article about the Baby appeared in the Vicksburg Evening Post on Independence Day. The feature revealed a pleasant young man who loved the rough-and-tumble life of a Class D minor leaguer:

“Durmeyer remains a boy in appearance and tastes. ‘Do I like to play ball?’ he repeated when asked this question. “Why there’s nothing in the world I like better. I wouldn’t stay out of the game for anything. It’s my ambition to be a great player. There’s a lot of things I like about the life of a ball player. I always like to see the first and fifteenth of the month roll around – those are pay days. I never made so much in my life before as I am making now playing ball. I enjoy traveling around and the girls in the different Cotton States cities are too sweet for anything. You better not say anything about that, though, for after all there’s no one like a certain little person in New Orleans that I know.’”

In those days, umpires were allowed to fine players on the spot for crabbing, arguing, or doing anything that slowed down the game. Tariffs usually began at $5 and escalated until the player gave up or suffered ejection. A squad of policemen stood ready to remove players who refused to submit. Some players were habitual kickers, and some umpires were notoriously quick with the fine and the hook. The Evening Post article described Durmeyer’s view on fines:

“Durmeyer is a popular little player around the circuit. He is a hard and earnest worker, but he never baits an umpire. He thinks it is bad policy and thinks he needs the money more than the league treasury, so he doesn’t run the risk of an umpiratical fine. Durmeyer has never been fined or put out of a game, he says, since he joined the league. He sometimes kids an umpire, if he thinks the indicator is a good-natured man, says the ‘Kid.’”

Durmeyer (4) with the Columbus Discoverers, 1908.

Durmeyer (4) with the Columbus Discoverers, 1908.

The Discoverers went through four player-managers in 1908. On July 8, Lou Hall became the fourth and final man to fill out the Columbus lineup card. Hall was a big man with a well-deserved reputation for being a blowhard. Soon after arriving in Columbus, he gave reporters a story about Durmeyer’s early days in Meridian two seasons before:

“When Durmeyer first went to Meridian and became one of the notables of that city, he followed the bent of his ways and was soon mixing with the fair sex. Only a short time elapsed before he received an invitation to attend a swell dance. Durmeyer didn’t know exactly how to prepare for this affair, and taking aside one of the ball players asked for a kindly tip. ‘It don’t make much difference what else you wear,’ said the ball player with an earnest face, ‘but for the Lord’s sake don’t forget your gloves. Be sure to wear gloves.’

“When the night of the ball rolled around Durmeyer appeared at the scene of the festivities with a valise in his hand. ‘Why, where are your gloves,’ asked one of his friends at the door, who had been warned to look out for Durmeyer’s personal appearance. ‘I have them in my valise,’ replied Charlie, and going into an ante room, he remained a few minutes.

“When he returned, he had assumed a pouter pigeon aspect, and said: ‘Now show me the ball room.’ Charlie had a catcher’s mitt on his right hand and a fielder’s glove on his left flipper. A number of Meridian players will vouch for the story.”

The tale appeared in newspapers all around the Cotton States League. It may have been true, given that the young man was only 16 when he arrived in Meridian and had previously required a home run to get a decent pair of shoes on his feet. But why Hall wished to embarrass his player and how Durmeyer reacted to the story were not recorded.

Durmeyer in spring training with the Buffalo Bisons. Buffalo Morning News, April 11, 1909.

Durmeyer in spring training with the Buffalo Bisons. Buffalo Morning News, April 11, 1909.

In 1909, Durmeyer signed with the Buffalo Bisons of the Class A Eastern League, a major jump into fast company. He was unprepared for the competition and the climate.

The Bisons’ spring training began on March 29 in Joplin, Missouri – probably the farthest north the youngster had ever journeyed. He caught a cold on the train ride from New Orleans and could not take the field. In late April, with the team now in Buffalo, he was reported to be “battling with brother grippe and had the worst of the encounter.”

A team photograph taken during spring training shows Durmeyer looking well-dressed in a suit and tie and wearing nice shoes. Five months shy of 20, he appears to have overcome the lack of sophistication that marked his first year of professional ball.

Durmeyer (fourth from right) with the Buffalo Bisons. Buffalo Courier, April 13, 1909.

Durmeyer (fourth from right) with the Buffalo Bisons. Buffalo Courier, April 13, 1909.

Durmeyer saw limited pre-season playing time with the Bisons and failed to hit when given a chance; the club sent him to the Wilkes-Barre Barons of the Class B New York State League. “Durmeyer as a fielder was one of the brightest stars seen here in some time but he was weak at the bat,” The Buffalo Enquirer explained.

Durmeyer spent four seasons in Pennsylvania playing shortstop for Wilkes-Barre in 1909 and for Altoona of the Class B Tri-State League from 1910 through 1912. He was known as Kid Durmeyer or The Kid.

Durmeyer married Louise Carrie Denny before the 1910 season. Their first child, Charles Denny Durmeyer, was born in New Orleans on May 1, 1911. While awaiting the event, Durmeyer missed Altoona’s spring training. The club’s management labeled Durmeyer a holdout and threatened him with suspension. He left New Orleans immediately after his son’s birth and, though absent from the opening day game, was on the field for their second game, played May 4.

Charles and Louise had three more children: Louise Muriel (1913), Evelyn Mae (1916), and Lloyd (1922).

Before 1916, Durmeyer’s legal name was Greininger. Charles Sr.’s father was Ignatz Greininger, a New Orleans laborer possibly known as Carl. Greininger died while Charles Sr. was an infant. Two years later, his mother, Mary Anna, married Christian Durmeyer, a vegetable peddler who raised the boy as his own. Charles Sr. grew up using the Durmeyer name. In 1916, Charles Sr. and his sons, Charles Jr. and August, petitioned to have their names legally changed to Durmeyer.

Durmeyer retired from baseball following the 1912 season and joined his father in the meat trade. “He is engaged in the butchering business in New Orleans and is doing so well that he has decided to give up the professional game,” the York Dispatch reported in December 1912. “Charlie has played professional ball for seven years and he saved his earnings and last fall purchased a large establishment.”

In a letter to the Reading Eagle, Durmeyer said, “I guess I have played my last professional game. I’m doing great in the butcher business and will stick to it and play with independent teams around home.”

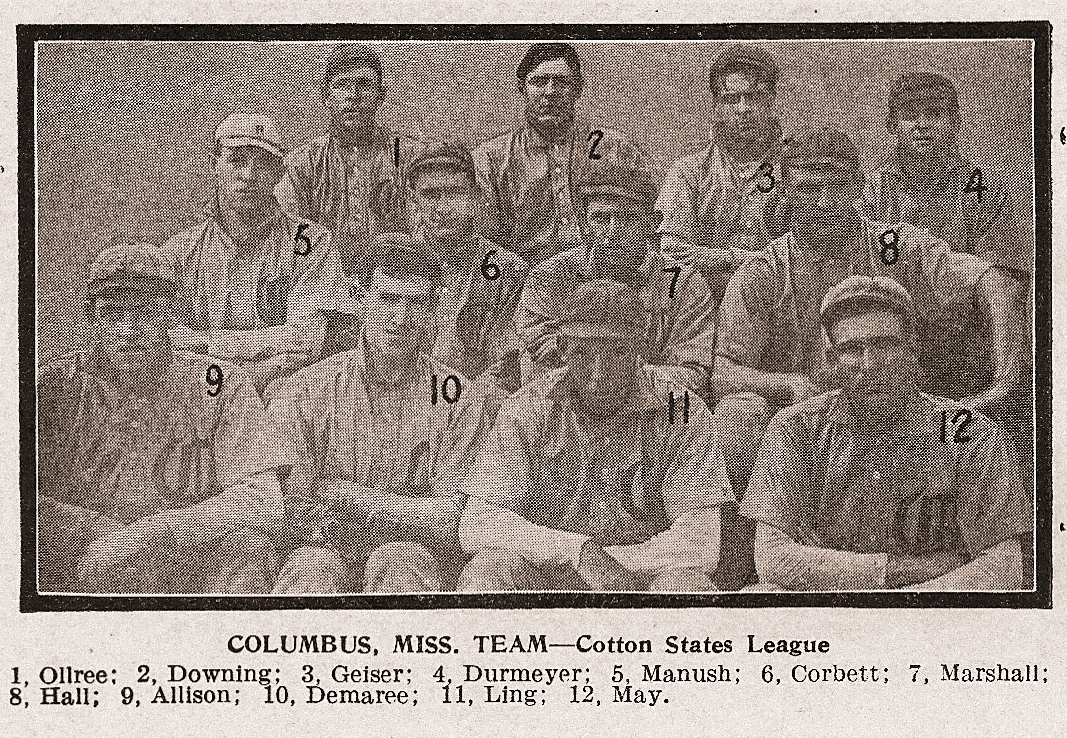

Durmeyer (7) with the Charleston Sea Gulls, 1914.

Durmeyer (7) with the Charleston Sea Gulls, 1914.

His retirement proved short-lived. Released by Altoona, he signed with Meridian, his old Cotton States team, in 1913, then moved up to the Albany, Georgia, club of the Class C South Atlantic (Sally) League. He split his final season, 1914, between Albany and the Sally League’s Charleston club. He retired for good at age 25 having played minor league ball in parts of nine seasons.

Durmeyer worked as a butcher for the remainder of his life, running a shop inside the Ewing Market at the corner of Magazine and Octavia streets.

Ewing Market, New Orleans, 1941.

Ewing Market, New Orleans, 1941.

Charles Philip Durmeyer, Jr., the former Cotton States Baby, died on May 18, 1959, at age 69. His grave is in New Orleans’ Metairie Cemetery.

Durmeyer family graves, Metairie Cemetery, New Orleans. From findagrave.com.

Durmeyer family graves, Metairie Cemetery, New Orleans. From findagrave.com.