The South

And is there anything that can tell more about an American summer than, say, the smell of the wooden bleachers in a small-town baseball park, that resinous, sultry, and exciting smell of old dry wood.

– Thomas Wolfe, letter to Arthur Mann, 1938

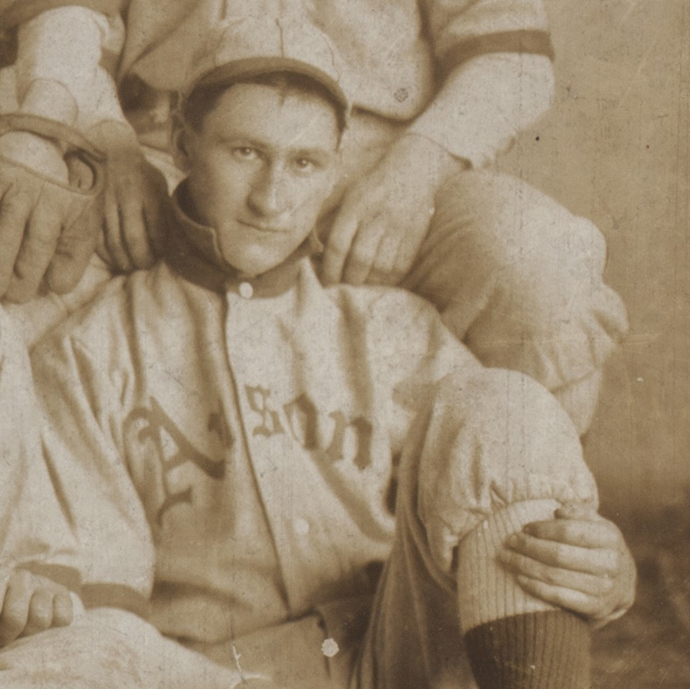

Captain W.T. Crawford was one of the most prosperous businessmen in northwest Louisiana, with interests in banking, insurance, railways, and cotton trading. His title was a remnant of his days as commander of the Shreveport home guard. In late 1907, Captain Crawford found himself in the unenviable position of owning two minor league baseball teams.

Since 1902, Crawford had been the majority owner of the Class A Southern Association’s Shreveport Pirates. But Shreveport was a small, isolated market. The gate receipts often failed to cover a visiting team’s guarantee, and teams journeying to Shreveport from the league’s eastern realm sometimes arrived too late to begin play.

Following the 1907 season, Crawford endeavored to reduce his operating expenses by downgrading to a lower minor league. He purchased the Class C Texas League’s Temple franchise and moved it to Shreveport, then sold his Southern Association franchise to a group of businessmen in Mobile, Alabama. The Shreveport team retained the Pirates name. The Mobile team became the Sea Gulls.

Delays in finalizing the sale to the Mobile group resulted in Captain Crawford owning, in December 1907, both the Texas League and the Southern Association teams, with both officially located in Shreveport. Crawford assigned Tom Fisher, player-manager of the former Pirates, the task of assembling rosters for both franchises.

Fisher was a big redhead, born, raised, and destined to die in Anderson, Indiana. He was a reliable Class A pitcher, compiling a 160-122 record over 11 minor league seasons. Like most minor league player-managers, Fisher had some major league experience: 39 games with the National League’s Boston Beaneaters in 1904.

Tom’s older brother, Chauncey, pitched parts of five seasons in the majors, enjoying his best year in 1896 when he was 10-7 with the Cincinnati Reds.

Their younger brother, Robert W. “Bob” Fisher, played outfield for the Class D Coffeyville, Kansas team in ’06 and ’07. Baseball historians have confused Robert W. Fisher with Robert A. Fisher, a first baseman who played for the Argenta Shamrocks in 1908. Released from Argenta after uttering a vulgarity overheard by ladies in the grandstand, he later played for Kewanee, Jacksonville, and Columbia.

On November 17, 1907, the Muncie Star Press reported that Tom Fisher, Bob Fisher, and Jack Corbett were all enjoying a vacation in Anderson. By the year’s close, Tom had signed Corbett and Brother Bob to play for Shreveport’s Class C club.

Tom Fisher eventually landed in Mobile, where he managed the Sea Gulls. Captain Crawford hired Dale Gear to manage the Pirates. Gear was a 36-year-old pitcher and outfielder with 69 major league games to his credit. The Shreveport Times described him as “a quiet, unassuming young athlete, neat and gentlemanly, such a man as Captain Crawford wants for a leader, and a versatile ball player.”

On February 16, 1908, the Times reported, “A contract has been sent to Corbett, a second baseman, and a fast man in all departments, it is said.” The team wired Corbett his train tickets on March 16.

Corbett and Bob Fisher left Anderson on the last day of winter. Temperatures were near freezing when they boarded a Central Indiana Railway car bound for Cincinnati. From there, they traveled south through Kentucky and Tennessee to Chattanooga, southwest across Alabama to Meridian, Mississippi, then due west through the bare cotton fields. They crossed the big river at Vicksburg, then rode across northern Louisiana almost to the Texas border. After traveling well over twenty-four hours, Corbett and Fisher arrived in Shreveport, a town of about 25,000 souls on the Red River, and stepped from the car into “fair and cold” weather with temperatures in the mid-50s.

Corbet was 20 years old. The ambitious dreams of stardom fostered by his season in Chicago were challenged before the season drew to a close in the heat of a Mississippi summer.

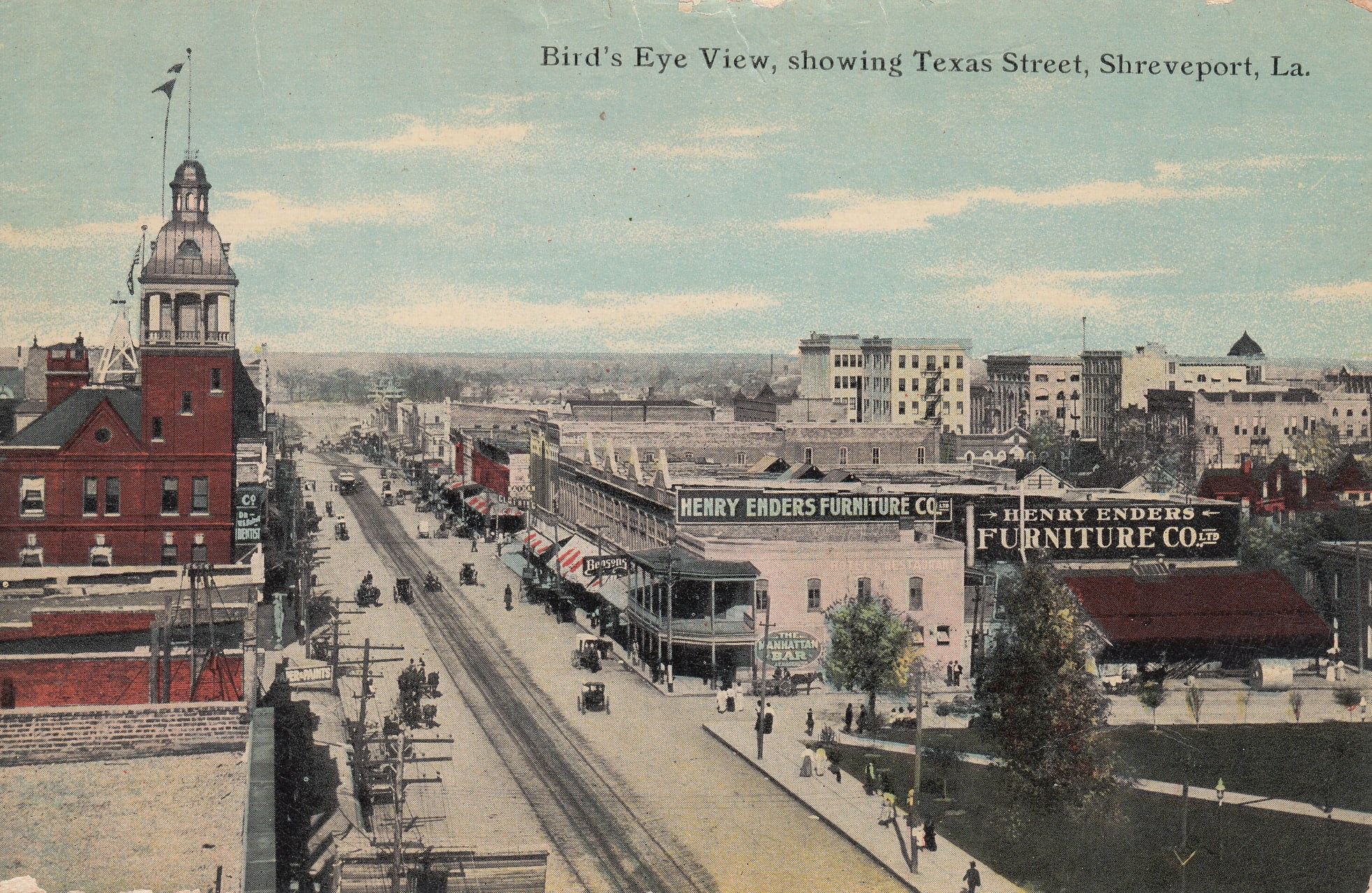

Texas Street, Shreveport, Louisiana, circa 1908.

Texas Street, Shreveport, Louisiana, circa 1908.

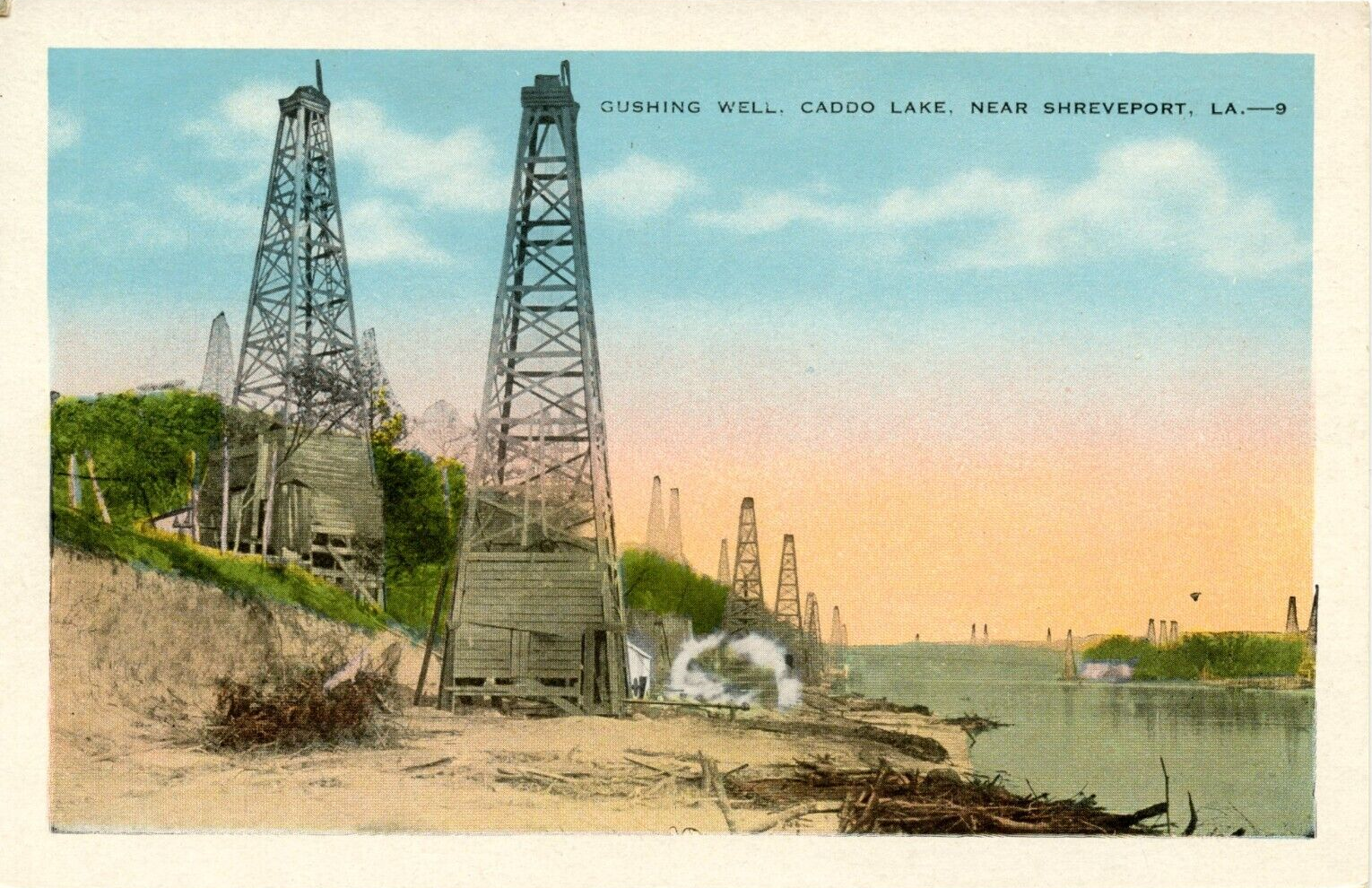

Thirty-seven years before Jack Corbett came to northwest Louisiana, a night watchman noticed gas seeping from a water well drilled by the Shreveport Ice and Refrigerating Company. The slow bubbling revealed the Caddo Field, a large oil and gas accumulation, and initiated the Louisiana petroleum industry. Louisiana’s first natural gas pipeline, connecting the Caddo Field and Shreveport, opened in 1908.

Caddo Field near Shreveport, Louisiana.

Caddo Field near Shreveport, Louisiana.

Manager Gear divided the Pirates into two squads. The projected starters, including Corbett at second base and Bob Fisher in left field, became the Gassers. The second-stringers were the Oilers. The hierarchy reflected the layers of oil and gas in a hydrocarbon accumulation: gas floats above oil in a field that contains both phases.

Rain prevented complete workouts until Tuesday, March 24. Corbett’s work at second base made a good first impression on the locals who skipped off work to find a sunny spot in League Park and enjoy the 71-degree spring weather: “Petit, Erwin, Arnold, Corbett and Thebo have already won homes in the hearts of fans, who are looking to these chaps to set the pace for the other members of the team,” the Times reported.

The following day found Corbett still in the fans’ favor: “Corbett and Hewitt, second and short, respectively, have broken into the local hall of fame by their fast work. Corbett is picked to be one of the fastest second basemen in the league, while Hewitt is covering a world of territory around short. These men look good on the infield, and if anybody beats Hewitt and Corbett out of their jobs they will have to play about the fastest infield seen around these parts for many days.”

First baseman Zach Wheat, starting his second season in professional baseball, likewise found favor with the Times: “Wheat can certainly dig the low throws out of the dirt, and hit the ball. He will be a star first sacker someday.” Wheat made it to the majors the following year, spent 19 seasons in the show, and wound up in the Hall of Fame.

The mercury rose to 78 degrees for Corbett’s first live-action test on Saturday, March 28, in an exhibition game against the St. Louis Browns. It was a forgettable performance, and Corbett learned the fickle nature of public opinion.

Facing pitcher Bill Grahame, a left-hander with a sharp-breaking curve who had compiled a 15-19 record in the Southern Association the previous year, Corbett went 0-for-4 and looked bad doing it. “Corbett is out of his class,” the Times concluded. “Corbett may be a good man, but he must ‘Missouri’ the Shreveport fans.” Four days ago, Corbett was a fan favorite. Now the fans said, show me.

Corbett redeemed himself the next day in another exhibition game against the Browns. He tallied two putouts, three assists, and no errors. Facing future Hall of Famer Rube Waddell, he scratched out a single, one of only three hits recorded by the Gassers.

“Corbett covered acres of ground around second,” the Times writer noted. “He seemed to have recovered from his stage fright of the preceding day, and showed his class.”

Meanwhile, Manager Gear was shedding players every day, trying to trim his team to the bare minimum before the first travel date, when a longer roster would cost the club in dollars paid to the Louisiana and Arkansas Railway.

Corbett hung on for another week – he was still in the Gassers lineup on April 5 – but the arrival of Cal Earthman, a highly-praised second baseman from Arizona, pushed Corbett from the roster. When Gear unveiled his projected starters in an April 11 exhibition game against Tom Fisher’s Sea Gulls, Earthman stood at second base.

Before the game, Gear told the Times that he had “a number of good men” available for sale or trade. Two days later, Corbett was 100 miles due east of Shreveport, playing shortstop and batting second for the Monroe Municipals of the Class D Cotton States League. Counting his four-game stint with Anderson in 1906, Corbett’s departure from Shreveport marked the second time a Class C team had canned him.

South Grand Street, Monroe, Louisiana, 1908.

South Grand Street, Monroe, Louisiana, 1908.

The Cotton States season had opened on April 2. The Municipals, managed by Jack Auslet, were 4-5 when Corbett joined the roster. Between Monday, April 13, and Saturday, April 18, Corbett appeared in five games with Monroe, playing shortstop and right field. He departed, his weak bat probably earning his release, with three hits in nineteen at-bats for a .158 average. During Corbett’s tenure, the Municipals won two games and lost three.

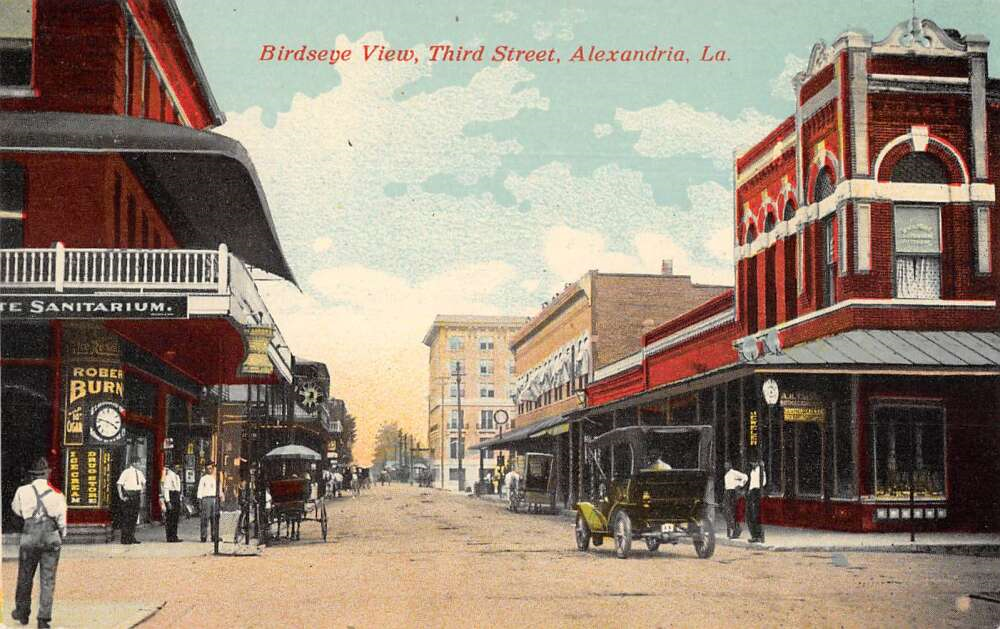

Third Street, Alexandria, Louisiana, early 1900s.

Third Street, Alexandria, Louisiana, early 1900s.

Fortunately for Corbett, Louisiana held more opportunities for a fast infielder with a strong arm and a CV that included Anson’s Colts and Friend of Tom Fisher. On April 24, he was 95 miles south of Monroe, in Alexandria, Louisiana’s Sportsman’s Park, playing shortstop for the Alexandria White Sox of the Class D Gulf Coast League in an exhibition game against his old Shreveport team. As he had in Shreveport, Corbett made a good first impression. The Alexandria Town Talk said, “Corbett, the Alexandria short stop, is a good one.”

Sportsman’s Park, Alexandria, Louisiana, 1908.

Sportsman’s Park, Alexandria, Louisiana, 1908.

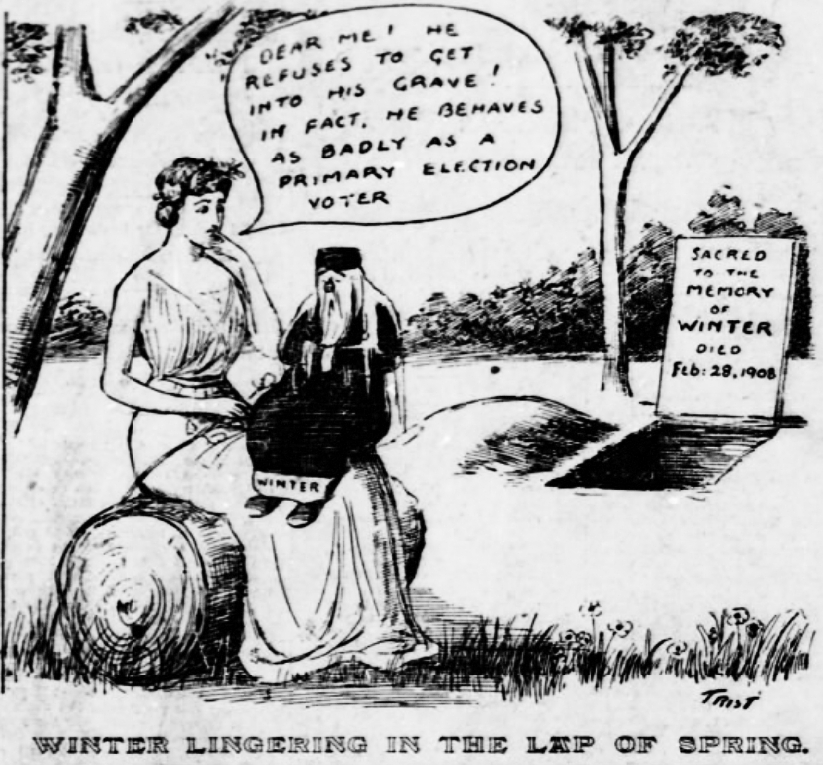

The White Sox opened their season on April 30 in Morgan City, Louisiana, a tiny town deep in the alligator-infested bayou country, just 15 miles up the Atchafalaya River from the Gulf of Mexico. A cold snap drove temperatures down to 65 degrees at game time, and a front-page cartoon in the New Orleans Times-Democrat depicted Winter Lingering in the Lap of Spring.

New Orleans Times-Democrat, May 1, 1908.

New Orleans Times-Democrat, May 1, 1908.

Despite the frigid conditions, the largest crowd ever assembled in Morgan City’s League Park watched the mayor stand on the mound and throw the first pitch to the president of the local ball club. Batting cleanup, Corbett went 2-for-4 and scored a run as the White Sox lost 3-4 in a 10-inning affair featuring 21 hits, an incredible 18 hit batters (if the box score is accurate), and six stolen bases.

The following day, Corbett moved up to the second spot in the order; he remained there, or batted leadoff, for the rest of his stay in Alexandria. The two-hole was his natural position by the logic that held sway in the pre-Sabre era. He could advance a runner with a bunt or sacrifice fly, was fast enough to leg out an infield hit or steal a base, had a little pop in his bat when he connected, and could hit for a reasonable average – against Class D pitchers, anyway.

Corbett seemed to settle in Alexandria, perhaps enjoying the unseasonably cool weather that held temperatures below 80 on some afternoons. He played every day, caught a few games – one of the few catchers fast enough to hit at the top of the order – and even pitched a complete game, giving up six runs and ten hits. The last statistics compiled by the Gulf Coast League gave Corbett a .263 batting average. The Alexandria Town Talk noted that Corbett was “playing good heady ball.”

Besides the White Sox, the Gulf Coast League included the Beaumont Cubs, the Crowley Rice Birds, the Lake Charles Creoles, the Morgan City Oyster Shuckers, and the Orange Hoo-Hoos. All of the clubs were failing financially. The Oyster Shuckers were the first to throw in the knife, followed by the Rice Birds, Hoo-Hoos, and Cubs.

The Alexandria White Sox played their last game of 1908 on Saturday afternoon, June 6, losing to the Lake Charles Creoles 0-1 in 10 innings. Their final record, 16-16, was good for third place in the Gulf Coast League. The circuit officially went belly up that evening.

The collapse of the Gulf Coast League sent seventy players to the unemployment line, giving managers in more solvent associations a chance to shore up their rosters. The Cotton States League, with clubs in Vicksburg, Jackson, Gulfport, Columbus, Meridian, and Monroe, was still a going concern but barely so.

The Monroe Municipals were nearly busted. An investigation by league president Arthur C. Crowder found “the men of the team unpaid, their board bills unpaid, the league dues unpaid, the visiting clubs unpaid and everything in a state of demoralization.”

The Meridian Ribboners were no better off. Late in the season, they found themselves stranded in Monroe, unable to afford train tickets to carry them to their next game. The team’s supporters were, in the understated words of the Vicksburg Evening Post, “very much downcast.”

And in Gulfport, the Sand Crabs could not attract the 200 quarter-bearing fans required to cover a visiting team’s $50 guarantee.

Corbett found a home with the struggling league’s Columbus Discoverers.

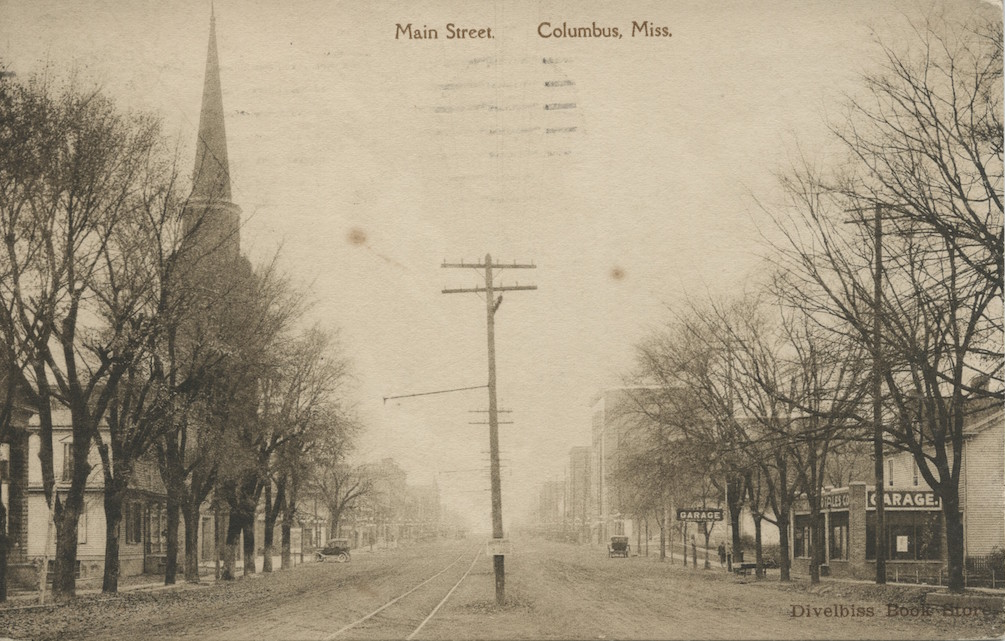

Main Street, Columbus, Mississippi, circa 1906.

Main Street, Columbus, Mississippi, circa 1906.

Columbus, Mississippi, was sited in Lowndes County on the edge of the Black Prairie Cotton Belt, a 300-mile-long crescent of rich dark soil weathering from the remnants of marine organisms that died 70 million years before the invention of baseball.

Following the Civil War battles at Shiloh and Corinth, Columbus became a hospital town as wounded men arrived by train and springless wagon. Nearly every home sheltered a sick or dying soldier. Over 2000 found rest in Friendship Cemetery.

The town was spared the war’s material destruction, and many large homes were still present in 1908. Today, they are known as Antebellum. Then, only 43 years after the fighting officially ended, they were just old houses. Lowndes County was William Faulkner country, where merchants, sawmill owners, and nascent industrialists were supplanting the planter class. The once-elegant mansions became barns and boarding houses.

The majority of Lowndes County’s residents were impoverished Black Americans. They loved baseball, but few had the time – or money – to come out to the ballpark and sit in the segregated bleachers. They worked “dark to dark,” hitting the fields before dawn and returning home after sunset.

Before the war, the town’s most prominent resident had been William Barksdale, mortally wounded on the second day of Gettysburg while leading the charge that carried his Mississippi Brigade through the Peach Orchard and onto the lower slopes of Cemetery Ridge.

When the 1908 season started, the most famous person in Columbus was former Confederate Lieutenant General Stephen Lee. He died on May 28 in Vicksburg after addressing a gathering of old Union soldiers. As Lee addressed the Federals, Corbett crouched at shortstop 172 miles southwest of Vicksburg in Crowley, Louisiana, where the White Sox lost to the Rice Birds.

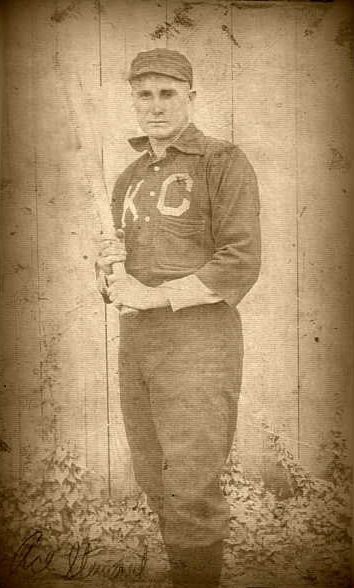

Asa “Ace” Stewart managed the Columbus Discoverers. The 39-year-old Indiana-born infielder had bounced in, out, and around professional baseball for 20 years. His credits included 97 games with the Chicago Colts in 1895, playing for Cap Anson.

Ace Stewart with the Kansas City Blues, 1900.

Ace Stewart with the Kansas City Blues, 1900.

Stewart suffered from the chronic nephritis that would kill him four years later. He was sick all winter before the 1908 season. He gamely showed up in Columbus for the Discoverers’ preseason workouts, but it was obvious that Stewart was not fit to manage. “He is in a very feeble condition,” the Evening Post reported, “and is not able to go on the field at all.”

His health continued to decline. The Jackson Daily News said, “Stewart’s health is wretched, and his many friends here say he will take a long rest and medical treatment for a stomach trouble.” He resigned and returned home to Terre Haute, Indiana.

Jack Toft, a 35-year-old catcher and first baseman, became the Discoverers’ new manager. Born in Pennsylvania, Toft had spent the last several seasons playing for the Class A Eastern League’s Toronto franchise, where he made his permanent home. He had never played in the Deep South and had a poor notion of the soul-crushing humidity that awaited him in Mississippi.

Toft lasted until May 20. Following a road trip to Monroe, where the Discoverers split a doubleheader on a muddy field in temperatures approaching 90 degrees, Toft resigned, citing the disagreeable climate. He hopped on a northbound train that afternoon, leaving the Discoverers momentarily managerless.

The Columbus directors once again called upon Ace Stewart. He had recovered sufficiently to stand in the third base coach’s box but had lost considerable weight and was said to be “not yet in proper condition.”

Stewart needed a second baseman. Dan Daley, his usual second-sacker, was batting 40 points below the Mendoza Line. Corbett had hit well in the Gulf Coast League, and Stewart summoned him to Columbus soon after Alexandria’s final game.

Once again, Corbett boarded a train bound for a new opportunity, a new chance to play baseball. He left Alexandria on Friday afternoon, June 12, as the temperature approached 90 degrees.

While Corbett sweltered in the unairconditioned train car, Ace Stewart hauled himself onto Jackson’s League Park diamond for a final appearance at second base. Against the Lawmakers, he was 0-for-3 with four putouts, two assists, a 1-6-4 double play, and no errors. Columbus lost 0-2. The next morning, Stewart resigned as manager of the Discoverers.

Stewart handed the Discoverers’ reins and their 28-28 record to Billy May, a 28-year-old pitcher. May was an Alabama boy playing his fourth season of professional ball. Unlike most minor league managers, he had not enjoyed the usual cup of coffee in the majors. The Evening Post described May as “an upright, intelligent, conscientious gentleman.”

Corbett’s exhausting 375-mile journey from Alexandria to Columbus allowed little time for rest between stops: Alexandria to Monroe on the Iron Mountain Railway; Monroe to Vicksburg on the VS&P; Vicksburg to Jackson on the A&V; and finally, Jackson to Columbus on the Illinois Central.

He first appeared in a Columbus uniform on Monday, June 15, facing the Monroe Municipals in Columbus’s Lake Park.

When Corbett trotted out to face his old team, he still showed the effects of the trip from Alexandria. The sports editor of the Columbus Weekly Dispatch, somewhat confused about the new man’s origin story, said, “Corbett, the second baseman recently secured from Lake Charles, made his initial appearance Monday afternoon, and did not show up well. It is possible, however, that he was tired as a result of travel, and may improve.”

The Discovers won 5-1, with Corbett making no hits but walking twice and recording a sacrifice. Playing second base, he made two putouts, one assist, and one error.

The Weekly Dispatch writer was more approving of Corbett’s play two days later: “Corbett, the new second baseman, showed up better Wednesday afternoon, having accepted seven chances without an error.”

He finished the week with some nice stickwork. In the second game of a Saturday doubleheader against the Gulfport Sand Crabs, with the Discoverers trailing 3-4 in the ninth inning, Corbett drove in the tying run to send the game to extra innings, then doubled in the eleventh to drive home the winning run. The Dispatch labeled his hitting “the feature of the game.”

Corbett’s early performances in Mississippi received mixed reviews. After his first ten games, in which the Discoverers went 6-3-1 (a tied game ended in darkness), an item in the Vicksburg Evening Post – which, based on the wording, was probably a “special” from the Columbus sportswriter – read, “Corbett, who recently succeeded Daley at second, is showing up fairly well. His playing, however, is erratic, being at times brilliant and at times bum. He seems conscientious and perfectly willing to work, but on several occasions both brawn and brain seemed to become suddenly numb, and he has been guilty of inexcusable errors that were exceedingly costly.”

After another week of games, the Columbus Dispatch scribe was still unconvinced of Corbett’s worth: “Corbett is now at the second station, but is too erratic to be depended upon. His playing, while at times brilliant is at other times just the reverse, and at this stage of the game there should be a man at second who could always be depended upon to deliver the goods.”

In a July 1 game against the Vicksburg Hill Billies he was on first with two outs when the batter lofted a soft fly to the pitcher, who muffed it. Meanwhile, “the sleepy Corbett,” as the Evening Post described him, was still standing on first and was easily forced at second, the infield fly rule not applying with two outs. The Post’s writer uncharitably called the sequence “a nut play.”

Corbett came to Columbus with the reputation of a dependable but unspectacular hitter, and Manager May inserted him into the order’s five spot. Corbett hit well; after two weeks of games, his average approached .280. May promoted him to leadoff. His average immediately nosedived. After ten games at leadoff, Corbett pierced the Mendoza Line.

Before the advent of the modern farm system, minor league clubs were independent entities. Each team had to gather and pay its own players. Player-managers scouted and signed players, sold the contracts of players coveted by other clubs, and released the castoffs. Many player-managers acted as the club’s secretary, handling all of the correspondence and paperwork.

Columbus manager Billy May was found lacking on the managing and administrative side. “Billy is a great pitcher and an all-round good fellow,” the Evening Post said, “but when it comes to executive ability, he fans out.”

The Discoverers relieved May of his management duties on July 8. Lou Hall, a pitcher and utility man whose reputation exceeded his accomplishments, inherited the Discoverers’ 37-40 record and their fourth-place standing in the Cotton States League.

Hall had played for ten teams in the previous five seasons, mostly in Class D, and had no major league experience. He had opened the 1908 season as an umpire.

When Hall visited Jackson, the Daily News offered a somewhat sarcastic rendition of his arrival: “O, mamma, guess who’s here? Likewise, mother, observe whom has arrived. Lou Hall, big, brawny old Lou, with his baby-blue eyes, his brain-storm ways, and his seraphic smile, floated into Jackson this morning.”

Rosters in the Cotton States League comprised 12 men with a total monthly payroll, excluding the player-manager’s salary, of $1000. Each player made about $90 each month.

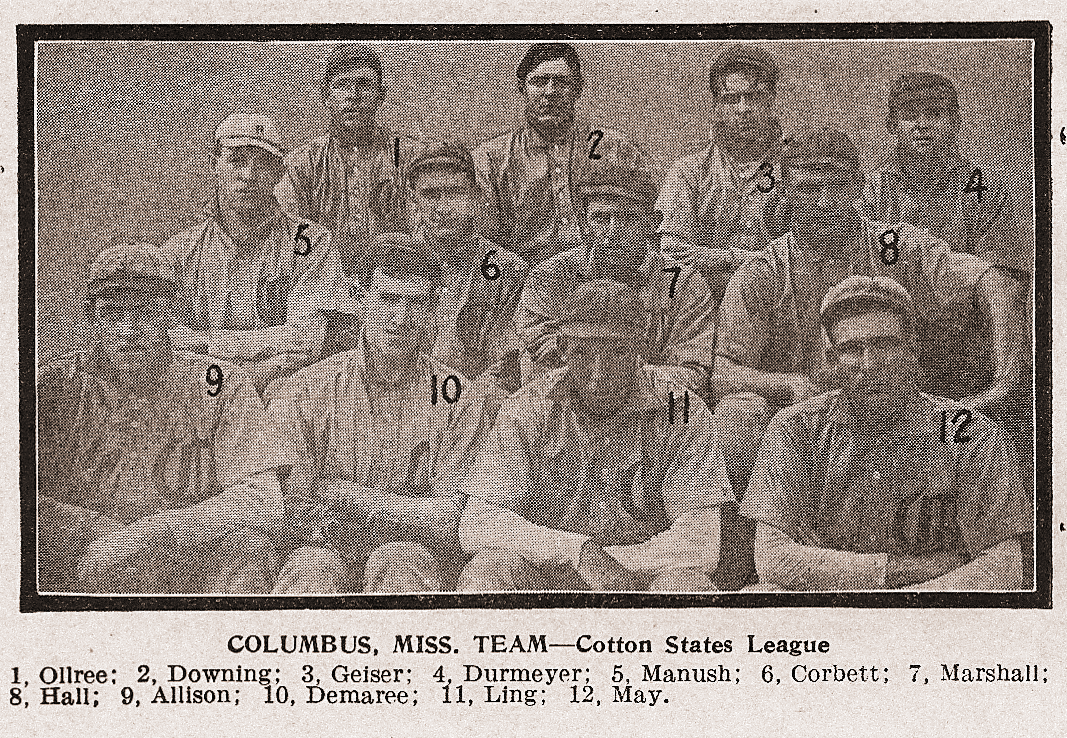

After Hall’s arrival, the Discoverers’ roster comprised Bill Ling (1B), Corbett (2B), Charlie Durmeyer (SS), Frank Manush (3B), Roxie Ollree (LF), Jake Geiser (CF), Ray Marshall (RF), Pat Downing (C), and pitchers Al Demaree, Mack Allison, and Billy May. Hall acted as a utility man, playing first and second base, right field, and occasionally taking the mound. All of the pitchers recorded games in right field.

The regular position players took the field every day unless they were injured. Durmeyer, Manush, and Marshall played in all 119 of the Discoverers’ games. Downing, a 25-year-old Kentuckian in his final year of professional ball, crouched behind the plate through 104 games in the misery of the Mississippi summer. Corbett played every inning of every game from the day he joined the Discoverers until the end of the season.

Columbus Discoverers, 1908. Corbett is in the middle row, second from left (6).

Columbus Discoverers, 1908. Corbett is in the middle row, second from left (6).

With Corbett batting near .200, Hall sent him to the bottom of the order. He first stuck Corbett in the seven slot. His average continued to fall. When the number neared .170, Hall dropped him down to eighth. If the strong-hitting Billy May took the mound, Corbett might suffer the dishonor of a position player batting ninth.

But Hall must have seen something in Corbett. Though Corbett could barely hit his weight, Hall put him on the field every day. In mid-July, with temperatures in the upper 90s over most of Mississippi and Louisiana, when a person broke into a sweat sitting idly beneath an oak tree and mosquitos penetrated every aspect of life, the kid from Indiana settled in.

The Vicksburg Herald’s sportswriter said Corbett’s fielding was “gilt-edged.” The Columbus Commercial labeled Corbett “our crack second baseman.” Even the difficult-to-please writer at the Dispatch conceded that Corbett was “doing well.” His average average leveled off and inched back above .200.

The final weeks of July brought rain to the South. Rain fell every day in Louisiana and Mississippi. Some areas received continual rain for over a week. The rain wreaked havoc on the Cotton States League’s schedule, forcing the cancellation of many games.

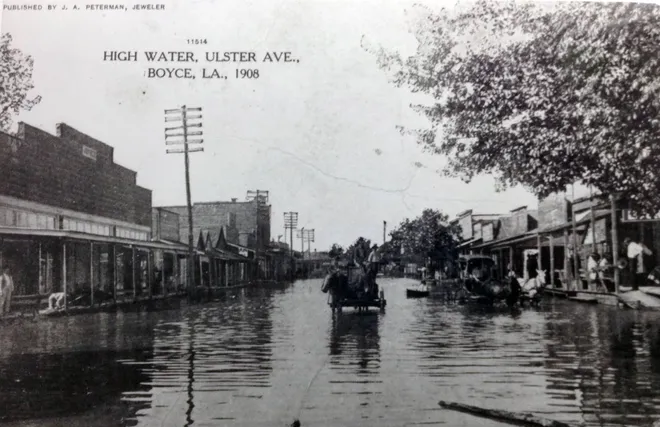

Ulster Avenue, Boyce, Louisiana, 1908.

Ulster Avenue, Boyce, Louisiana, 1908.

In Vicksburg, the second-place Hill Climbers and the first-place Jackson Lawmakers attempted to play an August 1 game after 48 hours of rain. The Vicksburg American said, “The diamond was several inches deep with mud and water.” The Evening Post was more constrained, describing the diamond as only “ankle deep in mud.”

Before 1950, the home team had the option of batting in the top or bottom of the inning. Vicksburg manager George Blackburn chose to bat first, hoping the Jackson infielders might compress the mud of the diamond. “It did no good, however,” the American said.

The American’s man described a game never seen in the modern era: “After the game started the rain poured and at times it was so dark the ball could hardly be seen, but Umpire [Wilson] Matthews insisted that the game be played out the full nine innings, notwithstanding all the players were thoroughly soaked… Blackburn was kept busy supplying dry balls with which the game could be played.”

The Post reported that Vicksburg pitcher Clay Robb, a baseball comedian known as The Clown, helped his cause by doctoring the ball: “Robb’s ingenuity helped him to control the ball for he laid in a supply of talcum powder and used it copiously, while his opponent had to grasp the slick horsehide.”

As Umpire Wilson Matthews desired, nine innings went on the books, with Vicksburg winning 6-2. “At the close of the game the field was a sea of mud and water, ” the Post noted.

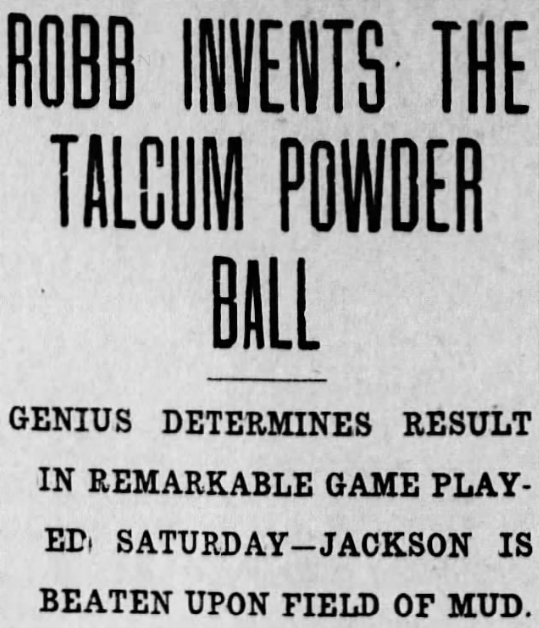

Vicksburg Evening Post, August 3, 1908.

Vicksburg Evening Post, August 3, 1908.

The following day, Corbett and the fourth-place Discoverers played the third-place Gulfport Sand Crabs in New Orleans’ Pelican Park. The game showcased the Cotton States’ product to the more sophisticated fans of the Crescent City, whose Pelicans were leading the Class A Southern Association. But the bushers failed to impress the few fans who turned out.

A writer for the New Orleans Time-Democrat provided a harsh assessment: “There have been some choice exhibitions of bone-headedness in this neck o’ the woods by Southern League players, but it remained for the visitors to demonstrate that one has to import talent to see chuckle-headedness in its Simon purity.”

“In the first place the grounds were in a miserable condition,” the writer continued. “The space around the plate was soggy and the pitcher’s box was a mass of mud. The ball had no life to it after it had been in play a few times, and had to be retired repeatedly to put it in shape.”

The eighth inning opened with the home team Discoverers leading 3-1. But Allison, the Columbus pitcher, was tiring. A walk and three hits reduced his lead to 3-2 and loaded the bases.

The next Sand Crab drove the ball into the mud in front of home plate. As catcher Pat Downing worked to pry the ball from the ooze, the runner on third raced home to tie the game.

Freeing the ball, Downing pegged it to first base, manned by manager Lou Hall, to force the batter. The Sand Crab on first had, for some reason, not advanced fully to second, and with the batter retired, he retreated to first. Hall stepped on the bag but failed to tag the runner.

When the ump ruled the runner safe, Hall set up a great howl, maintaining – by logic that has been lost to history – that a tag was unnecessary. While Hall remonstrated, the Sand Crab on second base continued around the bases and scored to give Gulfport a 4-3 lead.

Hall continued to protest. After what the Times-Democrat reporter labeled “a long interval of rowing and disputing, which completely disgusted the small crowd of fans,” the umpire gave up and declared the game a forfeit in favor of the Sand Crabs.

In the closing days of the Cotton States’ season, Downing suffered an injured finger. Hall went to second base and sent the flexible Corbett behind the plate. On August 15, he caught a no hitter by future big leaguer Al Demaree. Corbett allowed a single passed ball while Demaree struck out nine and walked four.

Corbett played the next two games in right field. He acquitted himself well in an August 17 win over the Jackson Lawmakers. “Marshall and Corbett were the stars,” the Daily News reported. “Marshall got three hits out of four times and Corbett in right field accepted six chances without an error.”

The Discoverers closed out their season on August 19 with a doubleheader against the Jackson Lawmakers. Corbett again donned the Tools of Ignorance.

Sammy LaRocque, a 45-year-old Canadian known around the league as “Dad,” umpired the games. Larocque had just completed a 23-season career stretching from 1884 through 1907 that included 124 games in the majors.

The players respected LaRocque. The Weekly Dispatch said, “He always has a smile on his face, and while firm is never despotic or overbearing. The players obey his command because they realize the fact that he not only knows the game, but always gives every man a fair deal.”

During the first game of the Discoverers’ twin bill, with the temperature over 95 and the score tied 3-3, LaRocque called Durmeyer out on a close play at second. One of the Discoverers loudly remarked that LaRocque had handed the game to the Lawmakers.

It was all the encouragement LaRocque needed to escape from Mississippi’s heat, humidity, and mosquitos and return to Canada where he belonged. He left the field, walked to the dressing room, changed out of his cleats, and was outside the ballpark waiting for a streetcar when the offending player chased him down and apologized. LaRocque returned to his place behind the plate, and the game continued.

With one out in the bottom of the tenth, the Jackson pitcher issued a single and three straight walks, one to Corbett, to force in the winning run. With little regard to the historical knowledge of future readers, the Daily News said, “Corbett violated the Hepburn Act,” a reference to a 1906 law that eliminated the railways’ practice of providing free rail passes to high-volume shippers.

The second game of the doubleheader ended after five innings with Jackson leading 3-0. The Discoverers’ 58-56 record left them in fourth place.

The 1908 season was a qualified success for Jack Corbett. Between late March and late August, in the strange new world of the American South, Corbett played on four different teams in three different leagues. He bombed out at Shreveport before the season started, lasted just five games in Monroe, established himself in Alexandria before the entire league cratered beneath him, and found a home in Columbus. For his five months of work, Corbett probably earned about $450, equal to what the average American farm hand made in a year.

Corbett’s fielding averages in the Cotton States League, including his work Monroe, were .953 at second base (56 games), .900 in the outfield (7 games), .950 at catcher (3 games), and .883 at shortstop (3 games). His final Cotton States batting average was .215.

Corbett proved he could hang with Class D competition, though his grip was tenuous at best. His fielding was stellar, but his hitting was barely adequate, even on the lowest rung of the professional baseball ladder. He was flummoxed if he stepped up to Class C, where the curves broke slightly sharper, or the pitchers could sometimes hit the corner for a strike. His speed, smarts, and fielding ability kept Corbett in professional baseball, but his weak hitting confined him to the now-forgotten ballparks of failing Class D clubs.

Many men gave up when they realized they could never rise to a higher class. But Jack Corbett stayed with it, stayed in the lower minors for another nine seasons. Shreveport, Monroe, Alexandria, and Columbus were the first steps on a pilgrimage that carried Corbett to Charleston, another Anderson, Spartanburg, Mobile, Asheville, and finally to Columbia.

Young men like Corbett were drifters who plied their trade – playing baseball – in hot little towns, chasing hints of a job through Western Union offices, train stations, and dirt roads to whatever decaying ballpark might yield a vacancy in the lineup. Players like the 1908 version of Jack Corbett made the roster because they were just a little bit better than the man released the day before.

After the Discoverers’ final game, the Columbus Commercial remarked upon the players’ departures: “Corbett went to Chicago, Downing returned to his home in Paducah, Ky., and the rest of the players went to various places to hustle for jobs which will keep them provided with cigarette money until the return of spring.”