Mance Lipscomb – Farmer and Songster

I worked so hard in my lifetime, look like I dreams about it now. And I wake up in the morning, thinking I got to go to the field.

— Mance Lipscomb, I Say Me for a Parable

I. The Cotton

I. The Cotton

The southern extremity of Brazos County, Texas is covered by a broad expanse of Quaternary alluvium deposited by floods of the Brazos and Navasota rivers stretching back for thousands of years. The soil is predominantly Miller Clay, described in a 1916 soil survey as “sticky and tenacious when wet, and rather difficult to cultivate… It assumes a crumbly structure upon drying, and is commonly referred to as buckshot land.”

Big Creek, an abandoned channel of the Brazos, snakes across the plain. Here, overbank deposits have created natural levees of Yohala Loam, lighter in color than the Miller Clay and a few feet higher in elevation. The tiny settlements, widely-spaced clusters of habitations, are sited on these terraces. The Miller and the Yohala are excellent producers of cotton.

Standing on the tracks of the Santa Fe railroad that bisect the land, a modern visitor perceives a perfectly flat ocean of red dirt bordered in the far distance by a low ridge bearing a fuzz of scrubby trees and a few buildings. The soil survey, written by a government agriculturalist, tells us that “the Brazos and Navasota rivers are bordered by wide alluvial bottoms, which unite at the southern end of the county, so that the county consists simply of a central upland division, with belts of low-lying bottom land on the east, west, and south.”

In his oral autobiography, I Say Me for a Parable, Mance Lipscomb described the land more succinctly: “Tween the Brazos and the Navasot’, it ain’t nothin’ but bottoms.”

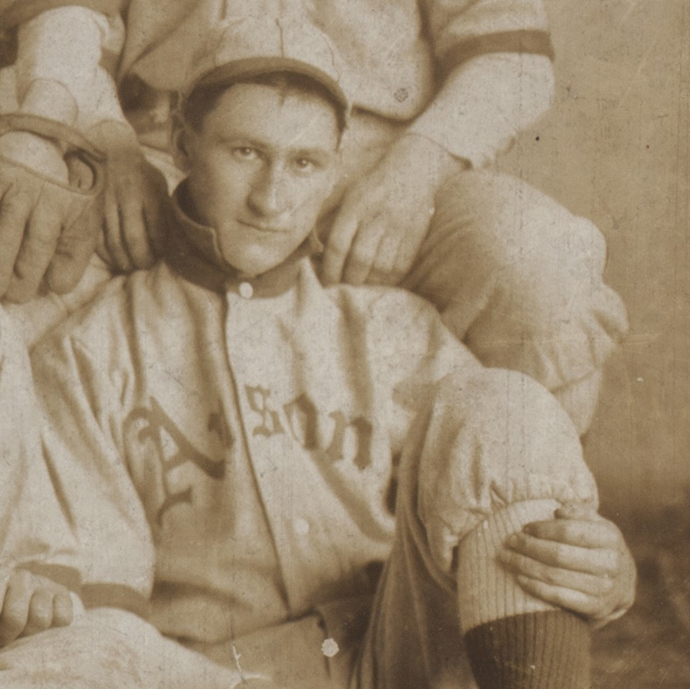

Mance Lipscomb was born in 1895 on the eastern edge of this red clay moonscape, probably on the two labors of land (one labor, pronounced LAH-bor, is about 177 acres) purchased by H. Mickleborough in 1859. Mance’s presence pre-dated the boll weevil, which emigrated into the area five years later. His given name was Bodyglin, the spelling of which flummoxed the taker of the 1900 census who recorded it as Boly G. A year after his birth the entire area flooded; everything between the Brazos and the Navasota was under water creating a single river twelve miles wide. The tracks of the Santa Fe railroad were six inches below the surface. While still a young man Bodyglin began calling himself Mance, a name borrowed from a friend of his older brother.

The social order into which Mance arrived had been established in the 1820’s when Stephen F. Austin sold 307 tracts to a select group of colonists known as the “Old Three Hundred.” Most of the prime cotton land in what became southern Brazos County was purchased by the Millican family. Robert Hemphill Millican received 2½ sitios (one sitio = 4338 acres, roughly equivalent to a league). His sons — Elliot, William, and James — were each granted one sitio. The Millican family owned a few slaves; Jared Groce, their neighbor across the Navasota River in Grimes County, owned ninety. The entire lot had to clear out during the Runaway Scrape of 1836, and Robert Millican died of measles and pneumonia near the Trinity River, more than one hundred miles from his home.

The social order into which Mance arrived had been established in the 1820’s when Stephen F. Austin sold 307 tracts to a select group of colonists known as the “Old Three Hundred.” Most of the prime cotton land in what became southern Brazos County was purchased by the Millican family. Robert Hemphill Millican received 2½ sitios (one sitio = 4338 acres, roughly equivalent to a league). His sons — Elliot, William, and James — were each granted one sitio. The Millican family owned a few slaves; Jared Groce, their neighbor across the Navasota River in Grimes County, owned ninety. The entire lot had to clear out during the Runaway Scrape of 1836, and Robert Millican died of measles and pneumonia near the Trinity River, more than one hundred miles from his home.

When the Civil War arrived, a large swath of the original Millican grants — now known as Allenfarm — was owned by John D. Rogers, an Alabama-born physician with a net worth of $45,000, equal to $1.4 million today. Rogers raised a company of volunteers — the Dixie Blues, later Company E of the 5th Texas Infantry Regiment — and entered the Confederate army as a captain. The “Bloody 5th” was a legendary unit, attached to the Army of Northern Virginia and engaged in nearly every battle fought in the eastern theater. Dr. Rogers missed most of the fighting, though. In 1862 he resigned his commission in order to return home and recover from pneumaturia — bubbles in the urine — a condition that, in the words of the regimental surgeon, “thoroughly disqualified him for the performance of his duties as an officer and soldier.”

By 1870 both the doctor and his plantation had recovered. The Galveston Daily News reported that a stalk of Dickson cotton grown on Allenfarm contained over 300 large bolls “and it was evident that many had dropped off on the way.” It was estimated that the crop would yield three bales per acre (about 1500 pounds), a very good yield by today’s standards.

Like Dr. Rogers, Mance’s father, Charles, was born in Alabama and emigrated to the bottom lands of the Brazos. But Charles’s path was slightly different. He was born into slavery, was brought to Texas with his family when he was still a boy, and was sold to someone named Lipscomb. After the war, freedom brought poverty even worse than before. “When slavery ended up, my daddy was eight years old,” Mance related in his autobiography. “He didn’t know nothin’ ‘bout a pair of pants, and didn’t know nothin’ ‘bout a hat. He wore a shirttail, old low shirttail ‘til he was fourteen years old… And he didn’t know nothin’ ‘bout but three letters in food: Meat, Meal, and Molasses. Three Ms! No flour, no sugar, no coffee.” The 1900 census notes that Charles could read and write, but that his wife, Jane, could not.

People like Charles Lipscomb were now farming the same crop of cotton that they had farmed before the war, and for the same landowners.

The cotton crop began with the planting, which usually took place between March 10 and April 15. Timing was everything. Plant too early and the seeds could be damaged by one of the late freezes that the Texas spring hides up its sleeve. Plant too late and the open-but-unpicked bolls might be saturated and ruined by the early autumn rains. In the days before satellites and sophisticated weather models, choosing the day to commence planting required communion with the full range of spirits at one’s disposal.

The cotton crop began with the planting, which usually took place between March 10 and April 15. Timing was everything. Plant too early and the seeds could be damaged by one of the late freezes that the Texas spring hides up its sleeve. Plant too late and the open-but-unpicked bolls might be saturated and ruined by the early autumn rains. In the days before satellites and sophisticated weather models, choosing the day to commence planting required communion with the full range of spirits at one’s disposal.

Mance said that Jane Lipscomb was known for her ability to pick the planting day. “My mother was a séance on when to plant. Never missed it in her life. People come to be schooled by her, on the farms where she working on. She was known [to be] aware. See, she had sense enough to not plant, and sense when to do it.”

Mance joined his mother in the fields when he was ten years old, picking fifty pounds of cotton each day under the sun of a Texas August, when temperatures are usually approaching 100° F. No shade among the plants; maybe a few scrubby trees along the turnrow. The following year, Mance was picking 100 pounds each day. That was the year he started plowing, though the eleven-year-old could barely reach the plow handles. By the time he was eighteen, Mance could pick 300 to 350 pounds each day. And one day when he was sixteen, Mance picked 500 pounds of cotton. “That liked to killed me,” Mance said later.

Imagine the weight of a puff of cotton. Imagine how many of those puffs you would need to make one pound. And multiply that by 300. Each puff — surrounded by spines and burrs that can slice open your finger — must be pulled from the plant individually, and stuffed into a ten-foot-long towsack that the picker drags down the row. Then imagine doing that every day for a month, two months, three months, sometimes moving over the same field three times to ensure that every boll has been picked.

Between the planting and the picking, the crop was thinned and weeded, a chore known as chopping. It must have been brutal, back-breaking work. I grew up hearing people engaged in manual labor, no matter how difficult the task, say I’d rather do this than chop cotton. One day when a young Mance was wielding his hoe without conviction, Charles Lipscomb gave his son a Life Lesson: “Whatever you do, don’t care what it is, you give it the best lick you got. Then you don’t have to be hung down and sorry for what you done. You’ll have a good feeling towards what you done, and towards yourself. Now you go on and take that hoe, and chop it like it ought to be chopped.”

Between the planting and the picking, the crop was thinned and weeded, a chore known as chopping. It must have been brutal, back-breaking work. I grew up hearing people engaged in manual labor, no matter how difficult the task, say I’d rather do this than chop cotton. One day when a young Mance was wielding his hoe without conviction, Charles Lipscomb gave his son a Life Lesson: “Whatever you do, don’t care what it is, you give it the best lick you got. Then you don’t have to be hung down and sorry for what you done. You’ll have a good feeling towards what you done, and towards yourself. Now you go on and take that hoe, and chop it like it ought to be chopped.”

II. The Music

As Mance was becoming a farmer, he was also becoming a musician. Jane Lipscomb bought her son’s first guitar when he was around twelve years old, on credit, for $1.50. That was a lot of money when the family was barely surviving on fifty cents a day. The guitar had only three strings and the wood was so thin that the sunlight could pass through it. Charles Lipscomb was a fiddler, and Mance’s older brothers were good guitar players. Mance took to the instrument, played it every spare moment, and by the time he was fourteen he had passed his brothers “like a pay car passin’ a tramp.” One of the first songs that he learned to play was “Sugar Babe.”

In a late-60’s film recorded at the University of Washington by the Seattle Folklore Society, Mance — playing with a broken ring finger on his right hand — opens with “Sugar Babe,” and follows it with “Ella Speed,” a song about a murder in Dallas that became popular around 1912. In “I Want to Do Something for You” a man offers his crush a string of gifts — a strip of land, a house and home, a diamond ring, and a Chevrolet — before finding what she really wants: a Sedan Ford. “Baby Please Don’t Go” is introduced as “one put out in ’42; come out from over in Louisiana.” The set closes with “Shine on Harvest Moon,” of which Mance says, “I think somebody here might rememorize that song.”

The songs in the film — just five of the over 300 in Mance’s repertoire — aren’t classic blues. These are songs for people who want to dance, and contain elements of ragtime, country, and even pop. It’s a short step from these songs to the Rolling Stones. Mance’s trademark style featured a strong, percussive bass droning behind treble figures that often edged into rockabilly. In 1969 Mance told a reporter from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, “Most of the young singers have to have a band behind them, but I don’t need no band ’cause I can play my own bass. If you listen when I play, you can hear two guitars — my thumb plays the bass part and these two fingers [index and middle fingers] do the rest.”

Mance never considered himself to be a bluesman because he played more than blues. He called himself a songster, someone who compiled a mental library of songs in many styles, and who shared those songs with the people that he met. The main venues for the sharing of Mance’s songs were the Saturday night suppers that were a social staple in the Brazos bottoms. Mance was the most sought-after player in the bottoms because he played music that people could dance to. Mance referred to himself as “the big Ace of this country… If somebody couldn’t get me, they didn’t have no to-do goin’ on.” The going rate for Mance’s presence at a dance was $1.50. He made a few dollars more if he could pass a hat.

Describing the suppers, Mance said, “Everybody there, little and low, big and wide, has got ’em a half bottle of beer in their hand.” There were no amps or PA systems at the dances; the performer’s volume was a matter of how loud he could sing and how hard he could hit his guitar. Broken strings were common. Sometimes the dances didn’t end until mid-morning Sunday. Being able to play in a variety of keys kept Mance’s fingers from cramping up.

A small army of gamblers besieged every Saturday night supper. Always shooed away from the food inside, they had to play outside, laying out their cards in the dirt and grass. Mance would stand at a window and play “Jack of Diamonds” for the card players, hoping that his inspiration would be repaid with a bit of cash in the hat.

Introducing “Jack of Diamonds” in the Seattle Folklore Society film, Mance refers to the number as a “knife piece,” a song played in an open tuning using a pocketknife for a slide. I had always assumed that the old blues players who used a pocketknife somehow held it parallel to their fingers, the way pedal steel players hold their bar. Watching the film, I was surprised to see that Mance grasped his knife by one end, flicking the back of the casing across the strings. The video also provides a good view of Mance’s thumb work on the bass strings.

III. The Years

In the first week of December, 1913 the Brazos bottoms flooded again, a disaster that made news all over the country. The Knoxville News Sentinal reported that at least fifty people had perished and that the flood forced hundreds of farmers and their families to seek refuge in the treetops, clinging to the branches in the miserable December weather for over forty-eight hours. The Arizona Republic tells us that twelve Black farmers lost their lives on the John Parker “plantation” near Allenfarm. And the Fort Worth Star-Telegram warned that anyone in the Brazos bottoms who survived “will be practically destitute.” A week later, Mance married Elnora Kemps. They were together for the next sixty-two years.

Mance registered for the draft in 1917 when he was twenty-two — the form records his age as twenty-one — and employed by Dr. Stonewall Jackson Emory at the same farm on which Mance had been born. The form tells us that he was of medium height and weight, and not bald. Originally classified as 1 (eligible and liable for military service), Mance later received an exemption: he was supporting a wife, a child, a sister, a brother, and his mother. The following year an airplane flew over a field in which Mance and thirty-five or forty other men were working. Fifty mules stampeded, some dragging men by the traces. Two years later the 1920 census noted than Mons Lipscomb was a Farmer working on his own account.

That account was perpetually in the red. Mance was working caint to caint five days a week — he starts when he can’t see because the sun isn’t up, and stops when he can’t see because the sun is long down — plus another half-day on Saturday. “But every year I’d get in debt a little deeper,” he explained in I Say Me for a Parable. “I was born a slave and didn’t know it. My daddy was eight years old when slavery time [was] declared freedom. The white people never did change it. I call myself a slave until I got somewhere along about forty-five years of age. I had to go by the landowner’s word. Do what he said to get a home to stay in. And then when I make my crop, why he sold the cotton and figured it out his own way and brought me out in debt.”

The Brazos River froze bank-to-bank in January of 1930 when the temperature sank below 0°F. It was an event that Mance associated with the arrival of Yank Thornton. “Let’s see, he come in there, I believe, in ’29,” Mance remembered forty-fours years later. “Little before that first big freeze come here and made ice over the Brazos.”

Thornton was working on a farm owned by the Moore Brothers. One of the brothers, Tom Moore, had a reputation in the bottoms that was… mixed. He was either a Great Man or the Devil Himself depending on who you asked. It’s a description that fits every prototypical Texas oilman and rancher. Think Jett Rink. If you asked the farmers who worked the Moores’ land, the needle would stray to the Devil side of the dial. Yank Thornton sang some words about Tom Moore, which Mance set to music. “Tom Moore’s Farm” (also known as “Tom Moore’s Blues”) became one of Mance’s most well-known songs and was among the first that he recorded.

When “Tom Moore’s Farm” was released in 1960 on 77 Records’ A Treasury Of Field Recordings Vol. 2: Regional and Personalized Song (the extensive liner notes by Mack McCormick are worth a read), the track was credited to Anonymous; Mance didn’t want his name on it if word got back to Tom Moore. “There’s so many things I could say about him,” Mance said thirteen years later when dictating I Say Me for a Parable. “If it get back to him he liable to shoot me down yet.” And when asked to play the song, Mance replied, “You want me to go home with my eyes shut?”

Ain’t but the one thing,

See what I done wrong

Ain’t but the one thing,

See what I done wrong

Moved my family

Down on Tom Moore’s farm

Go to work in the mornin’,

Stops at one o’clock

Go to work in the mornin’,

Stops at one o’clock

Hold back dinner time

But you sure can’t hold back dark

Standin’ on the levee

With his spurs in his horse’s flanks

Standin’ on the levee

With his spurs in his horse’s flanks

Whuppin’ his hat

Watchin’ boys from bank to bank

Mance registered for the draft again in 1942. The registrar noted that the 47-year-old man was dark brown, 5 foot 10 inches tall, weighed 156 pounds, and had three scars on his right arm.

In the 1940s the Moore Brothers purchased Allenfarm, the old Millican grants that were later owned by Captain John Rogers. The Moore family still owns most of it. From ’45 to ’56 Mance played the Saturday night dances at Allenfarm, taking in three-and-a half dollars each night.

In the 1940s the Moore Brothers purchased Allenfarm, the old Millican grants that were later owned by Captain John Rogers. The Moore family still owns most of it. From ’45 to ’56 Mance played the Saturday night dances at Allenfarm, taking in three-and-a half dollars each night.

Around 1945 Mance was finally able to edge his farming account into the black — barely — after a kind landowner extended what now might seem like an insignificant favor: he gave Mance four mules and a cultivator.

Farmers without their own team or implements had to go halvers: the landowner provided the mules and the tools in exchange for half of whatever the farmer produced. The landowner also provided both humans and animals with shelter, food, and care, with the cost being charged to the farmer’s account. It was nearly impossible for the farmer to come out ahead under this arrangement. But a farmer with his own team and implements could rent some land on thirds and fourths: “Havin’ my own team, that brought me up to thirds and fourths: every third load of corn, and every fourth bale of cotton, well that was the landowner’s.” It was a marginally better deal, and Mance was finally able to clear a small amount at year end: maybe $200 if he was lucky.

In 1956 Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, the Soviet Union invaded Hungary to crush a nascent revolution, and the government of Cuban president Fulgencio Batista suspended constitutional guarantees after rebels attacked an army garrison. In Mance Lipscomb’s country, a missile being tested by the Navy fizzled out at 10,000 feet and crashed back to the earth; General Curtis Lemay, chief of the Strategic Air Command, warned that the Soviet Union was outstripping the United States in the production of intercontinental bombers; Dwight D. Eisenhower defeated Adlai E. Stevenson in the presidential election; and Elvis Presley had a big hit with “Heartbreak Hotel.”

Nineteen fifty-six was also the year that Mance finally gave up trying to scrape a living from the Brazos bottomlands while laboring within a ninety-year-old socio-economic system that was designed to keep him impoverished. When a landowner claimed that Mance owed him $500, Mance recalled the advice of his father: “If you can’t pay a man in full, you pay him in distance.” He decided to put some distance between himself and the bottomlands by moving to Houston. He and Elnora had fourteen dollars, a trailer-load of household goods, and fifteen freshly-killed hens destined for a deep-freeze.

And here our story crosses a dip in the road, and we experience a brief sinking sensation before the tires gain traction and we climb into the sunlight. In Houston, Mance was badly injured while working for a lumber company. He received a $3500 settlement, half of which went to his lawyer. With the remainder, Mance was able to have a house built on a three-acre lot in Navasota, a town just across the Navasota River from the bottomlands, in Grimes County. He owned the property free and clear. No halvers, no thirds and fourths. Mance was sixty-five years old.

“You just try to live right. One of these days a little right come comin’ to ya.”

IV. The News

IV. The News

Navasota was where the more well-off residents of the area lived. Mance had played for dances in Navasota, on Friday and Sunday nights, parties that ended no later than 1AM. Tom Moore had his office in Navasota, over a bank. When Mance built his house there Navasota numbered about 5000 souls. Glen Alyn, the compiler and editor of I Say Me for a Parable, arrived in Navasota in 1973 and saw a town that “resembled Vicksburg more than Fort Worth.”

Chris Strachwitz and Mack McCormick drove into Navasota in the summer of 1960, hoping to find folk or blues musicians — with luck another Lightnin’ Hopkins — to record for Strachwitz’s new Arhoolie Records. It was Tom Moore, co-owner of Allenfarm, who directed them to Mance Lipscomb. The two were familiar with Moore, by reputation at least, through Hopkins’ version of “Tom Moore’s Farm” (titled “Tim Moore’s Farm,” an attempt to disguise the subject of the song). According to Strachwitz, he and McCormick called on Mister Moore and asked if he “happened to know of anybody who plays music for your field hands when they have a party or when they have suppers.” Moore replied, “There’s this fella here in town, people here seem to like him, and he plays music.” Tom Moore didn’t know the player’s name, but Pegleg down at the train depot led them to Mance.

John Bryan, then a resident of Houston, was one of the first to learn of Strachwitz’s and McCormick’s find. Writing a year later for the San Francisco Examiner, Bryan said, “I vividly recall one hot day last summer when the head of the local folk music club and noted blues collector, Mack McCormick, came speeding back from Lipscomb’s little shack with news that he had just discovered a true Negro ‘folk singer.’ Not just a guitarist with an ear for catchy ‘pop’ blues, but a weathered, seasoned veteran of years of anonymous folk music, a great-grandfather, son of a slave, who played in a variety of forms popular half a century ago, such forms as drags, jubilees, reels, shouts, breakdowns, the traditional music of his people.”

It can be cringe-inducing to read — and quote — Bryan’s words over half-a-century after they were written. But the article is typical of those that would be written about Mance over the next several years. Mance’s soon-to-be fans were well-meaning and enthusiastic, but there were still a few furrows and a turnrow separating their lives from the person who had worked those fields.

Strachwitz and McCormick had recorded Mance performing over twenty songs, including “Tom Moore’s Farm” and the fourteen tracks that became Mance Lipscomb: Texas Sharecropper and Songster. Mance didn’t care for the sharecropper part; he was a farmer. The album was Arhoolie Records’ first release. The record was sent out into the world that November with an initial pressing of 250 copies.

Strachwitz and McCormick had recorded Mance performing over twenty songs, including “Tom Moore’s Farm” and the fourteen tracks that became Mance Lipscomb: Texas Sharecropper and Songster. Mance didn’t care for the sharecropper part; he was a farmer. The album was Arhoolie Records’ first release. The record was sent out into the world that November with an initial pressing of 250 copies.

The world that responded to Mance’s album was more populous than his usual precinct. One man with a tractor could accomplish more than twenty men and forty mules, and automation had left the bottomlands nearly depleted of people. Those that remained were scattered out in a few pockets of semi-civilization: 100 at Millican, 75 at Cawthorne, maybe 15 at Allenfarm. Even counting the folks in western Grimes and northern Washington counties, there were probably less than 10,000 people within Mance’s vicinity.

One day short of a year after being “discovered” by Strachwitz and McCormick, Mance performed before 41,000 people at the Berkeley Folk Music Festival. John Bryan, the writer who had described McCormick’s find for the Examiner, tells us that Mance’s delivery was “halting at first” but that “Lipscomb charmed a sophisticated audience with his direct, earthy approach…”

Writing for the Oakland Tribune, Clifford Gessler offered a somewhat mixed review: “His performance, fortified with a deft guitar, carried strong impact, even though, with his Deep South dialect and indistinct enunciation, only portions of the texts were intelligible. He could have gone on all night, and some of us were afraid he would, but his manager eventually called time on him.”

Mance was realistic regarding his showing: “I had forty-one thousand people lookin’ at me… I had the head down, had my hat pulled down over my eyes. And I never did look up, ’cause I was just chilled through… I didn’t know whether the guitar was tuned up or not, I just blammed away on it and try to get something out of it.”

Berkeley, 1961 is the Breakthrough Performance of our biopic, the show that opens all of the doors and a few windows of opportunity. In keeping with the accepted film format, we are obliged to follow the breakthrough with the highlight reel, the montage of concert appearances, press greetings, and fan chases, the clips flashing by as the film’s theme song plays in the foreground. Since the director of our movie is also its writer, I will award myself the privilege of selecting the appropriate theme song: “Careless Love,” from Trouble in Mind, Mance’s second album. The LP appeared on Reprise, the label of Frank Sinatra, which was looking to take advantage of the flourishing folk music revival.

Mance’s early performances included: in 1962 Del Mar College in Corpus Christi and the University of Houston (appearing with Lightnin’ Hopkins); in 1963 the University of Texas, the Berkeley Folk Music Festival (with Sam Hinton, Jean Ritchie, and Pete Seeger), the UCLA Folk Music Festival (with Seeger, Hinton, and Bill Monroe), and the Monterey Folk Festival (with Peter, Paul and Mary, the Weavers, and an about-to-turn-22-year-old Bob Dylan making his first appearance on the West Coast); in 1964 the Outdoor Art Club in Mill Valley, the Cabale Creamery in Berkeley, the University of Houston (with Lightnin’ Hopkins and Bonnie Dobson), the Summer Music Festival in Austin, Texas (with Lightnin’ Hopkins and John Lomax, Jr.); and in 1965 the University of Chicago, the Brandeis Folk Festival, and the Newport Folk Festival, remembered for the concert at which Bob Dylan was booed for going electric.

A review of the 1963 Monterey Folk Festival by now-noted jazz critic Richard Hadlock (who turned 92 this year) observed that “Bob Dylan, who is 21, is neither a great singer nor an outstanding guitarist, but he writes extraordinary social protest songs that are already becoming standards in folk circles.” Hadlock goes on to say that “Mance Lipscomb, Clarence Ashley and Roscoe Holcomb represented — with impressive vigor — America’s older musicians… and helped save the festival from the schoolboys.”

A review of the 1963 Monterey Folk Festival by now-noted jazz critic Richard Hadlock (who turned 92 this year) observed that “Bob Dylan, who is 21, is neither a great singer nor an outstanding guitarist, but he writes extraordinary social protest songs that are already becoming standards in folk circles.” Hadlock goes on to say that “Mance Lipscomb, Clarence Ashley and Roscoe Holcomb represented — with impressive vigor — America’s older musicians… and helped save the festival from the schoolboys.”

Asked about Dylan in a 1966 article for the Austin American-Stateman, Mance said, “That young kid, Dylan, he’s a real nice young fella. He’s written some real good songs, too. I’m crazy about them. He used to follow me around out in California when I was playing there a few years ago. He’d be real quiet and just watch. You know, he’s a quick boy to catch on.”

Mance’s fame got an early boost from a two-page article by Pete Welding in the February 10, 1962 issue of the widely-read and influential Saturday Review. As with most of the articles written about Mance back in the day, it is discomfiting to read phrases such as “…the whole broad complex of song styles the Negro had evolved in the New World.” But Welding, who was nominated for a 1993 Grammy award for writing the liner notes included in Roots ‘n’ Blues: the Retrospective (1925-1950), praised Mance as a “master songster” whose “gripping, intense, and infectious work restores to currency a sound long absent from the land — the sound of the songster in all its rich variety and expressive power.”

Welding’s article led directly to Mance’s appearance at Del Mar College in Corpus Christi, his fourth concert and his first at a Texas university. “‘But don’t give us too much credit,’ said Dr. Vernon Lynch, professor of English in charge of the program. ‘We discovered him in the Saturday Review.'” Tickets for the show were available at local bookstores and record shops, and from the English professors, for 75 cents. Adjacent to the Corpus Christi Caller-Times article announcing the concert, we find an advertisement for a Hand Crafted Zenith television with No Printed Circuits, available from Acme Radio and TV for only $169.95.

As a measure of how quickly Mance became an established musical presence, a year after the release of Texas Sharecropper and Songster, Ralph Gleason, later a founding editor of Rolling Stone, complained in a syndicated column that Mance Lipscomb would have been a better choice to represent folk music at a fundraiser for the National Cultural Center (later the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts) than the organizers’ choice: Harry Belafonte, whose picture was captioned No Folk Singer.

Whatever nervousness Mance possessed at his first Berkeley appearance had vanished within a few years. In “Take Your Arms from Around My Neck,” recorded at the 1966 Berkeley Blues Festival, Mance is clear-voiced, confident, and relaxed. It’s easy to imagine Mance playing this song, with it’s thumping bass and lively treble strings, on a Saturday night in a room illuminated by homemade kerosene lamps, as a noisy crowd dances on an unvarnished wooden floor.

V. The Ether

You can live in heaven here on earth. Peaceful and quiet and nice to people. The way you live, the way you die. If you live good, you die good, in a peaceful way. I just know the day comin’: I’m gonna die. But I don’t know how soon. And I don’t know how long it’ll be, and how I’m gonna feel when I die ’cause I never have died. I don’t know how it feels. — Mance Lipscomb, A Well Spent Life

Mance Lipscomb continued to tour and perform until January 1974, when he suffered a stroke. His discography includes seven full-length albums and numerous compilations. He was the subject of a film by Les Blank, A Well Spent Life, shot around Navasota in 1970 and released the following year. In the frames we see a slight but upright man, a philosopher of quiet strength. In 1973 Mance dictated his biography to Glen Alyn in a series of go-alongs that became I Say Me for a Parable.

Mance Lipscomb died in Navasota on January 30, 1976. Thirty-five years later, a statue of Mance was placed in Navasota’s Mance Lipscomb Park. He and Elnora are buried in the Rest Haven Cemetery.

A Note on Quotations: Most of the quotations by Mance Lipscomb were borrowed from I Say Me for a Parable. The book was created by recording Mance in a series of stream-of-consciousness go-alongs, which were compiled, transcribed, and edited by Glen Alyn. Alyn attempted to capture the sound of Mance’s words: fawma for farmer, gittah for guitar, Mow for Moore, tamarra for tomorrow, etc. But, having heard Mance speak in films and in concert recordings, I believe Alyn’s renderings were unnecessay and excessive. Mance definitely spoke like someone who was born and raised in the rural south. He sounds a lot like my (white) aunts and uncles who were farming in some rocky Tennessee soil around the same time that Mance was farming in Texas. As someone who grew up hearing the speech of country people, white and Black, I didn’t find Mance’s pronunciations to be amazing. Therefore, I’ve changed the spelling of many words from I Say Me for a Parable. I tried to capture the character of Mance’s speech rather than the exact sounds of the words.

A Note on Thirds and Fourths: In the seventh go-along of I Say Me for a Parable, Mance describes thirds and fourths thusly: “And havin’ my own team, that brought me up to thirds and fourths: every third load of corn, and every fourth bale of cotton, well that was the landowner’s.” But in the introduction to the chapter, Alyn swaps the portions, defining rent farming as “having to give the landowner every third bale of cotton and every fourth bushel of corn.” Mack McCormick, in the liner notes for Mance’s first album, also defines the rent as 1/3 cotton and 1/4 corn. Looking farther afield, the Texas State Historical Association tells us, “Share tenants typically paid the landlord a third of the cotton crop and a fourth of the grain,” while the Oklahoma Historical Society maintains that “In the usual arrangement with share tenants in Oklahoma, the landlord received one-third of the grain crop and one-fourth of the cotton produced.” I’m sticking with Mance’s definition, but I’m happy to assume that the proportions of cotton and corn paid as rent probably varied among locations and possibly from farm-to-farm.