Chicago

Chicago, when the wind from the West set in, had an unmistakable odor of burning pork.

— Thomas Wolfe, Oktoberfest

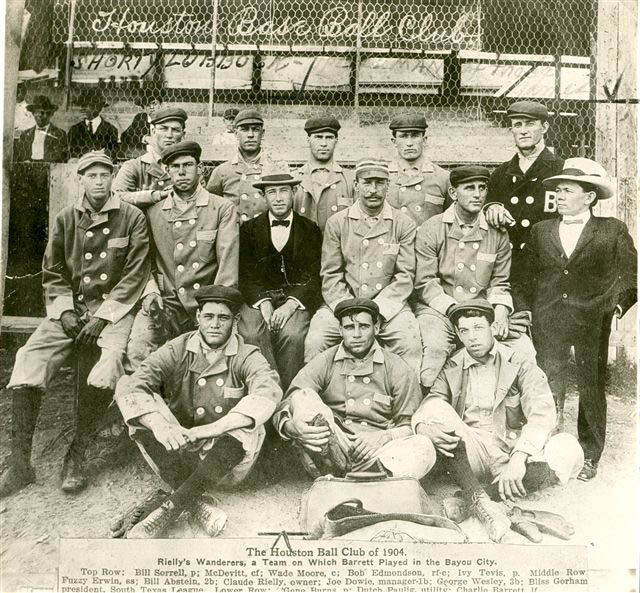

Between the 1885 and 1886 seasons, Cap Anson starred in a touring play called A Runaway Colt, a farce written by Charles H. Hoyt, who died insane in 1900. “The story tells of a young college graduate, the son of a minister, who becomes a noted pitcher of the college club,” a reviewer explained. “He then wishes to become a professional, but is opposed by his parents, runs away from home, and under an assumed name becomes one of Anson’s Colts.”

Poster advertising “A Runaway Colt,” 1895. Heritage Auctions.

Poster advertising “A Runaway Colt,” 1895. Heritage Auctions.

In the screenplay based on this book, Johnny Corbett learns of Cap Anson’s plans for a semi-pro baseball team in early 1907 and vows to play for the greatest manager in baseball history. He tells his mother he is off to Chicago to seek fame and fortune on the baseball diamond.

Tears and harsh words ensue until James Corbett enters the cramped country kitchen (for the sake of a feel-good narrative, we will resurrect Pater Corbett and replace his pinstriped gambler’s coat with the somber vestments of a Midwestern minister). The good pastor takes his son out behind the barn and forks over the coins for a one-way ticket to Chicago’s Union Station along with some tough-love fatherly advice: “Don’t come back until you make good.”

Johnny Corbett shows up at a Colts practice in Anson’s Park, introduces himself as “Jack,” pulls a battered glove from his back pocket, and convinces team captain Lou Gertenrich to hit him a few grounders. Gertenrich insists the youngster is “wasting your time and everyone else’s.”

With Anson watching from a distance, Corbett proceeds to wow the players with his foul-line-to-foul-line range and whip-like arm, scooping up everything Gertenrich sends his way and firing the balls to first base, where they pop into first baseman Al Weinberger’s mitt.

When Corbett trots in from the diamond, Cap Anson himself greets him and hands the youngster a brand-new jersey with Anson emblazoned across the front in Old English script. “Welcome to Chicago,” Anson beams down at his new disciple.

And who can say it didn’t happen that way?

The circumstance that plucked Johnny Corbett off the scratchy infields of eastern Indiana and deposited him on the semi-pro diamonds of Chicago remains a mystery. All we can say with certainty is that when Anson’s Colts played their first game on Saturday, April 20, 1907, John Corbett, now known as “Jack,” batted third and played shortstop. He remained with the Colts for the entire 1907 season.

Corbett’s connection to the Colts may have been third baseman Hugh Cook. Cook was an Indiana boy, born and destined to die in Kewanna. Like any good ballplayer, he would have kept his ear to the baseball grapevine, always aware of the talent circulating in the sticks. He may have recommended Corbett to Anson and Gertenrich.

Batting third in the Colts’ first game, Corbett made no hits but scored a run as Rogers Park corralled the Colts 3-4. He had one putout, two assists, and an error in the field.

The Colts played five games from April 20 through May 12, winning two and losing three. Corbett appeared at short in each game, recording five putouts, eight assists, and three errors. At the plate, he tallied four hits and four runs.

The previous October, the American League’s Chicago White Sox, known as the Hitless Wonders, had upset the National League’s Chicago Cubs, featuring Tinker to Evers to Chance, in the World Series. The White Sox celebrated their victory on Tuesday, May 14, 1907, with a banner-raising ceremony before a game with the Washington Senators.

Chicago Mayor Fred Busse began the day by naming a special commission to investigate Chicago’s air pollution problem. Under the headline WAR DECLARED ON SMOKE, the Chicago Tribune optimistically predicted that “Grimy Chicago, second only to Pittsburgh in its destruction of health and clean linen, will soon be a thing of the past.”

After lunch, Busse and Chief of Police George Shippy descended the steps of City Hall and climbed into a gaily decorated automobile along with White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. The trio led a parade that snaked down to South Side Park on 39th Street between Wentworth and Princeton.

“Everybody from Mayor Busse down to the lowest scrubman in the building was out in the parade,” Tribune columnist Sy Sanborn reported. “Every automobile and nearly every horse drawn craft in Chicago seemed to have been impressed into service.”

The Chicago White Sox players followed the VIPs and politicians. Chicago’s semi-pro teams sent a strong contingent. Riverview Park’s motor coach carried the team owners, fourteen uniformed players, seven umpires, and twenty assorted fans and friends. Jimmy Callahan packed his Logan Squares into a pair of automobiles.

More autos conveyed the Spaldings, Artesians, West Ends, Lawndales, Fortunes, Topazes, Roxburys, Clover Leafs, and Anson’s Colts – with one car presumably bearing Jack Corbett. Teams that were unable to hire automobiles tagged along in streetcars. The Stockyards Boys, a wild delegation of more than thirty cowboy-hatted horsemen, brought up the rear.

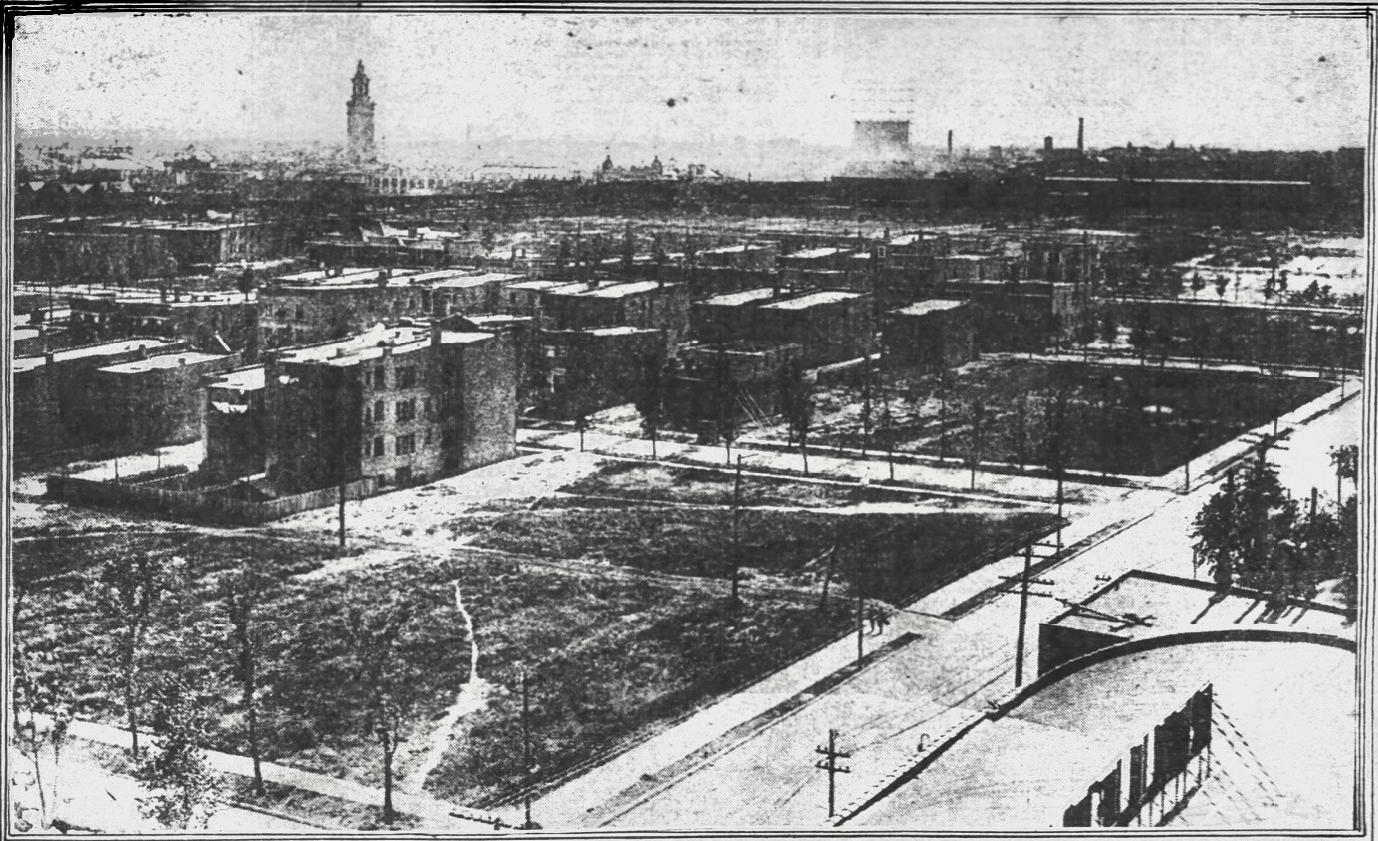

The Stockyards Boys in the parade to South Side Park. Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1907.

The Stockyards Boys in the parade to South Side Park. Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1907.

In South Side Park, a full house of over 15,000 fans awaited the procession beneath a blanket of black clouds. The first car shot through the gate at 2:40 PM and led the parade in a lap around the ballpark. Ten minutes elapsed as the contingent entered the grounds.

The crowd cheered its collective head off as the occupants of the vehicles waved White Sox flags and pennants. Even the semi-pro players received a share of the adulation. After completing their circuit, the cars and coaches pulled out of line and parked all over the field. Recent rains had softened the dirt, and many tires sank into the mud.

Comiskey, Mayor Busse, and Chief Shippy stood in the outfield and unfurled an enormous purple and gold silk banner that proclaimed the White Sox to be World Champions. The flag’s length was greater than the depth of the outfield bleachers. They held it aloft and marched up to the grandstand as Big Bill Thompson, a former County Commissioner and future Mayor, called for nine cheers: three for Comiskey, three for Busse, and three for the White Sox players. The Stockyards Boys galloped through the gate and thundered around the field as the cheers echoed through South Side Park.

After the requisite speeches, Comiskey, Busse, and Shippy carried the banner back to center field, where the White Sox players awaited. The Stockyards Boys surrounded them in a half-ellipse of men and horseflesh as the players prepared to raise the banner to the top of the flagstaff. The banner was attached to the halyard, and the players heaved like a crew of flannel-clad pirates hoisting the fore topgallant staysail.

White Sox players hoist the pennant in South Side Park surrounded by the Stockyards Boys. Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1907.

White Sox players hoist the pennant in South Side Park surrounded by the Stockyards Boys. Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1907.

The stately pine flagpole, a veteran of seven seasons of Chicago’s winds and winters, was implanted several yards behind the bleachers. The players were positioned in front of the bleachers rather than at the base of the staff, where they would not be visible. Their heaving, then, was more horizontal than vertical.

The banner’s tail had not cleared the ground when the pole snapped. It tottered, threatening the lives of the bleacherites below, then fell harmlessly to the side. It was a sure sign that God is a Cubs fan.

While someone hastily secured the banner to a liquor advertisement in right field, White Sox pitcher Nick Altrock lightened the mood by commandeering a horse and leading the Stockyards Boys on a merry chase, finally being brought to bay in front of the grandstand.

Altrock dismounted the horse, climbed the mound, and prepared to pitch to the Senators. The cars were herded out the gate, though several large autos remained parked along the outfield fence.

Altrock faced four batters, one reaching base when the ball caromed away from the fielder after hitting a tire rut left by a departing auto. The clouds opened as the teams exchanged places between innings, and a deluge ended the game.

The cars that had remained on the field became hopelessly mired in the muck. They were extracted by a team of dray horses, leaving behind a month’s work for Groundskeeper Reuter.

The Tribune’s Sy Sanborn summarized the celebration: “Chicago, always doing something notable, had broken another world’s record by pulling off a pennant raising without raising a pennant or playing a ball game.”

The afternoon’s festivities may have been the greatest spectacle thus far witnessed by the young Jack Corbett. He wasn’t in Indiana anymore. Just 19 years old, he was almost in the Big Show, close to World Series banners, cars full of important men, cheering crowds, and the great Cap Anson.

Corbett began the season batting third, then moved up to the two-hole. In a May 12 game against the Marquettes, Corbett smacked a double and scored two runs as the Colts won 7-4. The effort earned Corbett a promotion to cleanup.

Facing the Oak Leas on Saturday, May 18, Corbett bagged two hits and two runs in a 19-3 Colts win. On Sunday, he added two more hits in a loss to the River Forests.

Corbett’s batting average is impossible to calculate with precision. Box scores are available for 44 of the 46 games Corbett played, but none of the tables list at-bats. We can approximate his batting average by making an educated guess of 3.5 at-bats per game. By this estimation, Corbett was batting a respectable .286 after the game against the River Forests.

Corbett was not a power hitter. But throughout his career, his bat carried enough pop to earn him frequent stays in the meat of the order. In an era when almost all home runs were of the inside-the-park variety, Corbett’s speed and ability to make contact made him an excellent choice for batting third, fourth, or fifth.

Decoration Day, May 30, fell on a Thursday in 1907. President Roosevelt spent the afternoon playing baseball in a farmer’s field outside Akron while Vice President Charles W. Fairbanks watched from the comfort of a fence rail. Schools and businesses all over Chicago closed down, and the semi-pro parks opened up for business.

Corbett’s short stint as a cleanup hitter ended that afternoon when he turned in an oh-fer against the Pirates, a traveling team with an unimpressive record. He dropped down to the five spot, remaining there for most games until late in the season.

Corbett missed his only game with Anson’s Colts on Sunday, June 2. Kid Puls, an Anderson boy who had briefly handled the third base chores for Willis McDonnell’s Winchester team in 1906, replaced Corbett at shortstop. He performed well, bagging two hits, a run, three putouts, and three assists, then vanished from the box scores.

On Saturday, June 8, Corbett starred in the field with three putouts, five assists, and no errors as the Colts lost to the All Havanas 5-7 in 12 innings. The next day, he had another solid performance against the White Rocks with four putouts and two assists.

Corbett’s excellent shortstop play continued the following week. The Colts downed the Leland Giants and Oak Leas, with Corbett compiling three putouts, eight assists, and a single error,

Jack Corbett was probably paid about $15 weekly for playing two games, one on Saturday and another on Sunday. It wasn’t a lot of money – a union hod carrier in Chicago made $16.80 weekly – but it was the going rate for semi-pro players who played only on weekends.

He may have commuted between Anderson and Chicago. But if he chose to stay in the city during the week, there were plenty of attractions for a young man on a budget.

He could take the cars to the Cubs’ West Side Park and watch shortstop Joe Tinker and second baseman Johnny Evers scoop up grounders and fire them to Frank Chance at first. Or he could visit South Side Park and cheer for White Sox shortstop George Davis, a future Hall of Famer who would die in a mental institution suffering from syphilis.

Sans Souci Amusement Park lay three blocks northwest of Anson’s Park at the corner of Cottage Grove Avenue and 60th Street. The park featured a scenic railway, a roller coaster, a shoot-the-rapids ride, a roller skating rink, a vaudeville theater, and a band directed by Francesco Ferullo.

The Airships ride, near the corner of Cottage Grove and 61st, became Sans Souci’s featured attraction. Passengers rode four dirigible-like pods raised and lowered by a rotating steel tower. The structure was visible from Anson’s Park. Standing at his shortstop position, Corbett could see the tower to his left, rising beyond the buildings along Champlain and Langley Avenues.

A 10-minute walk southwest from Anson’s Park brought one to the White City Amusement Park, constructed in 1905 on a 14-acre cornfield at 63rd and South Park. The 10-cent admission price opened a world of wonders for the visitor’s enjoyment, including such dubious attractions as a small city manned by performers with dwarfism and a building full of premature babies in incubators.

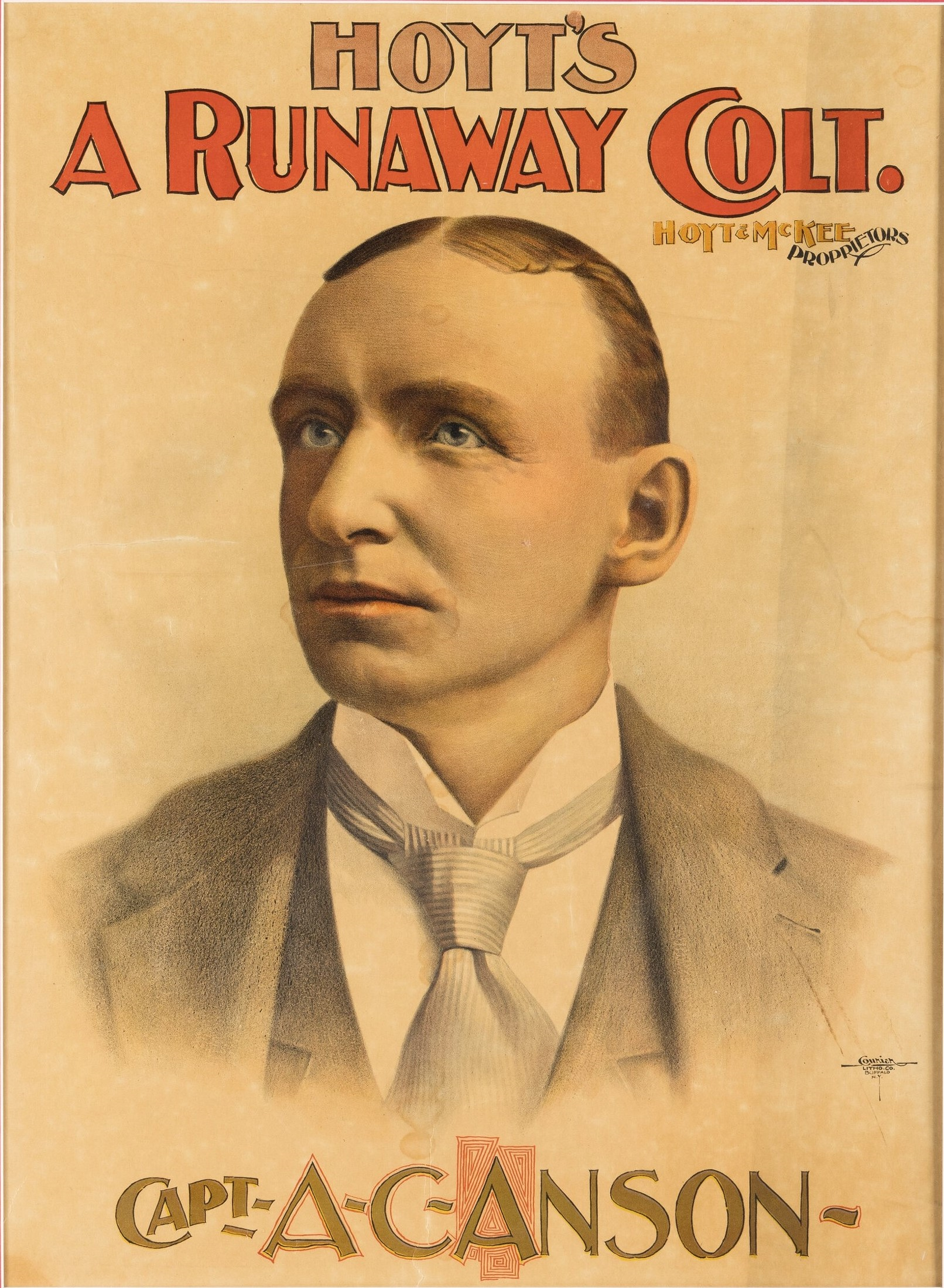

Photograph taken from the Sans Souci Airships ride, looking southwest toward the White City Amusement Park tower (upper left). The intersection at the bottom of the picture is the corner of Cottage Grove (left) and 61st (right). Chicago Inter Ocean, July 18, 1909.

Photograph taken from the Sans Souci Airships ride, looking southwest toward the White City Amusement Park tower (upper left). The intersection at the bottom of the picture is the corner of Cottage Grove (left) and 61st (right). Chicago Inter Ocean, July 18, 1909.

The Chicago Aero Club built an aerodrome adjacent to White City at South Park and 65th. Beginning on May 25 and continuing for two weeks, the aeronauts held balloon and dirigible races each afternoon, provided the wind was not too high.

The “rubber cows,” as the early dirigibles were known, comprised a silk bag filled with hydrogen. A spindly spruce frame dangling below the bag held the pilot, a small motor that turned a propeller made of canvas stretched over spruce supports, and a rudimentary rudder made of spruce and muslin.

The pilot controlled the airship’s pitch by moving fore and aft along the narrow lattice. Pilots often packed an extra rudder since they tended to snag on trees and telegraph lines. The airships lacked an internal structure. Though always referred to as “dirigibles,” they would today be classified as blimps.

If Corbett wandered over to the aerodrome after a game, he might have encountered Horace B. Wild, who had been piloting his airship Eagle through Chicago’s skies for at least a year. Wild and Corbett would cross paths in Anderson, South Carolina, three years later.

Horace B. Wild flying the Eagle over Chicago in 1906.

Horace B. Wild flying the Eagle over Chicago in 1906.

Photographer George R. Lawrence had a studio at 63rd and Yale. He was an enthusiastic follower of the aviators’ activities. Lawrence combined his profession with his love of flight to become a pioneer in aerial photography.

After the San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906, Lawrence used kites to send a camera 2000 feet above the bay and captured a 160-degree panorama of the still-smoldering devastation. The photo became world-famous, and the reproductions earned Lawrence over $15,000, nearly half a million in today’s dollars. Lawrence later started an airplane company, though his designs did not succeed.

San Francisco in Ruins. George Lawrence, May 28, 1906.

San Francisco in Ruins. George Lawrence, May 28, 1906.

First baseman Al Weinberger made his final appearance with the Colts on June 30. Before that date, George Lawrence snapped a photo of the 1907 Anson’s Colts. Weinberger stands in the back row to the right of Cap Anson.

Photograph of Anson’s Colts taken by George R. Lawrence before June 30, 1907.

Photograph of Anson’s Colts taken by George R. Lawrence before June 30, 1907.

Jack Corbett sits on the floor at the far right of the front row. His spikes, shiny and sharpened, dig into Mr. Lawrence’s already-frayed rug.

The son of a gambler and a corsets saleswoman, Corbett is surrounded by college graduates, professional men, and two men – Anson and Walter Eckersall – who were nationally famous. If he felt any shade of intimidation, it was not evident in his punkish pose and sultry expression.

Corbett found his stride in mid-June, and his name began to appear in the newspapers. On Saturday, June 22, the Colts beat Gertenrich’s old Rogers Park team. Corbett knocked a single and a double, scored two runs, and made a putout and six assists, including two Corbett-to-Rooney-to-Weinberger double plays. “Corbett and Rooney played fine ball on the infield,” the Trib noted.

The young shortstop turned in another solid game the following day. In a 10-inning loss to the Elgin Nationals, he had a double and two singles, scored two runs, and made three putouts and seven assists with no errors. Corbett’s estimated batting average was now a solid .343.

On Sunday, June 30, the Colts downed the Spaldings 9-2 in Al Weinberger’s final appearance, with Corbett bagging three hits and scoring two runs.

Following the game against the Spaldings, Corbett owned an excellent estimated batting average of .353. After that, his average steadily declined as an increasing sample size caused the inevitable regression to the mean. His final 1907 estimated average, .266, was nearly identical to his career minor league average.

The Illinois Industrial School for Girls had operated in Evanston since 1877. “On the first of November we announced our readiness to receive, gratuitously, all the destitute, homeless, and dependent girls who were sound in mind and body of whatever nationality or creed, and guaranteed to give them instruction in all branches of domestic labor, and, as soon as practicable, lucrative trades, also instruction in the common English branches,” wrote Mrs. Louise Rockwood Warner, the institution’s first president, when the school opened its gates.

Despite its grand name and lofty intentions, the Illinois Industrial School for Girls was an orphanage where, a 1906 investigation revealed, “the girls receive no industrial training whatever, other than such as might be gleaned from doing household work in the institution.”

The school was nearly bankrupt by 1907. The monthly deficit, attributed to “extravagance and incompetency,” exceeded $500. The 125 orphan girls who lived at the school, ages 5 to 15, were in danger of being sent to the Cook County almshouse. To raise money for the school, the ladies of Chicago society organized a Civic Ball Game: Anson’s Colts and the Gunthers would square off at the Cubs’ West Side Park on Wednesday afternoon, July 17.

The winning team would take home the Busse Cup, a silver trophy donated by Chicago Mayor Fred Busse. The Mandel Brothers’ silver shop forged the cup and displayed it in their store window during the week leading up to the event. “It stands a foot high on its ebony base,” the Inter Ocean reported, suggesting an unimpressive prize by modern standards. On the day of the game, the cup journeyed to West Side Park on the front seat of a Hebard bandwagon, with a band in the rearward seats blowing heroic marches.

A month before the game, a Tennessee minister declared, “Hell is a place of strong drink, tobacco, baseball, theaters, and peekaboo shirtwaists.” All were present, in varying degrees, at the Busse Cup game.

The peekaboo shirtwaist was a blouse made of a light material inset with coarsely crocheted lace that created holes adequate for access by a mosquito. Some designs featured sleeves that extended only to the elbows. The blouse left everything to the imagination, but Late Victorian gentlemen were shocked by the fantasies the shirtwaists incited in their own minds.

Many offices banned the peekaboo shirtwaist, and several state legislatures considered outlawing them. A popular joke ran, “I was talking to a peekaboo shirtwaist girl, and I was so embarrassed, I couldn’t look her in the face.”

With afternoon temperatures in the high 70s, the West Side Park crowd displayed a plethora of peekaboo shirtwaists. The wearers included eight chorus girls borrowed from a local theater to sell scorecards.

The writer for the Inter Ocean, a staunch Republican rag, could hardly contain himself: “With broad hats, spreading smiles, peekaboo waists, and manners that were calculated to increase the sale of the score cards, they waylaid the charitably inclined at the gates and pursued them to their shaded seats in the grandstand, urging them to buy.”

One scorecard seller accosted Cap Anson, who posed for a photograph in the act of purchase. He fished a dollar bill out of his pocket – an extraordinary sum for a scorecard – and found himself surrounded by the entire chorus line. Anson eased from the flouncy scrum without further investment.

Cap Anson surrounded by chorus girls selling scorecards. Chicago Inter Ocean, July 18, 1907.

Cap Anson surrounded by chorus girls selling scorecards. Chicago Inter Ocean, July 18, 1907.

The Inter Ocean’s man surveyed the scene as over 3000 spectators, most members of Chicago Society, filled the grandstand: “There were white dresses and spotted dresses and pink dresses, and every kind of dress that ought to be worn to a ballgame played in the interests of charity, and there were green hats and red hats and hats with unknown varieties of seaweed on them, and parasols, and opera glasses, and an abiding, sustaining sense that they were there for charitable reasons.”

While the Inter Ocean’s reporter fixated on the ladies in the crowd, the Trib’s man reported that more than 100 boys from the orphanages in Glendale and Allandale attended and “shouted themselves hoarse over the game.”

Anson acted as the celebrity umpire, a role that hindered his proclivity to kick over balls and strikes.

Some semi-pro players, stuck in their real jobs, failed to attend the weekday afternoon game. Corbett seems to have been loaned to the Gunthers to fill out their squad. No one bothered to file a box score to confirm the lineups, but the Trib’s reporter praised “the shortstop work of Corbett” as one of “the features of the Gunthers’ playing.”

Jack Corbett was on a team owned by the great Cap Anson. He was playing in a major league ballpark, being cheered by small boys and girls in peekaboo blouses, scooping up grounders from the same dirt as Cubs shortstop Joe Tinker. He was still two weeks from his twentieth birthday.

Corbett surely envisioned a bright future for himself as a baseball player. He undoubtedly assumed that he would return to West Side Park after a couple of seasons in the minors. Corbett to Evers to Chance had a nice ring to it. But the Civic Ball Game probably marked the last time Corbett would roam a major league park as a player.

Anson’s Colts won the day, 7-1. After the final out, Anson led his team to the grandstand for the trophy presentation. Mayor Busse, unable to attend, delegated Corporation Counsel Edward J. Brundage to appear in his place.

Brundage delivered a brief lecture in which he graciously encouraged Anson’s Colts “to honor the name you bear as your distinguished captain has honored himself on the field.” Anson promised that his players would always adhere to a high standard. The afternoon of Civic Baseball ended, having raised $4000 for the orphanage.

Jimmy Callahan’s Logan Park hosted Semi-Pro Field Day on the third Sunday in July, pitting Chicago’s semi-pro players in feats of strength and ability. Walter Eckersall and Louis Gertenrich represented Anson’s Colts.

Eckersall placed second in the 100-yard dash, first in the “running to first base” competition, and second in the “running around the bases” contest. Gertenrich placed third in “running around the bases,” not bad for a 32-year-old, and won the fungo hitting contest by whacking a fly ball 438 feet.

Following Field Day, the Colts returned to Anson’s Park, where they lost to the River Forests 6-8 in ten innings. The Colts now owned a middling 14-12 record.

Saturday, July 27, was a banner day in the history of Chicago sports: in an afternoon game against the Artesians, Cap Anson squeezed into a baseball uniform and stood in the third base coach’s box for the first time since 1898.

Cap Anson coaching third base at Anson’s Park. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Cap Anson coaching third base at Anson’s Park. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

The Colts responded to Anson’s hands-on coaching by beating the Artesians 8-7. Corbett had three hits, one a double, and scored four runs. Eckersall had three hits and scored a run. “The hitting of Eckersall and Corbett was the feature,” the Trib reported.

In the field, Corbett had two putouts, three assists, no errors, and helped turn two double plays. Corbett was holding his own, and more, with Chicago’s semi-pro players.

Corbett’s hitting against the Artesians earned him a trip back up the order to the cleanup role for the games played the first weekend in August.

In Saturday’s game against the Lawndales, played the day after he turned 20, Corbett committed a critical twelfth-inning error that resulted in a 2-4 loss for the Colts. The Colts trounced the White Rocks 10-3 the next day, but Corbett copped an oh-fer and committed two more errors.

Following his poor performances in the field and at the plate, Corbett returned to the five spot in the order and moved to second base. Eckersall transferred from right field to shortstop. Rooney and Cook alternated at third.

Corbett played his initial game at second base on Saturday, August 10, in Anson’s Park against the West Ends. The bottom of the ninth opened with the score tied 3-3.

With one out and no one on base, Corbett sent a routine grounder to short. The West End fielder scooped up the ball and fired it so far over the first baseman’s head that Corbett made it to third. The next batter, catcher Mike Sampson, poled a long fly, and Corbett trotted home with the winning run. At second, he contributed a pair of putouts and four assists with no errors.

The Colts beat the Oak Leas 5-4 on Sunday to close one of five two-win weekends recorded by the club that season. Corbett chipped in a hit and a run, five putouts, an unassisted double play, two assists, and an error.

The August 11 win against the Oak Leas marked the high-water mark of the Colts’ season. They had won eight of their last ten games, giving them a 19-13 record. But the Colts lost both games in each of the following two weekends.

Future Hall of Fame pitcher Rube Foster led the Leland Giants into Anson’s Park on Saturday, August 24. Foster handled the Colts easily, and the Giants took a 7-1 win. Corbett, like all but two of his teammates, had no hits.

Corbett moved to first base for the next game, displacing James Kiely, who had previously displaced Weinberger. Kiely, batting eighth, was struggling at the plate. The shift allowed Anson to get both Rooney and Cook on the field. With Corbett at first, Rooney at second, Eckersall at short, and Cook at third, the Colts may have had the fastest infield in semi-pro Chicago.

First baseman Corbett had nine putouts and committed no errors in the Sunday game against the Pirates. At the plate, though, it was another oh-fer. The Colts lost 5-10, their fourth loss in a row. Corbett remained at first the following weekend as the Colts beat the Normals but lost to the South Chicagos.

Labor Day brought moderate temperatures to Chicago, with a high of 76 degrees. It was a pleasant respite from the previous day when the mercury climbed to 92. “Yesterday was the hottest Sept. 1 that has ever been known in Chicago since the local bureau began to inform the citizens of their miseries,” the Inter Ocean reported.

Federation of Labor President John Fitzpatrick canceled the Labor Day parade, a showcase of union strength for over a decade. He urged workers to spend the day with their families in a “safe and sane celebration” instead of in the drunken revelry that usually accompanied the procession.

Not all union men passed the day in rest, though. An organizer boarded each streetcar and demanded that the driver and conductor show their union cards. The organizers verbally assaulted non-union employees and ordered the passengers from the cars.

The harassment was especially sharp on lines that served the northwest side, where 3000 socialists had gathered for their annual picnic. Any driver or conductor who consented to join the brotherhood received a pocketful of cheap cigars.

A pair of Labor Day games marked the return of Jack Corbett to the shortstop position, with Eckersall again banished to right field.

Over the seven games Eckersall spent at short, he averaged two putouts, two assists, and 0.3 errors. For the games Corbett played at short in 1907, he averaged two putouts, three assists, and 0.6 errors. Corbett’s advantage in assists suggests that he covered more ground than Eckersall. He made more errors than Eckie but accepted more chances, chasing down balls that lesser fielders would allow to roll through unchallenged.

Though Eckersall had the edge in pure speed, Corbett was Anson’s best shortstop. And as much as the captain may have wanted to showcase Eckersall, he was too good of a baseball man to leave an inferior player at such an important position.

While the socialists were redistributing their Borodinsky bread, the Colts rode the union-staffed streetcars to Normal Park, where they took the morning game 5-1. They climbed back onto the cars for the trip to Gunther Park, where they lost 2-3. In the latter game, Corbett demonstrated his talent at shortstop, snagging four putouts and two assists with one error. The Labor Day results left Anson’s Colts barely above .500 with a 21-19 record.

The game against the Gunthers saw the first appearance of pitcher Eddie Stack, who would later spend parts of five seasons in the majors. Stack became a workhorse for the Colts, pitching in six of their final eight games and compiling a 2-3 record with one no-decision.

The Colts played the Streator Reds in Streator on September 15. A series of field day events preceded the game. “This was originally planned for the Reds alone,” the Streator Times explained, “but they magnanimously permitted the Colts to enter, and the visitors ungraciously took three of the four pieces of the pie.”

Gertenrich won the fungo hitting and “quickest time to first after a bunt” contests. Hugh Cook took the “accurate throwing” event in which players attempted to strike second base with a ball tossed from home plate. A Streator outfielder won the long throw event by heaving the ball from center field and striking the wall fronting the grandstand.

Anson was introduced to the crowd and received a round of applause. Anson’s girth impressed the Times’ writer: “At one time a king bee, Anson is now so portly that he and Big Joe would make a great exhibition in base running.”

Big Joe was Joseph Vyskocil, the Reds’ Czechoslovakia-born pitcher. At six feet, 175 pounds, Big Joe was hardly in the same weight class as Anson.

With Corbett’s batting average below .260, he slipped into the order’s seventh spot. He recorded no hits against Big Joe and the Reds, dropping his estimated average to .250. In the third inning, with the Colts leading 3-0 and two men on base, Corbett struck out to end the inning. The Reds outhit the Colts 10 to 9, but they committed eight errors to the Colts’ one. Eddie Stack got the outs when it mattered, and the Colts won 6-1.

The Colts were scheduled to play in Indianapolis on Sunday, September 21. An article in the Indianapolis News published two weeks before the game claimed that Anson’s Colts were “one of the most widely-known semi-professional teams in the United States.”

The News advertised the Colts as including “Walter Eckersall, of Chicago University football fame,” and “John Corbett,” as he was known in his native land. “Corbett is an Anderson boy, and is well known in Indianapolis, having played in this city,” the News reported.

Corbett’s previous baseball wanderings must have taken him to Indianapolis often enough to make him a known commodity there. If so, his discovery by Anson or Gertenrich might not have been strictly the stuff of a Hollywood screenplay. Baseball men all over the Midwest may have recognized his talent.

The Indianapolis game never happened; “Sunday Baseball” had been illegal in Indiana for years. The Colts instead scheduled a pair of games, played Saturday and Sunday, against the Denver Grizzlies of the Class A Western League.

The Colts took the first game 6-3. Corbett and Henry Butcher were the only Colts who failed to hit safely. Corbett contributed in the field with a putout and six assists. “Two sensational stops by Corbett at short were the fielding features,” The Inter Ocean reported.

The Grizzlies turned the tables on Sunday, downing the Colt 9-6. Corbett took three singles from Grizzlies pitcher Pat Bohannon, a decent hurler who spent six seasons with Class A teams.

The Colts and Grizzlies played a rubber match on September 29. Corbett bagged Bohannon for a pair of singles and added a putout and three assists. The game ended due to darkness, tied 6-6 after nine innings.

The baseball season entered its final inning. High school and semi-pro football games occupied the semi-pro parks. The Eckersalls, an all-star aggregation featuring Walter Eckersall at quarterback, made Anson’s Park their home.

The Colts dispersed after their final match against the Grizzlies then reassembled in Joliet on October 20 for a game against the local semi-pros. Corbett once again batted cleanup.

In the first inning, Gertenrich, batting third, walked, stole second, and went to third on a passed ball. Corbett drove him home with a single to tally the Colts’ first run.

The Colts were leading 9-0 in the middle of the sixth inning, but the Joliets fought back, scoring four runs in the bottom of the sixth and three runs in the ninth.

With two out, a man on first, and the tying run at the plate, the final Joliet batter “cracked a grass cutter to Corbett,” who scooped up the ball and winged it to first for the final out, the last out of the game and the last out of the Colts’ 1907 season.

The 1907 season was a success for Jack Corbett. He proved he had the talent to hang with the best semi-pro players in the nation’s second-largest city. His final batting average, around .266, was respectable. He hit well enough to bat fifth through most of the season. And he played for the legendary Cap Anson, an accomplishment that would highlight Corbett’s resume for the next ten seasons.

Jack Corbett seemed to use Anson as a role model. As a manager, Corbett was a solid baseball man and strategist but became a persistent kicker, unafraid to give any umpire a large piece of his mind. Though Corbett lacked Anson’s proportions, he intimidated umpires who feared that the wiry Corbett might launch a physical attack. Umpires were known to flee the field when confronted by Corbett’s fury.

By November 16, Corbett was back in Anderson. “John Corbett, of Pop Anson’s team, of Chicago, is home for a few days,” the Muncie Star Press reported. The paper also noted the presence of brothers Tom and Bob Fisher. Tom managed the Class A Southern Association’s Shreveport Pirates. His brother, Bob, had completed his second season with a Class D team in Coffeyville, Kansas.

Corbett’s success in Chicago demonstrated that he was ready to play in the minors, and Tom Fisher offered him the opportunity.