Cap Anson and His Great Bankruptcy-Inducing Semi-Pro Ballpark

What I may conclude to do in the future it is hard to say, and if I return again to my first love, baseball, it will not be as a player, but whatever I may be or whatever I may do I shall still strive to merit the approval and good will of my friends – God bless them!

– Adrian C. Anson, A Ball Player’s Career, 1900

Adrian Constantine Anson was born in Marshalltown, Iowa, a town founded by his father on the southwest bank of the Iowa River. The senior Anson became a man of substance with interests in real estate, farming, brickmaking, lumber, and coal.

Young Anson was tall, blond, fair-skinned, and muscular. People in Marshalltown called him “Swede.” Six years after the close of the Civil War, at age 19, he began playing professional baseball with the National Association’s Rockford franchise. His youth and pink cheeks earned him the nickname “Baby.” He played for the Philadelphia Athletics from 1872 through 1875 and served briefly as their player-manager.

Anson joined the Chicago White Stockings of the new National League of Professional Baseball Clubs in 1876. The White Stockings opened their season on April 25 with Anson at third base, beating Louisville 4-0. The Battle of the Little Bighorn took place two months later.

With Anson batting .356, the White Stockings took the National League’s first pennant. Anson split time between third, catcher, and the outfield until mid-way through the 1879 season when he was named Chicago’s player-manager. Anson installed himself at first base, where he remained for 19 years, becoming a titanic figure in the baseball universe.

Anson helped define the modern game. As a major league player, he recorded a career batting average of over .300, accumulated around 3000 hits (experts debate the exact number), tallied over 2000 runs-batted-in, and struck out only 330 times in over 10,000 at-bats.

Anson’s White Stockings won five National League pennants, earning him the title of “Captain” or “Cap.” The newspapers of the day usually referred to him as “Capt. Anson” or “Capt. A.C. Anson” as if he bore a military title. He was an authoritarian manager, disliked by many players but popular with the public.

Anson became an early advocate of spring training, the pitching rotation, using signals between the pitcher and catcher, base stealing, the hit-and-run play, the shifting of fielders to counter a batter’s strength, and the platoon system. He led his players through workouts that promoted complete cardiovascular fitness and demanded that his men behave respectably.

As early as 1887, when Anson was a 35-year-old player-manager leading a team of twenty-somethings, Chicago’s sportswriters called the White Stockings “Anson’s Colts.” The name stuck, and from 1890 until Anson left the club, the team was officially known as the Chicago Colts. The American League’s Chicago franchise later adopted the White Stockings name, shortening it to White Sox.

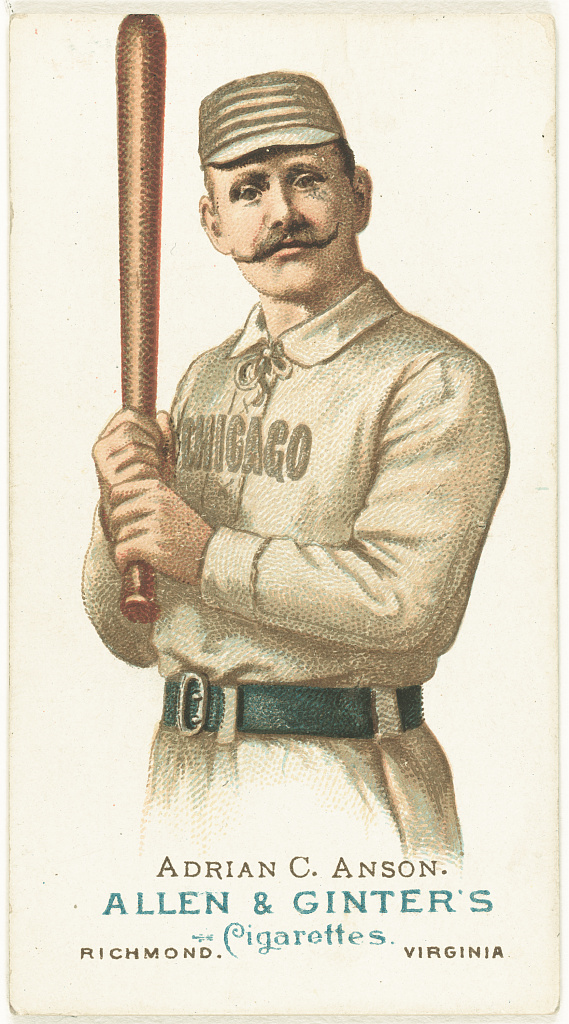

Adrian C. Anson card, Allen & Ginter’s Cigarettes, 1887.

Adrian C. Anson card, Allen & Ginter’s Cigarettes, 1887.

Anson used his physical stature and booming voice to intimidate umpires. He became the “King of Kickers,” complaining and arguing after every adverse call. The endeavor was a hobby for Anson, a sport-within-a-sport played for his amusement.

The Cleveland Spiders entered the National League in 1889. The sportswriters for Cleveland’s Press and Plaindealer got their first view of the King of Kickers in action on a Saturday afternoon in mid-June and were shocked by the spectacle. The Chicago Tribune reported their reactions under the headline ANSON RIDICULED FOR HIS BLUSTER:

“Cleveland has never before witnessed an out and out exhibition of kicking upon Ansonian principles, and the town is just at present trembling between indignation and astonishment at the physical demonstration… The Sunday Press of Cleveland stands shocked at Anson’s conduct, which it characterizes as ‘simply awful.’ Says the Plaindealer: ‘Anson must be losing what mind he ever had. There is method and sense in kicking on close plays. Such kicks affect the feature and pay for themselves. Kicks at umpires make them careful on succeeding plays. But in this game Anson blustered and bullied without purpose. He kicked on open plays, balls, strikes, and everything each inning… Even his own men were deriding him during the game. It was awful.’”

As Anson’s fame grew, the fame of his mustache followed. When Anson pruned the shrubbery in 1895, the news made headlines on sports pages nationwide.

“The mustache is gone,” columnist O.P. Caylor wrote. “The mustache was only a moderate elongated tuft of hair the color of a yellow dog, but it was national, because it grew on the upper lip of a national character – on the upper lip of the greatest, grandest, oldest and nearest immortal baseball player on the earth. It grew upon that flexible upper lip which during the last 25 years has by its movements and the words which came from beneath made miserable the lives of a multitude of umpires. What sarcasm that mustache in its day and generation roofed! What words of irony and sharp retort it looked down upon as they flew out at the luckless victims!”

Adrian C. Anson, circa 1895. Heritage Auctions.

Adrian C. Anson, circa 1895. Heritage Auctions.

The 45-year-old Anson, now known as “Pop,” was finally forced out of the Chicago franchise after a disappointing 1897 season. Following Pop’s departure, the Colts became the Chicago Orphans for a few years before changing to the Cubs in 1904.

The captain completed his professional baseball career in 1898, managing the New York Giants for 22 games. He retired from the game one week after Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders stormed San Juan Hill. One writer called Anson “the embodiment of the entire history of the game of baseball.”

The game’s history includes Anson’s role in creating professional baseball’s color line. On multiple occasions, Anson threatened to withhold his players from exhibition games against teams that sent Black players to the diamond. Anson may not have been the first to place his bat in foul territory and draw a line in the sand, but his actions are the most disappointing compared to his stature as a player and manager.

The amount of influence wielded by Anson – whether the color line would have existed without Anson’s support – is a matter of modern speculation. But Sol White, a Black player who was a contemporary of Anson’s, laid the blame squarely on the captain’s cleats.

In his Official Base Ball Guide, printed in 1907, White wrote, “His repugnant feeling, shown at every opportunity, toward colored ball players, was a source of comment through every league in the country, and his opposition, with his great popularity and power in base ball circles, hastened the exclusion of the black man from the white leagues.”

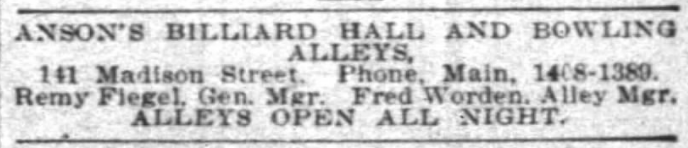

After leaving the major leagues, Anson dabbled in various business schemes as he attempted to translate his fame into dollars. His largest investment was a combination pool hall and bowling alley on Chicago’s Madison Street, which he advertised as the “finest billiard and pool room in the world.”

Advertisement for Anson’s Billiard Hall and Bowling Alleys. Chicago Inter Ocean, October 22, 1905.

Advertisement for Anson’s Billiard Hall and Bowling Alleys. Chicago Inter Ocean, October 22, 1905.

In the 1905 Chicago city election, Anson joined the Democratic ticket as he sought the office of City Clerk, a job with an annual salary of $6000. The city’s streetcar system had degraded into a morass of private lines, and the “traction question” – whether the city should consolidate all lines under municipal ownership – was foremost in the voters’ minds. Anson, however, concentrated his campaign on the issue of “race suicide.”

Race suicide was the belief that the country’s white, native-born, largely Protestant population was allowing itself to be overwhelmed. The large-familied Catholics of Irish and Italian ancestry were of particular concern.

The solution: maintain a higher birth rate than the competition. President Theodore Roosevelt brought race suicide to national attention in 1902 when he declared that someone who deliberately avoids creating children “is in effect a criminal against the race, and should be an object of contemptuous abhorrence by all healthy people.”

Anson told Chicago’s voters that the Democratic candidates for Mayor, City Treasurer, City Attorney, and City Clerk had, between them, fathered 20 children. “A showing like that ought to satisfy President Roosevelt,” he concluded smugly.

Candidate Anson did not impress the editorial board of the Chicago Eagle. “The idea of expecting the people to go wild over the candidacy of a played out professional ballplayer for City Clerk is rich,” the paper printed a few days before the election. “He never did a day’s work in his life.”

Anson’s name recognition put him into office. After the election, a check of the records revealed that he had failed to pay the city’s annual $10 license fee on the 41 pool tables in his establishment. He was $410 in arrears, resulting in the comical scenario of Anson ordering himself to write a check to himself. Anson later appeared before the City Council and unsuccessfully urged them to reduce the license fee on each table to $5.

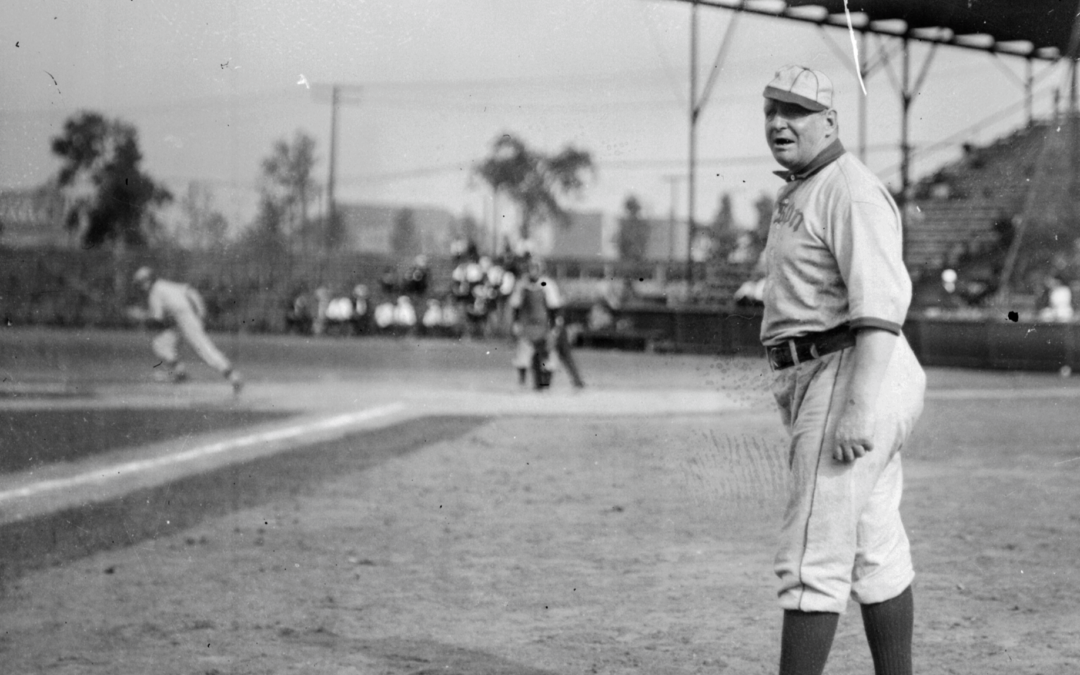

Capt. Anson, possibly in 1907. Bain News Service.

Capt. Anson, possibly in 1907. Bain News Service.

The semi-pro baseball craze swept Chicago in the mid-1900s. A baseball man could make money by building a little ballpark, assembling a fast team to play in it, and charging fans a quarter to watch the show. By 1906, semi-pro teams were in Artesian Park, Rogers Park, South Chicago Park, Normal Park, West End Park, Gunther Park, Northwest Park, White Eagle Park, Gainer and Koehler Park, and New Washington Park.

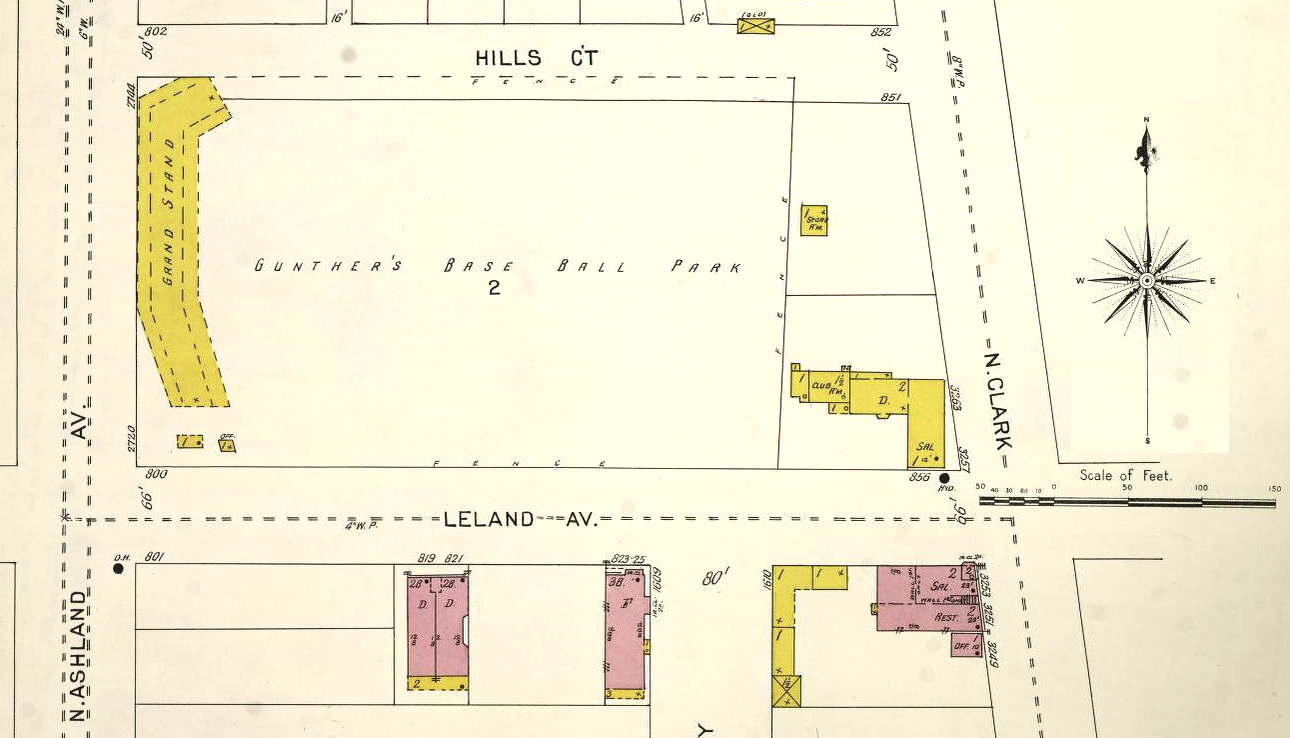

Gunther Park, a typical Chicago semi-pro ballpark. The tract was about 260 x 440 feet. The grandstand was about 225 feet long and 40 feet deep. Sanborn Map Company, 1905.

Gunther Park, a typical Chicago semi-pro ballpark. The tract was about 260 x 440 feet. The grandstand was about 225 feet long and 40 feet deep. Sanborn Map Company, 1905.

Gunther Park in 1913.

Gunther Park in 1913.

Jimmy Callahan, a former pitcher for the Colts and White Sox and a good friend of Anson, had a team in Logan Square Park. Jimmy Ryan, another old Colt, hosted a team in Lawndale Park. The Leland Giants, one of the best Black teams in the country, played in John Schorling’s Auburn Park. Schorling was a son-in-law of White Sox owner Charles Comiskey.

Jimmy Callahan’s Logan Square Park.

Jimmy Callahan’s Logan Square Park.

In February of 1906, Anson announced that he was jumping into the semi-pro business with “a crack team” and had begun leasing ground for his ballpark. Anson did not complete his land acquisition until October 1906, and the team did not manifest itself until the following season.

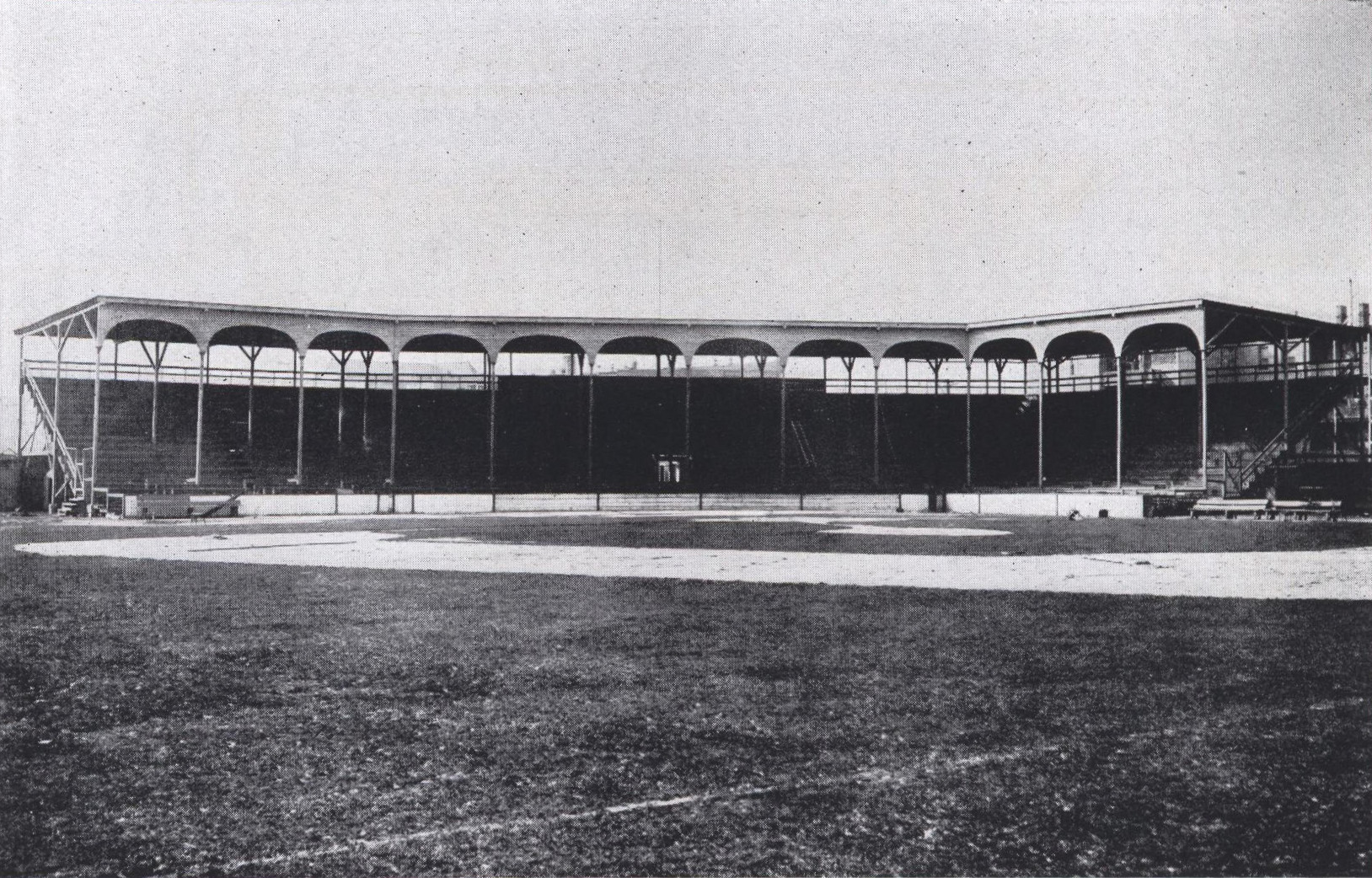

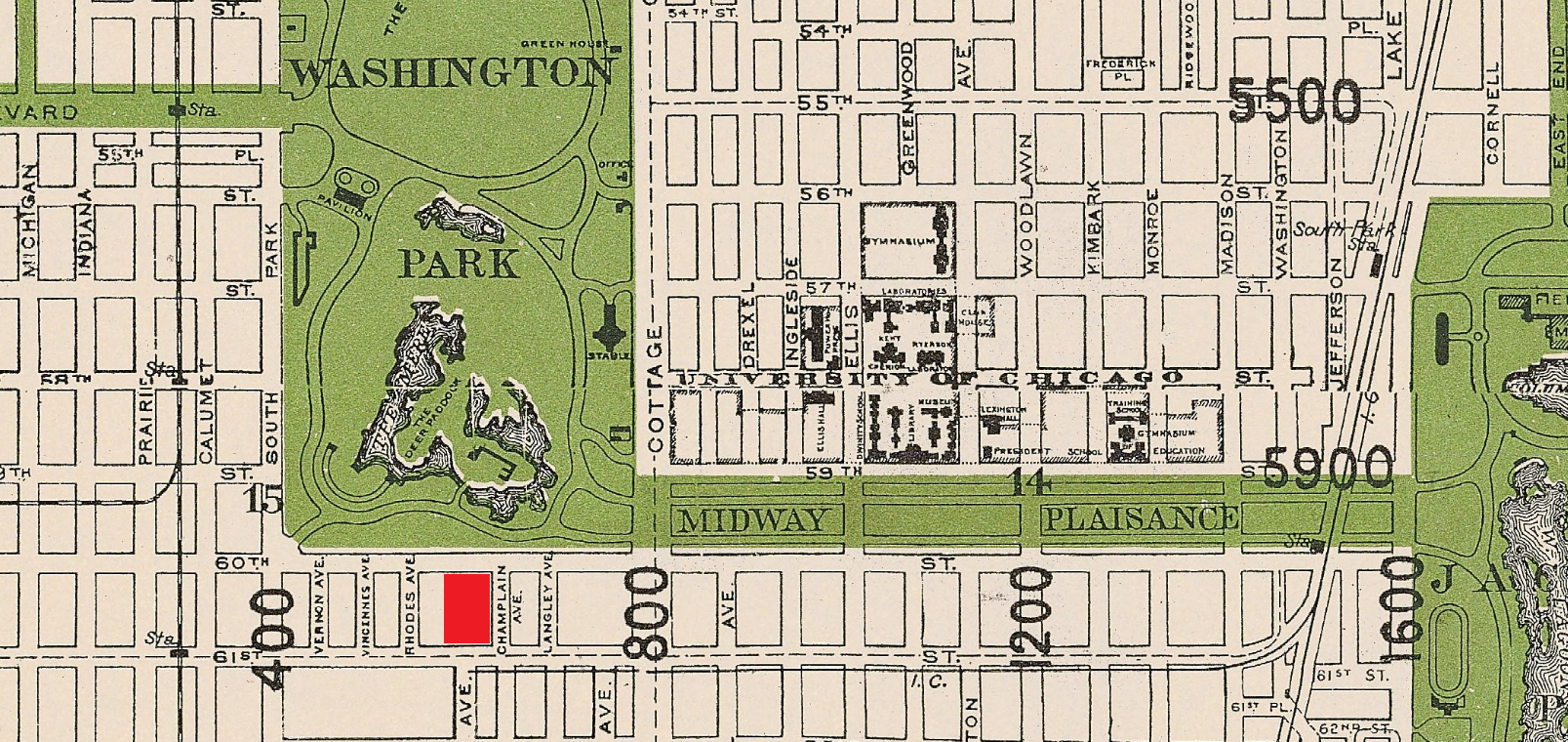

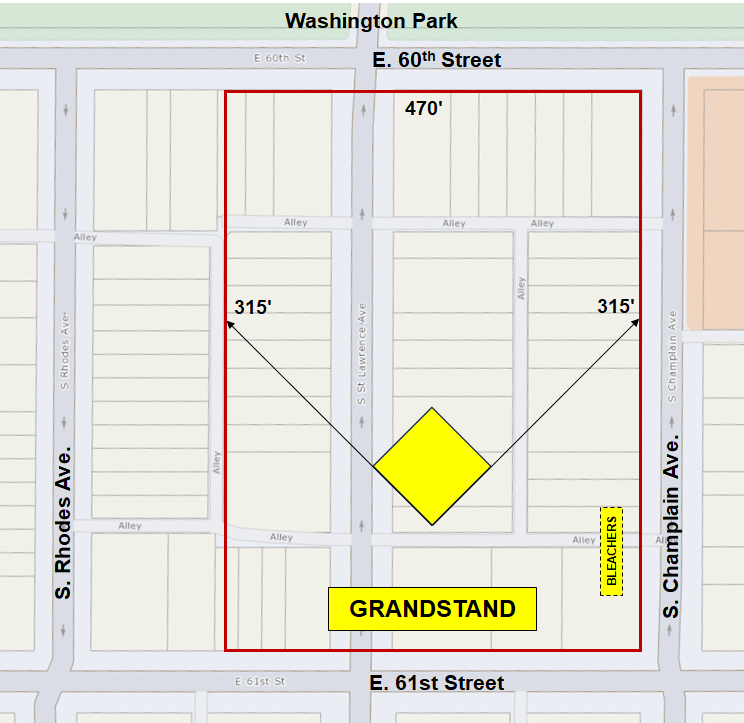

The tract Anson chose for his baseball plant was bounded on the north by 60th Street, on the south by 61st Street, on the east by Champlain Avenue, and on the west by an alley behind the houses on the east side of Rhodes Avenue.

The property that became Anson’s Park (outlined in red). Sanborn Map Company, 1895.

The property that became Anson’s Park (outlined in red). Sanborn Map Company, 1895.

During the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, the Great Eastern Hotel graced the tract’s northeast corner. The hotel was abandoned after the Exposition and burned down five years later.

Across 60th Street sprawled the greenery of Washington Park, where a flock of grazing sheep kept the lawns well-trimmed.

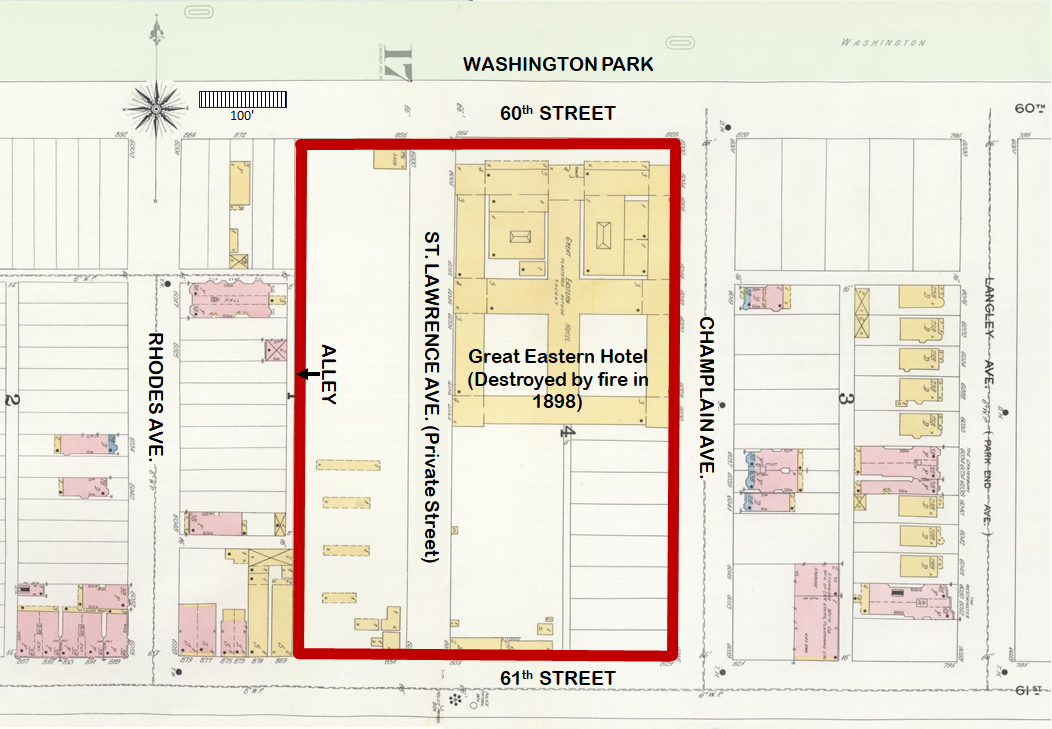

The ghost of the old Washington Park Driving Club racetrack hovered on the other side of 61st Street. The track had closed in 1905. Developers demolished the grandstand the following year and subdivided the club’s 80 acres to create a new neighborhood called the Washington Park Addition. St. Lawrence Avenue was extended north from 63rd Street to 61st.

Washington Park racetrack in its glory days. The grandstand was on the south side of 61st Street.

Washington Park racetrack in its glory days. The grandstand was on the south side of 61st Street.

Washington Park racetrack. Sanborn Map Company, 1895 (image rotated).

Washington Park racetrack. Sanborn Map Company, 1895 (image rotated).

Between 60th and 61st Streets, St. Lawrence Avenue was a street in name only. It appears on the 1895 Sanborn map as a “private street.” It did not appear on the 1910 Rand McNally Standard Map of Chicago. There may have been a wagon track across the property.

Rand McNally Standard Map of Chicago, 1910. Anson’s tract is the red rectangle south of Washington Park. St. Lawrence Avenue is the north-south street that intersects 61st south of Anson’s tract.

Rand McNally Standard Map of Chicago, 1910. Anson’s tract is the red rectangle south of Washington Park. St. Lawrence Avenue is the north-south street that intersects 61st south of Anson’s tract.

Dimensions of the tract were about 450 x 625 feet, making Anson’s proposed semi-pro park one of the largest in Chicago. Most semi-pro ballparks were around 200 x 400 feet.

The estate of Dr. A.B. MacChesney, who had died in 1903, owned the land that Anson leased. The tract already hosted an athletic field and a small set of bleachers. Hyde Park Academy’s baseball, football, soccer, and cricket squads used the field and were displaced by Anson’s arrival.

Anson planned a substantial upgrade, including a wooden grandstand “a block and a half in length,” large enough for 5,000 spectators. Construction would begin “late in the winter” of 1907, probably in late February or early March.

A group of 85 neighborhood residents, branding themselves first as the West Woodlawn Property Owners Protective Association and later as the Washington Park Improvement Association, voiced disapproval of Anson’s project. They had nothing against the national pastime, the residents said, “but didn’t want it in their own yards.” It was not an exaggeration: only a narrow alleyway separated the ball grounds from the backyards of the houses along the east side of Rhodes Avenue.

The complainants were not limited to those immediately adjacent to Anson’s ballpark. The president and vice-president of the property owners association lived on Vincennes Avenue (now Eberhart Avenue), a block-and-a-half from Anson’s tract. Association Secretary J.J. Mann lived five blocks away on Calumet.

The residents took their case to Chicago Mayor E.F. Dunne. “T.F. Hassett, 916 Sixtieth Street, wrote him several letters on the subject,” Secretary Mann told the Chicago Tribune. “We got up a big petition of property owners.”

The association initially targeted Anson’s amusement license. An amusement license was, and is, a tax on fun. The current City of Chicago website states, “A Public Place of Amusement (PPA) license is required to produce, present, or conduct any type of amusement.” Clubs, theaters, saloons, bowling alleys, pool halls, ballparks… all needed an amusement license before they could open for business.

In 1907, an amusement license required the endorsement of Chicago’s mayor, and the mayor could revoke it on a whim. It was, therefore, a convenient tool for wielding political influence. As the City Clerk working in Mayor Dunne’s administration, Anson stood to benefit from that influence.

Mayor Dunne replied to T.F. Hassett on December 17, 1906. Dunne promised not to issue Anson’s amusement license until he met with the residents and heard their grievances. But as the weeks dragged on without a resolution, the residents grew more agitated.

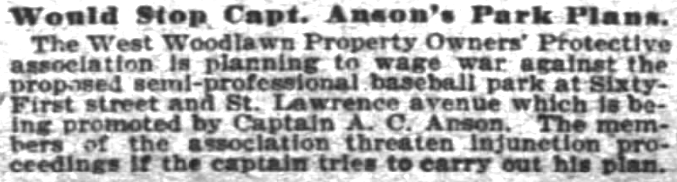

On February 17, 1907, a small paragraph buried at the bottom of page 28 in the Chicago Inter Ocean newspaper announced that the neighborhood group was “planning to wage war” against Anson and his proposed ballpark: “The members of the association threaten injunction proceedings if the captain tries to carry out his plan.”

Article announcing the community association’s plan to fight Anson’s proposed ballpark. Chicago Inter Ocean, February 17, 1907.

Article announcing the community association’s plan to fight Anson’s proposed ballpark. Chicago Inter Ocean, February 17, 1907.

The next day, February 18, Secretary Mann, accompanied by two other association members, confronted Mayor Dunne in his City Hall office.

Dunne said Mann and his friends were too late: the license had been issued two weeks before. Dunne said License Officer R.J. Hogan had conducted a secret investigation into the matter and had recommended approval of Anson’s project. Hogan was the son-in-law of a man who owned a saloon at 869 61st Street, right at the southwest corner of Anson’s ballpark.

Mann and his friends protested, saying no one they knew had seen or spoken to Hogan. According to Mann, “The mayor said probably he had worked secretly and that the people who talked to him did not know he was an officer.”

The part about Anson already having his license was a huge lie. Anson had not even made his application.

Mann and his friends exited, and Dunne hot-footed it to the City Clerk’s office. Anson wasn’t there, but Dunne left a note on his desk telling him to get the license immediately. When the property owners later checked the city records, they found that Anson’s license, complete with Dunne’s endorsement on the application, had been issued ten minutes after Mann left Dunne’s office. The license cost Anson $50.

After securing his amusement license, Anson met with his contractor to finalize the arrangements for building the wooden grandstand. Anson was racing against the property owners who threatened to take him to court. He must have thought that if his ballpark became a reality before the property owners sought an injunction, no reasonable judge would ask him to close it.

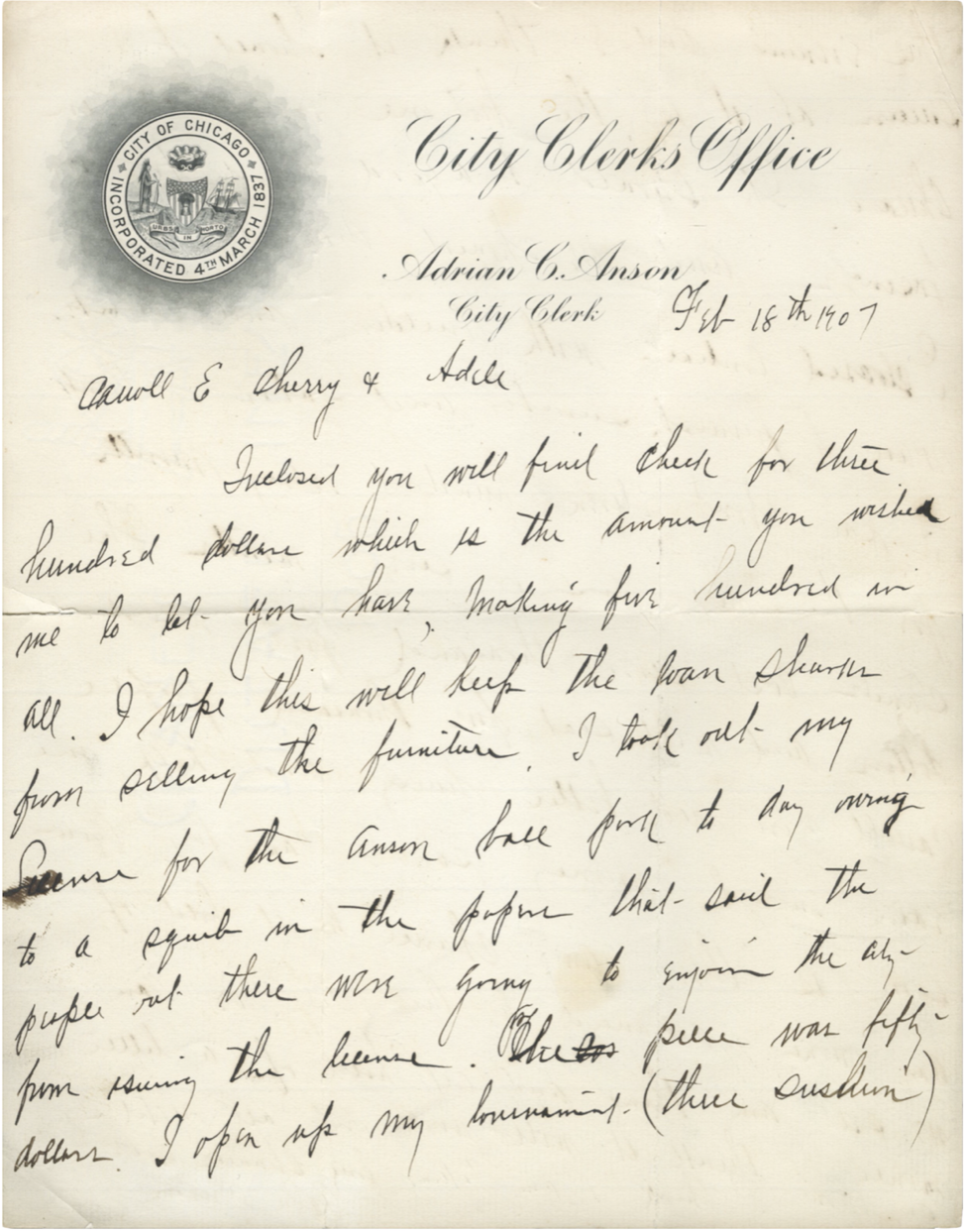

That evening, Anson penned a letter to Adele Anson Cherry, the second-born of his four daughters, and her husband, Carroll E. Cherry. Writing on the stationary of the City Clerk, with each line climbing a gentle slope from left to right, he opened with some good news. Adele and Cherry needed money, and Anson, always a loving father, was happy to help.

Inclosed you will find check for three hundred dollars which is the amount you wished me to let you have, making five hundred in all. I hope this will keep the loan sharks from selling the furniture.

He then brought Adele and Cherry up-to-date on the ballpark’s amusement license. Referring to the paragraph in the Inter Ocean that announced the neighborhood association’s displeasure, Anson indicated that he had filed for the license before the residents could stop him.

I took out my license for the Anson ball park to day owing to a squib in the paper that said the people out there were going to enjoin the city from issuing the license. The price was fifty dollars.

After discussing a billiards tournament in his pool hall, Anson returned to his grandstand.

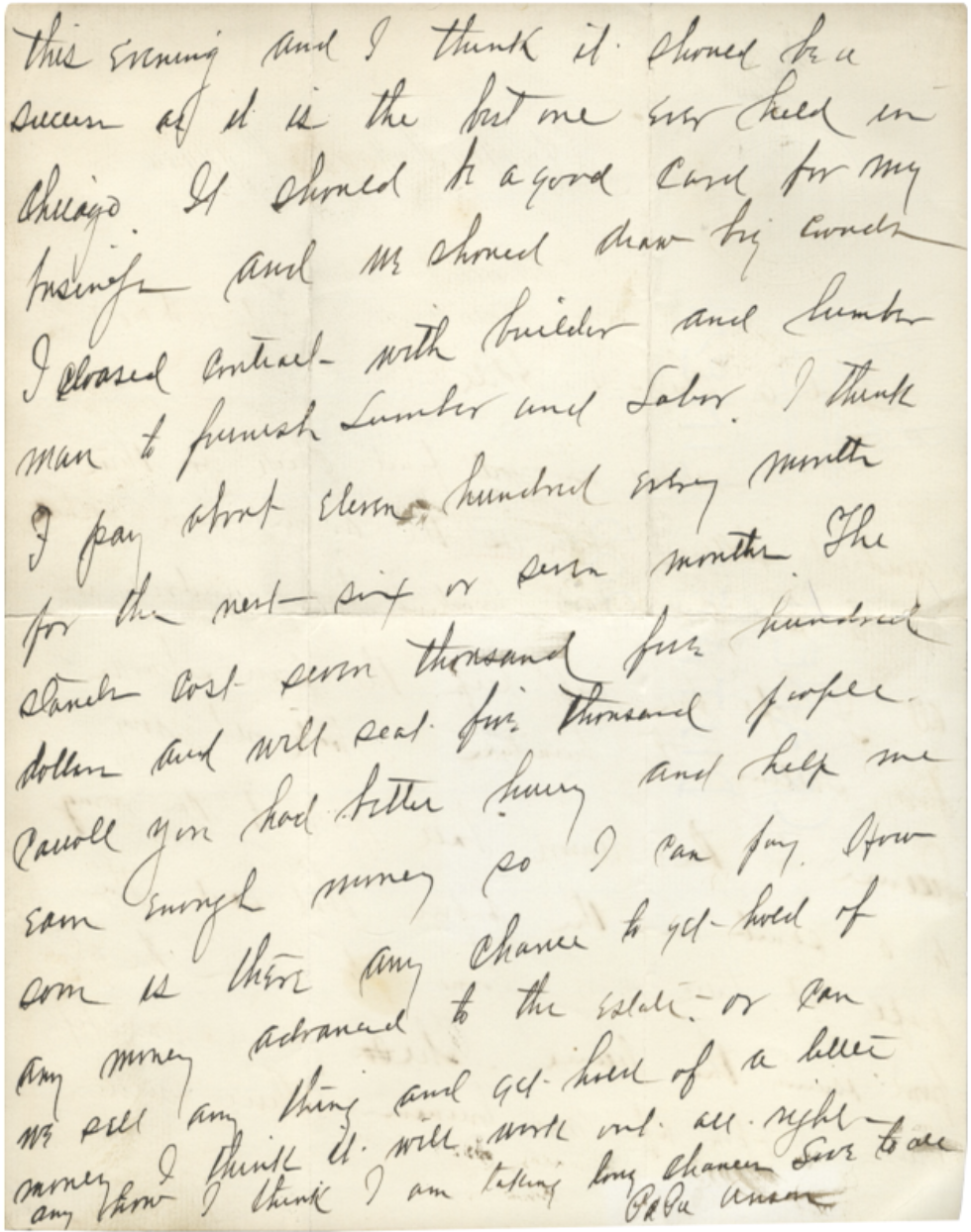

I closed contract with builder and lumber man to furnish lumber and labor. I think I pay about eleven hundred every month for the next six or seven months. The stands cost seven thousand five hundred dollars and will seat five thousand people.

It was an enormous outlay. Each monthly payment was over $35,000 in today’s money.

At the time of her engagement, the Chicago society pages described Adele as “a decided blonde.” A later witness said she was “large, blond, and affable.” Carroll Cherry was a bland-faced fellow fond of bowler hats. His brother had previously employed him in a printing company.

When Cap Anson’s father died in 1905, he left an estate worth $100,000 to Cap and his brother Sturgis. Cherry became executor of the estate. A month before Anson penned his letter, Sturgis Anson sued Cherry, alleging a dozen counts of financial malfeasance and misappropriation of funds.

With his payments to the contractor about to begin and the semi-pro baseball season not opening for several weeks, Anson had created a classic cash-flow crunch. Though Cherry was already swimming in hot water over his handling of the Anson estate, his father-in-law pressed him to finagle a few more shekels from the pile.

Carroll you had better hurry and help me earn enough money so I can pay. How soon is there any chance to get hold of any money advanced to the estate. Or can we sell anything and get hold of a little money.

Anson closed on a gambler’s note of unwarranted optimism.

I think it will work out all right. Any how I think I am taking long chances. Love to all. Papa Anson

Letter from Cap Anson to Adele and Carroll Cherry, February 18, 1907 (page 1).

Letter from Cap Anson to Adele and Carroll Cherry, February 18, 1907 (page 1).

Letter from Cap Anson to Adele and Carroll Cherry, February 18, 1907 (page 2).

Letter from Cap Anson to Adele and Carroll Cherry, February 18, 1907 (page 2).

Though he had neither a ballpark nor a team to put in it, Anson immediately challenged the Chicago White Sox to an exhibition game. White Sox owner Charles Comiskey took up the gauntlet and agreed that he and Anson would play first base for their respective teams. Anson admitted that he was not quite in playing shape. “I will have to get out and take off fifty or sixty pounds to reduce to the proper weight,” he said, “but that will be an easy matter.”

Anson’s shaky finances took a huge blow in the last week of February. He went to the Chicago Democratic Convention seeking either the City Clerk or City Treasurer nomination. He came away with nothing. No matter who won the general election, Anson would lose his $6000 annual salary when the new City Clerk took over on April 15. The “long chances” to which he had admitted in his letter to Adele and Cherry had suddenly become much longer.

Anson’s project caught another snag when the Park Owners Association rejected his membership application. The POA comprised ten park-based semi-pro teams and ten traveling teams that rotated around the circuit. The best semi-pro teams in the area belonged to the POA, and membership was imperative if Anson hoped to draw fans to his ballpark.

In 1907, the Park Owners Association was not a league in the traditional sense. Its clubs played for profit rather than for a pennant. The POA scheduled one game each week on Sunday (clubs usually scheduled an additional game each Saturday against either an independent team or another POA team), set ticket prices (25 cents for adults and 15 cents for children), and provided umpires. The association spread its ballparks throughout the city to avoid competing for the same neighborhood fan bases.

John M. Schorling opposed Anson’s application. Schorling’s Auburn Park, like Anson’s ballpark, was on Chicago’s South Side. If Anson entered the POA, Schorling desired to relocate to the northwest side near Jimmy Callahan’s Logan Square Park.

Schorling wanted Anson to approach Callahan, his friend and former teammate, and illicit a promise to support Schorling’s northern migration. Until that happened, Schorling would withhold his support of Anson’s application.

“It is up to Schorling of the Auburn Park team,” Anson said, “and he told me he would vote to admit my club if Callahan would agree to let him locate a club on the northwest side.”

Undeterred by the possibility of exclusion from the POA, Anson began to build his team. He recruited Walter Eckersall, a three-time All-America football player and a future College Football Hall of Fame member.

Eckersall had attended high school at Chicago’s Hyde Park Academy, where he played football and baseball on the same field Anson leased for his ballpark. He stayed in town for college and quarterbacked Alonzo Stagg’s University of Chicago Maroons to an unbeaten record in 1905.

The Hyde Park Academy football team in 1902, practicing on the field that later became Anson’s Park. Walter Eckersall is at quarterback, with Samuel Ransom at left halfback. The buildings in the background are probably on Rhodes Avenue.

The Hyde Park Academy football team in 1902, practicing on the field that later became Anson’s Park. Walter Eckersall is at quarterback, with Samuel Ransom at left halfback. The buildings in the background are probably on Rhodes Avenue.

Eckersall possessed exceptional speed but was not a great baseball player. Roaming left field for the University of Chicago team in 1906, he batted .250 with a .893 fielding average. Still, he was a famous athlete that people might happily pay a quarter to see. Anson planned to plant Eckersall at shortstop, front-and-center, where the fans could adore his greatness.

More substantially, Anson signed 32-year-old Louis Gertenrich as the Colt’s on-field captain. Gertenrich had previously captained the Rogers Park team. He had the reputation of being the best semi-pro player in Chicago. He broke into professional ball in 1894 when he was 19, played in the high minor leagues, and had a couple of sips of coffee in the big show: two games with Milwaukee in 1901 and a game with Pittsburgh in 1903.

The son of a successful candy maker, Gertenrich was said to be wealthy. But in 1907, he worked as a code inspector for the city and had an office in City Hall. He and Anson were probably well-acquainted.

One imagines the two former major leaguers, one sixty pounds beyond his prime, the other still trim, leaving City Hall together at noon and catching the trolley down to Anson’s Billiards on East Madison, where they enjoyed Capt. Anson’s Home Plate Buffet. And all the while talking about baseball and how much better the game was “before they put in the infield fly rule.”

Newspaper advertisement for Anson’s pool room and bowling alley, 1907.

Newspaper advertisement for Anson’s pool room and bowling alley, 1907.

With two solid hires in his pocket and little else, Anson was ready for business with or without membership in the Park Owners Association. “Despite the association’s attitude,” he told reporters, “I am going ahead and making up my team, and I guess Eckersall, Gertenrich and myself can get together a good one. I’ll have enough more crackerjacks to make all of our opponents step along some.”

Anson then dutifully pulled the requisite strings of Callahan and Schorling, and the Park Owners Association approved his membership application on March 12. The Tribune announced the news: “The veteran cap’n, who began playing ball before several of the park owners began shouting for the milk bottle, is now on equal terms as a ‘magnate’ with Jimmy Callahan, Jimmy Ryan, and the others.”

Meanwhile, the residents around Anson’s ballpark were marshaling their forces. They knew that Mayor Dunne had given them the double-cross in favor of his city clerk, who they characterized as the mayor’s “henchman.” They aired their grievances on the evening of March 16 at a meeting in Washington Park Hospital. “There was no attempt to disguise the fact that with few exceptions, the men who attended the meeting are not fond of Mayor Dunne,” the Tribune reported.

Washington Park Hospital, 60th Street and Vernon Avenue, 1909. Washington Park is on the left, on the north side of 60th. S.H. Hamilton.

Washington Park Hospital, 60th Street and Vernon Avenue, 1909. Washington Park is on the left, on the north side of 60th. S.H. Hamilton.

Anson attended the meeting but was not allowed to speak. His most vocal support came from a saloon keeper named Billy McCarthy, who owned an establishment at 61st and Cottage Grove. According to the Tribune, McCarthy “showed up as an ally of ‘The Cap,’ and, metaphorically speaking, shook his fist at the opponents of the ball park.” He was repeatedly called to order by the meeting’s chairman “and finally was declared ineligible to participate in the debate.”

The committee resolved to seek an injunction to halt construction of the grandstand. Anson saw himself as the victim. “I don’t think I have had a fair shake,” he said after the meeting. “I maintain that there hasn’t been any misrepresentation and that the ball park won’t be an injury to the people down there.” And, unable to conceal his combative nature, he added, “If they go into the courts, I will fight.”

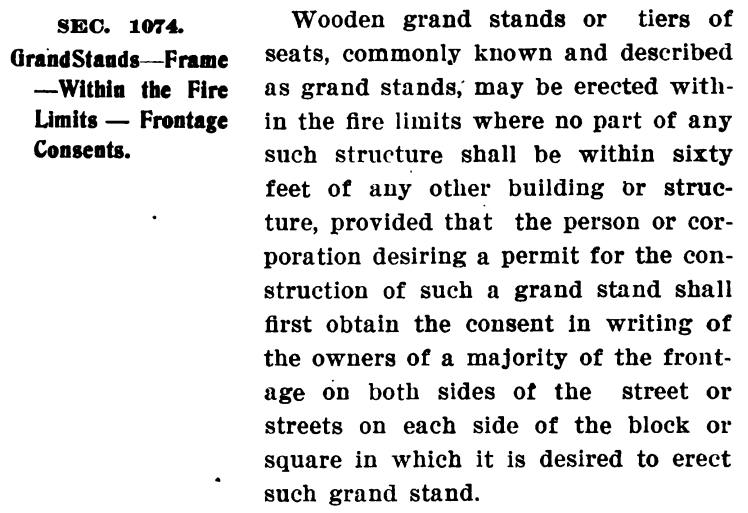

The legal combat now devolved on the arcane issue of frontage consents.

Section 1074 of the 1905 Chicago building code, entitled Grand Stands – Frame – Within the Fire Limits – Frontage Consents, stated that anyone who wished to build a wooden grandstand “shall first obtain the consent in writing of the owners of a majority of the frontage on both sides of the street or streets on each side of the block or square in which it is desired to erect such a grand stand.”

Section 1074 of Ordinance Relating to the Department of Buildings and Governing the Erection of Buildings, Etc. in the City of Chicago, Passed March 13, 1905.

Section 1074 of Ordinance Relating to the Department of Buildings and Governing the Erection of Buildings, Etc. in the City of Chicago, Passed March 13, 1905.

Approximately 2150 feet of frontage bounded Anson’s tract: 625 feet on the east side of Rhodes Avenue, 625 feet on the east side of Champlain Avenue, 450 feet on the south side of 61st Street, and 450 feet on the north side of 60th Street. To build his grandstand, Anson needed the written consent of the owners of at least 1075 feet of frontage.

Unfortunately – for Anson – he did not possess the required 1075 feet of frontage consents. According to the Tribune, when he applied for his building permit, “Anson had presented the signatures of the majority of property owners in the neighborhood.”

Anson had presented the signatures of the majority of the property owners rather than signatures representing the majority of the frontage. We do not know how much frontage Anson’s consents represented, but it must have been less than 1075 feet.

Anson’s frontage consents would have exceeded 1075 feet if he had added the 450 feet of frontage on the north side of 60th Street. His problem was that the north side of 60th Street was occupied, not by property owners who could sign on the dotted line, but by the sheep that grazed in Washington Park.

When Anson approached the commissioners who stewarded Washington Park, they said they lacked the legal authority to provide the frontage consent for his grandstand.

Ideally, Anson could have obtained over 1075 feet of consents from the property owners along Rhodes, Champlain, and 61st, whose frontage totaled 1700 feet. But there was too much local opposition to Anson, Anson’s ballpark, and the Dunne Administration.

It’s unlikely that the nameless bureaucrats who drafted Section 1074 of the building code had considered a situation in which a public park bordered a grandstand. They envisioned frontage represented by specific, identifiable property owners, and Anson had collected signatures from most of those people. Whether that was enough to satisfy Section 1074 would have to be decided in court.

With the matter unresolved and the property owners threatening an injunction, Anson turned his contractor loose to begin building the grandstand. Anson was now spending money on a project that might be illegal. He had chosen to make his “long chances,” already stretched by the loss of his City Clerk’s salary, even longer.

Before visiting the courtroom, the property owners took their beef to Building Commissioner Peter Bartzen on March 27. Bartzen was, like Anson, a Dunne loyalist with an office in City Hall. After hearing the residents out, Bartzen sent a policeman down to Anson’s construction site with orders to stop the hammering. He then kicked the can down the bureaucratic road to Assistant Corporation Counsel William Barge.

Barge reviewed the paperwork and, as reported by the Trib, “Declared that the permit had been issued legally and the property owners had not the right to revoke their consent.” Barge may not have fully grasped the issue, or he may have chosen to ignore the facts. At any rate, word went down to the South Side, and work on Anson’s grandstand resumed.

Two days later, on March 29, the Washington Park Improvement Association appeared before Cook County Circuit Court Judge Lockwood Honoré and made their case regarding Anson’s lack of frontage consents. The judge imposed a temporary injunction on further construction. A deputy sheriff brandishing the judge’s order appeared on Anson’s diamond, and the hammers and saws fell silent once more.

The residents met again on April Fools’ night. Summoning the specter of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow, they alleged that Anson’s grandstand was a “fire trap” that endangered the entire neighborhood. All present pledged to continue their fight against Anson and his ballpark.

Chicago’s citizens, living and dead, went to the polls on Tuesday, April 2, and voted early and often. Republican mayoral candidate Fred Busse defeated E.F. Dunne and the Democrats. If Anson had any political levers left at his disposal, he would have to pull them before the new administration took over. He would find few friends among the incoming Republicans.

Anson went back on the attack the Friday after the election. He demanded that the neighborhood association file a $120,000 bond to protect him from unjust losses.

The value of the indemnity Anson demanded, equal to almost $4 million today, demonstrates the money that was possible in the semi-pro game. If Anson could host 32 home games each season for three years and fill his 5000-seat grandstand with quarter-paying adults, he would rake in $120,000 before expenses. It was a wildly optimistic valuation, but even reducing the take by half left Anson with a nice profit.

Announcing the demand for indemnity, Anson’s lawyer, Herbert E. Bradley, said the residents’ fight against the grandstand “was a subterfuge to prevent the opening of a ball park.” Bradley was correct. The residents didn’t want a ballpark in their neighborhood. The attack on the wooden grandstand was just the means of execution. But their strategy had a major vulnerability: the ballpark would follow if Anson could build his grandstand.

Nothing came of Anson’s demand. “Counsel for the complainants replied that it would be an easy matter for the captain to recover if he suffered loss unjustly,” the Inter Ocean reported. The opposing counsel was wrong. Anson was slithering along the edge of a financial straight razor. He could not afford to fail. As it turned out, he could not afford to succeed, either.

Over the weekend, Anson had an unexpected visitor at City Hall. Though his inauguration was scheduled for April 15, Mayor-Elect Fred Busse showed up on Saturday afternoon, April 6, and demanded to be sworn in. Anson, as City Clerk, administered the oath. In a photograph of the ceremony, Anson dwarfs Busse – and everyone else in the room who is not standing on a chair.

Anson delivers the oath of office to mayor-elect Fred Busse. Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1907.

Anson delivers the oath of office to mayor-elect Fred Busse. Chicago Tribune, April 7, 1907.

Anson returned to Judge Honoré’s courtroom on Monday, April 8, as the neighborhood association sought a permanent injunction barring construction of the grandstand. The association added the “fire trap” issue to the “frontage consents” issue.

Association Secretary J.J. Mann took the stand and admitted that he had asked Anson for a free season pass to the chimeric ballpark. According to Mann, “He told me, ‘Yes, if you help to elect Mayor Busse.’” Given Anson’s staunch support of E.F. Dunne, Mann’s version was hardly credible.

“Mann came to me and said he might be able to help me,” Anson told the court. “He said he would be willing to if I would give him a season pass, and I told him I always take care of my friends. There wasn’t anything said about electing anybody.”

Mann then clarified his remarks: “What Anson really said to me was that if I went with him to Mayor Busse he might be able to fix me up pretty well.”

The picture that emerges is one of typical backroom politics. Mann approached Anson and elicited a minor bribe. Anson agreed that Mann could have the pass, and maybe a little more, if Mann went with him to Mayor Busse and greased the skids a bit. Mann probably lost face with the neighborhood association, but it didn’t help Anson.

After hearing more testimony on the fire trap issue, everyone agreed to have Judge Honoré decide whether the grandstand threatened the neighborhood. “I will appoint three men to go to the place and investigate and then have them report their finding to me,” he said. Honoré dispatched the Chicago Fire Marshall and a pair of insurance men to inspect the partially completed grandstand.

Anson finally caught a break on April 10. The team of experts testified that the grandstand was not a significant fire hazard and would not cause the neighborhood’s insurance rates to increase. Under the headline ANSON MAY BUILD BALL PARK, the Tribune reported that Judge Honoré had dissolved the injunction that had halted work on the grandstand.

Anson enjoyed a couple of happy days. On April 11, he attended the opening game of his old National League club, now known as the Cubs, as an honored guest. Anson presented each Cub with a gold-handled umbrella, courtesy of the Chicago Board of Trade, then threw out the first ball.

Standing at his box seat in the grandstand, Anson tossed the ball to umpire Jim Johnstone, positioned near home plate. The ball fell short, and Johnstone had to pick it up from the dirt. “Anson’s arm has clearly gone back on him,” an observer noted.

The relief provided by Judge Honoré proved fleeting. The residents’ committee returned to the office of Building Commissioner Bartzen the day after the Cubs’ opener. They again demanded that he revoke Anson’s permit, citing his lack of frontage consents. Their request confused Bartzen. “I thought this case was decided,” he told them.

Bartzen contacted Judge Honoré and learned that his ruling had resolved only the question of the grandstand being a fire trap. The issue of frontage consents remained up in the air. Bartzen revoked Anson’s permit, saying, “I do not believe a majority of the frontage consents has been obtained. The south park commissioners inform me that they have not given their consent and their consent is necessary.”

When Anson learned of Bartzen’s ruling, he was in his office, packing up in preparation for vacating City Hall. He trotted down to Bartzen’s office with Attorney Bradley in tow where, in the words of the Chicago Inter Ocean, “they found Mr. Bartzen superintending the transportation of the relics of his own power to his home.”

Herbert E. Bradley was a real estate investor who specialized in mining law. He later became a big game hunter. In 1921, Bradley took his wife and six-year-old daughter on an expedition to the Belgian Congo, where he killed five gorillas and sampled their meat. Entering Bartzen’s office, Bradley launched a too-vigorous legal attack on Bartzen’s permit revocation.

Peter Bartzen was a native of Germany who had immigrated to the New World with his family when he was ten years old. His combative nature earned him the title of “Battling Peter.” Bartzen threatened to throw Bradley into the hallway, declaring, “I would rather fight than eat.”

Anson tried to calm the waters by appealing to Bartzen’s political principles. “We’re both Democrats,” he pleaded. “Those people out there are all Republicans. Why, you couldn’t get a square meal out of them.”

“I don’t care what they are,” Bartzen shot back. “I am not granting a permit to anyone because he is a Democrat. You’ve got to comply with the ordinances to do business with me. You haven’t sufficient frontage consent, and you’ve got to get it before I’ll let you build your stand.”

Anson and Bradley exited, vowing to return to the courtroom. “I don’t want to fight it out here,” Anson told Bartzen, “for if you and I ever get into a scrap the fur will fly.”

The encounter had enlivened what the Inter Ocean alliteratively labeled “the last sad days of the dying Dunne administration.”

Anson and Bradley again visited the courtroom of Judge Lockwood Honoré. They requested an injunction to stop Bartzen from interfering in the construction of the grandstand. Judge Honoré refused to enjoin the order, declaring that Anson lacked any standing in his court.

The formal inauguration of the Busse Administration took place on Monday evening, April 15, and a new ensemble of Republican bureaucrats invaded City Hall on Tuesday. With admirable persistence, Anson appeared in the building commissioner’s office that morning and filed for a new permit.

Joseph Downey, an ardent Cubs fan and a good friend of Cubs owner Charles Murphy, had replaced Peter Batzen. Anson probably thought that his status as the greatest player in the history of Chicago baseball would give him an in with the new commissioner.

Like his predecessor Bartzen, Downey kicked the can to the corporation counsel’s office. Corporation Counsel Edward J. Brundage came back with the opinion that Anson lacked the necessary frontage consents. Downey turned down Anson’s application.

The captain was in a squeeze play. His city salary had evaporated. He was already making payments to his contractor. Chicago’s semi-pro season opener was four days away. All Anson had to show for his financial and legal efforts was an unusable, unfinished wooden grandstand.

Anson found a brave, revolutionary, and very expensive solution: tear down the wooden grandstand and replace it with a steel grandstand.

Section 1074 of the building code specifically addressed wooden grandstands. The code said nothing about steel grandstands because no one in Chicago had ever wanted to build one.

All of Chicago’s semi-pro teams played in front of wooden grandstands. The Cubs’ West Side Park and the White Stockings’ South Side Park deployed wooden grandstands. The major leagues’ first concrete-and-steel ballpark, Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, would not open until 1909.

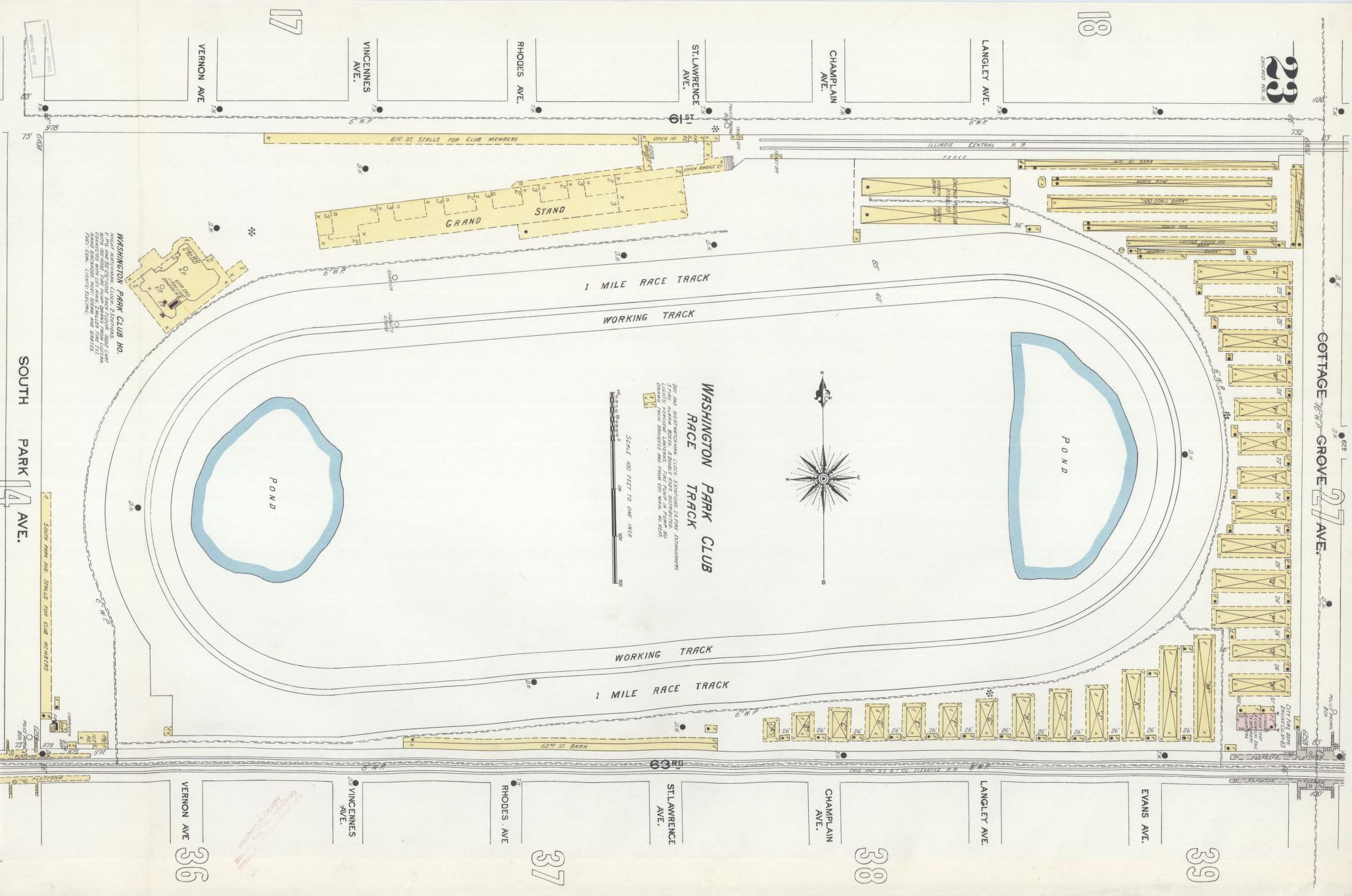

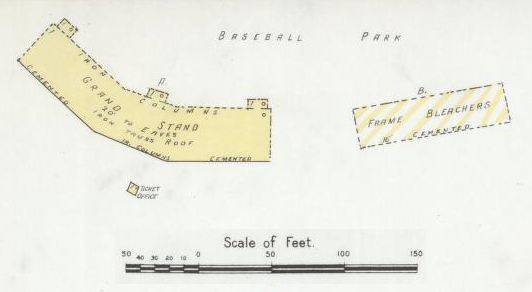

Though steel grandstands were rare, Anson had access to a fine example 36 miles away at Dellwood Park, located just north of Joliet in Lockport.

The ballpark was almost brand-new. It had opened for business on June 3, 1906, with a game between Joliet’s semi-pro team and the Legion Giants, a Black team from Danville. The Joliet Herald News reported that the grandstand held “about 1,800 people.”

The grandstand was said to be steel, but it was probably iron. During a pause in construction, the Herald News reported that the builders were awaiting a shipment of “structural iron.” The 1909 Sanborn fire insurance map shows an “iron truss roof” supported by cemented “iron columns.” A section of bleachers flanked the covered grandstand.

Dellwood Park grandstand and bleachers. The grandstand was about 180 feet long and 40 feet deep. North is to the left. Sanborn Map Company, 1909.

Dellwood Park grandstand and bleachers. The grandstand was about 180 feet long and 40 feet deep. North is to the left. Sanborn Map Company, 1909.

Anson had to move fast. He turned up in Joliet on Wednesday, April 17, the day after Building Commissioner Downey turned down his application for a new permit. The Herald News reported Anson’s arrival under the headline, “CAP” ANSON VISITS JOLIET. “The veteran baseball player came to look over the grandstand at Dellwood Park,” the newspaper told its readers. “He intends to model the one he will put up on the south side in Chicago after the local one.”

While Cap Anson tried to build his ballpark, Lou Gertenrich assembled the team that would play in it. Anson dubbed his team “Anson’s Colts,” a throwback to the captain’s days as a major league manager of young men.

The roster included three former Rogers Park players: center fielder Gertenrich, left fielder Henry Butcher, and third baseman Hugh Cook. Two players had been with the semi-pro Streator Reds: catcher Mike Sampson and second baseman Walter Rooney.

The team harbored a fair number of college men. Eckersall, Rooney, and pitcher Jimmy Sullivan had played baseball at the University of Chicago. Sullivan’s senior quote in the University of Chicago’s 1907 yearbook: “Not related to John L., but I can lick any guy in Cook County.”

Cook had captained the Purdue baseball team. First baseman Al Weinberger had starred with Northwestern on the damond and the basketball court.

Rooney was completing a law degree and would later become a Cook County Assistant District Attorney. Cook had a degree in mechanical engineering and designed machines for a tractor factory in Kewanna, Indiana. Playing for the Colts was purely a side gig.

Butcher was the only Colt destined to make the majors. He would play 64 games with Cleveland spread over the 1911 and 1912 seasons.

Other Colts included pitchers Jimmy Clark, Jack Houston, and Billy Wayland. Their provenance is unknown.

The Colts played their first game on Saturday, April 20, as the visiting team in Rogers Park. Anson’s team lost 3-4.

Walter Eckersall had been advertised as the Colts’ shortstop. But when the Colts took the field, the gap between second and third was filled by Jack Corbett, a 19-year-old phenom from the sticks of Indiana. Eckersall, who was probably still in school at the University of Chicago, would not enter the lineup until mid-June.

Before committing to the expensive steel structure, Anson made two desperate moves to salvage the in-progress wooden grandstand. On the Monday following the Colts’ first game, Anson and Bradley appeared before the park commissioners and pleaded for their frontage consent. The commissioners chose to remain neutral, dooming Anson to defeat.

The next day, Anson was back in Judge Honoré’s courtroom seeking an injunction to prevent the city and Commissioner Downey from forcing him to stop work on the wooden grandstand. He maintained that, back in February, then-Commissioner Bartzen had granted the permit and, once granted, the city had no right to revoke it.

The argument failed to sway the court. “I’m sorry that I cannot assist in this laudable enterprise,” Judge Honoré ruled, “but the law on the subject seems clear.”

“I will erect my park at any cost,” Anson said defiantly. “It will cost me $10,000 more to have steel stands, but I will have them built.”

Anson had already spent $2500 on the wooden grandstand. Replacing it with the steel grandstand would cost $10,000 more. The cost of his project had ballooned from $7500 to $12,500 without a completion date in sight.

At this point, the captain could have admitted defeat, released his players, sold the lumber for scrap, taken the loss and walked away. Anson would be humiliated but not broken. Yet he persisted, heroically, foolishly, or both, like the blackjack player who remains at the table trying to play his way out of a hole only to descend deeper into debt. He was going to by God build this ballpark if it took every penny he had.

Anson’s Park hosted its first game on Sunday, April 28. The day before, Officer Reaty of the Woodlawn police station was walking his afternoon beat in cool 50-degree weather when he heard hammering inside Anson’s fence. He investigated and found Anson supervising the construction of temporary bleachers.

Officer Reaty asked to see Anson’s construction permit and learned that Anson had not obtained one. Anson hopped on a trolley to City Hall – open on Saturdays back then –and returned to the South Side bearing the permit.

Anson’s Colts took the field in their home park wearing light gray uniforms with Anson emblazoned across the front in Old English script. The jerseys had dark trim on the sleeves and collars. A white belt held up the pants. Behind pitcher Jimmy Clark, the Colts defeated Kankakee 4-2.

The Tribune summarized the game in its Monday edition with a single paragraph: “Anson’s new ball park at Sixty-first Street and Champlain Avenue, which has been ‘at bat’ in the courts on several occasions, was opened to the public yesterday. The crowd was small. Anson’s Colts put up a good game and handily defeated the Kankakee Browns.”

The small crowd was a portent of future troubles. Anson possessed an overblown belief in the power of his name. He thought a team called Anson’s Colts, owned by Cap Anson, playing in Anson’s Park, wearing jerseys with Anson across the front, would induce Chicago’s citizens to fill his pockets with quarters. But the quarters departing Anson’s pockets exceeded the quarters coming in.

Anson’s legal struggles, reliably reported in the Tribune and Inter Ocean, did not help his attendance. He came across as a poor businessman who chose a contentious site for his ballpark, failed to obtain a legal permit, and tried to extricate himself from the problem by bullying his neighbors. The neighborhood support that semi-pro teams relied on did not exist, and the Colts, a solid but unspectacular squad, were not good enough to pull in fans from around the city.

Anson might have drawn a few more fans by donning a uniform and taking the field himself, but in early 1907, he had not yet reached that level of desperation. He attended games wearing a suit appropriate for a park magnate while Gertenrich handled the on-field maneuvers.

The captain continued to shove his Sisyphean semi-pro park up the political hill, only to have it roll back down. As he should have expected, Republican Mayor Fred Busse revoked his amusement license, and Anson’s Park hosted no games on the first weekend of May.

The Tribune’s Hugh Keogh, writing under his usual pseudonym of HEK., expressed his dismay: “The fact that the respected and venerable Cap Anson cannot open his ball park is received with semi-profound astonishment (Help).”

The former City Clerk put aside any animosity he may have harbored for the new Republican administration and gave Mayor Busse a personal tour of Anson’s Park. He described the “fireproof grandstand” that would someday replace the temporary bleachers, and no doubt regaled the portly little Busse, already suffering from the heart disease that would kill him seven years later, with tales of pennants won and lost.

Dutifully impressed, Busse promised that Anson would receive his license and that the city would not interfere with the upcoming weekend’s games. Anson had finally cleared the legal and political hurdles that blocked his path.

“Capt. Anson was entertaining all friends who happened to be in his way last night,” the Trib reported on Saturday, May 11, “for all the trouble about his ball park was ended. Mayor Busse issued orders that the games scheduled for Anson’s park today and tomorrow be not interfered with and that an amusement license be issued.”

For the first time, on May 11 and 12, Anson’s Park hosted two games in a single weekend. Still seated on temporary bleachers, the spectators watched the Colts lose to the Oak Leas 4-9 on Saturday but defeat the Marquettes 7-4 on Sunday.

The Colts ended the month with a mediocre record of four wins and five losses.

Anson finalized the contract for his steel grandstand on June 5. The new structure would seat 2000 fans, less than half of what he had originally planned. Anson hoped to complete his ballpark before the Fourth of July crowds arrived.

Economic necessity had softened Anson’s stance against playing non-white opponents. The Black and Cuban teams were great draws, always bringing fans of quality baseball to the parks. At this point in his life, Anson valued money more than principle.

On Saturday, June 8, Anson’s Park hosted the All Havanas, who defeated the Colts 7-5 in 12 innings. One week later, the Leland Giants visited Anson’s Park. Rube Foster, the Giants’ star pitcher, was confined to right field, and the Colts won 6-2.

The June 15 game against the Giants marked the first appearance of Walter Eckersall in a Colts uniform. Anson had originally planned to plant his star attraction at shortstop. But when the game commenced, Jack Corbett still stood at short. Eckersall was a lonely figure in right field, the position reserved for the worst fielder. “Eckie” played well, rapping a double and scoring two runs. The box score did not record stolen bases, but the Trib reported that “Eckersall distinguished himself by his sensational base stealing.”

After beating the Leland Giants, Anson applied to the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues for protection under the National Agreement. The most salient feature of the Agreement, signed in 1903, was the right of reservation: a player was perpetually bound to the club that owned his contract. Joining the National Agreement would protect Anson’s roster from poaching by major and minor league teams.

“Cap is a firm believer in the theory that his team can wallop anything from the world’s champion White Sox and the Cubs, through the American Association, Three I League, Gulf States, and P.O.M. leagues, and that for this reason his team should be taken in and receive the same protection as those that he is confident he can beat,” the Inter Ocean explained.

It was a ridiculous request, obviously made for publicity purposes. The National Agreement existed between leagues, not individual teams. And the Colts’ middling semi-pro record, 7-6 after the Giants game, hardly put them on the same footing with the professional teams.

Cap Anson was, independent of his faults, a good baseball man. Someone once said, “Anson could take nine cigar signs and win the pennant.”

Given appropriate funding, he could have assembled and managed an excellent team comprising the best talent in the Midwest. There were no salary limits or reserve clauses in semi-pro ball; players took the field for whoever gave them the most money. But Anson could not pay the salaries required to attract a top-flight team.

Colts third baseman Hugh Cook earned $15 weekly for playing two games, a fact revealed to the world by his hometown newspaper. It wasn’t a great deal of money. A union hod carrier in Chicago made $16.80 each week. A Class D minor leaguer made about $25 a week.

Anson’s Colts swam in the same talent pool from which Jimmy Callahan, Jimmy Ryan, and the other park magnates slaked their thirst. As a result, Anson’s Colts were not much better or worse than the other semi-pro teams. The Colts of 1907 were not the sensational collection of “crackerjacks” that Anson needed to draw the big crowds.

Early in the 1907 season, Anson herded his Colts into the studio of George R. Lawrence for a team photo. One hundred ten years later, Christie’s auctioned off a 13×10.75-inch print of the photograph for $500.

Christie’s incorrectly identified the picture as “the 1908 Anson Colts.” But the presence in the photo of first baseman Al Weinberger indicates that the photo was taken before June 30, 1907, when Weinberger made his final appearance with the Colts. Other players in the photo, such as shortstop Jack Corbett, were long gone by 1908.

Anson’s Colts early in the 1907 season. Front row (left to right): Clark, Wayland, Sampson, Corbett. Middle row: Cook, Eckersall, Cherry, Rooney, Butcher. Back row: Sullivan, Houston, Anson, Weinberger, Gertenrich. George R. Lawrence & Co.

Anson’s Colts early in the 1907 season. Front row (left to right): Clark, Wayland, Sampson, Corbett. Middle row: Cook, Eckersall, Cherry, Rooney, Butcher. Back row: Sullivan, Houston, Anson, Weinberger, Gertenrich. George R. Lawrence & Co.

Anson, 55 years old, stands in the back, towering over his players. Al Weinberger, 22 years old, stands to the right of Anson. Weinberger had played center for the Northwestern basketball team. On his WWII draft registration, he recorded his height as six-foot-three. A bowler hat conceals the top of Anson’s head, but his shoulders are clearly above Weinberger’s. If Weinberger was six-foot-three, then Anson must have been at least six-foot-four, possibly six-foot-five.

Center fielder Louis Gertenrich, at the far right of the back row, is diminutive compared to Anson.

Carroll Cherry sits before his father-in-law appearing vacuous and out of place. Walter Eckersall, to the left of Cherry, shrinks beneath the weight of the massive Ansonian fist that rests on his shoulder.

Anson attended a Press Club banquet honoring Charles Comiskey on Monday evening, June 24. His new grandstand was nearing completion, and Anson must have been in a good mood. Tribune writer Charles Dryden, said to be the most highly paid baseball writer in the country, wrote, “Capt. Anson came in late, but being a sure two-handed eater the grand old man soon caught up with the field.”

Anson’s steel grandstand finally saw the seats of paying customers on Saturday, June 29. “Cap Anson’s new steel grand stand will be used this afternoon for the first time at the game between Anson’s Colts and the Oak Leas,” the Trib advertised.

The fans who turned out saw Anson’s Colts defeat the Oak Leas 11-3. The Tribune reported the results under the headline ECKERSALL STARS FOR ANSON. Ex-Maroon’s Base Running Feature of Game with Oak Leas, Won by Colts. The story and box score did not include details of Eckersall’s exploits.

A recently reworked diamond contributed to seven errors by the Oak Leas. “Frequent errors because of the new field made it easy for the home team,” the article noted.

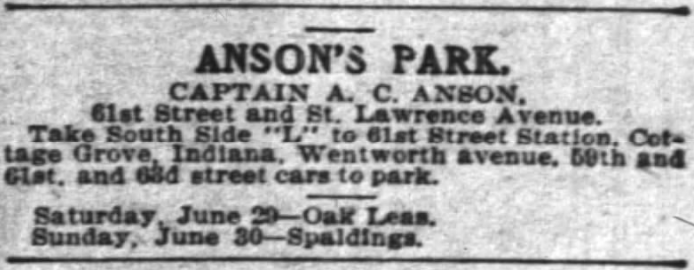

Anson’s good fortune carried into Sunday as his Colts defeated the Spaldings, giving the team an 11-7 record.

Notice in the Chicago Inter Ocean, June 30, 1907, advertising the weekend’s games at Anson’s Park with directions for taking the train or streetcars to the park.

Notice in the Chicago Inter Ocean, June 30, 1907, advertising the weekend’s games at Anson’s Park with directions for taking the train or streetcars to the park.

Anson’s Colts celebrated the Fourth of July, which fell on a Wednesday, with a split doubleheader against Jimmy Callahan’s Logan Squares. The teams played the morning game in Logan Square Park, with the Colts losing 5-6. Taking exception to a call, Anson came onto the field and gave the crowd a master’s class in kicking. Umpire Conley, unintimidated by the great captain, tossed Anson from the park.

The players then boarded the southbound cars for Anson’s Park to complete the bottom half of the twin bill. The afternoon game featured Jimmy Callahan himself on the mound. The former major leaguer, 33 years old, earned a ten-inning, 2-1 complete-game victory.

The semi-pro teams did not belong to a proper league and had no official standings, but the Joliet Herald News attempted an informal “power ranking” after the July 21 games. The Normals were deemed the best club, with a record of 21-9. Next came the West Ends (18-8), Leland Giants (17-8), Jimmy Callahan’s Logan Squares (“an even record throughout the year”), Gunthers (23-13), Jimmy Ryan’s Lawndales (17-9), and the South Chicagos (13-8).

Anson’s Colts were far down the list at eighth. The Herald News credited the Colts as having “broken even in twenty-six games.” The results published in the newspapers each Sunday and Monday morning indicate a record of 14 wins against 12 losses. At best, the Colts were an average semi-pro team, a long toss from the crack outfit, ready to take on the Cubs and White Sox, that Anson advertised.

The semi-pro season was half-gone, but Anson’s Park remained unfinished. Although the grandstand was in use, a large crew of workmen remained in the park, including 40 union men – carpenters, electricians, and general laborers – and 17 non-union painters.

A committee representing the Associated Building Trades confronted Anson on July 22 and protested the presence of the non-union painters but, as reported by the Tribune, “failed to get satisfaction.” The union placed Anson on the “unfair” list and threatened him with a general strike. The union workmen were happy to put down their tools if the non-union painters remained.

Anson capitulated immediately. “The difficulties were settled at once by Captain Anson issuing an order to exclude all mechanics not members of the union in which trade they were working,” the Inter Ocean reported.

Anson’s Park had its Grand Opening on Saturday, July 27, 1907. To celebrate, Capt. Anson squeezed into a Colts uniform and took the field as the third base coach. The Tribune reported that it was Anson’s first appearance in a uniform since 1897.

The day was sunny and pleasant, with a high temperature of 72 degrees. The completed grandstand was three months late, half as large as originally planned, and thousands of dollars over budget. But, as Anson stood in the sun and surveyed his ballpark, he must have been proud. He had created – finally – Chicago’s newest and nicest semi-pro baseball park. And with a grandstand constructed of iron and steel, it should have been the city’s most permanent park.

At some point in the 1908 season, an anonymous photographer for the Chicago Daily News attended a game in Anson’s Park and captured a remarkable series of images. By that time, Anson was appearing in the games regularly. The pictures show us what Anson saw on the day of his park’s Grand Opening. They also allow us to describe Anson’s Park in some detail.

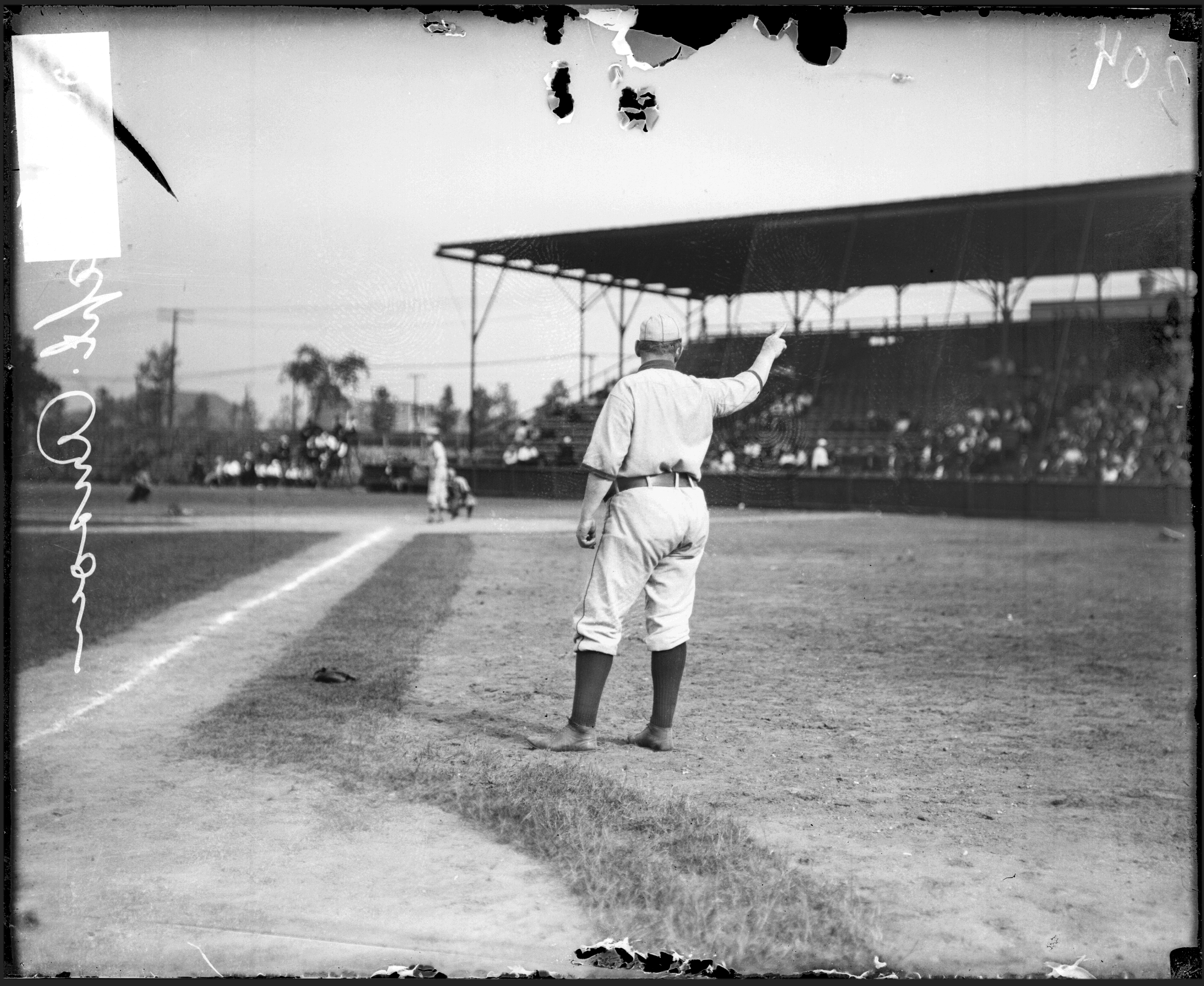

Capt. Anson coaching third base in Anson’s Park. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Capt. Anson coaching third base in Anson’s Park. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

The park’s main entrance was at the corner of Champlain and 61st. The grandstand paralleled 61st Street and was probably centered between Champlain Avenue and the alley east of Rhodes Avenue.

The grandstand had about 20 rows of seats, making it roughly 45 feet in depth. The length is more difficult to estimate since none of the images captured the grandstand in its entirety. But it was probably about 220 feet from end to end, making it similar in size to the grandstands at Dellwood Park and Gunther Park.

Capt. Anson coaching third base in Anson’s Park. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Capt. Anson coaching third base in Anson’s Park. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Fans who sat beneath the grandstand’s massive roof enjoyed theater seats with backs. The seats behind home plate were protected by a screen stretched between the roof and the low fence at the base of the grandstand.

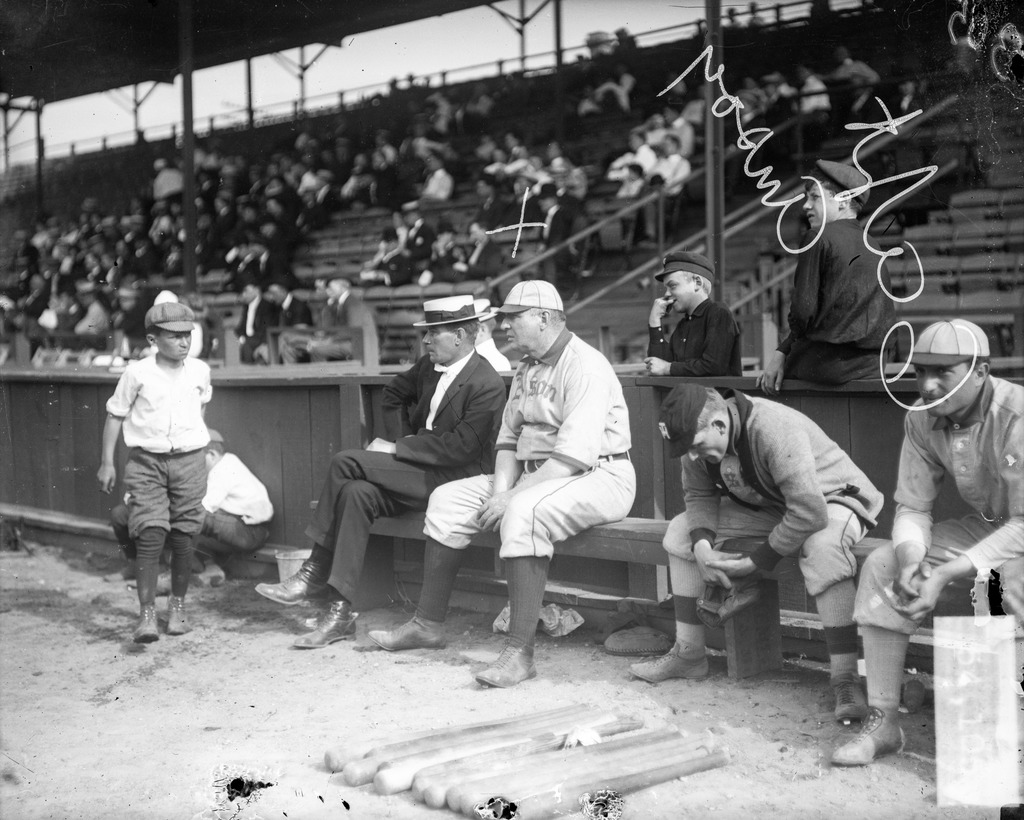

Anson sits beside Carroll Cherry with the grandstand behind them. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Anson sits beside Carroll Cherry with the grandstand behind them. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

A section of uncovered seats without backs flanked each end of the grandstand. They may have been reserved for Black spectators. A set of bleachers, with the south end near 61st Street, paralleled Champlain Avenue.

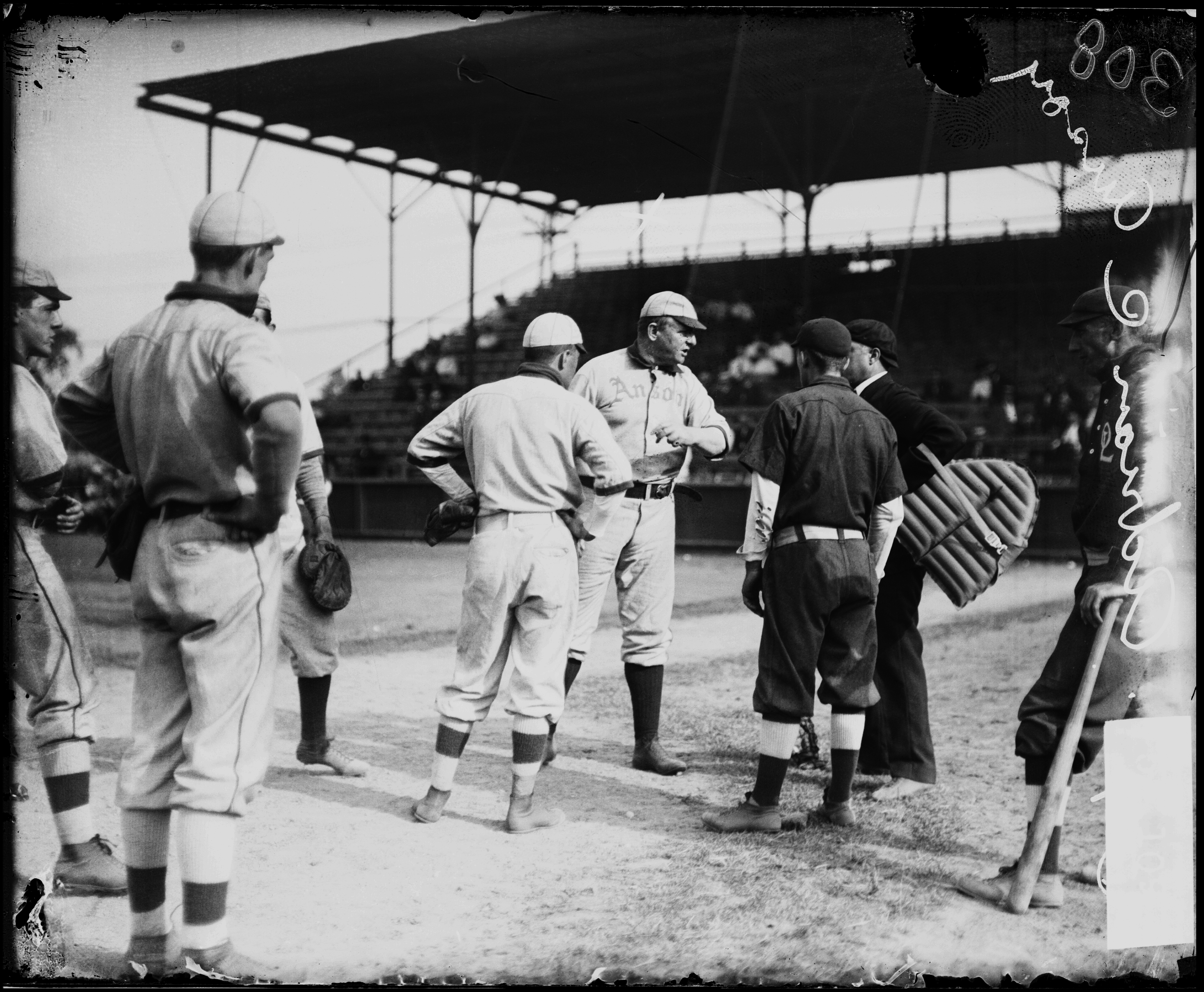

Anson warming up before a game in Anson’s Park. The buildings in the background are at the corner of 61st and Rhodes. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Anson warming up before a game in Anson’s Park. The buildings in the background are at the corner of 61st and Rhodes. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

If the outfield fence ran near the edge of the property, then Anson’s Park possessed major league dimensions: 315 feet down the foul lines and 470 feet to straightaway center. Massive expanses of foul territory occupied each side of the diamond.

The King of Kickers arguing with an umpire during a game in Anson’s Park. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

The King of Kickers arguing with an umpire during a game in Anson’s Park. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

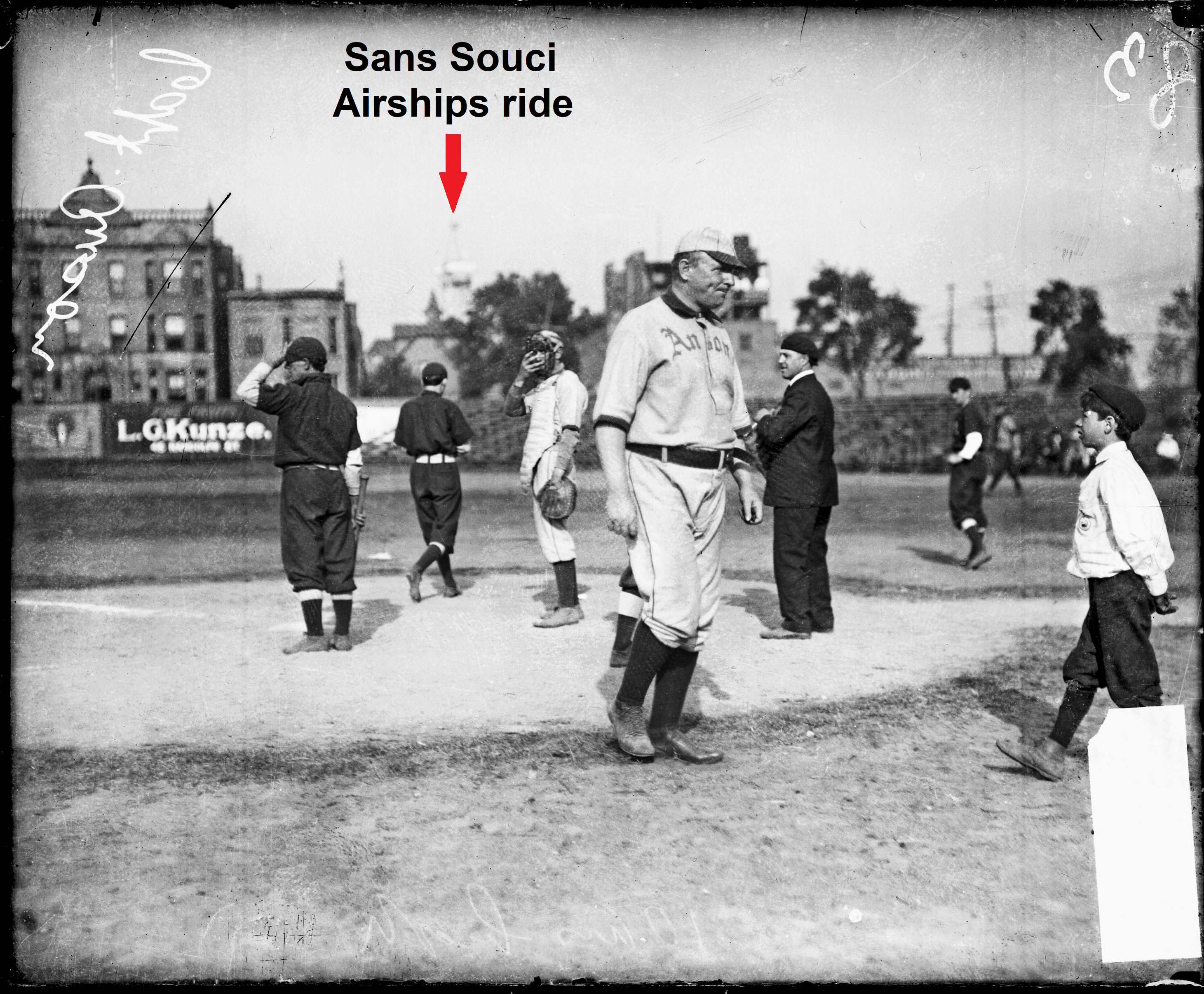

A right-handed batter who stood at home plate and looked straight ahead towards Champlain Avenue saw the metal tower of the Airships ride at Sans Souci Park. The tower’s location relative to Anson’s Park is a key to understanding the positions of the grandstand and playing field.

Looking east across home plate. The Airships ride at Sans Souci Park is in the distance. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Looking east across home plate. The Airships ride at Sans Souci Park is in the distance. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Airships ride at Sans Souci Amusement Park.

Airships ride at Sans Souci Amusement Park.

The amusement park’s entrance was at the corner of 60th and Cottage Grove. The Airships ride was farther south down Cottage Grove, closer to 61st Street, as shown in a photograph taken near the entrance.

Entrance to Sans Souci Park at Cottage Grove and 60th, looking south down Cottage Grove. The Airships tower is to the left of the buildings. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

Entrance to Sans Souci Park at Cottage Grove and 60th, looking south down Cottage Grove. The Airships tower is to the left of the buildings. Chicago Daily News, 1908.

If the Airships tower was around 6044 Cottage Grove, and the home plate at Anson’s Park was more-or-less due west of the tower, then the plate would have been about 160 feet north of 61st Street. In 1907, baseball’s rules called for the grandstand to be 90 feet behind home plate (though in the 1908 photographs of Anson’s Park, the distance appears to be less).

Anson’s Park shown on a modern map from the City of Chicago interactive mapping website. The size and location of the park’s features are approximations.

Anson’s Park shown on a modern map from the City of Chicago interactive mapping website. The size and location of the park’s features are approximations.

The 1908 photographs capture the grandstand’s most salient feature: a lack of spectators. Most seats are empty.

With Anson in the coach’s box for the Grand Opening game, the Colts defeated the Artesians 8-7. The Colts were on a roll. Between July 14 and August 11, they won eight out of ten games, ending the streak with a 19-13 record. But their fortunes immediately reversed, and they lost seven of their next nine games.

Rube Foster and the Leland Giants appeared in Anson’s Park on Saturday, August 24. Foster was a future Hall of Fame pitcher who could have starred in the majors if given a chance. He mowed down the Colts, giving up one run on three hits, striking out five, and walking one as the Giants took a 7-1 win. His treatment of the Colts showed the gulf that divided Anson’s team from the real professionals.

A few days later, Anson sent the City of Chicago a bill for $2505.85. The precisely tabulated sum was the money Anson had spent building his wooden grandstand before Battling Peter Bartzen revoked his permit. Anson contended that he began constructing the wooden grandstand in good faith after receiving his permit from the city. Whatever money he sank into the wooden grandstand, then, should be reimbursed by the city.

Corporation Counsel Brundage refused to pay the invoice. But Building Commissioner Downey graciously consented to refund the $26 that Anson had paid for the original permit to build the wooden grandstand.

The request for reimbursement had no chance of success. Anson’s motive must have been to cause someone at City Hall a few fleeting moments of consternation. But it may have reflected how desperate Anson was for money. The new steel grandstand had sucked away all of his capital, and he was already circling the financial drain.

On Sunday, September 15, the Colts boarded the train for Streator, 78 miles southwest of Chicago, for a game against the Streator Reds. Whatever hype machine Anson possessed had been working overtime. “Anson’s Colts are undoubtedly the biggest baseball card of the year,” the Streator Times told its readers, “and you’ll have to be there early to get a seat.”

The reporter proved that public perception may differ wildly from reality: “Anson is now rich enough to have both the hay fever and the gout and is in base ball only because he likes it.” The truth was that Anson was nearly broke. He was “in base ball” to make money, but baseball was driving him to bankruptcy.

Anson’s name carried weight in the sticks of Streator, and he commanded stiff terms for the appearance of his mediocre team. The year’s largest crowd filled the bleachers and saw the Colts win 6-1, but the bodies did not translate to dollars for the game’s promoters. “With the guarantee necessarily given to secure Anson’s team,” the Times complained on Monday morning, “the management didn’t make any big money yesterday.”

The baseball season was winding down. The National League completed its schedule on October 6, with the Chicago Cubs possessing the pennant. By October 12, they were world champions after downing the Detroit Tigers in five games. The first game ended in a 3-3 tie due to darkness; the Cubs swept the next four.

Anson’s Colts played their last game of the 1907 season on October 20 in Joliet’s Dellwood Park, in a game to benefit Harry Kane, a near-destitute semi-pro pitcher suffering from typhoid. A biting wind and temperatures in the low 50s greeted the players. Dellwood Park’s steel grandstand, the model for Anson’s personal money sink, hosted 800 brave fans. The Colts eked out a 9-7 win to end their season with a record of 25-21-1.

Capt. Adrian C. Anson, possibly in 1907. Bain News Service.

Capt. Adrian C. Anson, possibly in 1907. Bain News Service.

Cap Anson soldiered on after the 1907 season, trying to milk some revenue from his team and ballpark. In 1908, he took to the diamond regularly. On some days, he would bend his 56-year-old knees and hunker his massive frame into a catcher’s crouch. After one game, a reporter labeled Anson “poor old Cap.”

Anson had built an excellent baseball park, but the effort ruined his finances. By June of 1908, he could no longer pay his players’ salaries. He told the Colts they would receive a share of the gate receipts but not a regular paycheck. Gertenrich, Cook, and three other players immediately walked out.

Anson was busted, with debts totaling $20,000 against assets of less than $8000. He owed $6500 in unpaid rent on the Madison Street building that hosted his bowling alley and pool hall, $3900 to the Brunswick-Blake-Collender company that manufactured billiards and bowling equipment, $2649 to the Blatz Brewery, and $1306 to the Grommes and Ullrich whiskey company.

The Streator Free Press included Anson’s Colts among the captain’s bad investments: “The team, it is said, has been anything but a paying investment, and this venture is partly blamed for the financial difficulties of the ‘Cap.’”

Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the future Commissioner of Baseball, stewarded the division of Anson’s properties. The captain’s greatest asset was his name, but he couldn’t convert his name into dinero. During Anson’s bankruptcy proceedings, the Trib’s Hugh Keogh wrote, “Chicago is the poorest place in the world to make a market of athletic popularity, but a few who have swarmed in the last half dozen years don’t seem to understand.”

Anson received his greatest blow on July 16, 1908. The McChesney family canceled the lease on the land beneath Anson’s Park and took complete control of the ballpark. Anson, now a visitor in the park that bore his name, kept the Colts together, perhaps because playing baseball was the only thing he knew how to do.

Anson’s Colts limped through three full seasons, finally giving up the ghost in late 1909. In one of their final outings, they took on the Cubs’ second-stringers at West Side Park in a game played to benefit the old captain.

A cold October wind blew off the lake, and fewer than 1000 fans were scattered across West Side Park’s 15,000 seats. Anson strode to the plate as a pinch hitter in the fifth inning and hit an easy grounder to Del Howard at second base. Howard booted it, allowing Anson to huff safely into first. Howard later claimed the ball was “too hot to handle.”

Before the 1910 season, the MacChesneys leased Anson’s Park to H.C. Ostermann, who had made his fortune manufacturing railroad cars. Ostermann put Jiggs Donahue, a former White Sox first baseman, in charge of his team, which he rebranded as the Red Sox. The team lasted a single season. Donahue died in an insane asylum in 1913, suffering from syphilis.

The semi-pro craze was over. Grandstands all over Chicago disappeared. The diamonds and outfields were plowed up and paved over to make way for homes and businesses.

The MacChesneys announced plans to subdivide the tract at 61st Street and Champlain Avenue, valued at over $150,000. In early May of 1911, a wrecking crew demolished the great steel grandstand that had consumed Cap Anson’s money. It was less than four years old.

Today, the corner of 61st and Champlain, where a few fans once paid a quarter to enter Anson’s Park, is empty. The surrounding buildings are a mix of old apartments, newer townhomes, and businesses. The ground on which Cap Anson built his mighty steel grandstand hosts a daycare center, a hair braiding salon, a trophy and plaque store, and the office of Southside Together Organizing for Power.

The corner of 61st Street and Champlain today. Google Street View.

The corner of 61st Street and Champlain today. Google Street View.

Anson never recovered from the financial debacle of Anson’s Park. He eventually found a steady income on the Vaudeville circuit, performing with Adele Cherry and her sister, Dorothy Dodge.

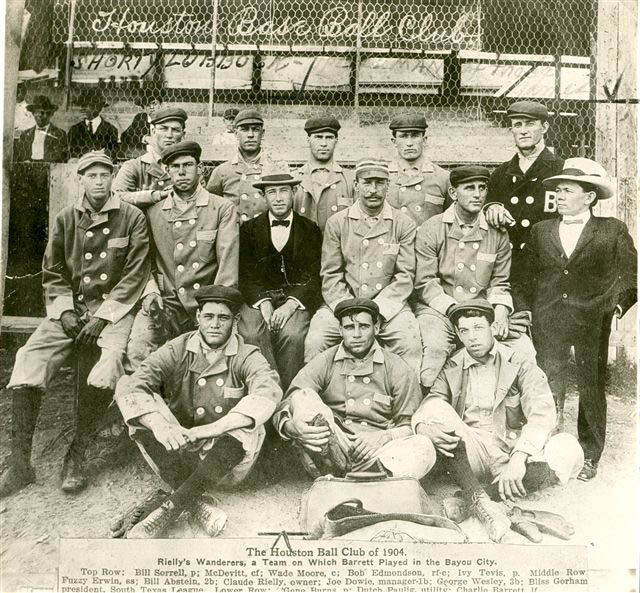

Adrian C. Anson died in 1922. When told of his passing, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis exclaimed, “Not Pop Anson? You can’t mean my old pal Pop is dead? Oh, I just can’t say anything. He was such a wonderful fellow. And to think that he’s dead.”