The Charlotte Hornets Were (Probably) Throwing Games in 1912

Something fishy took place in the Class D Carolina Association in 1912. The Charlotte Hornets were probably throwing games, losing intentionally for reasons unknown.

Something fishy took place in the Class D Carolina Association in 1912. The Charlotte Hornets were probably throwing games, losing intentionally for reasons unknown.

The sports editors of the newspapers that covered the Carolina Association dropped hints of rotten playing. They sprinkled their columns with allusions to mysterious misplays and inexplicable decisions.

The breadcrumbs strewn by the writers remain within the digitized folds of the century-old papers, a barely-marked trail that leads the modern-day researcher around a basepath that begins in North Carolina, winds through Pennsylvania, and ends in speculation.

If an organized effort to throw games existed, Charlotte pitcher Jack Sheesley, regarded as one of the best pitchers in the league, stood at the center of the scheme.

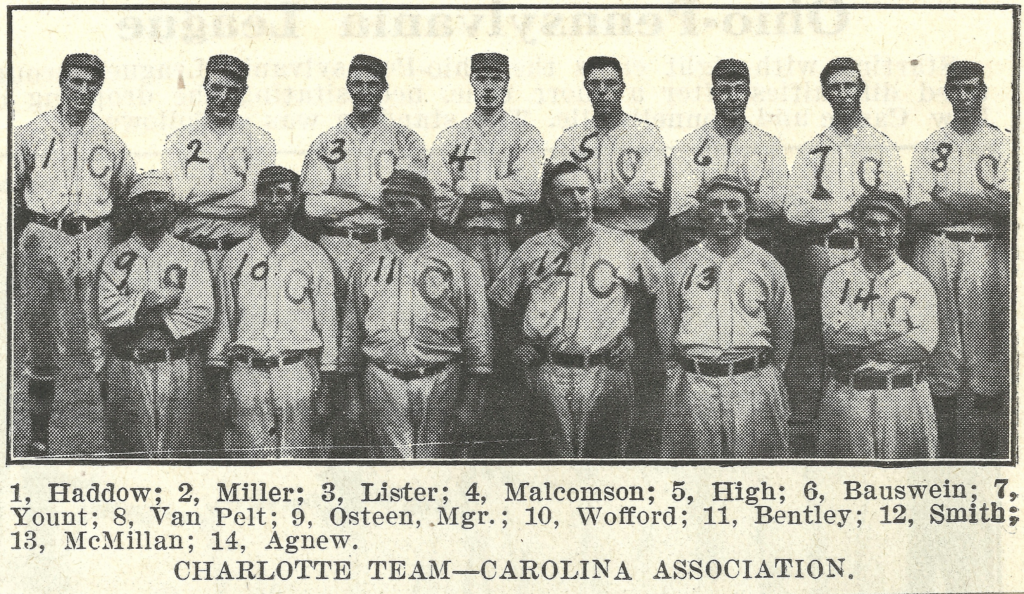

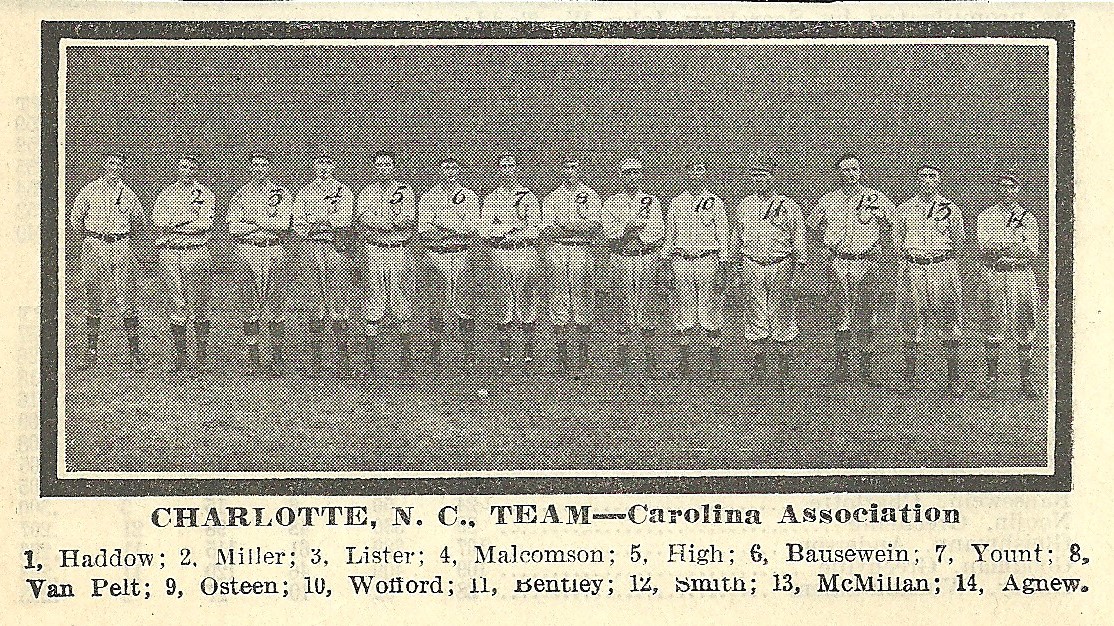

The Charlotte Hornets late in the 1912 season after Jack Sheesley had departed. The home uniforms were white with blue pinstripes and trim. The road uniforms were gray with green pinstripes and trim. The Charlotte Daily Observer described the uniforms as “striking in appearance.”

The Charlotte Hornets late in the 1912 season after Jack Sheesley had departed. The home uniforms were white with blue pinstripes and trim. The road uniforms were gray with green pinstripes and trim. The Charlotte Daily Observer described the uniforms as “striking in appearance.”

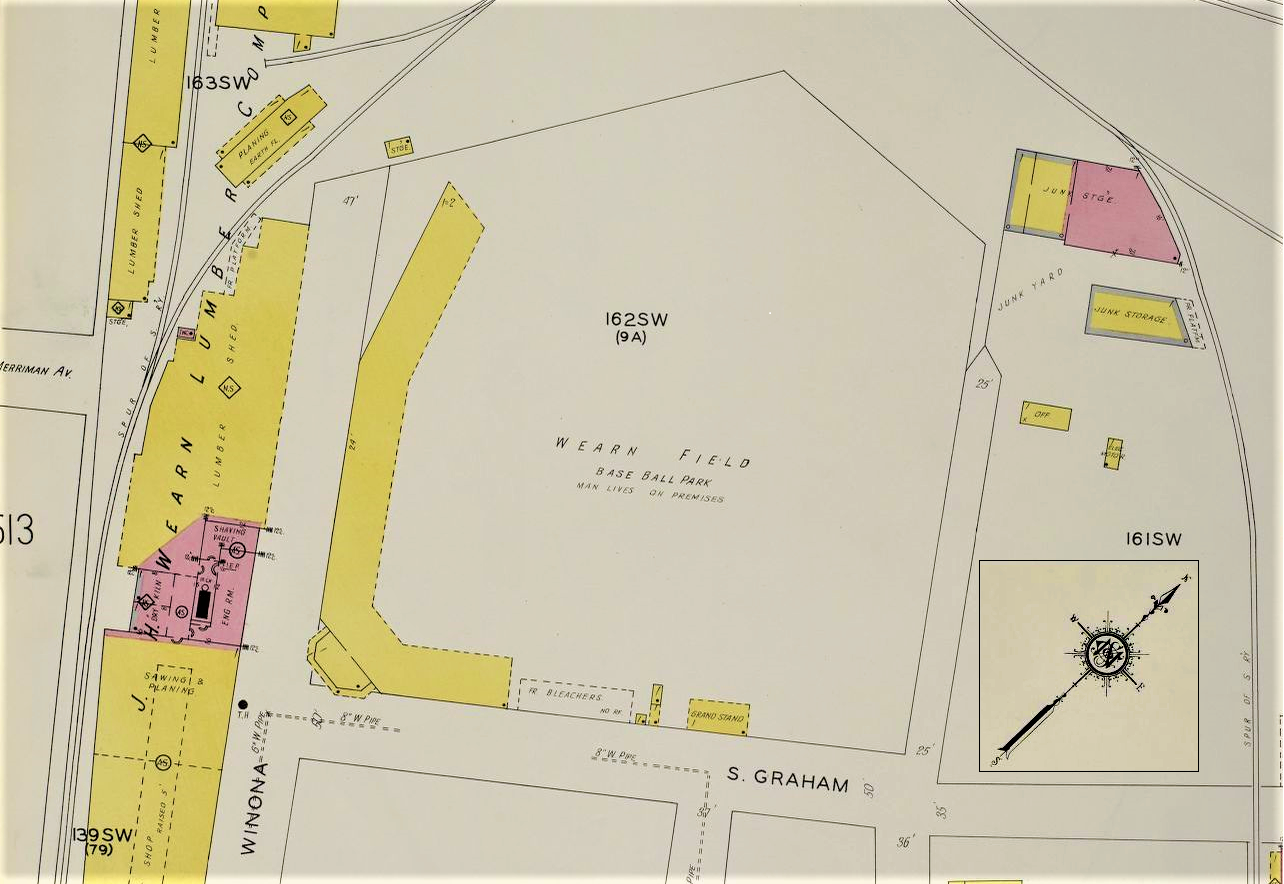

The Hornets’ first game of the 1912 season, played Thursday, April 25, against the Anderson Electricians in Charlotte’s Wearn Field, provided a template for future endeavors.

Sheesley drew the opening-day honors and pitched well through the first eight innings. At the top of the ninth, the Hornets led 3-2. Charlotte proceeded to give up three runs in an effort that exceeded the sloppiness expected in a typical Class D game.

Anderson’s initial ninth-inning batter, catcher Krozer Milliman, smacked a double off the left field fence, barely missing the Bull Durham sign. Striking the bull on the fly would have earned Milliman $50, equal to half a month’s salary.

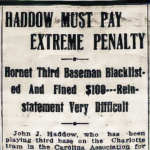

Electricians pitcher Ernie Wolf (spelled Wolfe in the newspapers) followed with a sacrifice bunt. Sheesley and first baseman August Boyne watched the ball roll between them unfielded in what the Charlotte Evening Chronicle dubbed “a revival of the Alphonse and Gaston stunt.” Wolf was safe at first as Milliman chugged into third. Wolf immediately stole second.

Frederick Burr Opper’s Alphonse and Gaston, American Journal Examiner, 1906.

Frederick Burr Opper’s Alphonse and Gaston, American Journal Examiner, 1906.

Sheesley now faced the top of Anderson’s order as leadoff batter William Kelly, a .316 hitter in 1911, walked to the plate. Kelly singled, scoring Milliman to tie the game and moving Wolf to third. Kelly proceeded to steal second.

Anderson’s Frank Spitznagle grounded to Charlotte second baseman Johnny Agnew, who scooped up the ball and gave chase to Kelly, tagging him between second and third as Wolf held at third and Spitznagle continued to second.

Curtis McCoy, a .314 hitter in 1911, then sent a grounder to Harry Siegfried at short. Siegfried fielded the ball and heaved it home, where catcher Bill Malcomson (spelled Malcolmson in the newspapers) awaited the throw.

“McCoy cracked one to Siegfried and he threw something less than a furlong over Malcolmson’s head,” Julian Miller, the 26-year-old sports editor of the Charlotte Daily Observer, reported. The Evening Chronicle said, “McCoy shoved a nice little bounder to Siegfried, who slung the globule to the grandstand.”

Wolf and Spitznagle crossed the plate while Malcomson chased the ball, and McCoy cruised into second. Anderson now led 5-3.

Red Owens, Anderson’s cleanup hitter, sent a roller to Hornets player-manager Champ Osteen at third. Osteen let the ball pass between his legs. Owens made it to first, and McCoy pulled into third.

Malcomson subsequently caught McCoy straying off base for the second out, and a long fly to center ended the inning. The Hornets went three-up-three-down in the bottom of the ninth, giving Anderson an unexpected win.

The Observer’s Miller, perhaps sensing that all was not on the level, said, “The Hornets graciously gave the victory to Anderson.”

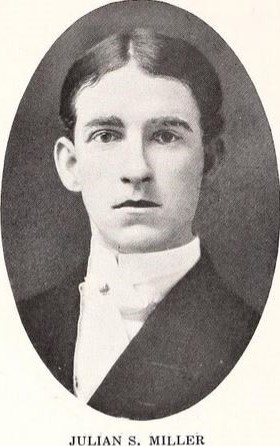

Julian Sidney Miller, sports editor of the Charlotte Daily Observer, as an Erskine College student in 1906. Miller was known to his friends as “Jute.”

Julian Sidney Miller, sports editor of the Charlotte Daily Observer, as an Erskine College student in 1906. Miller was known to his friends as “Jute.”

The items that cost the Hornets a win against Anderson – unfielded balls, wild throws, and surrendered hits at critical moments – became trademarks of Sheesley’s future losses.

A modern fan might note Sheesley’s stubborn refusal to issue intentional passes with first base open. Three times he pitched to batters with first empty and runners on second and third. Each time, a walk would have set up a force out at home, possibly a double play. But the intentional walk was not the common stratagem it is today, and none of the journalists who described the game mentioned its absence.

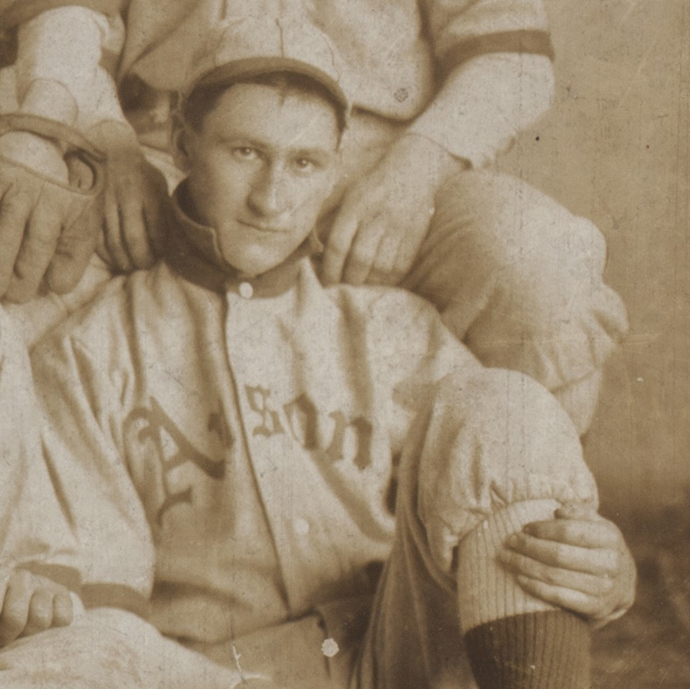

Charlotte pitcher Jack Sheesley. Charlotte Daily Observer, July 5, 1912.

Charlotte pitcher Jack Sheesley. Charlotte Daily Observer, July 5, 1912.

John Dewitt Sheesley was a 24-year-old Pennsylvanian. His father ran a building supply company in Johnstown. Known as “Jack,” he had brown hair and brown eyes, stood five feet seven inches tall, and was described as “an ambitious player and a companionable fellow.” He threw a “fadeaway” – probably a screwball – and a “mysterious drop ball” – probably a changeup.

Sheesley entered professional ball in 1909 with Sunbury of the Atlantic League, an unaffiliated circuit based in Pennsylvania. He pitched for the Johnstown and Lancaster clubs of the Class B Tri-State League in 1910 and opened the 1911 season with Youngstown of the Class C Ohio-Pennsylvania League.

Released by Youngstown, Sheesley arrived in Charlotte in May of 1911. Charlotte’s manager, Lave Cross, was familiar with Sheesley: Cross had managed the Atlantic League’s Shamokin club in 1909 when Sheesley was with Sunbury. Sheesley probably signed for about $100 a month.

After compiling a 15-15 record with Charlotte in 1911, Sheesley thought a nice raise was in order. Champ Osteen, Charlotte’s new player-manager who had replaced Lave Cross, thought otherwise.

In the days of the reserve clause, contracts were non-negotiable. Each January, the club mailed a player his contract with the amount they were willing to pay for his services filled in. The player could sign and return the contract or quit professional baseball. The reserve clause permanently tied the player to the team that owned his contract until he was sold, traded, or granted his unconditional release. A player who failed to return his signed contract promptly could be fined $100.

Sheesley delayed returning his 1912 contract. By February 21, he was officially a holdout. But three days later, the Evening Chronicle happily reported that the pitcher had signed on. When Charlotte’s spring training opened in late March, Sheesley stood present and accounted for.

What transpired that induced Sheesley to sign his contract is unknown. Something or someone made Sheesley decide that pitching for the Hornets would be worth his while, even if his monthly pay was less than he wanted. But with an obvious ax to grind, Sheesley was a perfect foil for anyone who wanted to cost the Hornets a few games.

In his second start of 1912, Sheesley proved that he was still an excellent pitcher as he shut out the Greensboro Patriots 1-0, surrendering just two hits over ten innings. But he followed it up with a 1-4 loss to the Winston-Salem Twins that involved an unfielded bunt, a wild throw to third by Sheesley that allowed a run to score, and an easy single that became a triple when it passed between left fielder Budson Weiser and center fielder Gus Hillix who, in the words of the Winston-Salem Journal’s writer, “were playing hail-over.”

“We are rapidly approaching the conclusion that Jack Sheesley has both good and bad days,” the Observer’s Julian Miller noted.

Sheesley and the Hornets were at least artful in their subterfuge, encasing their miscues in an aura of plausible deniability. Over in Winston-Salem, Twins pitcher Ray Hartranft (usually spelled Hartfrandt in the newspapers), unhappy with his contract and seeking an unconditional release, abandoned all pretense of respectability.

In an April 30 game against the Greenville Spinners, Hartranft opened the first inning by yielding four walks, a hit batter, and a single. Winston-Salem’s Twin-City Daily Sentinel dubbed Hartranft’s work “disgusting.”

One week later, in the third inning of a game against Spartanburg, Hartranft walked three batters in a row. According to the Daily Sentinel, “Manager [Charles] Clancy and the fans were thoroughly convinced of the Dutchman’s intentions and when he was called from the mound he promptly threw the ball against the grandstand. He went to the bench amid a shower of hisses.”

Clancy fined Hartranft $25 and suspended him for the remainder of the year, a move that kept Hartranft under contract without pay.

Hartranft was, like Sheesley, a Pennsylvanian. The Carolina Association was full of men who had grown up in Pennsylvania or played minor league or semi-pro ball there. They were tough customers accustomed to hard work and rough language. Examining the shenanigans in Charlotte, one finds a Pennsylvanian on every base.

Sheesley and catcher Bill Malcomson had been teammates on the Johnstown club of the Tri-State League.

Second baseman Johnny Agnew was another Tri-Stater. He and Sheesley had been together on the Lancaster club. Agnew was a personal friend of Sheesley’s. Charlotte signed Agnew in 1911 on Sheesley’s recommendation.

First baseman Gus Boyne hailed from Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, and played semi-pro ball around the state. In 1909, Boyne jumped from one semi-pro team to another, failed to return his original team’s uniform, and found himself in the hoosegow, charged with theft.

Charlotte Hornets second baseman Johnny Agnew eludes a pickoff in Charlotte’s Wearn Field. Charlotte Daily Observer, July 30, 1912.

Charlotte Hornets second baseman Johnny Agnew eludes a pickoff in Charlotte’s Wearn Field. Charlotte Daily Observer, July 30, 1912.

Sheesley tallied three straight wins in the first two weeks of May. Then, using methods eerily similar to those employed on Opening Day, he handed a game to the Spartanburg Red Sox.

Sheesley took a 0-0 tie into the fifth inning. After giving up a single and a fielder’s choice, he faced Jim Kelly with a man on second and first base open.

Kelly, a 200-pound Pennsylvania ironworker known as The Smiling One, was among the Carolina Association’s best hitters and most popular players. Once again, Sheesley had the opportunity to set up a force by walking an excellent hitter. This time, it was obviously the preferred choice.

“Sheesley started as if he was going to pass Jim purposefully,” Julian Miller reported, “but after tossing one wide, he put the next over and Jim put it out of reach of anybody.” Kelly’s long single brought home the runner on second to give Spartanburg a 1-0 lead.

“If anyone has seen Sheesley’s cunning lying around anywhere, its return to the owner will be greatly appreciated by him,” Miller quipped.

In the following frame, with Spartanburg runners on second and third and no outs, Charlotte second baseman Johnny Agnew fielded a grounder and made an “unearthly heave to the plate.” Two runners came home while catcher Malcomson chased the ball. Sheesley then surrendered four singles in a row to give the Red Sox five runs in the inning and a 6-1 win.

Sheesley’s pitching ability returned in his next game. He shut out the Greensboro Patriots 1-0, scattering four singles across nine innings and walking none. But four days later, ineptitude at an inopportune time again prevented Sheesley from collecting a win.

Pitching at home against Anderson, Sheesley and the Hornets led 4-2 going into the ninth inning. Charlotte first baseman Gus Boyne badly booted a grounder from Anderson’s Gus Gleischman, with the batter reaching second base. Anderson’s Red Owens flied to right fielder Togo Bentley, but Bentley dropped it. Owens stopped at first as Gleischman made it to third.

A sacrifice fly brought Gleischman home, after which Owens stole second. With Anderson’s pitcher on deck and first base open, an intentional walk to batter Krozer Milliman was in order – by today’s standards, at any rate. But Sheesley pitched to Milliman, who singled to score Owens and tie the game. The game remained knotted 4-4 through twelve innings when the umpire called off the affair due to darkness.

Sheesley’s next loss featured, in the words of the sports editor of the Greensboro Daily News, “something seldom seen in baseball.”

Playing the Greensboro Patriots, with the game tied 1-1 in the second inning and a runner on first, Sheesley whipped a pickoff throw to first baseman Boyne. The ball hit Boyne in the pit of his stomach and bounced into right field. The runner at first base came around to score, giving Greensboro a lead that they never surrendered. The Hornets were finding ever-more-creative methods of losing.

A few days after Sheesley bounced the ball off Boyne’s gut, a strange story swept the streets of Charlotte: Pennsylvanians Sheesley, Boyne, and Malcomson, along with Hillix, a Missourian, had been released. Charlotte club president J.H. Wearn denied the rumor, but its existence suggests that whispers of – something – were making the rounds.

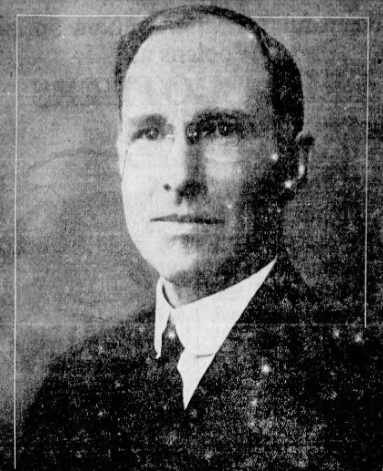

Joseph Henry Wearn, president of the Charlotte Base Ball Club. Charlotte Daily Observer, February 20, 1916.

Joseph Henry Wearn, president of the Charlotte Base Ball Club. Charlotte Daily Observer, February 20, 1916.

With rumors of his release afloat, Sheesley’s abilities abandoned him completely in his next start. Pitching six and two-thirds innings, he gave up five runs on 11 hits, including three home runs and a double, while walking five and drilling a batter as the Hornets lost 7-3 to the Winston-Salem Twins.

Though the Hornets occasionally lapsed into incompetence, they were, overall, playing good ball. On June 8, Charlotte held down second place in the Carolina Association, four games behind the Anderson Electricians. But that afternoon, with Sheesley on the mound, the Hornets lost to the Greenville Spinners in what the Charlotte News described as “a conglomeration of hits, errors, bonehead plays, and defeat.”

In the third inning, with the game tied 0-0 and the Spinners batting, first baseman Boyne booted a grounder all the way over to Agnew at second. Agnew picked up the ball and heaved it beyond Boyne’s reach, allowing the runner to reach second.

The next batter hit a comebacker to Sheesley, who chased the runner down between second and third as the batter reached first.

The third hitter sent an easy double-play grounder to Charlotte third baseman Joe Wofford. Wofford scooped it up and sent the ball over second baseman Agnew’s head into right field, both runners being safe. The “throw over the head” had become a regular feature of Sheesley’s losses. A long single brought the runners home to give the Spinners a two-run lead.

The Hornets came back to tie the game in the fifth inning, but Sheesley subsequently surrendered a double and a single to hand the Spinners a 3-2 win.

The Hornets were excellent fielders when they wanted to be. Over the first two months of the 1912 season, they compiled a .954 fielding average, good for second-best in the league, a single percentage point behind the league-best Spinners. Yet the Hornets had an infinite capacity to make interesting errors whenever one was needed to ensure a loss.

Misplays were not unusual for Class D games played on bumpy, unmanicured diamonds by fielders whose gloves were little more than leather oven mitts. The Hornets’ errors, considered individually, were unremarkable. The overall pattern of behavior, though, suggests that the results were less than random.

Lackadaisical play also contributed to the losing efforts.

Sheesley faced the Winston-Salem Twins in Wearn Field on June 12. Describing the less-than-enthusiastic play of the Charlotte outfielders, the Winston-Salem Journal noted that “the slow work of the outfield allowed hits to be stretched.” The Charlotte News said the Twins were twice “credited with extra base swats when the hit would have been nothing more than a single.” And the Greensboro Daily News offered a blunt assessment: “The Charlotte outfield’s work was simply rotten.”

Despite the lack of outfield support, Sheesley took the mound in the seventh inning nursing a 2-1 lead. He immediately gave up four runs in an effort that involved three hits and three errors, including a dropped fly by center fielder Hillix. A final run in the eighth gave the Twins a 6-2 victory.

Charlotte Daily Observer, June 13, 1912.

Charlotte Daily Observer, June 13, 1912.

The Observer’s Julian Miller, who seemed from opening day to suspect that all was not on the level when Sheesley toed the slab, said, “The game was tossed away in the seventh inning and ‘tossed away’ at least connotes that the Hornets did not allow the Twins to win on the mere manhood.” The result, Miller wrote, left “something of a bad taste lingering around under the palate.”

In Sheesley’s next start, a June 17 game against the Spartanburg Red Sox at Wearn Field, he and the Hornets demonstrated how a loss could require effort at both ends of the innings.

Charlotte scored first and was leading 1-0 in the top of the third. With two out, Sheesley walked Spartanburg’s Joe Kipp. The next batter sent an easy fly to right. Charlotte’s Togo Bentley somehow managed to muff it and could not return the ball before Kipp scampered around the bases to knot the game.

The Hornets had an excellent chance to take the lead in the bottom of the eighth inning. Sheesley walked, then went to second on a sacrifice. A single by Bentley sent Sheesley to third. He may have been able to make it home, but according to Julian Miller, Sheesley “failed even to attempt to score on Bentley’s hit.” A walk to Champ Osteen loaded the bases.

With one out, the next batter sent a shallow liner over third base and Sheesley broke for home. He was far from the base when the ball was flagged down on the fly by Spartanburg left fielder John Wagnon. Sheesley trotted back to third, then, inexplicably, he again broke for home. Wagnon pegged the ball to the catcher, who was waiting with the ball when Sheesley arrived at the plate.

“For some unknown reason the coacher on third ran Sheesley in, allowing the visitors to pull an easy double,” reported the mystified editor of the Charlotte News.

In the top of the ninth frame, with the game still tied at 1-1, the Red Sox were down to their final out with the winning run on second base. Spartanburg manager Billy Laval sent catcher Jack Coveney to the plate as a pinch hitter. Coveney, Spartanburg’s regular catcher, was a solid veteran who would bat .274 in 1912. He had been enjoying a rare day off.

Pitcher Wild Bill Clark was on deck for the Red Sox. Clark had already struck out three times that day and showed no evidence of potential improvement. Even by 1912 standards, the obvious choice called for Sheesley to walk Coveney and pitch to Clark.

If Manager Laval desired to pinch hit for Clark, the league’s 13-man roster limit constrained his choices. After Coveney entered the game, the only players remaining on the Spartanburg bench were a pair of pitchers and a recruit named Oglesby, who had never appeared in a professional ballgame. Pitching to any of them would have been a better alternative than facing Coveney.

“All that Pitcher Sheesley would have had to do was present Coveney with a walk and the chances are multitudinous to nothing that ‘Wild Bill’ Clark would not have done any damage,” Julian Miller wrote the next day.

Instead of passing Coveney, Sheesley pitched to him. In the words of the sports editor at the Greensboro Daily News, Sheesley “grooved the ball and Coveney did rest.”

Coveney whacked a single, the runner on second scored, and the Red Sox took the lead. Wild Bill shut down the Hornets in the bottom of the ninth, and Sheesley fielded another loss under illogical circumstances.

Our man at the Charlotte News alluded to a fix: “There were a number of bonehead plays on Charlotte’s part, and she practically threw the game away.”

The competent side of Sheesley returned on June 22. He easily handled the Greenville Spinners, scattering seven hits, walking one, and fanning nine in a 6-1 win as the Hornets played errorless ball.

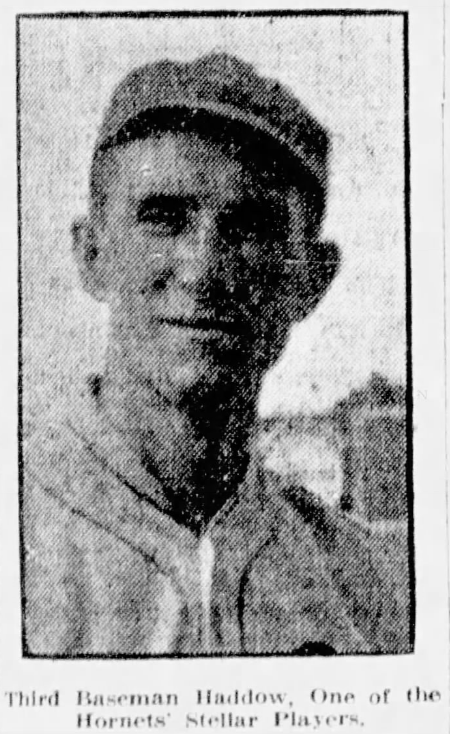

Sheesley’s final loss as a Charlotte Hornet arrived on June 27. Fifteen hundred fans filled Wearn Field and watched Sheesley lose to the Greensboro Patriots. He was assisted in the loss by third baseman John Haddow.

With Charlotte leading 1-0 in the top of the second inning, Greensboro’s Charlie Doak poled a drive to center field that nearly reached the fence.

Doak circled the bases for an official home run to tie the game, but the Evening Chronicle noted that “a fumble of the throw-in by Haddow probably allowed him an extra sack.”

The Patriots added the go-ahead run in the fourth inning when they strung together two singles and a sacrifice fly.

In the ninth inning, Haddow appeared at the plate with the bases loaded, two outs, and the Patriots still holding a 2-1 lead. He sent an easy popup to Greensboro’s third baseman to end the game.

John Haddow with the Charlotte Hornets. Charlotte Daily Observer, July 9, 1912.

John Haddow with the Charlotte Hornets. Charlotte Daily Observer, July 9, 1912.

John Haddow was a recent addition to the Hornets, having arrived in Charlotte twelve days earlier. An excellent hitter and fielder, Haddow quickly established himself as the best third baseman in the Carolina Association.

Like Johnny Agnew, Haddow was a friend of Sheesley. The two had been in the Tri-States League together in 1910 when Haddow played for the Harrisburg Senators, and Sheesley and Agnew were with the Lancaster Red Roses. And, like Agnew, Charlotte signed Haddow on Sheesley’s recommendation.

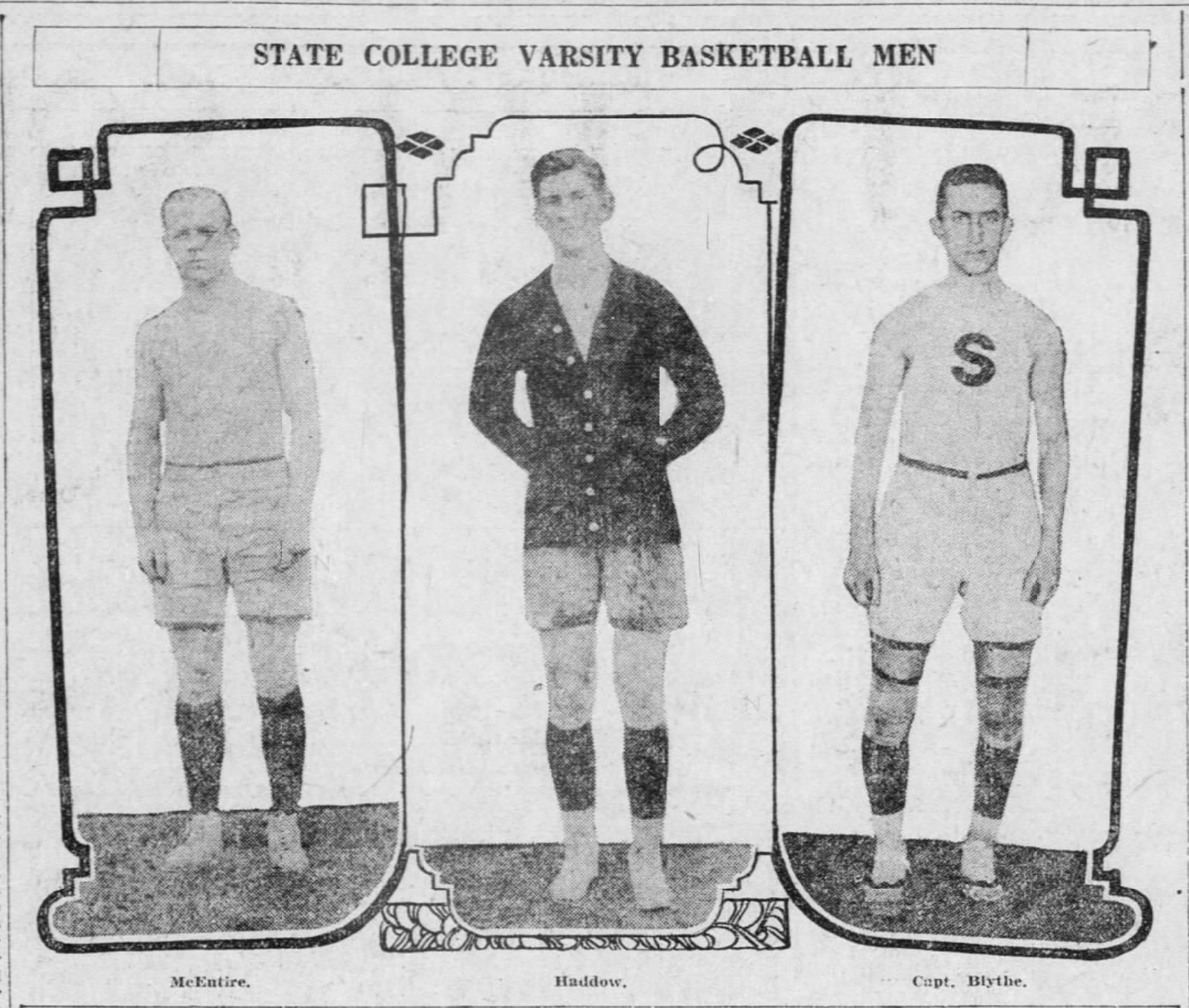

Born in Kentucky to Scottish immigrants, John Falconer Haddow attended high school in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, where his father worked for Penn Steel as a master mechanic. He starred on Lebanon High School’s baseball and basketball teams, managing both squads in his senior year. On his WWII draft registration, Haddow listed his height as 6’2” with a weight of 160 pounds.

After graduating from high school in the spring of 1909, Haddow spent the summer playing semi-pro ball with the Penn Steel team. In September, the fully-professional Harrisburg Senators signed Haddow for the 1910 season.

Undeterred by his incipient professional standing, Haddow enrolled at State College in the fall of 1909. He “jumped center” for the varsity basketball team in the winter and held down third base for the baseball team the following spring.

John Haddow (center) at State College. Pittsburg Post-Gazette, February 12, 1911.

John Haddow (center) at State College. Pittsburg Post-Gazette, February 12, 1911.

When the college baseball season ended, Haddow – still under contract to the Harrisburg Senators – took his talents to Shamokin of the independent Central Pennsylvania League. To protect his amateur standing, Haddow played as “John Black.” His true identity, though, was not a secret. The Lebanon Daily News broadcast Haddow’s signing under the headline John Haddow Joins The Shamokin Club.

On August 8, 1910, the Harrisburg Senators exercised their rights to Haddow and called him in to take over third base. At Harrisburg, he continued to play as John Black.

Black’s identity must have been common knowledge. “Black is a college boy playing under an assumed name,” the Pittsburg Post-Gazette reported. The Philadelphia Inquirer described him as “Black, the State College star,” indicating a known provenance. It should have been simple to deduce Black’s real name. How many six-foot-two third basemen played at Penn State?

Before a mid-August game, the Senators and the Trenton Tigers engaged in a “field sports” competition. Haddow placed second in the “throwing the baseball for distance” contest, heaving the ball 405 feet, four inches.

He appeared in 28 games over the final month of Harrisburg’s 1910 season, batting .222 with two doubles, two triples, and a homer.

Haddow’s play caught the attention of major league scouts. In the September 1910 draft of minor league players, the National League’s Cincinnati Reds and the American League’s St. Louis Browns claimed Black. A draw of lots sent Black to the Reds.

The Reds must have immediately relinquished their claim; by February 1911, Black was with the Browns. Harrisburg manager Kip Selbach told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that Black was the real deal: “He has a whip of steel and it is a pleasure to see him shoot the ball across the diamond. His average may not show much, but he will develop into a big leaguer or I will be a disappointed man.”

The Post-Dispatch was more or less aware of the new player’s origin story. “Black – and Black is not his real name – is a student of the University of Pennsylvania,” the paper explained, probably insulting both UPenn and Penn State.

After completing his 1910-1911 sophomore term at State College, again starring on both the hardwood and the diamond, Haddow joined the Browns in June. He recorded 53 games at first base and one at third. Overmatched at the plate, Haddow hit only .151 and struck out 42 times in 202 plate appearances. He blamed his poor showing on a badly bruised left hand.

Returning to State College for the 1911 fall term, Haddow contracted typhoid and was sent home to Lebanon. By December, he had recovered sufficiently to take a job coaching the Lebanon Valley College basketball team.

Nineteen-twelve proved a busy year for Haddow. In January, the Browns sold his contract to the Louisville Colonels of the Class AA American Association. By now, the cat was well out of the bag. “First Baseman Black, who is none other than Haddow, the former Penn State lad, has been turned over to Louisville by the St. Louis Browns,” the Pittsburg Press reported.

Black/Haddow reported to Louisville in early March but failed to impress the Colonel’s manager. On April 21, the Louisville Courier-Journal reported, “John Black was given his unconditional release because he could not be placed with any team.”

He returned to Pennsylvania and again signed with the Tri-State League’s Harrisburg Senators, who immediately loaned his services to the league’s Allentown club. Playing mostly second base and shortstop, Haddow finally recorded professional stats under his real name.

Allentown returned Haddow to the Harrisburg Senators after only 22 games. He came home bearing a batting average two points above the Mendoza Line. The Senators didn’t want him, and he was released.

On June 15, Haddow took the field for Charlotte, reuniting with his friends from the Tri-State League, Jack Sheesley and Johnny Agnew.

Few knew where Haddow had come from. Initial rumors placed his origin in Piedmont, South Carolina. But after a road trip to Anderson, the Daily Observer said, “It was first reported that Haddow was from Piedmont, S.C., but the only time he ever saw that town was from the train as he recently passed it twice.”

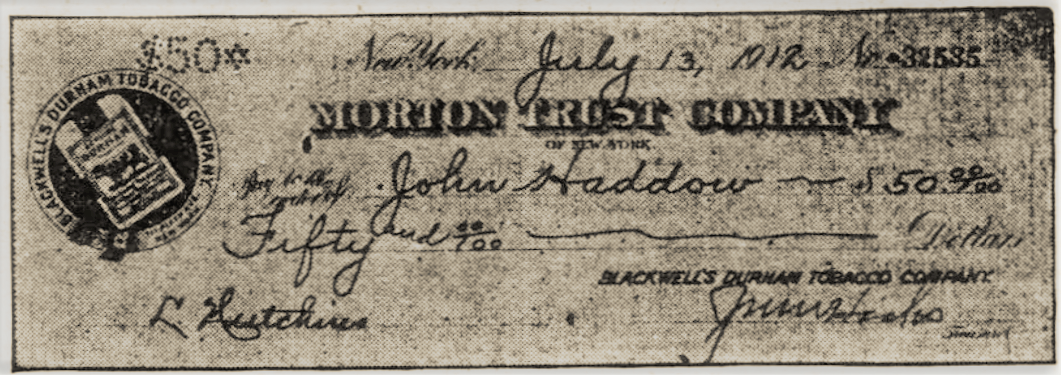

No one cared where Haddow had been sourced. He played well and became popular with the fans. On July 11, he hit a line drive into the Bull Durham sign that graced Wearn Field’s left field wall, earning a $50 reward from W.T. Blackwell and Company, makers of Genuine Bull Durham Smoking Tobacco.

Check presented to John Haddow for striking Wearn Field’s Bull Durham sign with a line drive. Charlotte Evening Chronicle, July 30, 1912.

Check presented to John Haddow for striking Wearn Field’s Bull Durham sign with a line drive. Charlotte Evening Chronicle, July 30, 1912.

The Evening Chronicle uncovered Haddow’s background a few weeks later. “It was apparent that he had seen some higher class ball than this, but the fans could not place the name of Haddow in any of the leagues over the country,” the paper told its readers. “Haddow has played in the Tri-State League and was later with the St. Louis Americans. At both places he worked under the name of Black.”

The confusion over Haddow’s identity continues into the present. Baseball Reference contains separate entries for Haddow and Black. And, hilariously, the Find-A-Grave database also contains separate pages for Haddow and Black.

Although he died on March 19, 1962, the Find-A-Grave entry for Black indicates that he passed the following day, while Haddow’s page shows him lingering until October. The database even carves up the man’s mortal remains. Haddow is correctly interred in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, while Black’s body lies 230 miles west in a suburb of Pittsburgh.

In 1912, a person of such sketchy provenance was a perfect addition to the Charlotte Hornets’ game-throwing scheme.

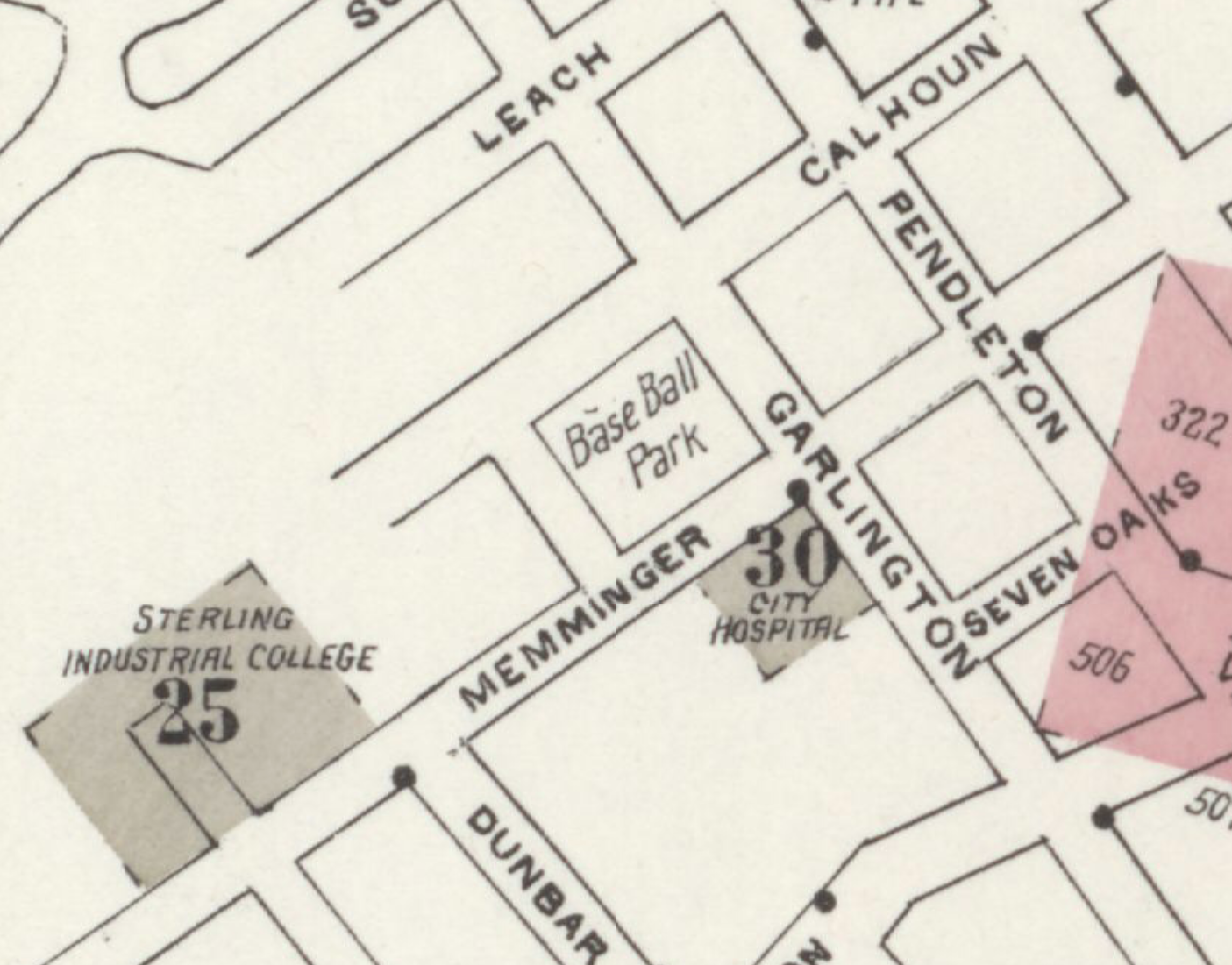

Wearn Field in Charlotte, North Carolina. Home plate was at the corner of South Graham and Winona; the right field corner was at South Graham and Commerce. The J.H. Wearn Lumber Company is across Winona. The small print below “Wearn Field Base Ball Park” reads, “Man lives on premises.” Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1929.

Wearn Field in Charlotte, North Carolina. Home plate was at the corner of South Graham and Winona; the right field corner was at South Graham and Commerce. The J.H. Wearn Lumber Company is across Winona. The small print below “Wearn Field Base Ball Park” reads, “Man lives on premises.” Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1929.

Aerial photo showing Wearn Field in 1938. Today, construction equipment is stored on the site. From Urban Planet.

Aerial photo showing Wearn Field in 1938. Today, construction equipment is stored on the site. From Urban Planet.

After the June 27 loss to Greensboro, in which Haddow’s fumble of a relay throw allowed the tying run to score, Sheesley found a way to extricate himself from the toxic situation in Charlotte. Sheesley approached Greensboro player-manager Frank Doyle and cut a deal: if Sheesley could finagle his unconditional release from Charlotte, Doyle would sign him.

In his next start, on July 3 against the Anderson Electricians, Sheesley teed up his departure by being horrendous. He gave up two runs on a walk, a triple, and a double in the first inning. After Sheesley drilled the next batter, Champ Osteen banished him to the bench. The Hornets eventually came back and won the game.

That evening, Sheesley approached Osteen and demanded his release. Since Sheesley had pitched poorly on purpose, Osteen could have suspended him without pay, preventing Sheesley from signing with another team. But Osteen had to let Sheesley go.

Sheesley had leverage: if Osteen was aware of the game-throwing scheme, Sheesley could blow the whistle on him. It was better to send Sheesley on his way and hope he kept his mouth shut. Sheesley departed the Hornets with a 6-9-1 record.

Announcing Sheesley’s release in their Independence Day editions, the local writers alluded to the issues that led to Sheesley’s departure. “He has not been in the best of spirits about his condition for some time,” Julian Miller wrote. The editor of the Charlotte News said, “He is a good twirler and in congenial surroundings he ought to go good.”

Patriots manager Frank Doyle planned to provide those congenial surroundings, but Sheesley had other ideas. The day after being released by Charlotte, he showed up in Winston-Salem, where Twins manager Charles Clancy signed him to a contract that no doubt topped Doyle’s offer and probably exceeded his Charlotte salary. Sheesley finally had the raise that he had sought back in February.

“In signing with Clancy, Sheesley gave Frank Doyle the original double cross package,” the writer for the Twin-City Daily Sentinel reported. “Until last night Doyle rested under the belief that he would join his team.”

Sheesley made an immediate, positive impact with the Twins. On July 6, he pitched a 3-0 shutout against the Greenville Spinners in the first game of a doubleheader. In the day’s second game, he came in as a reliever in the fourth inning. The Twins were leading 2-1, with a Spinner on every base and no outs. Sheesley retired the side without yielding a run. He pitched the remainder of the game, taking a 3-2 win for the Twins.

Sheesley met his old team in Winston-Salem’s Prince Albert Park on July 9. He shut out the Hornets 2-0, yielding just two hits and striking out nine. After fanning Charlotte manager Champ Osteen, Sheesley had a good laugh. Osteen, who had enjoyed a few cups of coffee in the majors, was impressed with Sheesley’s work, saying “that he had never batted offerings in the big leagues that had more on ‘em than Sheesley’s benders and twisters.”

The Greensboro Daily News announces Sheesley’s win over the Hornets, July 10, 1912.

The Greensboro Daily News announces Sheesley’s win over the Hornets, July 10, 1912.

Besides Sheesley’s laugh at Osteen’s expense, the game passed without notable incidents.

“There will naturally be a good many around here who will engage in criticism of Jack Sheesley for not doing his best as a member of the Charlotte club,” Julian Miller wrote after Sheesley’s win. “The chances are that Sheesley was afflicted with the belief that he could not win with the Charlotte team, which apparently he couldn’t.”

The next day, Miller pondered, “Strange that Jack Sheesley waited until he joined Winston before demonstrating that he had the right to the name of even being a pitcher.”

The Winston-Salem’s Twin-City Daily Sentinel defended the Twins’ new pitcher: “The truth of the matter is that Mr. Sheesley felt that he could not win games with the Hornets.” And alluding to the possibility that Sheesley’s teammates were intentionally slacking off, he added, “He also felt justified in the belief that the men associated with him were not giving him the support in the games he worked to which he was entitled.”

The lack of “support” provided to Sheesley is evident in the number of errors the Hornets created when Sheesley was on the mound.

Between opening day and Sheesley’s departure on July 3, the Hornets played 60 games. Sheesley was the pitcher of record in 16 (6 wins, 9 losses, 1 tie).

In the 44 “non-Sheesley games,” the Hornets averaged 2.00 errors per game in wins and 1.93 errors per game in “non-wins” (losses plus ties). But in the 16 “Sheesley games,” the Hornets averaged a minuscule 0.50 errors per game in wins, compared to a whopping 2.50 errors per game in non-wins.

When Sheesley was not pitching, the Hornets made about the same number of errors whether they won or lost. When Sheesley pitched, the Hornets made significantly more errors in non-wins than in wins.

When the Hornets lost or tied with Sheesley on the mound, they made significantly more errors than when they lost or tied behind their other pitchers.

Given the weird and convenient nature of many errors committed during Sheesley’s non-wins, it is difficult to believe they were random occurrences. And, given that Sheesley’s friends and fellow Pennsylvanians were responsible for many of the errors and miscues, a natural conclusion is that Sheesley was an active participant in the shenanigans.

Sheesley faced the Hornets for the second time on July 12 in Charlotte’s Wearn Field, losing 3-5. The local fans gave him a good jeering, but the game itself was conflict-free.

Doc High with the Tidewater League’s Norfolk Rookies. Washington Evening Star, May 24, 1911.

Doc High with the Tidewater League’s Norfolk Rookies. Washington Evening Star, May 24, 1911.

Nearly every southern team harbored at least one Doc or Dock. The Charlotte Hornets’ 1912 roster included Dlay Blake “Doc” High, a 21-year-old pitcher. In Sheesley’s last appearance as a Hornet, from which he departed amid an intentionally terrible first inning, Doc High stepped in and pitched the remainder of the game.

High was a true Southerner, born in Anson County, North Carolina, and raised in Columbia, South Carolina. He inherited his odd first name from his father and later passed it on to his son. The origin of his nickname is lost to history. Some newspapers referred to him as D.B., Dee, or Hugh.

Standing six feet tall and weighing 170 pounds, with piercing blue eyes below a shock of black hair, High was considered a big guy in his era. He had a nice curveball, hit well, and could play first base, third, or the outfield.

In 1909, when he was 18, High joined the Mechanics, a fast semi-pro team based in Columbia. He stayed with the Mechanics through 1910. At the tail end of the 1910 season, High appeared in a single game with the Augusta Tourists of the Class C South Atlantic League.

The following season, 1911, High was the opening day pitcher for the Norfolk Rookies of the unaffiliated Tidewater League (not a member of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues). Talent-wise, the Tidewater circuit was on par with a bad Class D league.

The Rookies sold High’s contract to the American League’s Washington Nationals in late May. The reported sale price of $2000 was very large for a young pitcher in the low minors, but no money changed hands. The sale was contingent on High sticking with the Nationals, which he did not.

High joined the Nationals on May 30, spent a week on the bench without appearing in a game, and was released on June 8. “He has been worked in morning practice, and any other value he may have had was nullified by his extreme wildness,” the Washington Post reported. By June 15, High was back on the mound for Norfolk.

The Tidewater League was sinking, and players began abandoning ship for greener shores. Since the circuit was not part of the National Association, there was no reserve clause to bind them to their teams.

The Asheville Mountaineers of the Class D Appalachian League announced on July 3 that pitcher D.B. High of the Tidewater League’s Norfolk club would join the team “later in the week.” One week later, the Mountaineers said that High would “probably” arrive that day. But that afternoon, High pitched in Hampton, Virginia, where the Norfolk Rookies defeated the Old Point Artillerymen.

What transpired between High and the Mountaineers, and whether he officially signed a contract, is unknown. At any rate, High did not appear in an Asheville uniform that season.

Continuing his 1911 wanderings, High next turned up on June 20, pitching for the Richmond Colts of the Class C Virginia League. Overmatched by Class C competition, High was released on July 30 bearing a 0-3 record. “High was many pumpkins in the Tidewater, but failed to deliver for Richmond,” Gus Malbert of the Richmond Times-Dispatch wrote. “He is a great big boy and with proper handling will make somebody a good man.”

Back in Columbia, High landed a tryout with the Class C South Atlantic League’s Macon Peaches, who were in town for a series with the Columbia Comers. Pitching two-thirds of an inning in relief on August 12, High gave up no hits but walked one, hit a batter, and made two wild pitches.

His performance somehow warranted another look. Three days later, he pitched a complete game in Macon, losing 0-4 while surrendering eight hits, including back-to-back home runs. The game was High’s last official appearance in any league above Class D.

High returned home and re-entered the semi-pro ranks. In early September, pitching for a club in Eau Claire, a suburb of Columbia, he faced a team sponsored by the YMCA. High mowed down the hapless amateurs, allowing no hits and striking out 22. A pair of walks was the only blemish on his near-perfect game.

He spent the remainder of the season pitching for his old team, the Mechanics.

During High’s 1911 season, he migrated from Columbia to Norfolk to Washington, back to Norfolk, to Richmond, to Macon, and finally back to Columbia. His wanderings were typical of players in the low minors. They were drifters, following hints of jobs and fleeing from failing franchises. Few players enjoyed the luxury of spending more than a couple of seasons in the same city.

The following March, Champ Osteen, the new manager of the Charlotte Hornets, brought ten pitchers to spring training, hoping half would be worth keeping. Doc High was among those snared in Osteen’s net.

High had no prior association with Sheesley or his pals. But he slid easily into the production of suspicious losses.

High’s first loss followed the Sheesley Template. Going against the Anderson Electricians on May 29, High struck out nine and allowed only three hits, yet lost 0-1 after a pair of well-timed misplays.

With the score 0-0 in the sixth inning, Anderson pitcher Ernie Wolf sent an easy fly to center. The assembled journalists agreed that center fielder Barney Cleveland, subbing for Hillix, should have caught the ball. But Cleveland let the ball drop, and Wolf scampered to second.

Wolf took third on a weird passed ball. “High threw Malcolmson a ball around his shoulders, which for some reason he refused to try after,” the Charlotte News reported. The Evening Chronicle described Wolf’s advance as a “comp ticket.”

A clean single brought Wolf home to tally the game’s only run.

High’s next loss completely lacked subtlety. He took the mound against Winston-Salem on June 5 and promptly gave the game away.

High bagged two outs in the first inning, then loaded the bases before surrendering four runs. He improved on his schtick the next inning, achieving two outs before loading the bases and giving up five runs. Osteen pulled High and sent Boyne to the mound as a sacrificial lamb. The game ended with a 4-12 Charlotte loss. The Charlotte News labeled the endeavor a “farce.”

“High seems to be one of those pitchers who can pitch sometimes and who can’t pitch other times,” Julian Miller remarked. It was a useful skill if a pitcher needed to lose specific games.

High pitched well in his next eight appearances, recording seven wins and a tie. But in a July 15 game against Anderson, he again showed no interest in winning. Pitching six innings, he gave up nine runs, eight hits, seven walks, and hit a batter. Haddow chipped in two critical errors.

High yielded one run in the first inning and three in the second. In the fourth inning, High and Haddow helped the Electricians transubstantiate one hit into five runs.

Haddow misplayed a slow roller, allowing the batter to reach first. Three consecutive walks brought the runner home and loaded the bases. A double cleared the sacks. Another error by Haddow placed runners at first and second. Two more walks by High brought in the inning’s fifth run.

Osteen entered the box in the seventh inning and held the Electricians scoreless over the final frames as Charlotte lost 4-9.

Julian Miller again noted High’s seemingly intentional inconsistency: “He has an abundance of curves and there is no speedier twirler in the circuit, but High frequently does not feel like pitching and at those times he loses.” Despite High’s obvious and oft-occurring lack of effort, Osteen kept handing him the ball.

After Sheesley’s early-July departure, High appears to have replaced him as the Hornet’s head game-thrower. High had an excellent record of 12-2-1 on July 11. He ended the season 14-8-1.

Greenville’s League Park (center). Sanborn Fire Insurance map, 1913.

Greenville’s League Park (center). Sanborn Fire Insurance map, 1913.

Temperatures rose, and a shell of humidity encased the Piedmont Plateau. White cotton shirts soaked through, and only the most dedicated fans were willing to wilt in the heat of the resinous grandstand. The minimal sense of decorum that existed on Class D diamonds melted away in the heat of late July.

The Carolina League umpires allowed umpires to fine players on the spot for behavior that delayed or disrupted the game. The unofficial protocol called for the player to be fined before being ejected. Some umps were notoriously quick with both the tariff and the hook.

The second-place Hornets faced the last-place Spinners in Greenville’s League Park on July 24. High took the mound for Charlotte. Umpire George Bowers called the balls and strikes. Bowers was a big guy, a former first baseman and outfielder from Pennsylvania who had played minor league ball for several seasons before retiring with a knee injury.

In the bottom of the third inning, High recorded two outs before Greenville center fielder Lonnie Noojin stepped to the plate. Noojin worked High to a full count before Bowers called “Ball four!” on a pitch that High thought was “Strike three!”

“High could not see as the umps did and started to discuss the question,” the Greenville Daily News reported. “Umpire Bowers then placed a $5.00 fine on the pitcher and he became all the more angered. The umps then raised the fine to $10.00 causing the visiting twirler to lose his head entirely.”

Bowers gave High the hook. High rushed in and gave Bowers a shove, then stepped back and hurled the ball at the umpire’s head, missing it by mere inches. A squad of policemen entered the fray and escorted High to the hoosegow, where he was fined $10 in the city court.

The matter came to the attention of the Carolina League president. The newspapers reported that High faced suspension for the remainder of the season. But the Carolina League president happened to be Charlotte Hornets President J.H. Wearn.

J.H. Wearn wasn’t about to deprive his team of one of its best pitchers, even if that pitcher had a habit of quitting while still on the mound. Wearn fined High $50 and allowed him to keep playing. “The offense of which High is guilty is heinous and cannot be tolerated by any lesser degree of punishment than this,” Wearn said. And while Wearn could not tolerate a lesser punishment, a greater punishment – a suspension – would have been justified.

The next day, Champ Osteen sent High to the mound to face the Spartanburg Red Sox. High was in a bad mood, having just forked over about two-thirds of a month’s salary. The presence behind the plate of umpire Bowers did not help his mettle.

The Winston-Salem Journal described the proceedings under the sub-head, High Attempts to Pitch But Was Removed For Grouchiness.

Headline in the Winston-Salem Journal, July 26, 1912.

Headline in the Winston-Salem Journal, July 26, 1912.

Although High evidenced the demeanor of a petulant schoolboy, the Red Sox did little with whatever he was serving up. He “puffed and pouted and got away with it,” the Charlotte News said. Going into the fifth inning, the Hornets led 3-1. At that point, High decided to call it a day.

“He sulked throughout the entire game and in the fifth seemed to lose every vestige of interest as well as his effectiveness,” the Evening Chronicle reported. High surrendered four hits, a walk, and a wild pitch, which the Red Sox translated into four runs.

Champ Osteen sent High to the bench, and the game ended with a 4-5 Charlotte loss. It may not have been a pre-determined loss, but High had again demonstrated that he could lose whenever he wanted to.

High did not start again until August 1, when he toed the slab against the Anderson Electricians. In an easily winnable game, High and Haddow managed to snuff a Hornets’ rally and snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

High pitched well, or at least the Electricians failed to take advantage of his offerings. But the Hornets were likewise unable to connect. The Electricians scored two runs in the top of the sixth on a single, a walk, and a double to give them a 2-0 lead.

In the bottom of the sixth, High led off with a single to left and advanced to second on a wild pitch. The next batter, Johnny Agnew, tapped one back to Anderson pitcher Ira Hogue. Hogue spun around to check the runner at second and was amazed to see High standing a few feet from the bag and making no attempt to move toward either second or third. A toss to the second baseman and High was an easy out as Agnew pulled into first.

Haddow stepped to the plate and tripled, plating Agnew to make it a 2-1 game. The game would have been tied if not for High’s freeze-frame act.

“Then the worst play of the afternoon was enacted,” Julian Miller moaned. With manager Champ Osteen at the plate, Haddow broke for home on an apparent squeeze play. But Osteen, who had presumably called for the squeeze, “did not even make a motion toward hitting the first ball pitched,” suggesting that Haddow acted on his own hook. Haddow pulled up, reversed course, and fell in the dirt where he was tagged.

The Hornets scored no subsequent runs, and the game ended with a 2-1 Anderson win.

“To express it clearly it seemed as if the Hornets didn’t want to win from the Electricians,” the reporter for the Charlotte News wrote, then quickly added, “although such a statement is far from right.”

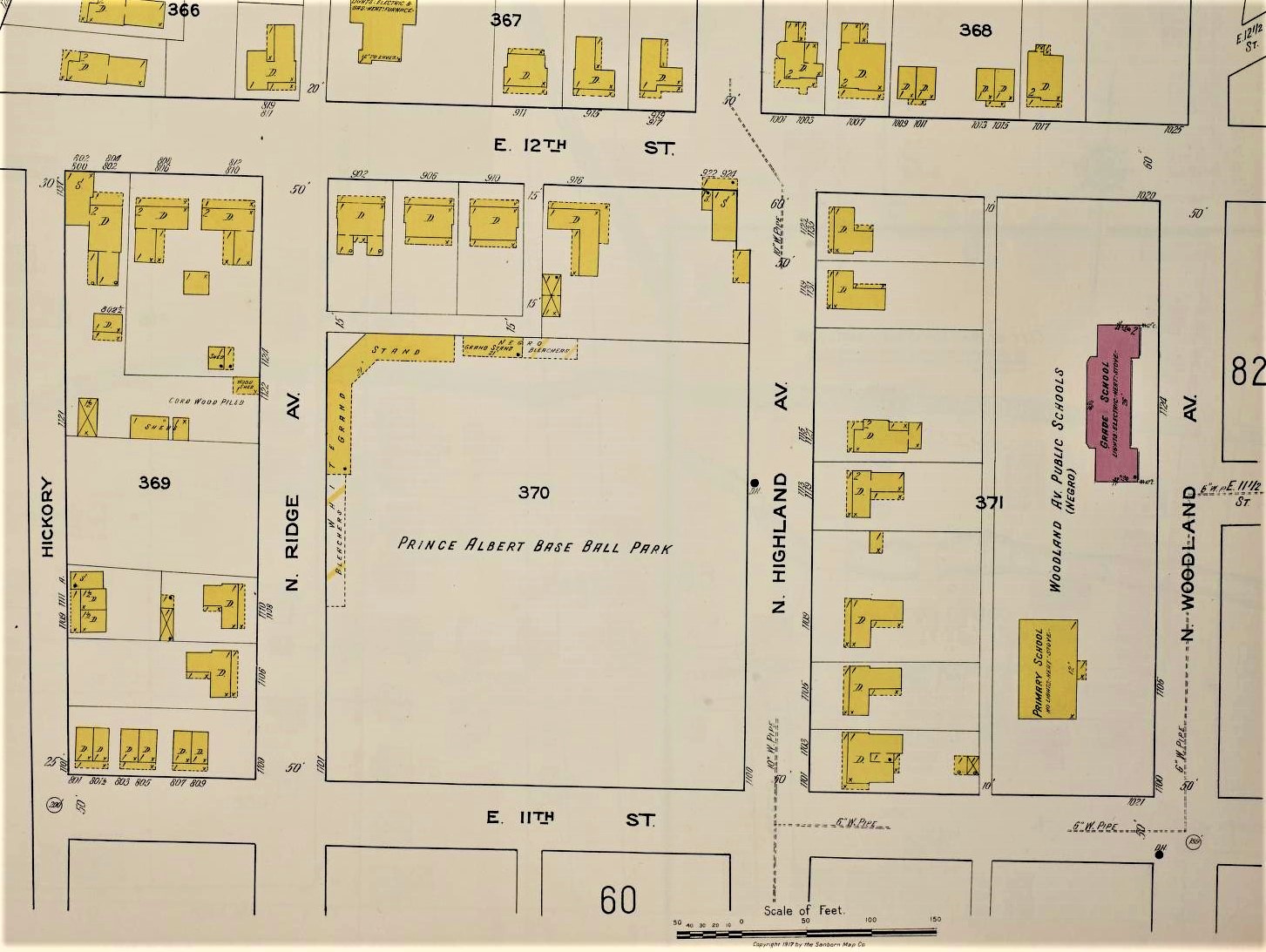

Winston-Salem’s Prince Albert Park. The small grandstand and bleachers on the third base side were for Black spectators. Sanborn Fire Insurance map, 1917.

Winston-Salem’s Prince Albert Park. The small grandstand and bleachers on the third base side were for Black spectators. Sanborn Fire Insurance map, 1917.

Since leaving the Hornets, Sheesley had pitched against his old team twice without major trouble. The peace ended on Wednesday, August 7, when the third-place Twins met the second-place Hornets in Winston-Salem’s Prince Albert Park. Sheesley got the start for the Twins, and High took the mound for the Hornets.

The first sign of trouble had arrived a few days before the game when Sheesley received a threatening letter from Charlotte manager Champ Osteen. “The local twirler has in his possession a letter from Osteen, the contents of which are declared to be of an intimidating nature,” the Twin-City Daily Sentinel reported.

The Greensboro News described the letter as “mentioning a few things that would be done to Sheesley in case ‘something happened.’”

The News did not specify the “something” in question. But Osteen was undoubtedly worried that Sheesley would blow the whistle on the Hornets’ habit of losing at convenient times. In the ensuing dustup, Charlotte’s 21-year-old left fielder, Harry Budson Weiser (known, of course, as “Bud”), became Osteen’s designated hitman.

Like most characters in this story, Weiser hailed from Pennsylvania: he was born, lived, and died in Shamokin. Weiser played semi-pro ball in Shamokin when Haddow – then known as Black – played for the town’s Central Pennsylvania League club. The two best ballplayers in a town of 20,000 likely crossed paths at some point.

Charlotte’s then-manager, Lave Cross, who probably observed the youngster while managing Shamokin’s Atlantic League team, signed Weiser in late 1910. He was with the Hornets for all of the 1911 and 1912 seasons.

The day before the August 7 game against Sheesley, Champ Osteen sold Weiser’s contract to the Class A Southern Association’s Atlanta Crackers for $1250. Weiser would stay with Charlotte through the end of the Carolina Association season, then report to Atlanta.

“It is said that Weiser remarked that he would ‘get’ Sheesley,” the Greensboro News recounted, “and it must be admitted that he did. That is, he tried to.”

Doc High held the Twins scoreless until the bottom of the fifth when he proved that his pitching ability was an ephemeral entity. Two walks and an error by shortstop Osteen loaded the bases. A third walk brought home a run to give the Twins a 1-0 lead.

Sheesley pitched well, shutting out Charlotte for seven innings. He perhaps derived too much delight in mastering his former teammates. The Hornets responded with jeers and insults. The Winston-Salem Journal said the Hornets “gave vent to their spleen and used every unsportsmanlike means to harass the local twirler.”

Real trouble arrived in the top of the eighth. George Bausewein (spelled Bauswein in the newspapers), a popular pitcher and outfielder, entered the game for Charlotte as a pinch hitter with two Hornets on base. Bausewein singled, bringing the two runners home and giving Charlotte a 2-1 lead.

The next batter hit into a sure double play, but Bausewein, barreling down from first, bowled over the Twins’ shortstop. It was an out-of-character move for Bausewein, who was known as a good-natured fellow.

Both benches emptied. The players stormed the field, followed by a squad of policemen who endeavored to keep the belligerents apart. Champ Osteen ran out waving a bat, but Sheesley stopped him. “Mr. Osteen rushed across the diamond, brandishing a bat,” the Winston-Salem Journal reported. “He was accosted by Sheesley, who doubtless merely complimented him on his courage in venturing forth with simply a small bat to defend himself.”

Osteen dropped the bat and assumed a pugilist’s pose facing Sheesley, but the cops intervened before any blows could fall.

After the Hornets were retired, Bausewein took Weiser’s place in left field, and Weiser moved to second base.

High and Malcomson helped their opponent bounce back in the bottom of the frame. With runners at first and second, the Twins attempted a double steal. Catcher Malcomson heaved the ball wildly, allowing the lead runner to score while the other advanced to third. High obligingly balked, the runner on third trotted home, and the Twins took a 3-2 lead.

While the players swapped positions between innings, Weiser dawdled on the diamond long enough for Sheesley to reach the mound and begin his warm-up tosses.

As Sheesley threw to catcher Bull Powell, Weiser stepped over to the mound and started talking. Sheesley waved him away and gestured for the umpire. When Weiser continued to jaw, Sheesley turned and landed a solid blow square on Weiser’s nose, knocking him to the ground. Players and policemen again swarmed the field.

As players and cops milled around the mound, High came up behind Sheesley and sucker-punched him with a roundhouse right to the eye. “High, the Charlotte pitcher, mustered up his courage and struck Sheesley on the side of the head,” the Charlotte News said.

Weiser, meanwhile, picked himself up and tried to get back into the fight. In the course of punching someone, he broke his right thumb.

The police restored order, and Special Officer Martin, a solid Winston-Salem man, arrested Weiser even though Sheesley had struck the first blow. Various players voiced “I’ll get you later” threats before the game continued.

Pitching with his eye swollen nearly shut, Sheesley blanked the Hornets and left the field with a 3-2 win.

That night, Twins catcher Bull Powell set out to settle the score with the man who had blindsided his pitcher.

Powell, twenty-nine years old, had been slogging around the low minors for eight seasons and knew how to handle himself. He was a big Texan, the son of a blacksmith. Powell had answered President McKinley’s call for volunteers to fight the Spanish when he was 15, served six months as a company drummer in San Antonio, and received an honorable discharge.

Powell may have been harboring a grudge against High for two years. In 1910, when High pitched a single game for the Augusta Tourists, he beaned Powell, who was playing for the Columbia Comers. According to the Columbia State, “High was a little up in the air (no joke) and mistaking Bull Powell’s rather conspicuous pate for the counting station, sent one straight to Bull’s head.”

Powell located Doc High in the dining room of the Hotel Zinzendorf. High jumped up and pulled out a Case knife. Powell wasn’t afraid of a punk with a pocketknife. He grabbed a fork from a nearby table and went after High.

Neither player was seriously injured in the ensuing brawl, but each left a few marks on the other. “The report that both of them got the worst of it will please almost everybody,” Julian Miller concluded, though one must consider that Powell, armed with a fork against High’s knife, was the moral victor.

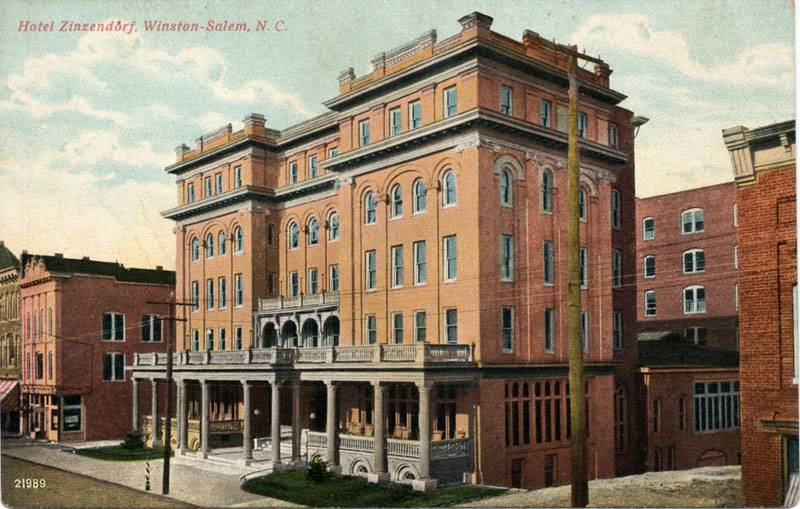

Winston-Salem’s Hotel Zinzendorf. The original Hotel Zinzendorf was destroyed by a fire on Thanksgiving Day, 1892. The new hotel, on Main Street, opened in 1906 and closed in 1970.

Winston-Salem’s Hotel Zinzendorf. The original Hotel Zinzendorf was destroyed by a fire on Thanksgiving Day, 1892. The new hotel, on Main Street, opened in 1906 and closed in 1970.

Weiser, Sheesley, High, and Powell appeared in court on Thursday morning, facing Judge Hastings, a former president of the Twins. Powell got away with a $10 fine while the others added $20 each to the municipal coffers. League President Wearn fined Sheesley and Weiser $15 each and suspended both players for one week.

Manager Champ Osteen escaped punishment. Word around the circuit was that Osteen had instigated the entire affair and that Weiser was following his skipper’s lead. But Wearn expressed no interest in investigating Osteen’s role in the affair or in getting to the bottom of the bad blood between Osteen and Sheesley. Wearn had to be aware that something shady was afoot in Charlotte. And whatever it was, he intended to keep it out of the newspapers.

When Wearn announced the suspensions of Sheesley and Weiser, a great howl went up in Winston-Salem. Sheesley represented a significant segment of the Twins’ pitching staff; his absence would significantly harm the Twins. But since Weiser was now out of action for the rest of the season with a broken thumb, his suspension would not incrementally harm the Hornets. Or so the thinking of the Twins’ fans went.

“What we want is that in case Charlotte should win the rag that they shall win it fair and square, and not by such tactics as are now being advocated,” the Twin-City Daily Sentinel complained. “The impression is growing that Mr. Wearn is too easily influenced by Charlotte interests for the good of the league.”

Faced with the protests, Wearn immediately lifted the suspensions pending “further investigation.” Wearn mulled the issue over during the weekend, then on Monday morning, August 12, he announced that the one-week suspensions had been re-instated and would begin immediately.

That afternoon, John Haddow, angered by his friend’s suspension at the hand of his club owner, let the game-throwing cat out of the bag.

The Hornets, with Bausewein twirling for the locals, took on the Twins in Wearn Field. For the Twins, Roy Radebaugh (spelled Radabaugh in the newspapers) stood on the mound with Bull Powell, now ten dollars lighter, behind the plate. Charlotte won, 6-5.

The Observer’s Julian Miller buried the lede, sinking the real story into his second paragraph:

“The Hornets paid a fancy and almost fatal price for the victory. They laid upon the alter of their ambitions the best third baseman that has ever cavorted at that corner in the history of the league, John Haddow, who may draw an indefinite suspension from manager Osteen for his conduct and abusive remarks made in the third inning. Manager Osteen benched the player just at the conclusion of an unpleasant episode during which Haddow lost his temper and made a quasi-confession that may mean his abandonment of organized baseball for an indefinite period.”

The Hornets jumped on Radebaugh for six runs in two innings. The Twins started back in the third. After scoring two runs, they had Bull Powell on first and first baseman Bill Schumaker on third with one out. Manager Charles Clancey called for a double steal.

Schumaker had no chance. He pulled up and retreated to third. Catcher Malcomson fired the ball to Haddow, who caught it for an easy tag and… dropped it.

Haddow’s error was devoid of deception. “Haddow dropped a throw which was too easy to talk about,” Julian Miller said. The Greensboro Daily News was more direct: “He very plainly dropped a thrown ball on purpose.”

With Schumaker now headed for home, Haddow picked up the ball and threw it against the grandstand.

Similar sequences had characterized Charlotte’s losses since Opening Day. But this time, with the larceny evident to everyone in Wearn Field, manager Champ Osteen, to Haddow’s left at shortstop, was obliged to speak up.

Osteen yelled something at Haddow, probably What the heck are you doing, trying to throw the game? But the newspapermen were more discrete in their descriptions of the exchange.

“Manager Osteen spoke to him about the play,” the Evening Chronicle reported. The Charlotte News said, “Osteen reprimanded Haddow.” And the Daily News said, “Osteen asked him the reasons for this error.”

The Evening Chronicle captured Haddow’s response: “I have beat you out of several games already and am going to beat you out of more.”

The conversation might have been swept under the rug except for the presence of umpire Scott Chestnut, who had run up the line from home and overhead Haddow’s confession. Osteen had no choice but to banish Haddow to the bench.

“Osteen very emphatically declared that the games thrown away by him (Haddow) in the future would be bush league games,” J.M. Broughton, sports editor of the Winston-Salem Journal, noted. Broughton then added a thus-far unreported motivation for Haddow’s behavior: “Haddow is said to have been sore on the local club since Sheesley left and joined the Twins, it being claimed that he tried to get his release at the same time.”

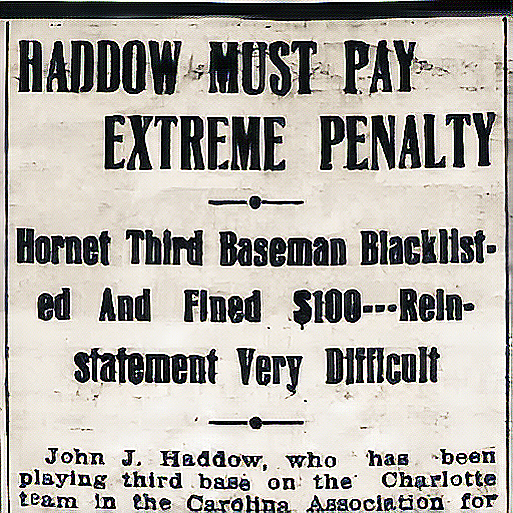

Haddow was slapped with a $100 fine – or $200 according to some reports – and given an indefinite suspension. Most assumed that Haddow would be permanently banned from professional baseball.

“Haddow left the club and could not be found to get his statement of the affair or what he intended to do about the case,” the Evening Chronicle reported. “It is presumed that Haddow will leave the city tonight, as all connections with the league have been severed.”

Report of Haddow’s suspension and fine. Charlotte Evening Chronicle, August 13, 1912.

Report of Haddow’s suspension and fine. Charlotte Evening Chronicle, August 13, 1912.

The fate of Haddow was greatly exaggerated. Osteen and the club had not decided on Haddow’s future. As Julian Miller explained the day after the game, “He [Osteen] said that he would not announce a definite decision until this morning, that under the circumstances, he might pass over the forgetfulness of the player who lost himself in a moment of anger. He is somewhat at a loss to know exactly what to do.”

Osteen had a genuine exploding stove on his hands. Haddow’s confession made every newspaper on the Piedmont Plateau; the situation could not be covered up. But Haddow was not the only Hornet involved in the game-throwing. Sheesley was almost certainly involved. High sometimes made no pretense of trying to lose. Agnew, Malcomson, Boyne, Bentley, and Osteen himself had multiple suspicious plays to their credit.

Haddow might blow the whistle on the entire enterprise. He would have no reason to keep his mouth shut if he received a permanent ban from professional baseball. Even if Osteen could not be directly implicated, the shipwreck had occurred on Osteen’s watch. It would be the end of Osteen’s career as a manager.

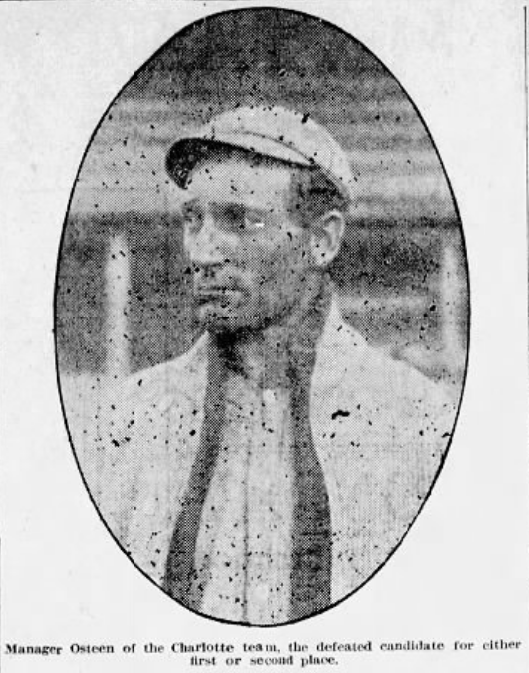

Charlotte player-manager James “Champ” Osteen. Charlotte Daily Observer, September 1, 1912.

Charlotte player-manager James “Champ” Osteen. Charlotte Daily Observer, September 1, 1912.

But the events had also happened on J.H. Wearn’s watch. As the president of both the Charlotte Hornets and the Carolina Association, Wearn was doubly responsible for allowing any wrongdoing on the field to persist through an entire season. And, perhaps more importantly, the Hornets were in the thick of a pennant race, just a few games behind the league-leading Anderson Electricians. They needed their starting third baseman.

League President Wearn once again acted in the best interests of Hornets President Wearn.

On Wednesday morning, August 14, Haddow met with Wearn and the directors of the Charlotte Base Ball Club. According to the Evening Chronicle, “He explained that what was said was done on the spur of the moment and that he was angry at the time. He explained that what he meant by the words he had used was that any ball player would cause a game to be lost by an error that could not be helped, and that he was liable to make another error during the season that would mean a lost game to Charlotte. He was thoroughly penitent for the act and seemed to be sincere in what he had said and apparently gave a reasonable explanation of the whole affair.”

Left unexplained was the fact that Haddow intentionally dropped Malcomson’s throw, then intentionally threw the ball against the grandstand, and that his intent was obvious to everyone watching the game.

No matter: Wearn and the directors decided that Haddow had not been throwing games despite his initial confession to the contrary. Wearn re-instated Haddow, lifted his fine, and sent his third baseman out onto Wearn Field that afternoon to face the Winston-Salem Twins in the series’ final game.

The Twins jumped on Charlotte starting pitcher Manning Smith for three runs in the first inning. Rain began falling in the fourth inning; by the fifth, with the score still 3-0, it was coming down in buckets. Pools formed in the players’ footsteps, but umpire Scott Chestnut insisted that play proceed.

With one out, Winston-Salem’s Bill Schumaker – the player that Haddow had allowed to score two days before – doubled. Bull Powell sent a roller to Johnny Agnew, who couldn’t extract the ball from the muck. Schumaker rounded third and headed home. He was halfway there when catcher Malcomson took the throw from Agnew. Schumaker retreated towards third as Malcomson pegged the ball to Haddow… who dropped it, allowing Schumaker to score.

It was a stunning re-enactment of the play that nearly blacklisted Haddow. But this time, Haddow feared not the consequences. By lifting Haddow’s suspension and fine, J.H. Wearn gave Haddow and the Hornets permission to throw all the games they wanted. Haddow’s latest error was a giant middle finger to everyone who predicted he would be permanently banned from professional baseball.

The Hornets came back in the bottom of the fifth and scored three runs. The game ended in a torrential rain after six innings, with the Twins leading 4-3. Haddow’s “error” provided the winning run.

The second-place Hornets, now 4 ½ games behind the league-leading Anderson Electricians, journeyed to Anderson the next day for a critical four-game series. Doc High started the first game and, once again, showed little interest in winning. He sulked, pouted, criticized the umpire, and gave up six runs in less than five innings. The ump finally chased High to the bench, in the words of Julian Miller, “on account of crabbing.”

The Hornets lost three out of four games in Anderson. They were still in second place but led the third-place Twins by only a half-game.

The Hornets met the Spartanburg Red Sox in Wearn Field on Monday, August 19. For this critical game, Osteen again sent Doc High to the hill in front of a motley clot of 425 fans. Having survived Haddow’s public admission of throwing games completely sans punishment, the Hornets no longer tried to hide their intentions.

Headline in the Charlotte Daily Observer, August 20, 1912.

Headline in the Charlotte Daily Observer, August 20, 1912.

After watching the spectacle, Julian Miller let fly his disgust to the probable amusement of the Linotype operator, who had seen several such young men in his day and would see several more before hanging up his cap.

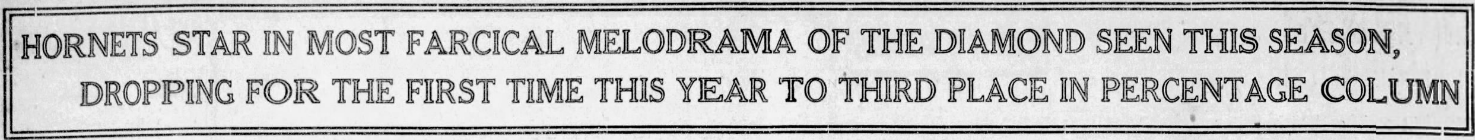

Under the headline HORNETS STAR IN MOST FARCICAL MELODRAMA OF THE DIAMOND SEEN THIS SEASON, DROPPING FOR THE FIRST TIME THIS YEAR TO THIRD PLACE IN PERCENTAGE COLUMN, Miller wrote:

“Weird pitching, rotten playing and rank stupidity at every turn enabled the Spartans to tuck away the first game of the series with the Hornets by the score of 12 and 5. Prominently punk and spectacularly sleepy were the locals during the greater part of perhaps the worst exhibition of baseball ever seen under the guise of professionalism here. Poor managerial ability oozed itself through the seeping filth and foulness and great gatherings of garbage strewn across the field.”

The Hornets played with intentional indifference. Dinky grounders dribbled between infielders for hits. Balls fielded cleanly were held until every runner was safe. Hits beyond the diamond required relays to reach a base, the Hornet outfielders having universally developed sore arms.

Despite the rottenness, the sixth inning opened with the Hornets leading 3-2. Spartanburg third baseman Jack Corbett led off with a fly in front of the plate. High and catcher Malcomson allowed the ball to drop between them as Corbett reached first. He immediately stole second, then third.

High responded by drilling Spartanburg right fielder Whiskers Weir. He next sent a fastball into the back of center fielder Ed Doak’s head, knocking him unconscious. Players carried Doak from the field under the care of two physicians as a pinch runner trotted from the bench to load the bases. A grounder forced Corbett at the plate, but four straight hits brought in an equal number of runs.

The Hornets returned with two runs in the seventh inning as High held steady until the ninth. But in that final frame, High surrendered all pretense of playing to win. “In the ninth he became sulky and seemed to be trying to hand the visitors tallies,” the Charlotte News reported.

“The Spartans made a slaughter of it in the ninth inning,” J.M. Broughton of the Winston-Salem Journal wrote. “High merely lobbed the ball over and then laughed as the outfielders chased the fence smashers that the Spartan sluggers pounded out. Four bases on balls, three hits, three steals and two errors netted the Spartans six runs in the frightful period.”

The game mercifully ended with Spartanburg leading 12-5. Summarizing High’s pitching performance, young Miller pulled out all the stops and referenced an old fiddle tune called “Hell Broke Loose in Georgia” that would not be committed to wax for another thirteen seasons:

“The disaster that is said to have broken loose in Georgia fell spattering across the bunch in the sixth inning when High’s control plumed its pinions and departed these coasts, being even at this moment a refugee from justice. Although traces of its tracks were seen in the seventh and eighth innings, the demon of wildness, amid the shrieks and moans and unutterable protests of the spectators, left dashing in the ninth and has been since regarded as beyond the range of apprehension.”

Meanwhile, Jack Sheesley was mowing down the Anderson Electricians in Winston-Salem, striking out 11 and allowing only four hits on the way to a 5-1 win. The day ended with the Winston-Salem Twins in second place and the Hornets relegated to third.

The drop in the standings sucked the life out of the Hornets, as well as out of the Charlotte fans and sportswriters. The following day, Julian Miller made the one-mile journey to Wearn Field from the Observer’s office at 32 South Tryon and sweated in 94-degree heat as he took notes on a game that thoroughly disinterested him: “The score was 6 to 1. The game was listless and dull. The locals were helpless and infantile. The Spartans were at the heighth of playing form. The crowd was critical and unkind. The umpiring was not better than ordinary. The weather was hot as blue blazes. There was nothing at all redeeming about the afternoon.”

The Hornets completed their 1912 season on Tuesday, September 2, with a doubleheader against the pennant-winning Anderson Electricians in Wearn Field. Doc High started the morning game. He and Haddow tried – but failed – to hand the game to the visitors.

In the first inning, High walked two and drilled another but gave up no runs. In the second, successive errors by Haddow placed runners at second and third. A single by Anderson pitcher Paul Fittery brought them home. High repeated his first-inning antics by walking two and drilling a batter, bringing Fittery home. After the third run, Osteen yanked High for the final time.

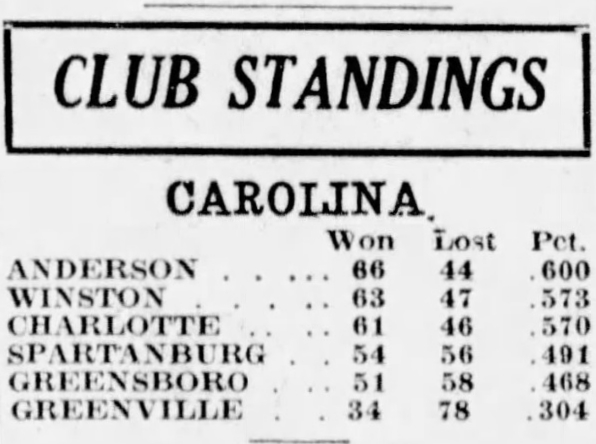

After High’s departure, the Hornets came back and took the morning game 8-7, then won the afternoon game 6-5. In the Carolina League’s final standings, Charlotte stood in third place, 3 ½ games behind the pennant-winning Anderson Electricians and a mere half-game behind the second-place Winston-Salem Twins.

Final Carolina Association standings. Charlotte Daily Observer, September 3, 1912.

Final Carolina Association standings. Charlotte Daily Observer, September 3, 1912.

So…

Were the Charlotte Hornets losing intentionally in 1912? Or is the researcher exhuming selected facts and assembling them into a pre-conceived narrative?

The first question cannot be answered with certainty when looking back at the 1912 season from 111 years down the road. I believe the Charlotte Hornets intentionally lost many games in 1912, enough to keep them from winning the pennant.

To answer the second question…

I started with Haddow’s confession, accepted it at face value, and worked backward, looking for evidence that Haddow had thrown games. Encountering the trouble with Sheesley and Osteen’s threatening letter, I initially assumed that Sheesley had been a victim, with the Hornets behind him conspiring to lose his games. But after reading the game summaries and discovering the friendship between Sheesley and Haddow, I decided that Sheesley had been a willing participant in the affair, possibly its ringleader.

But, considering the baseball environment in which the events took place, the errors, misplays, lazy efforts, and poor pitching that I assumed were signs of game-throwing could be passed off as typical Class D play by Class D players on Class D diamonds. At the end of the streetcar line, the only direct evidence I have for game-throwing is Haddow’s confession, which he immediately retracted.

Along the way, I encountered Doc High. High is more difficult to evaluate. He was a great pitcher in the first half of the season. In July and August, we find multiple instances of High appearing to go AWOL while still on the mound. High’s most egregious farces took place after Sheesley departed. But were High’s actions a continuation of a Sheesley-Haddow game-throwing scheme? Or did the youngster’s arm give out after the first two months of the season? Was High emotionally unstable? Maybe.

And why did manager Champ Osteen continue giving High the ball? Most Carolina Association teams carried three or four pitchers on their roster. In July and August, the Hornets carried five. There was no reason for Osteen to continue sending High to the mound unless he was happy with the resulting losses.

Finally, if we accept that the Hornets were losing intentionally, WHY were they doing it?

Losing intentionally – or the accusation of doing so – was fairly common in the minor leagues back in the day.

The most frequently-voiced accusations were those heard near the end of nearly every season as teams closed in on the league’s pennant. A sportswriter would accuse a team of losing intentionally to benefit one team and hinder another.

In 1916, the North Carolina State League played a split season: basically, two seasons played back-to-back. A best-of-seven playoff series would determine the pennant winner if different teams won each half-season.

The Asheville Tourists, led by player-manager Jack Corbett, won the first half-season. Corbett displayed little interest in winning the second half-season, selling off many of his best players.

The Winston-Salem Journal accused Corbett of trying to lose or at least not trying to win. The Journal reasoned that Corbett and the Tourists wanted the extra revenue they would earn in a playoff series. The Tourists would make more money if they lost the second half-season.

Specifically, the Journal said, Corbett wanted the Charlotte Hornets to win the second half-season. Charlotte was a larger market, with more rabid fans than, for instance, Winston-Salem. More fans meant a larger split of the gate.

Corbett announced that he would sue the Winston-Salem Journal for libel. Nothing came of Corbett’s suit. Corbett later habitually sued people and institutions, including major league baseball, minor league baseball, and the National Football League.

Players sometimes performed poorly to extract an unconditional release from their contract, as Sheesley did in his last game with the 1912 Hornets. But Sheesley often pitched well, and his losses were often by the narrowest of margins. He wasn’t bad enough to warrant an unconditional release from the Hornets until his final game.

It’s possible that Sheesley, feeling underpaid and wronged, lost intentionally to exact revenge on the Hornets. He didn’t need to lose every game; he needed to lose only enough to cost Charlotte the pennant.

Haddow and Agnew would likely have followed whatever scheme Sheesley cooked up. But the pattern of errors and misplays suggests that the scheme extended beyond Sheesley, Haddow, and Agnew to Osteen, High, Malcomson, Bentley, and Boyne, and included bit players like Wofford, Weiser, and Hillix. If that many players were involved, then a lot of money was being passed around, an amount that only professional gamblers could supply. Of course, when players make $100 a month, “a lot of money” can be a relatively small amount.

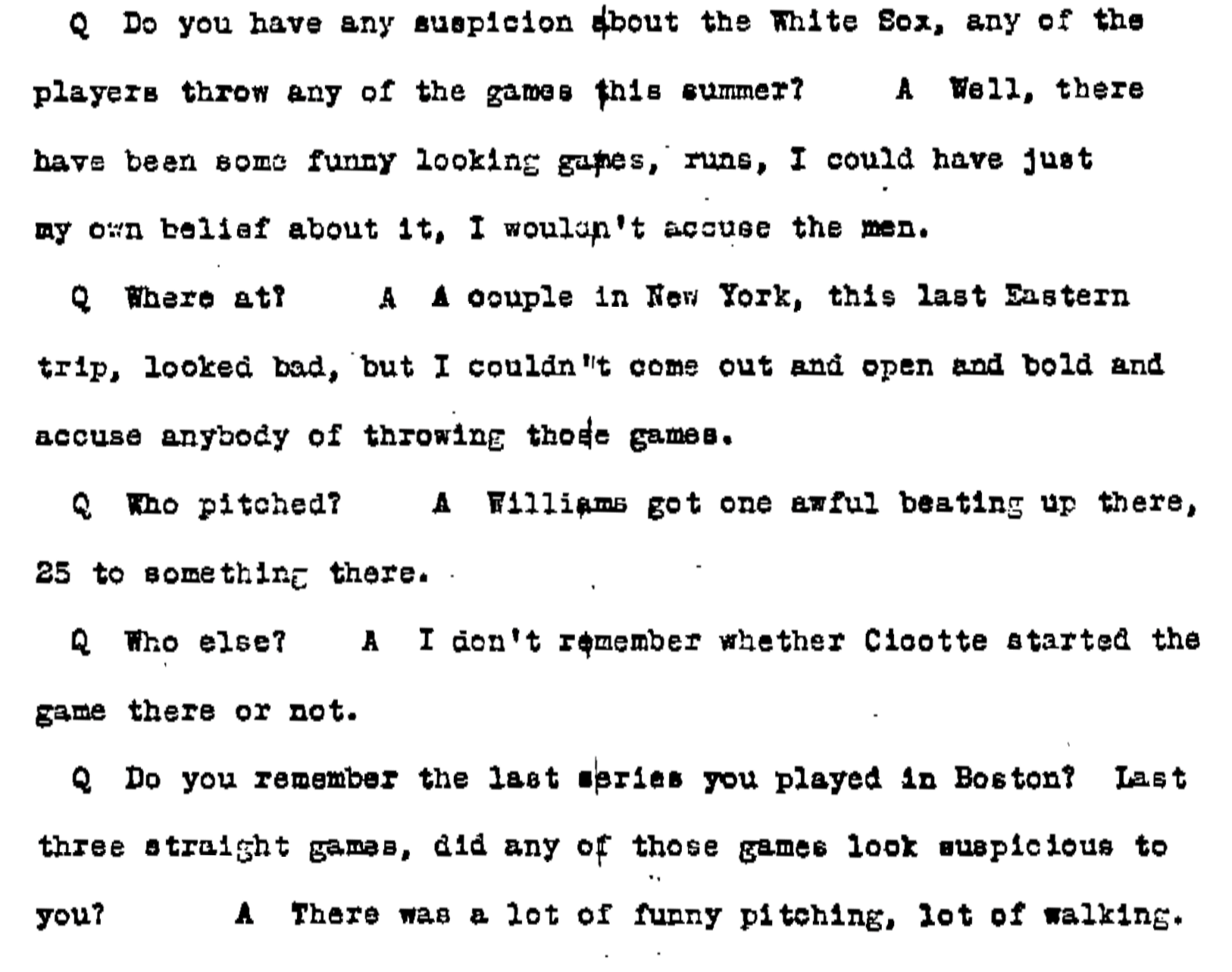

Gambling on baseball games was a common endeavor in those days. Fans would gather in grandstands across the country, even in the most dilapidated minor league ballpark, and bet on anything from the game’s winner down to the result of the next pitch. When major league owners cracked down on the practice, they noticed a drop-off in attendance as the gamblers moved from the ballparks to cigar stores, billiard halls, and saloons where they gambled on game results from a Western Union ticker.