Allandale Field – Asheville’s Rough Hillside Mountain Diamond

The Asheville Baseball Club has bounced in, out, and around the North Carolina town for over 130 years, perpetually seeking a home within an ever-evolving urban landscape.

The Asheville Baseball Club has bounced in, out, and around the North Carolina town for over 130 years, perpetually seeking a home within an ever-evolving urban landscape.

In 1892, the club’s ballpark was off Depot Street on a lot south of the Glen Rock Hotel. The following season, playing as the Invincible Highlanders, the team scratched out a diamond inside the half-mile oval of Carrier’s Racetrack.

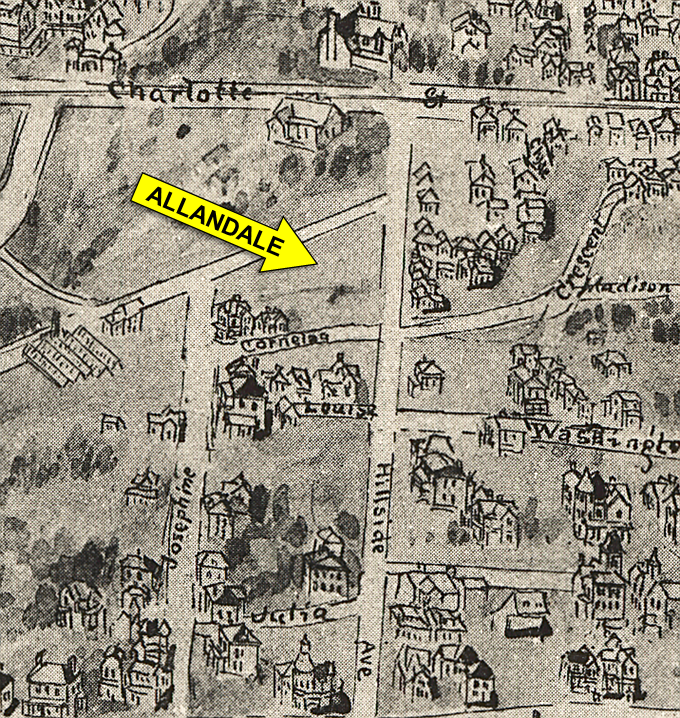

On March 27, 1894, the Asheville Baseball Club announced it had leased the property that would become its new baseball home: Allandale Field. The pasture in northeast Asheville, owned by the heirs of David Murdoch, was located “on the north side of Hillside Street, a short distance west of Charlotte Street.”

The southeast corner of the property was “about a minute’s walk from the street cars” that ran up Charlotte.

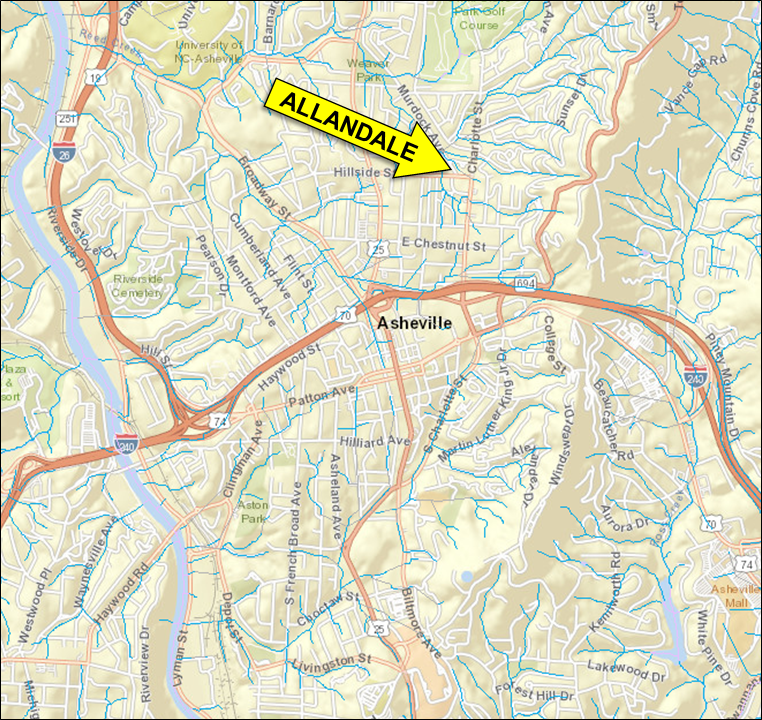

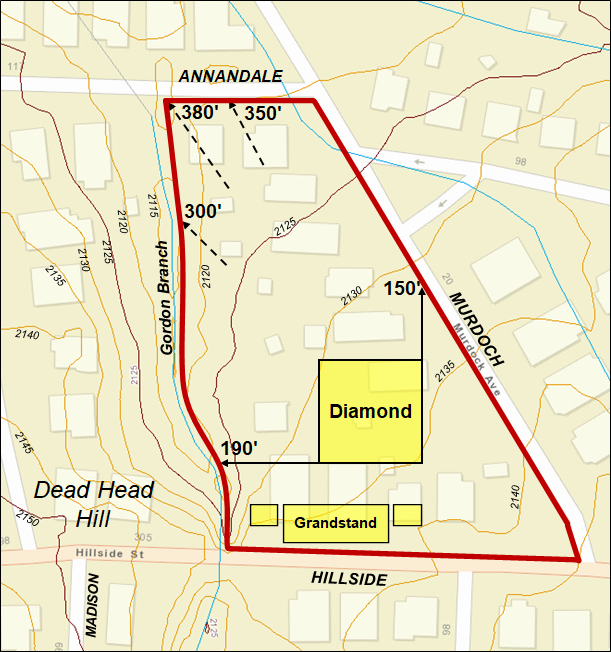

Location of Allandale Field in Asheville, North Carolina.

Location of Allandale Field in Asheville, North Carolina.

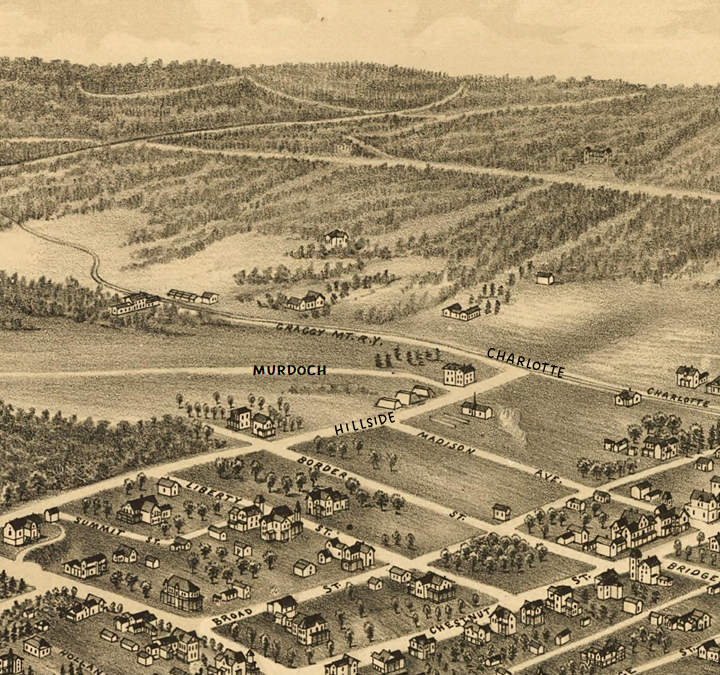

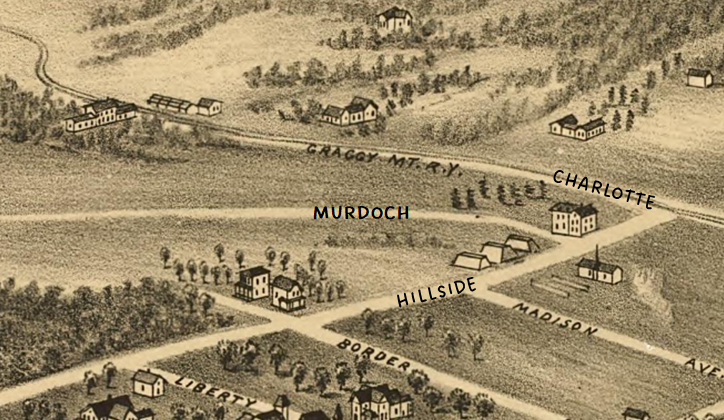

An 1891 panoramic sketch of Asheville shows an inviting slice of farmland on Hillside, bordered on the northeast by the primordial Murdoch Avenue and occupied by a few hay sheds.

Perspective map of Asheville published by Ruger and Stone, 1891. Not drawn to scale. Library of Congress.

Perspective map of Asheville published by Ruger and Stone, 1891. Not drawn to scale. Library of Congress.

The field was known as Allandale before being leased by the baseball club. “The name has long attached to the grounds as the domain of the Murdochs and will aptly serve the purpose of the present lessees,” the Asheville Citizen told its readers.

David Murdoch, who died of consumption in 1891 at age 48, was a native of Ayrshire, Scotland. His farm was known as Annandale (though in his will, he referred to it as “the Jarrett Place”).

Today the likely location of Allandale is bounded by Hillside Street, Murdoch Avenue, Annandale Avenue (then known as Josephine Street), and Gordon Branch, the modern name for the little stream that bisects the property between Murdoch and Cornelia Street.

Topographic map showing present-day elevations above sea level, possible location of the Allandale diamond and grandstand, and distances from home plate to the fence. Map created using the Buncombe County Geographic Information System, 2023.

Topographic map showing present-day elevations above sea level, possible location of the Allandale diamond and grandstand, and distances from home plate to the fence. Map created using the Buncombe County Geographic Information System, 2023.

Locating an ancient site on a modern map can be risky: Hillside and Murdoch were unpaved as late as 1913 and have undoubtedly moved around over the years. Construction, grading, and a century of erosion may have altered the lay of the land. But the characteristics of the current terrain fit the descriptions of the ballpark recorded back in the day.

The diamond was probably positioned in the tract’s southern half, where the widely-spaced contours of today’s topographic map indicate a flattening of the field.

“The batting direction will be northwesterly, giving home run hitters something like 350 feet of field before ‘it’s over the fence,’” the Citizen reported, indicating that home plate lay to the southeast. The 350-foot home run length matches the distance from the conjectured home plate to Annandale Avenue. By this estimate, the right foul line ran north; the left line ran west.

The distances down the lines as measured on the modern map, 150 feet to right and 190 feet to left, seem improbably close, especially in right field. At these distances, any ball that went over the fence down a foul line should have counted as a double: after 1892, a ball hit over a fence less than 235 feet from the plate was good for two bases.

It’s possible that Murdoch Avenue – then only a farm road – curved farther to the north, allowing for a deeper fence in right. But the left and right field fences were, at any rate, very close to the plate. In an age when over-the-fence homers were rare, accounts of the games tell of balls flying over Allandale’s fences at a good clip.

The ground of Allandale Field sloped away from home plate, with the outfield being noticeably lower than the infield. The current topographic map suggests an incredible 20 feet of drop between home plate and deep center field.

The playing field at Knoxville had the opposite problem. Observing a game there, a reporter for the Citizen noted, “The diamond here differs from the Allandale diamond in that the ground slopes toward home and third.”

Visitors maintained that the slope gave Asheville an unfair advantage. After his team lost a pair of games at Allandale, the manager of the High Point club complained, “The two games recently lost at Asheville should not be considered in the light of an overwhelming defeat, for the reason that the games were played on a hill side, where it was impossible for any one to play good ball, except those who had become accustomed to this particular ground.”

Another observer said, “No team can beat Asheville on her rough hillside mountain diamond.”

In an 1895 game, a passed ball on the third strike allowed the batter to go all the way around to third base. He was prevented from scoring when the left fielder “ran up from left field to cover the plate,” indicating the field’s slope and the short distance from left field to home.

The topography contributed to the number of home runs: batters were hitting downhill, requiring less loft to clear the fence.

A significant amount of water must have accumulated in the low ground along the center field fence. The Citizen described a long hit in 1894: “The fence was banged, and a man on his hands and knees at the spring got up and left the spot in a hurry.”

Weeds grew thick in the low ground. First baseman Pleasant McClung said of the growth in center field, “It ought to be plowed up and sawed into postholes.”

During an 1896 game, “the center fielder in going after a long fly did the frog act and was lost to view in the tall weeds.” He may have fallen into the branch.

The work of turning the old pasture into a ballpark commenced right after the lease was signed.

Frank Corpening, who had the contract to grade Asheville’s streets, brought in his big six-horse road scraper and smoothed out the diamond area, removing and redistributing several inches of dirt. Corpening then used a steamroller to flatten the field.

E.B. Lewis, principal of the Montford Avenue School, laid out the exact positions of the bases and foul lines.

Lewis’s work included “setting the pitcher’s plate.” The pitching slab was a recent innovation. Before 1893, pitchers worked from a 4-foot-wide box whose front line was only 50 feet from the batter. Under the new rule, the pitcher toed a slab placed 60-feet-6-inches from home.

The slab Principal Lewis installed was, apparently, an actual slab of stone laid atop a folded-up newspaper. In the near-Biblical words of the Citizen, “When he dug the hole for placing the stone there a copy of THE CITIZEN was put beneath the stone to serve as a cushion and as a root for Asheville wins.”

In the screenwriter’s imagination, Principal Lewis obtains the slab, cut to specification out of good Carolina granite, from W.O. Wolfe, the father of novelist Thomas Wolfe, who sold monuments and tombstones from his shop on Asheville’s Court Square. And who’s to say it didn’t happen that way?

Advertisement in the Asheville Citizen, February 21, 1894.

Advertisement in the Asheville Citizen, February 21, 1894.

The pitcher’s mound was not yet in universal use, and many ballfields did not have a mound until well into the next century. The accounts of 1894 do not mention a mound, and Allandale likely did not have one, at least during its initial season.

A covered wooden grandstand, flanked on the left and right by uncovered bleachers, was erected in the southwestern corner of the property, probably along the left foul line. The stands could hold 1000 spectators.

Spaces under the grandstand were enclosed to create a “dressing room” for the players and a refreshment stand that served iced lemonade. During heavy rains, both rooms became shelters for the soggy fans.

A large chalkboard, probably on the diamond’s first base side, displayed the runs scored in each inning. A desk for an official scorer completed the outfit.

Allandale was surrounded by a wooden fence on which local merchants were invited to purchase advertising space. A sign on the outfield fence for Thad Thrash’s Crystal Palace, a department store specializing in China and glassware, featured a large circle. Any batter lining a ball into the circle received five dollars.

The fences in foul territory were topped by netting, the Citizen explained, “To avoid delays from lost balls.”

A general admission gate occupied the southeast corner of the property.

Initial constriction required less than a month. J.M. Westall, a prolific Asheville builder, inspected the grandstand and bleachers on April 26 and declared the structures “perfectly safe.”

Westall was a brother of Julia Elizabeth Wolfe, the mother of Thomas Wolfe. He was represented in Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel by Will Pentland, “whose business hours were spent chiefly in figuring upon a dirty envelope with a stub of a pencil, paring reflectively his stubby nails, or punning endlessly with a birdlike wink and nod.”

Despite Westall’s approval, Allandale’s grandstand was probably not a solidly-built structure. The wooden ballyards of that era were not built to last and began to deteriorate as soon as the last nail was hammered in.

Allandale hosted its first action on Saturday, April 28, 1894, when the Asheville Baseball Club, now known as the Moonshiners, took on Weaverville. The players ran onto the field in red and white uniforms, a fact revealed in an advertisement for W.M. Hill’s meat company: “Good Signs, Red and White – Colors of the Asheville Baseball Club and of our meat.”

Advertisement in the Asheville Citizen, June 13, 1894.

Advertisement in the Asheville Citizen, June 13, 1894.

The spectators at the first game were mostly hardcore fans, known as “33rd-degree cranks.”

“Some of the cranks were there, but the game was not considered vital enough to bring them all out,” the Citizen said. The problem never resolved itself. The teams that played in Allandale had a core of ardent fans, but attendance at the games was never enough to keep the club afloat.

The cranks on hand saw the Moonshiners win 19-15, a fairly typical score for those days. When the final out was tallied, it was raining, the sun was setting, and the current on the streetcar line had been cut. The cranks who had coughed up their 25 cents to support the club were punished for their good intentions by being forced to take a long, dark, wet walk home.

Allandale’s initial game revealed a problem the club’s directors may not have anticipated: the large number of non-paying spectators who would, in the words of the Citizen, “look on the game deadhead over the fence.”

The ground rose sharply on the far side of the branch. Just across from the north end of Madison, the elevation stood high enough to see over the left field fence. The rise became known as Dead Head Hill, honoring the crowd that gathered there to watch the games. On some afternoons, the number of freeloaders on the hill exceeded the number of paying customers.

The ball club posted “no trespassing” signs on the hill, but the deadheads ignored them.

In the spring of 1894, an army of 500 men left unemployed by the Panic of 1893 marched from Ohio to Washington, DC, to protest the government’s lack of response to the working man’s plight. Led by Jacob Coxey, the marchers were known as “Coxey’s Army.”

After the Moonshiners played a pair of uninspiring games against Salisbury, the Citizen received a card signed Coxey’s Army on the Hill: “Will you please ask the baseball club to have us a grand stand placed on our hill and have the games more interesting than the last two with Salisbury or we will not attend again.”

The club responded by stretching a canvas sheet above the left field fence to block the view.

Greenville’s ball club arrived in Asheville on Thursday, May 31, for the first important three-game series of the season.

The Moonshiners lost the first game 19-5 while playing in a strong north wind “that every minute cast dust in the players’ eyes.” In the eighth inning, Darby, Asheville’s shortstop, “knocked a ball way over right field fence right in the teeth of the blast.” Greenville’s batters responded by sending two balls over the left field fence.

In the next morning’s Citizen, Ray’s Bookstore (telephone 194) used Darby’s home run to sell flypaper: “Darby Knocked a Fly Out– Side the Allandale fence. That’s one way of knocking flies out. A better and surer is to use Tanglefoot Fly paper. It knocks out more flies than any thing made. We keep it.”

Advertisement in the Asheville Citizen, June 1, 1894.

Advertisement in the Asheville Citizen, June 1, 1894.

A large crowd of cranks turned up for Friday’s game. The Asheville Street Railway handled the influx “in good shape,” running cars up from Court Square every fifteen minutes.

Many fans arrived by carriage, exhausting the available space outside the grounds. The extras were herded inside the fence into deep right field, where they interfered with the fielders several times.

Our man at the Citizen went hyperbolic as Asheville won, 8-5: “If Greenville expected to resolve itself into a whirlwind and sweep the team off they soon realized that their stick of chewing gum was more than they could masticate.” He claimed that the cheering at Allandale could be heard a mile away.

Eight hundred cranks witnessed Saturday’s rubber match. They got their quarter’s worth as the teams played for three hours and completed 13 innings before the game was called for darkness with the score tied 12-12. The teams combined for 14 stolen bases, including four by Asheville pitcher George Stephens who contributed a “long hit to the spring that landed the pitcher on third.”

The Greenville series revealed the cranks’ worst habits: drinking and gambling.

After the final game, the Citizen said, “If people will drink whiskey, go to the games and misbehave themselves, the club ought to put them out.” The newspaper also called out the gamblers, especially deriding the local cranks who had put their money on Greenville.

Later in the season, the Citizen again took on the bettors: “The management of the Asheville Baseball club hope earnestly that betting at the grounds may be no more seen. This evil, which has been commented on by THE CITIZEN heretofore, is affecting the game seriously; so much so, that many of the most desirable patrons, among whom are a number of ladies and several ministers, have decided that they must forego the pleasure of seeing the good play because of so unpleasant surroundings.”

Swearing and smoking drove other desirable patrons from the grounds.

The Asheville Baseball Club operated as an independent outfit in 1894, taking on teams from Knoxville, Charlotte, Arden, Avery’s Creek, Chattanooga, Spartanburg, and Augusta. The Moonshiners’ season ended on Monday, September 3, with a 3-7 loss to Knoxville in Allandale. A two-game series against Knoxville had been on the books, but the attendance at the opening game was too poor to justify another.

In the fall, Allandale became a football field. Notable 1894 games included a match between Sewanee and the University of North Carolina (taken by UNC, 36-4) and a big Thanksgiving Day game pitting Bingham against Knoxville’s Baker-Himel School (Bingham won, 12-0).

Allandale received a few enhancements the following year.

The covered grandstand shadowed the eastern bleachers, but the western bleachers took the full force of the afternoon sun. In 1895, the western bleachers were given a canvas covering described as “very attractive.”

During Allandale’s initial season, games had been scheduled to begin at 4:30, but the first pitch was never thrown on time. The official start time was moved back to 5 o’clock in 1895 to accommodate those who worked late or were coming in from beyond the city.

A new item was added to the refreshment stand: spectators who wished to “put the players in a light never heard before” were invited to rent a phantom camera. The devices were small three-cornered boxes with two eye holes that distorted the view like a funhouse mirror. After phantom cameras became a minor craze, a cynical New York writer said, “They can be carried in the pocket and afford infinite amusement to people who are easily pleased.”

Progress was made in the war against the deadheads. The ball club leased the grounds outside the park, giving the “No Trespassing” signs better legal leverage.

Decreasing the non-paying customer base did not bring more quarters to the turnstile. Attendance dropped, and the Asheville Baseball Club, already in debt after the construction of Allandale, could not afford to put a team on the field.

The club attempted to raise funds with a minstrel show at the Grand Opera House, a lawn party (which gathered $35.50 from Asheville’s society ladies), and by sponsoring an excursion train to a game in Waynesville. But by the summer of 1895, the writing was on the clubhouse wall and the Asheville Baseball Club disbanded due to a “lack of patronage.”

The Moonshiner’s played their last game of 1895 at Allandale on August 14, taking on a team from Shelby. After five innings, with Asheville leading 13-1, the Shelby players simply walked out the gate without saying “Goodbye.” It was a fitting end to a disappointing season.

On a Saturday afternoon in the spring of 1896, an enterprising teenager named Charles Massagee combed through the Allandale outfield and gathered 25 four-leaf clovers and 13 of the five-leaf variety. Whatever good luck Massagee found did not transfer to the Asheville Baseball Club, whose fortunes continued to roll downhill.

“Out at Allandale there is an air of depression – a condition that is foster brother to despair, and the spring-coated blades of grass are bowed with fear that this year they will have not the opportunity to be trampled by the spiked foot-harness of some loving Moonshiner,” the Citizen lamented.

A pair of baseball men in Knoxville arranged to take over Allandale’s lease and put a team called the Vanderbilts on the field, but the plans never materialized. In April, the Asheville Baseball Club sold all of its equipment to the YMCA. The organization took over payments on the Allandale lease and promised to give Asheville “the best team the city could afford.”

The YMCA fielded a team that kept the cranks satisfied, though the quality of ball was less than what the Moonshiners had provided.

Allandale’s rickety construction and semi-rural location made the ballpark an inviting target for scavengers searching for a ready supply of wood to burn during the cold winter months. For some reason, the grandstand’s roof became a prime source of planks.

When the YMCA team took the field, much of the grandstand’s roof had gone missing. Repairs were not completed until mid-May.

Joy returned to the cranks’ hearts in March of 1897. A new Asheville Baseball Club announced plans to resurrect the Moonshiners and enter the Southeastern League. The directors budgeted $50 to repair Allandale Field, with labor provided by local fire companies.

The road scrapers returned, smoothing off the infield and packing the spoil in left field.

A large number of planks had again disappeared from the grandstand’s roof during the winter, along with 150 feet of the fence. Another 300 feet of fencing had fallen down.

The firemen repaired the fence and grandstand with mixed results. The fence on the east side of the grandstand was replaced with 14-foot planks. But a sloppy job on the grandstand’s roof left several large openings. On clear days, the sun shone through the gaps and roasted those caught in the rays. During rains, the patrons moved about trying to find dry harbors within the cascade.

The general admission gate was relocated to a position nearer the grandstand. Finally, the firemen added “a place set apart as a reporters’ stand” – probably a rudimentary press box.

In an April exhibition game, the Moonshiners trounced the boys of Bingham School 32-1. The Citizen’s reporter, perhaps elated equally by the return of professional baseball and by the use of his new desk, ran completely off the rails, penning a lede worthy of the sportswriters’ hall of fame:

“The Bingham boys took a shy at the Moonshiners at Allandale Monday afternoon and got as hard a fall as the man did who dropped off his barn with a bundle of shingles in his arms. The Ashevilles played all over the opponents, and hits were as plentiful as whereases at a Populist convention.”

The return of the Moonshiners brought a return of the army on Dead Head Hill. After one game, someone counted 103 deadheads walking home down Madison Avenue. “It is a pity that the fence on the left of the grand stand cannot be raised about 40 feet. Then the deadbeats would be compelled to seek other quarters – or give the gatekeeper their quarters,” our man at the Citizen punned. Instead, the club once again stretched a canvas above the left field fence.

The Southeastern League, an unclassified circuit, opened the season with teams in Asheville, Atlanta, Chattanooga, Columbus, and Knoxville. Columbus became a casualty almost immediately, dropping out due to poor attendance. The league went belly up on May 29, with the remaining teams reverting to independent operations.

Allandale saw its final baseball game of 1897 on September 15. About a dozen cranks turned out to see an informal game between mixed teams of Moonshiners and locals. Fifteen-year-old Stephen A. Lynch, already known as “Diamond,” donned the catcher’s equipment for one squad. Lynch went on to become fabulously wealthy in the movie distribution and real estate businesses before dying in Monaco in 1969.

Interest in baseball was dead on arrival in 1898, collateral damage of the Spanish-American War. An editorialist at the Citizen provided an appropriate eulogy for the game:

“This year we didn’t hear even an intimation that anybody wanted to see baseball, and the old-time crank reads all through the war news and puts his paper down without thinking of the national game. Cranks used to stop on the streets and discuss the chances of the Moonshiners, the Orioles, the Beaneaters or the Spiders. They don’t do it now. Instead you see them leaning up against a streak of sunshine, discussing the plan of campaign in Cuba and whether or not we will be able to fight the war to a speedy close without sending a fleet to Spain. Wondrous changes, indeed.”

Allandale fell into disuse. In 1899, the old ballpark was escorted into obscurity by a state tax of $5 on every game of baseball for which admission was charged. The Citizen honored the tax with a poem.

Allandale is deathly quiet, gone are all its old-time joys,

Never shall a brave Moonshiner raise a riot ‘mong the boys

With a large and luscious home run – get his picture in a frame —

We must settle with the sheriff every time we have a game!

In its final year of existence, Allandale hosted high school baseball and football games, an exhibition of baseball by the Boston Bloomer Girls, and a bullfighting demonstration. Among the final baseball games played at Allandale were those of Asheville’s new Black baseball club.

In October of 1899, Allandale’s grandstand, bleachers, and fence were dismantled. The lumber was donated to the Flower Mission, a local aid organization that wished to establish a woodyard to supply firewood to those in need.

The Asheville Baseball Club continued its tenuous existence, taking up residence in Riverside Park in 1900 and moving to Oates Park in 1913. Allandale was, at that time, still an empty field.

Perspective map of Asheville drawn by T.M. Fowler, 1912. Not drawn to scale. Library of Congress.

Perspective map of Asheville drawn by T.M. Fowler, 1912. Not drawn to scale. Library of Congress.

One hundred twenty-nine years after Allandale was carved into the hillside a minute’s walk from the Charlotte Street trolley line, the Asheville Tourists hosted Moonshiner’s Night to “celebrate the professional game’s earliest roots in Western North Carolina.”

The press release announcing the promotion maintained that the Moonshiners of 1897 “played games at Allandale Park, which was located near the French Broad River.” The Tourists’ publicist had confused Allandale Field with Riverside Park.

Allandale may be lost, its location forgotten. But the stone pitcher’s slab that Principal E.B. Lewis planted in 1894 may still rest in someone’s backyard off Hillside Street, shielding a decaying copy of the Asheville Citizen.