Billy Laval’s Spartanburg Red Sox and the Bad Series at Rock Hill

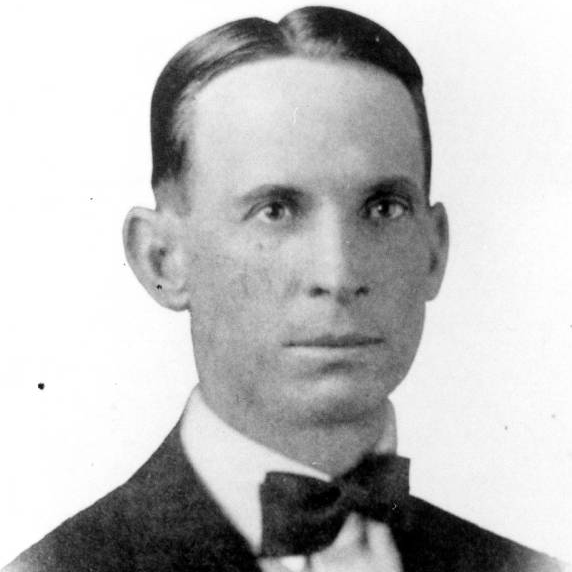

Billy Laval’s passion was coaching college football. Between 1915 and 1949, Laval’s teams compiled a record of 168 wins, 136 losses, and 17 ties, taking home three Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association championships. In 2009 the Columbia State newspaper declared, “Laval earned the right to be called the greatest collegiate coach in South Carolina athletics history.”

Billy Laval’s passion was coaching college football. Between 1915 and 1949, Laval’s teams compiled a record of 168 wins, 136 losses, and 17 ties, taking home three Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association championships. In 2009 the Columbia State newspaper declared, “Laval earned the right to be called the greatest collegiate coach in South Carolina athletics history.”

But that was all in the future. In 1912, Laval was the 27-year-old player-manager of the Spartanburg Red Sox of the Class D Carolina Association. The season before, Laval’s first as a manager, the club had finished fifth in the six-team circuit. Many thought that Laval was too immature to manage a professional baseball team.

The Carolina Association limited its teams to a 13-man roster with a total monthly salary of $1400. Most clubs carried three outfielders, four infielders, two catchers, and four pitchers. Injuries among the position players were frequent, and the pitchers were expected to fill in when needed. In a pinch, a manager could pick up a local semi-pro or college player for a game or two.

But Laval overspent on his star players. He couldn’t stay below the salary limit without reducing his roster.

Laval tried to get by with a three-man pitching rotation: Wild Bill Clark, spitballer Bill Smith, and Ira Hogue. Laval had been a good pitcher in his younger days, before his arm gave out and he moved to right field. He sometimes took the mound in garbage time, but when a reliever was required with the game on the line, Laval called on one of his starters.

Hogue – considered “husky” at five-foot-eleven and 175 pounds – bore the brunt of the workload. From May 30 through June 30, Hogue appeared in 13 of the 26 games Spartanburg played. He made 11 starts; on two occasions he started consecutive games. The Red Sox were 3-7-1 in the games Hogue started during the stretch. “Hogue seems to work every day for Spartanburg and he never wins,” the sports editor of the Greenville News observed.

Wild Bill Clark took the mound 11 times between May 30 and June 30. Bill Smith had a relatively normal month. He made only six appearances during the interval though two of them were starts on consecutive days. As temperatures rose above 90 degrees in late June, Laval’s pitchers began to run out of steam.

With the Red Sox stuck in third place and hovering around .500, an article appeared in the Spartanburg Journal headlined, WHAT’S THE MATTER WITH SPARTANBURG RED SOX? The writer contended that Laval had secured the most talented crop of position players in the Carolina Association, but the team had failed to meet expectations. The reporter pinned the problem on the pitchers, in particular the lack of them: “The Red Sox are sadly in need of pitchers and unless at least two more are secured and secured at once, the standing of the Spartans will not be so favorable in the percentage column.”

Laval lacked the motivational skills that later made him a successful college coach. Writing of the Spartanburg manager during the previous season, the sports editor of the Spartanburg Herald had said, “Laval is not a gentle speaker. But there are few managers who are. On the contrary, the most successful leaders of ball teams have been those who have had a harsh word ever ready for the proper moment.”

As a young manager, Laval was perhaps unable to discern the “proper moment” to use a harsh word when addressing his players. The Red Sox played indifferently, far below their perceived potential.

On Monday, June 24, the Red Sox opened a three-game series in Spartanburg against the second-place Charlotte Hornets. Wild Bill Clark took the mound and pitched a complete-game loss. Then, instead of completing the series in Spartanburg, both teams were shipped off to Rock Hill, a little South Carolina burg about 30 miles southwest of Charlotte.

Rock Hill was hosting the South Carolina Fireman’s Convention, drawing in firemen and their families from all over the state. The organizers thought that a pair of afternoon games between two professional teams would provide excellent entertainment for the attendees. The clubs were promised a share of the gate receipts.

Higher forces within the Carolina Association had pushed for moving the games to Rock Hill. The Anderson club, way out at the western tip of South Carolina, was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. A group of Rock Hill businessmen had expressed an interest in buying the team and relocating it to their town. The games between Spartanburg and Charlotte would provide the locals with a sample of the Carolina Association’s product.

Flags, bunting, and a large electric WELCOME sign greeted the visitors when the convention opened on Tuesday morning. In the Woodsmen’s Hall, attendees were bored educated by a series of Powerpoint presentations including “How Chimneys and Flues Should Be Built” and “The Necessity for Frequent Inspections of Buildings and the Beneficial Results Therefrom.”

Rock Hill, South Carolina, decorated for Independence Day in the 1900s.

Rock Hill, South Carolina, decorated for Independence Day in the 1900s.

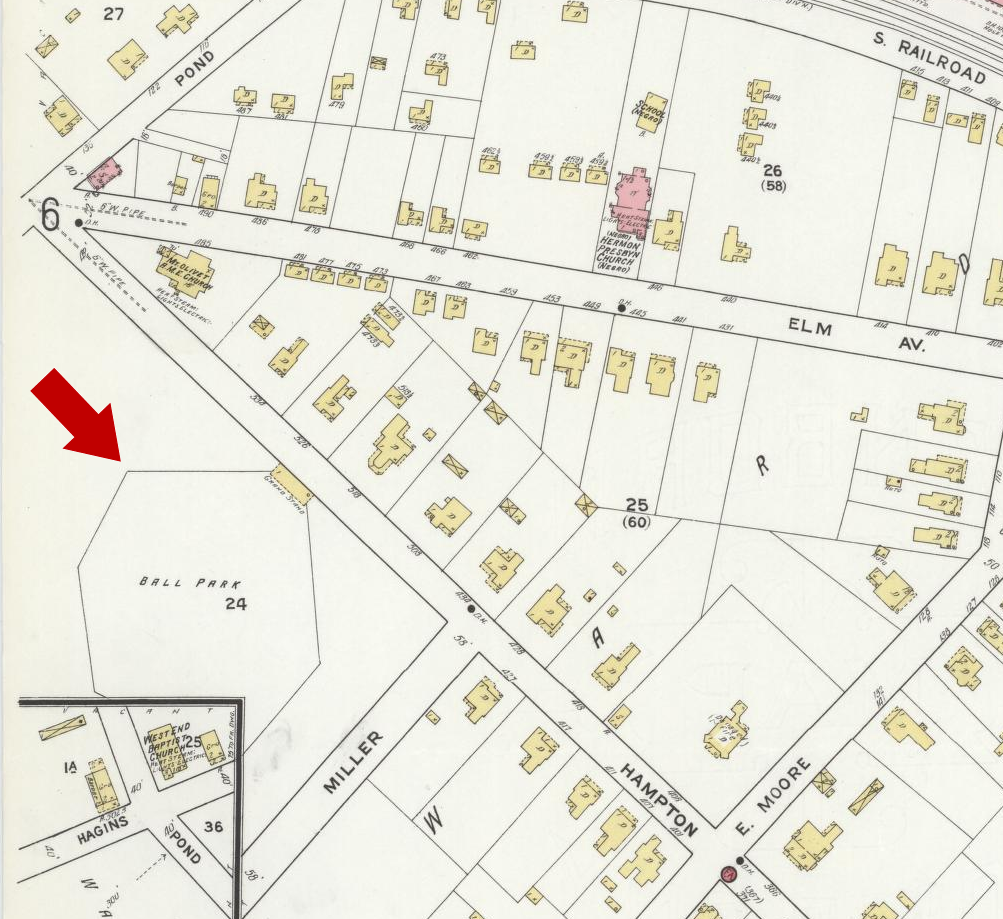

After lunch – or dinner, this being the rural South – a caravan of automobiles gave the visitors a tour of the city and brought them to the ballpark on the western edge of town, out on Hampton Street. A bank of dark rain clouds accompanied the cars to the ballpark.

Rock Hill’s park was a poor specimen, worse even than the dilapidated parks of the Carolina Association. It was a remnant of Rock Hill’s one-season membership in the now-defunct Class D South Carolina League.

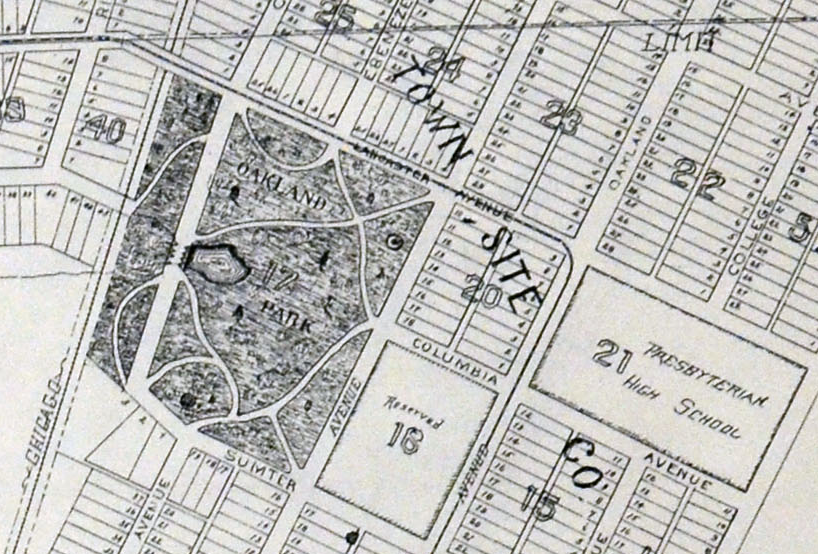

The Hampton Street grounds had begun life as a bicycle track. The grandstand and fences had originally graced Oakland Park’s athletic field, built in 1891 and located near the Campus Greens of modern-day Winthrop College. In 1908, the 17-year-old grandstand and fences were torn down, hauled out to Hampton Street, and reassembled to create a new ballyard. “The grounds are in pretty bad shape,” the writer for the Charlotte News said.

Rock Hill’s Oakland Park in 1891, the year the park’s athletic field was constructed.

Rock Hill’s Oakland Park in 1891, the year the park’s athletic field was constructed.

Rock Hill’s ballpark (red arrow) near the corner of Hampton and Miller streets in 1916. The grandstand is on Hampton Street, at the corner of the enclosed area. Accounts from 1912 mention both a grandstand and bleachers (uncovered seats). The bleachers appear to have been removed before 1916. The upper right corner is North. The inset in the lower left is a different map that was included on the sheet. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1916, page 11.

Rock Hill’s ballpark (red arrow) near the corner of Hampton and Miller streets in 1916. The grandstand is on Hampton Street, at the corner of the enclosed area. Accounts from 1912 mention both a grandstand and bleachers (uncovered seats). The bleachers appear to have been removed before 1916. The upper right corner is North. The inset in the lower left is a different map that was included on the sheet. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1916, page 11.

In prior years, the Spartanburg players had been Musicians. In 1912 they were rebranded as the Red Sox. The new name brought new uniforms. The “home suits” were pure white with SPARTANBURG across the front in red letters. A red S decorated each sleeve, and a white S blazed from the red cap. The stockings were white with a broad red stripe.

When Ira Hogue took the mound on Tuesday afternoon, his white uniform stood out against the dark clouds that looked ready to burst into a torrent at any moment. Nine hundred spectators completely filled the small grandstand and the bleachers and overflowed into foul territory. Those who hoped to see a fine example of the National Pastime were sorely disappointed.

Charlotte’s first batter, Johnny Agnew, singled. Two-hole hitter John Haddow’s sacrifice bunt was fielded by Hogue who held the ball with both runners being safe. Catcher Jack Coveney tried to catch Agnew leaning off second but threw the ball into center field as both runners advanced. Manager Champ Osteen brought Agnew home with a sacrifice fly, and Haddow scored when Red Sox second baseman Jack Corbett booted a grounder so badly that the batter made it to second. The runner went to third on a fielder’s choice and scored when Hogue uncorked a wild pitch. The score stood 3-0 in favor of Charlotte after the first inning.

The Red Sox gave up another run in the second inning. Shortstop Joe Kipp fielded a routine grounder and threw wild to first baseman Bart Woolums, allowing the runner to reach second. He moved to third on a sacrifice bunt and scored on a long fly to center. Score: 4-0, Charlotte.

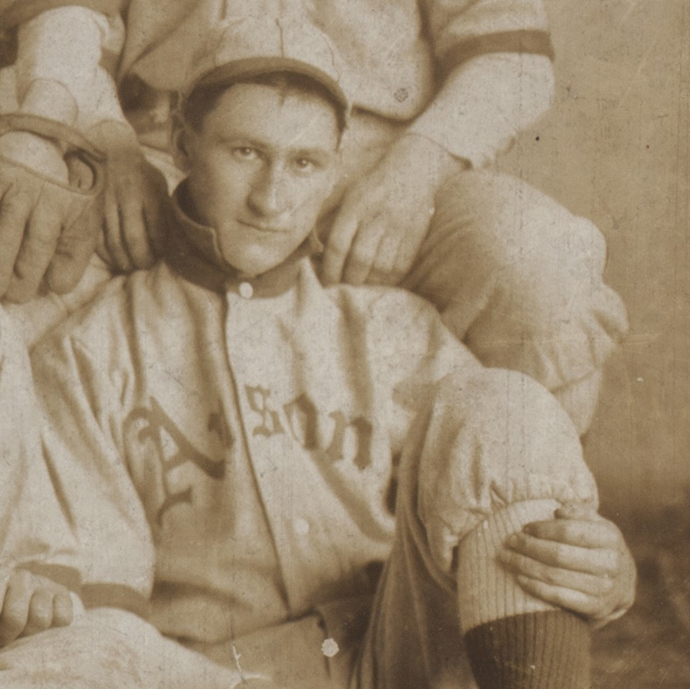

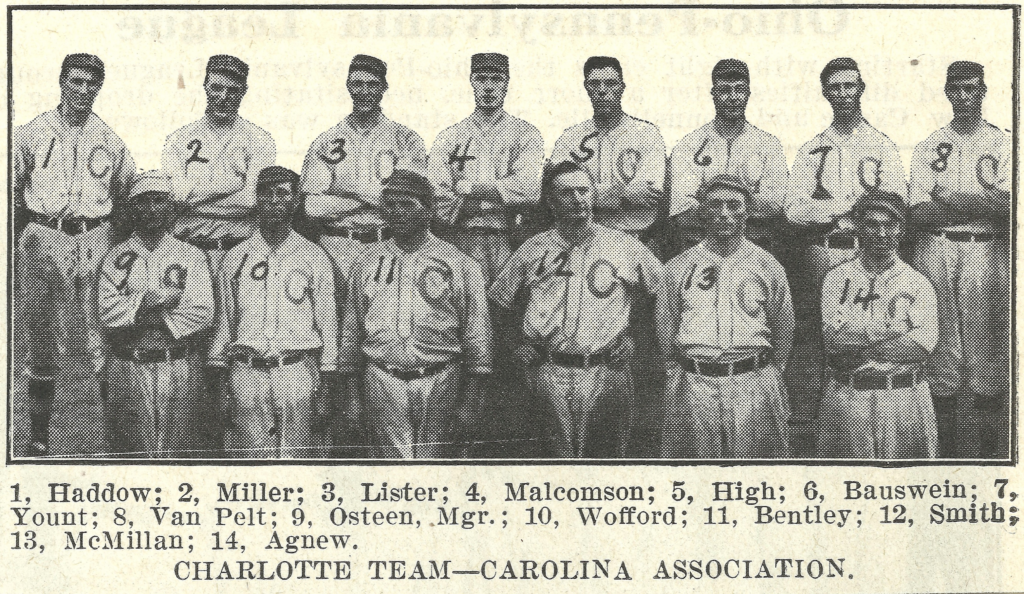

The Carolina Association’s Charlotte Hornets in 1912.

The Carolina Association’s Charlotte Hornets in 1912.

Doc High was on the mound for the Hornets. Nearly every southern team harbored at least one Doc or Dock. Some were actual doctors or dentists, others practiced minor surgery on the ball, but most of the labels were of unknown provenance. In the case of the Charlotte pitcher, the son of a Low Country farmer, it was not a nickname: his birth name was the aspirational Doctor Franklin High. His brothers included Henry Seymour High and Thomas Jefferson High, for whom hundreds of secondary schools have been named. High was a violence-prone player with a habit of pitching well in one inning, then falling apart in the next.

In the course of the game, High struck out six and gave up a single hit. But in the bottom of the second, he tried his best to help the Red Sox. With two down, High drilled Coveney and Hogue, walked Kipp, and let loose a pitch so wild that Coveney, a 32-year-old catcher, was able to plod across the plate. The Charlotte Evening Chronicle attributed the run to High’s “weirdness,” which was perhaps not an error by the Linotype operator.

Charlotte manager Champ Osteen homered in the top of the third inning to give the Hornets a 5-1 lead.

After Osteen’s homer, the Red Sox tried to gum up the works by playing as slowly as possible. If the rain that seemed imminent arrived before the fifth inning was completed, the game would count as a rainout rather than as a loss. Long intervals between pitches, excessive pickoff throws, walks to the mound by catcher Coveney, throws around the horn, calls for time, steps out of the batter’s box, numerous practice swings – all of the modern game’s hallmarks were employed. The delaying tactics, while legal, were unsportsmanlike. Considerable jawing resulted between the players, the umpire, and the fans who had paid a quarter to see a good, honest nine-inning game.

The hovering rain clouds were unimpressed by the players’ efforts — or lack of them — and held back their fury until the top of the sixth inning. When their waters were unleashed, they came in a torrent. One of the worst storms in memory ripped through Rock Hill, carrying away the flags, banners, and buntings that had gaily decorated the city for the convention. “The spectators scampered away from the park seeking shelter, the ball players being about the only visible parts of the humanity present when the worst of the tornado broke,” a witness recorded.

Since five innings had been completed, the game ended in another Red Sox loss. Spartanburg had tallied a single hit, played indifferently, and committed three errors. The Charlotte Evening Chronicle remarked on Spartanburg’s “generally poor and lax fielding” and labeled the support given Hogue “putrid.”

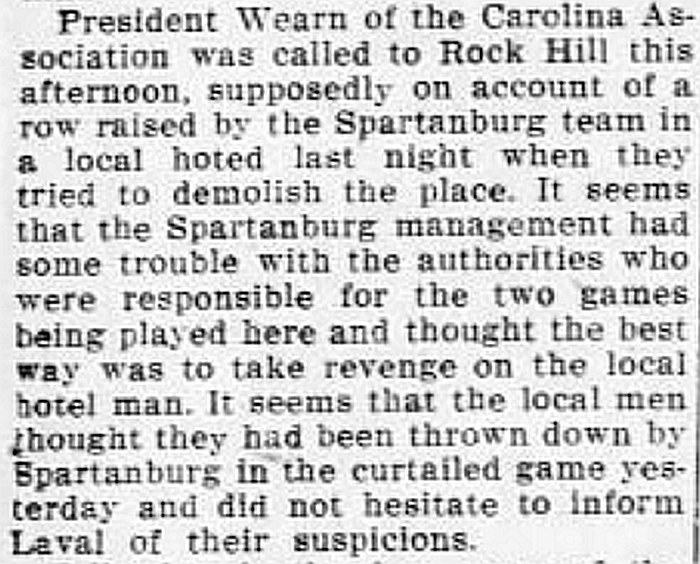

Back in Rock Hill, the organizers of the event went to Laval and accused the Red Sox of playing poorly on purpose, particularly during the final three innings when their purpose was to not play at all. As reported by the Charlotte News on Wednesday, “It seems that the local men thought they had been thrown down by Spartanburg in the curtailed game yesterday and did not hesitate to inform Laval of their suspicions.” There was talk of holding back the gate receipts that had been promised to the team.

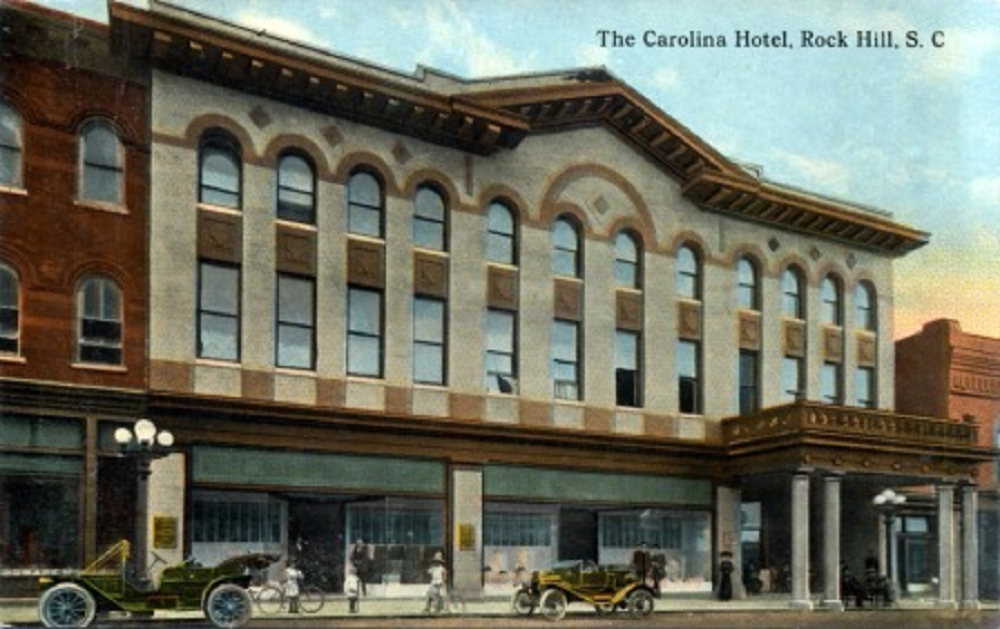

Rock Hill’s Carolina Hotel in 1910.

Rock Hill’s Carolina Hotel in 1910.

As the storm raged, the Red Sox and Hornets retired to the Carolina Hotel where both clubs were booked. It was all too much for the Spartanburg players: the losses, the rain, the fans, the firemen, the trip to the Rock Hill backwater, and now the trouble with the locals. The players responded in the time-honored fashion of frustrated young men everywhere, by getting drunk and trashing their hotel rooms.

At 1 AM someone awakened the proprietor of the hotel – a Mr. Stone who was, apparently, a sound sleeper – and told him that the racket had aroused the entire establishment. Stone went up to the Spartan’s rooms, found the players intoxicated and their furniture destroyed, and asked them to hold it down for the sake of the other guests. For his trouble, Mr. Stone received the cursing that only a group of drunken Class D ballplayers could deliver. He then called in the police who restored order by threatening to haul the entire lineup to the city jail.

The next morning when the Hornets and Red Sox gathered in the hotel dining room, another row ensued. Mr. Stone told Laval to take his team and hit the streets. The organizers of the convention, already on the outs with the Red Sox, let Laval know that Spartanburg would not receive its money until the hotel was reimbursed for the damages.

At 9 AM a grand parade trooped down Main Street. The Red Sox were no doubt far away from the crowd. Thumping drums and blaring trumpets would have been the last things their heads wanted to hear.

The hose wagon races took place just before game time. A fire wagon drawn by a single horse and bearing a reel of hose and a crew of firemen would careen 200 yards down Oakland Avenue. At the midway point, two firemen holding one end of the hose would bail out, throw the hose in a hitch around a hydrant, and start connecting the coupling. The remaining crew would continue paying out the hose to the terminus of the course where they would eagerly await the flow of water. If the hose blew off the hydrant, the team was disqualified.

The Newberry team won the $150 first prize with a time of 29 and four-fifths seconds from start to first water. Hamilton Carhartt, owner of the local overall factory, presented each participant with a pair of his product. The Red Sox probably avoided the hose wagon races, as the event was serenaded by the Carhartt Factory Band.

By afternoon the playing field had dried out sufficiently for the game to begin. A crowd of 1400, fired up by the exciting hose wagon races, again filled the grandstand, bleachers, and any available space along the foul lines. As the Spartanburg players sullenly took their positions, the sports editor of the Greenville Daily News, who knew a hangover when he saw one, noted that “the Red Sox must have been on a jag of some kind the night before.”

The first inning gave the fans hope of seeing a real ballgame. Spitballer Bill Smith faced six batters, giving up a single run. In the bottom of the first, Spartanburg shortstop Joe Kipp reached first on a leadoff single before the next three Red Sox were retired.

Whatever competence Smith had retained after a night of drinking was expended in the first frame. In the second inning, he gave up five runs, including a three-run homer, while recording two outs.

Laval replaced Smith with Harry Hipfel, a New Jersey semi-pro in town for a tryout. Hipfel — captured in the box scores as Hippel or Hipsel — failed the audition, surrendering five runs before recording the inning’s final out. Hipfel left the park and was never seen in South Carolina again.

From that point on there was no doubt that the Red Sox were making only the minimal effort required to get through nine innings.

Billy Laval took the mound and gave up eleven hits and six runs in three innings. Charlotte pitcher Van Pelt led off the fifth with a single then, as reported by the Charlotte Observer, “went around the sacks on three wild throws of the Spartans who seemed that they did not care whether the throws were true or treacherous.” After that, Laval served up batting practice, allowing most Hornets to hit twice, and surrendered three consecutive homers in one span. The majority of the spectators, unable to understand how this display was worth a quarter, left the park.

Spartanburg center fielder Ed Doak came in for the final four innings. He allowed only four runs, but was aided by the Hornets who were just trying to get the game over with. Any batter who put the ball in play would simply trot around the bases until tagged.

The final damage: a 21-0 loss for the Red Sox, their fourth in as many games. The Hornets tallied 14 singles, a double, a triple, five home runs, eight walks, and two hit batsmen. Spartanburg made only four hits and committed seven errors.

Bart Woolums, the regular Red Sox first baseman, was, curiously, absent from Wednesday’s game. He was said to be suffering from a badly bruised heel that was threatening to develop into blood poisoning.

The behavior of Laval’s team was a major scandal around the circuit. The worst words came from the Rock Hill Record:

Rock Hill people have seen all sorts of ball and played by all kinds of teams except of course the National and American Leagues, and a goodly number of our people have seen games in those leagues; but the “rottenest” exhibitions that have ever been offered to intelligent people were those pulled off between Charlotte and Spartanburg on Tuesday and yesterday afternoons. We will admit in advance that the Charlotte team wanted to play ball, but Spartanburg never made any attempt whatever at playing.

Tuesday afternoon, as soon as Spartanburg saw that a rain was in sight, they simply quit the game and fooled along trying to delay so that the umpire would call it before the end of the fifth inning.

Wednesday afternoon the Charlotte team started in and made five scores in the first inning [the writer’s indignation apparently prevented him from perusing the box score], and from that on Spartanburg never made any attempt to play ball at all; just let Charlotte run around the bases so that they could get out, and even with this Charlotte ran around 21 times to Spartanburg’s nothing and could have easily gone a dozen more.

It was simple robbery to take the people’s money and the worst feature of it was the taking of money for such an exhibition from visitors in the city from all parts of the State.

And after summarizing the activities at the Carolina Hotel, the writer concluded:

There have been a good many here who favored league ball and considerable talk at times of trying to get Anderson’s place in the Carolina Association; but we think the exhibitions pulled off here will take all of the “ginger” out of any one and make them lose interest in going out to see a lot of “sots” who had the audacity to say, when some criticized them for the manner in which they were doing, “that the pay was going on just the same.”

Carolina Association president J.H. Wearn came down from Charlotte for a firsthand inspection of the damages in the Carolina Hotel. The Hornets were rumored to have been involved in the destruction, but they had a guardian angel: League President Wearn was also the owner of the Charlotte club. Wearn was a man of massive ego who enjoyed naming things after himself. The Hornets played in Wearn Field, just across Winona Street from the Wearn Lumber Company. President Wearn protected his club from condemnation.

Excerpt from a story in the Charlotte News describing the events in Rock Hill, June 27, 1912.

Excerpt from a story in the Charlotte News describing the events in Rock Hill, June 27, 1912.

Leaving Rock Hill, the Red Sox moved on to Anderson where Clark, Smith, and Hogue each pitched a complete-game loss, extending Spartanburg’s losing streak to seven games. The team was obviously out-of-sorts, kicked excessively, and two players were fined and ejected in the second game. Rumors that Laval had been canned were making the rounds.

The week ended with Spartanburg in fourth place bearing a 26-29 record. The team’s batting average, .246, was fourth-best in the six-team Carolina Association. Their fielding average of .940 was dead last.

Spartanburg club president B.S. Doolittle and secretary E.O. Frierson made a thorough investigation of the players’ conduct in Rock Hill. Monday morning at 8:30 AM, the first day of July, the Red Sox trooped into the office of Mr. N.S. Trakas, vice president of the club. Messrs. Doolittle and Frierson presented the results of their investigation, went over the evidence in detail, and interrogated the players.

As reported in an official statement released after the meeting, the directors determined “that certain members of the Spartanburg team (with a few of the Charlotte players, sub-rosa) had indulged freely in riotous revelry.” The directors then took the action “which they deemed was best for the club, for baseball in Spartanburg, and for the good of the Carolina Association.”

Laval was fired as manager and given his unconditional release. In their statement, the directors said, “The thing that caused the most worry was the fact that Manager Laval had not shown the proper authority over his men, and the realization that his usefulness to the Spartanburg base ball club had reached an end.”

A slight sticking point was the ownership of the club. President Doolittle and Vice President Trakas owned two-thirds of the Red Sox. The remaining third was owned by Billy Laval, who had purchased an interest in the club earlier that year. In order to make a clean break with their former manager, Doolittle and Trakas agreed to buy out Laval’s interest, compensating him for whatever money he had invested.

It was an incredible windfall for Laval since his shares in the Red Sox were worthless. Investing in a Class D minor league franchise was the equivalent of stuffing dollars into a coffee can and setting them on fire. The Spartanburg club had been losing money from the moment of its inception and would go bankrupt at the end of the season. After being relieved of his managing burdens and receiving a golden parachute, Laval must have walked from the office of Mr. Trakas with the ballsy gait of a gambler who has finally evened the balance with his bookie.

Several players, labeled “the ring leaders in the Rock Hill affair,” were heavily fined. The discretion that dominated social interactions of the day preserved the anonymity of the punished players, but all were reported to have “professed sorrow at this lapse from discipline and promised that there would be no recurrence of the like.”

First baseman Bart Woolums was named the new player-manager. It was a surprising choice. Woolums was barely 23 years old, was in his third professional season, and had been with the Red Sox less than three weeks. But Woolums was known to be “a lad of splendid habits.” He was probably the only man on the roster who had not been intoxicated in Rock Hill. His absence from the 21-run farce, blamed on a bruised heel, was no doubt due to a desire to distance himself from the sordid affair.

In normal circumstances, the manager’s job would have gone to 31-year-old Wild Bill Clark, who had managed in the South Atlantic League the previous year, or to 32-year-old Jack Coveney, who had managed in the New England League back in ’07. The bypassing of these qualified players in favor of the inexperienced Woolums was an indicator of their culpability. But all of the remaining Red Sox, including those who were disappointed at being passed over for the top job, pledged their support to their new manager.

The players left the office of Mr. Trakas, somewhat poorer than when they entered, and caught the interurban trolley to Greenville for the next series. Wild Bill Clark pitched a complete-game loss on Monday afternoon. Bill Smith followed with a complete-game loss on Tuesday to give Spartanburg a nine-game losing streak. Finally, on July 3, Hogue came through with a 10-inning complete-game win to give the fourth-place Red Sox a 27-31 record.

—

Ira Hoque earned his unconditional release on July 28. “There is no doubt that he was a splendid pitcher, with all the benders and breakers in the vocabulary, but when it came to winning games he was not there, and the fans, players and all went down in defeat through the inability of Hogue to work out his game in the face of trying circumstances,” the Spartanburg Journal lamented. “To save themselves from further humiliation it was decided to let Hogue go.” He departed Spartanburg with a record of 7-16-1.

Later in the season, Hogue and Billy Laval both caught on with the Anderson Electricians.

Spartanburg continued to play poorly, finishing the season in fourth place with a 54-55 record.

The Carolina Association folded at the close of the 1912 season. In 1913, the Charlotte, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem clubs joined Raleigh, Durham, and Asheville in the new North Carolina State League.

Spartanburg did not recapture minor league baseball until 1919 when the Spartanburg Pioneers entered the Class C (later Class B) South Atlantic League.

Rock Hill, perhaps having experienced too much minor league baseball during the two-game series between Spartanburg and Charlotte, avoided professional baseball for 34 years. In 1947, the Rock Hill Chiefs joined the Class B Tri-State League. The team president was 62-year-old Billy Laval, who owned one-third of the club’s shares.