Spartanburg’s Unique Carolina Association Ballpark

Spartanburg, South Carolina, is sited on the Piedmont Plateau between the more crowded civilizations of Charlotte and Greenville. Thomas Wolfe, in Look Homeward, Angel, described Spartanburg as a “sleepy junction” within a “hot baked autumnal land, rolling piedmont and pine woods.”

Spartanburg, South Carolina, is sited on the Piedmont Plateau between the more crowded civilizations of Charlotte and Greenville. Thomas Wolfe, in Look Homeward, Angel, described Spartanburg as a “sleepy junction” within a “hot baked autumnal land, rolling piedmont and pine woods.”

In the early 1900s, Spartanburg was a mill town with a permanent population of around 15,000, where cotton was spun into thread, yarn, and cloth. Homes built for the mill workers still line Spartanburg’s shady streets. Many of the workers were children who ran barefoot through the sandy fields and manure-strewn streets, and whose homes were served by outhouses. Intestinal ailments due to hookworms and tapeworms were widespread.

The area was plagued by pellagra, a disease caused by a diet limited to the Three M’s: meal, molasses, and meat — primarily fatback. The results were the Four D’s: diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death. Research conducted at the Spartanburg Pellagra Hospital helped establish that the sickness was caused by a nutritional deficiency — lack of niacin — and not by germs or bacteria.

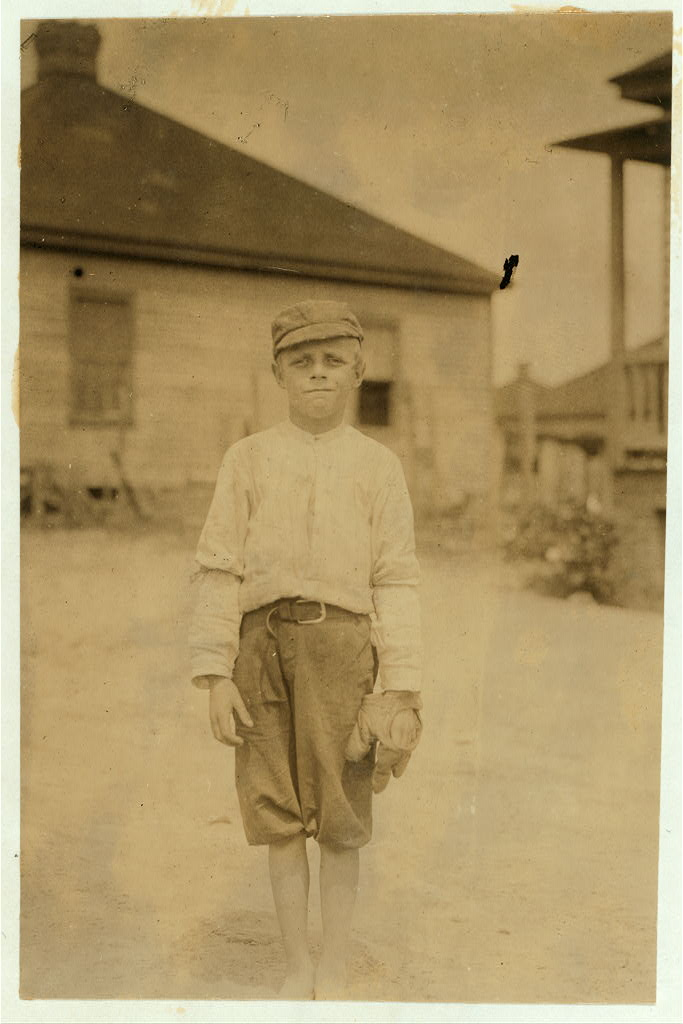

Lloyd McAbee, ready for a game of baseball in May of 1912. Lloyd worked in a Spartanburg textile mill as a doffer: a boy who changed out the spindles on a spinning frame. Lloyd’s mother claimed that he was 12 years old. Library of Congress National Child Labor Committee Collection.

Lloyd McAbee, ready for a game of baseball in May of 1912. Lloyd worked in a Spartanburg textile mill as a doffer: a boy who changed out the spindles on a spinning frame. Lloyd’s mother claimed that he was 12 years old. Library of Congress National Child Labor Committee Collection.

The Spartanburg ball club began life in 1907 as a member of the Class D South Carolina State League. Just prior to opening day, the owners invited local fans to suggest a nickname for the team. After considering over 200 submissions, they chose “Musicians,” the name suggested by Charles O. Hearon, the editor of the Spartanburg Herald. Spartanburg had recently hosted the South Atlantic States Music Festival, featuring performances by the New York Symphony Orchestra, and the town had music on its mind. Editor Hearon was awarded a season ticket to all of the Musicians’ home games.

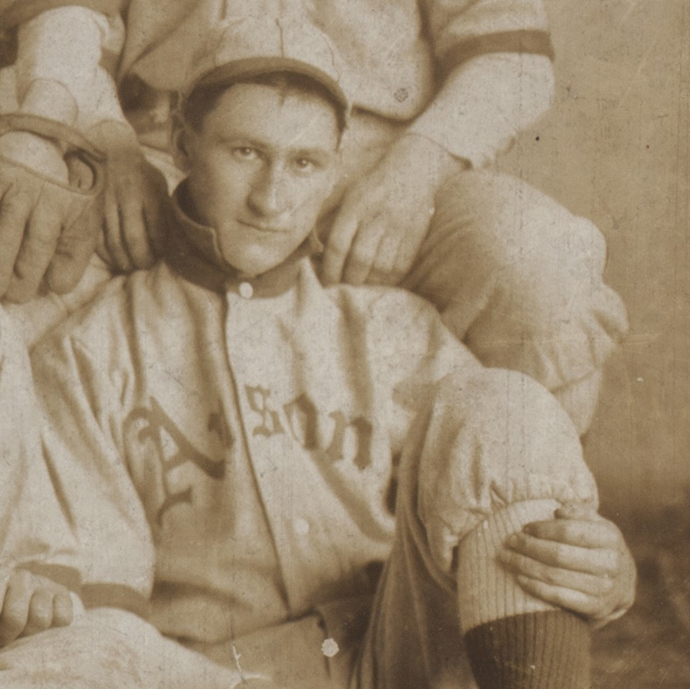

The club was known as the Musicians until 1912 when it was rebranded as the Red Sox. The creative sportswriters of the day often referred to the team as the Spartans. Modern references and databases now universally — and incorrectly — list “Spartans” as the team’s official name.

Following the demise of the South Carolina State League, Spartanburg joined the newly organized Carolina Association in 1908. The Class D league comprised clubs in six small towns strung out along the Piedmont Plateau: Winston-Salem, Greensboro, Charlotte, Spartanburg, Greenville, and Anderson. The towns were connected by the Southern Railway tracks that ran along the crest of the plateau.

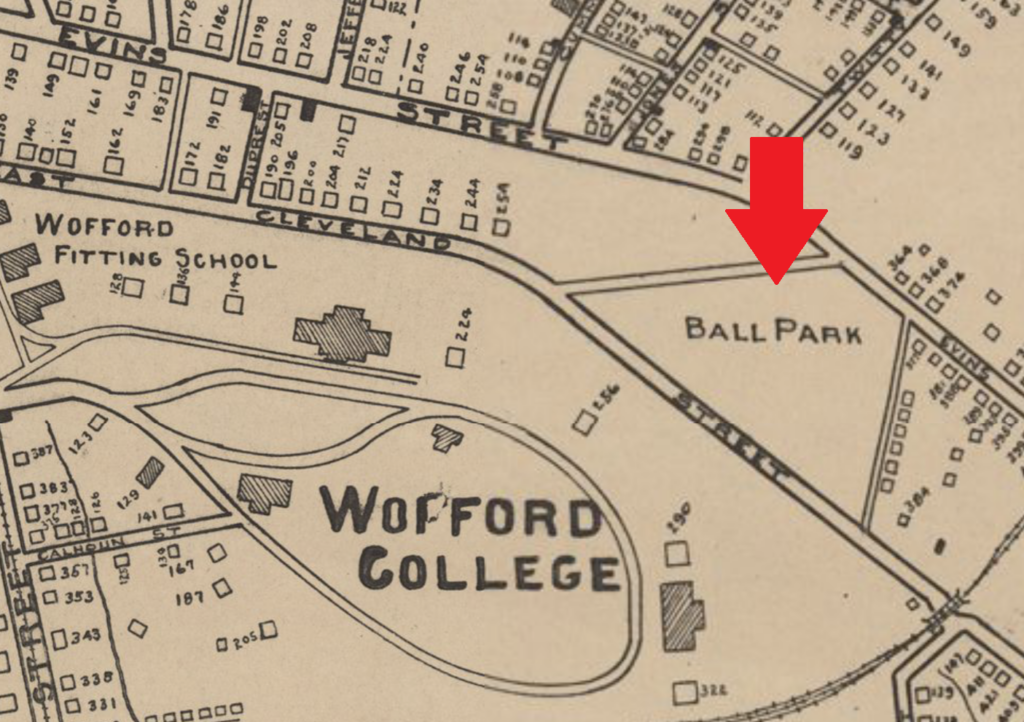

The Musicians probably spent their 1907 and 1908 seasons at the ballpark of Wofford College, located adjacent to the campus between Cleveland and Evins streets. The ballpark featured a small grandstand flanked by an uncovered section of bleachers.

Wofford College ballpark as it appeared on the Spartanburg city map created in 1910 and revised in 1912. The streetcar line is in the lower left corner on Church Street. The tracks in the lower right corner are the Carolina Clinchfield & Ohio Railroad.

Wofford College ballpark as it appeared on the Spartanburg city map created in 1910 and revised in 1912. The streetcar line is in the lower left corner on Church Street. The tracks in the lower right corner are the Carolina Clinchfield & Ohio Railroad.

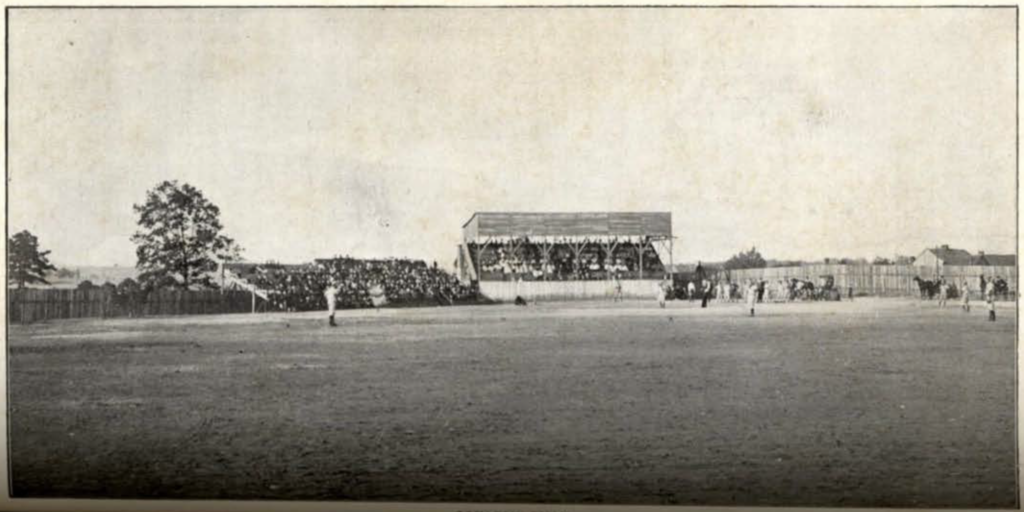

Baseball game in progress at the Wofford College ballpark. Horse-drawn carts are parked along the fence on the third base side. Wofford College catalog, 1908-1909.

Baseball game in progress at the Wofford College ballpark. Horse-drawn carts are parked along the fence on the third base side. Wofford College catalog, 1908-1909.

On the afternoon of Wednesday, July 24, 1907, Spartanburg’s ballpark hosted a game between the Musicians and the Greenville Mountaineers. Four women “of shady character,” who were probably on better-than-speaking terms with a few of the players, turned out to support their team. After paying their quarters, the ladies took prominent seats in the grandstand and enjoyed the entire nine-inning affair.

Unfortunately, the ladies had violated the town’s strict code of conduct. “It is an unwritten law in Spartanburg that women of the underworld are not allowed to sit in the grand stand,” the Orangeburg Times and Democrat wrote in an editorial the following week. “As they came out of the park a police officer took the women in charge and sent them to police headquarters, where a case of vagrancy was booked against them.”

The Times and Democrat’s editorialist decried the unfairness exhibited by the authorities: “It seems pretty tough to take the money of the unfortunate women for seats and then have them arrested for occupying them.”

The Musicians’ original ballpark had a major defect in the eyes of the fans: it was too far from the Church Street trolley line. And while some fans, like the ladies of shady character, were willing to slog down the unpaved avenues and across the Wofford College campus in the blistering heat of a South Carolina summer to watch a baseball game, most were not. “The ball lot was a quarter of a mile from the nearest car line and this materially reduced attendance,” the Charlotte Observer reported.

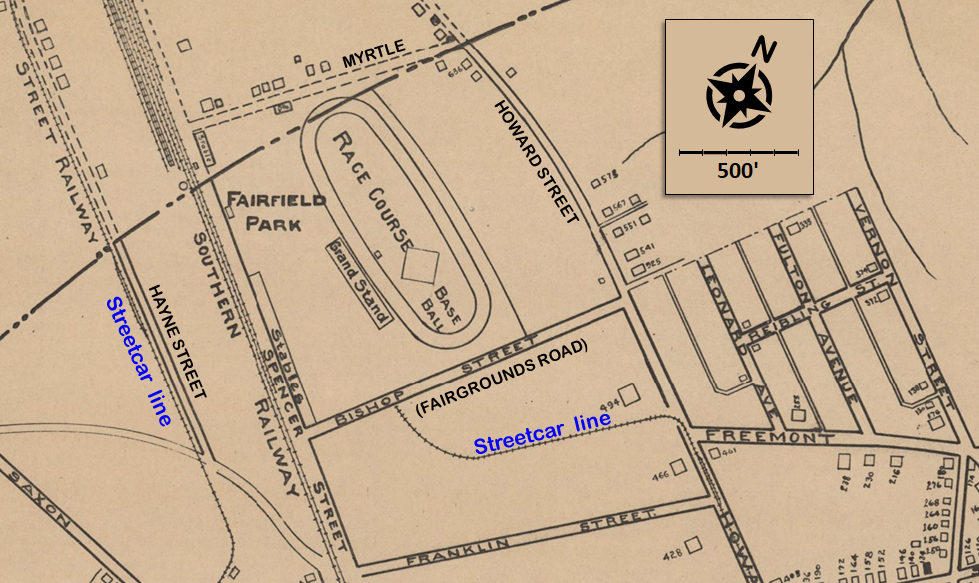

To better convenience the paying customers and boost attendance, a new baseball diamond was scratched out within the half-mile oval of the Fairfield Park harness racing track prior to the 1909 season.

Fairfield Park sat at the terminus of the Howard Street trolley line. The tracks ran up Howard Street from downtown Spartanburg. Just past Freemont Street, the line angled over between Franklin Street and Bishop Street (now Fairgrounds Road), coming to an end just across Bishop from the racetrack.

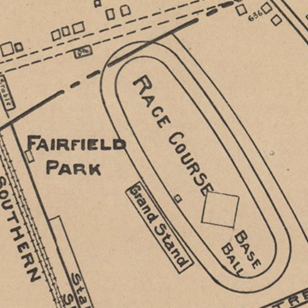

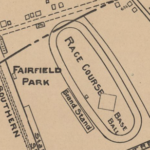

Fairfield Park and surrounding streets, 1910 city map (revised 1912). The baseball diamond is oriented incorrectly, showing a structure within the field of play.

Fairfield Park and surrounding streets, 1910 city map (revised 1912). The baseball diamond is oriented incorrectly, showing a structure within the field of play.

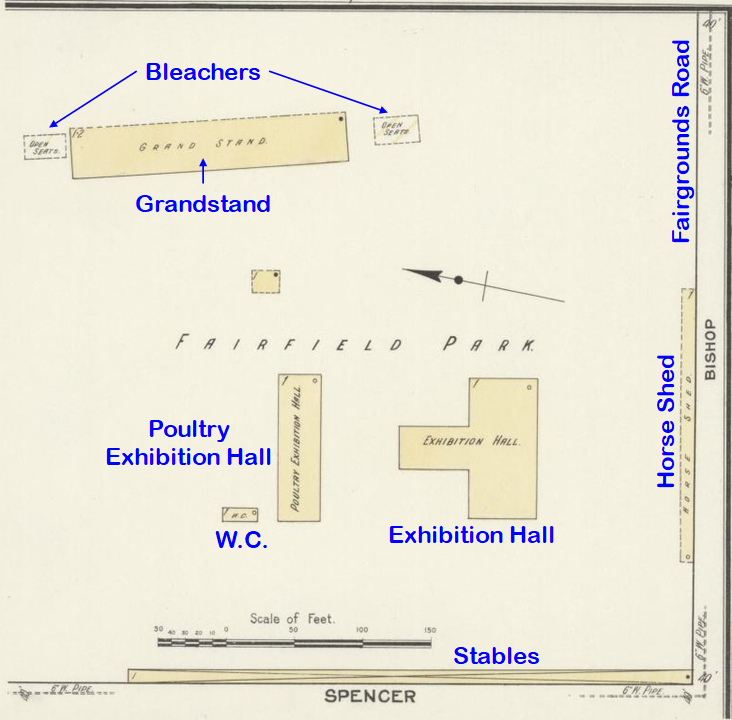

A Sanborn Fire Insurance map published in September 1912 depicts the Fairfield Park structures located at the corner of Spencer and Bishop. A grandstand over 150 feet long and two small sections of bleachers face the racetrack. One section of bleachers was probably reserved for Black spectators. The park was said to host seating for 2000 fans.

A horse shed fronted Bishop Street, while a row of stables lined Spencer. The property also contained two exhibition halls, one for poultry, and a W.C.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, September 1912, page 33.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, September 1912, page 33.

The racetrack had been in use at least since November of 1907 when Fairfield Park hosted the first Spartanburg County Fair. Over 11,000 spectators, most of whom had bought a ticket, filled the park, overflowing the grandstand and lining the racetrack. Get Away, an import from Sumter, set a track record for the one-mile dash, supposedly tearing around the oval twice in one minute and forty-eight seconds. It was an unlikely time given that it equals the current North American record.

The most unique feature of Fairfield Park was the location of the baseball diamond: inside the racetrack. The fence around the outside of the track formed the outfield fence.

An aerial photograph taken in 1950 reveals the approximate location of the playing field. Nearly 40 years after the demise of the Carolina Association, the ghostly image of the diamond was still visible.

Aerial photograph of Fairfield Park racetrack, 1950. Provided by Historic Racetrack Aerials (Twitter @RacingAerials).

Aerial photograph of Fairfield Park racetrack, 1950. Provided by Historic Racetrack Aerials (Twitter @RacingAerials).

Julian S. Miller, the “sporting editor” of the Charlotte Observer, described the ballpark: “The diamond is surrounded by the race track. The fence is very far away and there is no danger of a ball being knocked over it. Home runs will be numerous, however, for if a ball ever gets beyond a fielder it will roll half-way around the track.”

Miller’s description of the fence as “very far away” was an understatement. Using the aerial photograph as a guide for locating the diamond and the outer edge of the track, and using a Google satellite image to measure the distance from home plate to the fence, it appears that the ballpark had approximate dimensions of 900′ to left field, 445′ to center, and 375′ to right.

Google Maps satellite image of Fairfield Park with distances from home plate to the racetrack’s outer fence. Measurements by Google Maps.

Google Maps satellite image of Fairfield Park with distances from home plate to the racetrack’s outer fence. Measurements by Google Maps.

Early in the 1909 season, in a game against the Winston-Salem Twins, Spartanburg pitcher Cliff Averett and second baseman Harvey Ritter smacked what would become typical Fairfield Park homers. “Averett hit a home run to deep left with one man on base,” the Charlotte Observer told its readers. “It was the longest hit of the season, rolling all the way to the left field fence beyond the race track. Ritter also hit a homer to centre, the ball getting beyond Carter.”

The “Carter” in question was Robert Love Carter, the Twins’ player-manager and one of the best center fielders in the league. But even the speediest outfielders had difficulty covering Fairfield Park’s massive outfield.

In 1910 the Blackwell Durham Tobacco Company began installing its famous Bull Durham signs in minor league ballparks around North Carolina. By 1911, a bull grazed along the outfield fence of nearly every professional ballpark in the country. Any player who hit the bull with a fairly batted fly ball received a check for $50. And any player who hit a home run received a carton — 72 packages — of Bull Durham smoking tobacco. Homers of both the inside-the-park and over-the-fence varieties were awarded the prize.

Fairfield Park’s bull was installed somewhere along the right field fence. The bull’s distance from home plate assured that it would remain unmarred.

During the 1911 season, no one hit the bull in Fairfield Park but none of the other Carolina Association bulls were impacted, either. Twenty-six homers were recorded in Spartanburg, resulting in the distribution of 1872 packages — 117 pounds — of tobacco.

In 1912, Carolina Association bulls were struck five times. The Spartanburg bull was undamaged. Only 13 home runs were hit in Fairfield Park, giving the lucky players 936 packages of tobacco totaling a mere 59 pounds.

Carolina Association ballparks were poorly-groomed affairs featuring clumps of patchy grass struggling to survive in the chert-strewn sapropel. On a blazing hot day in late July of 1912, the ground of Fairfield Park helped Winston-Salem outfielder Red Stewart earn 72 packages of tobacco.

The Greensboro Champs working out in Greensboro’s Cone Athletic Park, probably early in the 1909 season. The bumpy field was typical of the Carolina Association ballparks. Bernard Cone Collection.

The Greensboro Champs working out in Greensboro’s Cone Athletic Park, probably early in the 1909 season. The bumpy field was typical of the Carolina Association ballparks. Bernard Cone Collection.

Stewart stepped to the plate in the seventh inning with the Twins trailing 0-2 and two men on base. He faced Ira Hogue, an overworked hard-luck pitcher bearing a 7-14 record. Down two strikes in the count, Stewart lined a should-have-been single straight at Spartanburg right fielder Whiskers Weir.

The sportswriters who served the Carolina Association’s newspapers were young men in their 20s who were marking time until the next challenge of Life came along. Their exuberant prose sometimes seemed inspired by the contents of a flask.

“Stewart laid back on one that knocked the wine out of the horseshoe and the juice scattered all over Fairfield Park,” the scribe of the Spartanburg Journal wrote. “He lined out a terrific drive to Weir’s territory, which took a bad bound and went shying over the head of the right gardener to the race track, where it found a resting place under the shadow of the big ‘Bull’ sign. The hit came at a time when things were ripe for a Waterloo and when the three men crossed the plate there was no more joy in the home land and the fans set up the tune the cow died by.”

Stewart’s homer won the game, giving Hogue another loss and presaging his release the following week.

Fairfield Park could not have provided an ideal experience for the fans. The grandstand was a great distance from the diamond and fans were separated from the field by the wide expanse of the racetrack. The grandstand was often more than half-empty.

In the 1912 preseason, Spartanburg was thought to have the strongest lineup in the Carolina Association, but the Red Sox underperformed and played uninspired ball. The fans loudly criticized the team. During a June game, Spartanburg manager Billy Laval finally got fed up. He walked to the edge of the track, faced the grandstand, and let loose a stream of unprintable invective that only a Class D ballplayer could deliver.

The Spartanburg Journal took Laval to task: “Laval ought to be man enough to take the criticism of the fans without ‘chewing the rag’ with men who paid their 25 cents to see the game.”

Attendance declined through the 1912 season. Only 175 fans took the streetcars to Fairfield Park for the final game, played on Labor Day in temperatures that approached 90 degrees.

The Carolina Association was reorganized in 1913 as the North Carolina State League, dropping Spartanburg, Anderson, and Greenville and adding teams in Asheville, Raleigh, and Durham.

Spartanburg was devoid of professional baseball in 1913. The following year the town fielded a team in the Piedmont League, an independent circuit with clubs in Anderson, Greenville, and Gaffney. Games were played at Wofford Park. From 1915 through 1918 Spartanburg amused itself with various semi-pro leagues. The Asheville Tourists scheduled four exhibition games in Spartanburg prior to the 1915 season, but the series was canceled after only 63 fans turned up for the first game.

Fully professional baseball returned in 1919 when the Spartanburg Pioneers entered the Class C (later Class B) South Atlantic League. Games were played in Wofford Park. Fans still complained about the muddy streets leading to the park, and in late 1920 Cleveland Street was paved from Wofford Park to Church Street.

The Spartanburg club became the Spartans in 1922. The team finally got a modern home in 1926 when the city spent $30,000 to construct Duncan Park. The club went belly up in the final days of the 1929 season and was dropped from the league. Duncan Park is now used by Spartanburg High School, an American Legion team, and the Spartanburgers of the Coastal Plain League. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Fairfield Park continued to host harness racing events into the 1930s. After World War II, the park became the Piedmont Interstate Fairgrounds and began hosting stock car races. Between 1953 and 1966, twenty-two Grand National Series races took place on the oval that had seen horses, baseballs, and wooden bulls.

Today the half-mile oval is disused and in disrepair, but still recognizable as a racetrack. The baseball diamond and the players who chased baseballs through the park’s massive outfield have been completely forgotten.

Piedmont Interstate Fairgrounds, May of 2022. The baseball diamond was probably sited between the shed in the foreground and the open picnic pavilion. The covered grandstand occupied the same ground as the modern stands. The dirt racetrack is in the foreground.

Piedmont Interstate Fairgrounds, May of 2022. The baseball diamond was probably sited between the shed in the foreground and the open picnic pavilion. The covered grandstand occupied the same ground as the modern stands. The dirt racetrack is in the foreground.