The Glorious Life of a Class D Ballplayer in 1909

Excerpts from the in-progress biography of Jack Corbett entitled The Book About Jack Corbett and a Lot of Other Stuff. Corbett began the 1909 season playing for the Charleston Sea Gulls of the Class C South Atlantic League. A good infielder who was outmatched by Class C pitching, Corbett was released, bearing a .174 batting average, after appearing in 15 games.

Excerpts from the in-progress biography of Jack Corbett entitled The Book About Jack Corbett and a Lot of Other Stuff. Corbett began the 1909 season playing for the Charleston Sea Gulls of the Class C South Atlantic League. A good infielder who was outmatched by Class C pitching, Corbett was released, bearing a .174 batting average, after appearing in 15 games.

Two hundred thirty miles upcountry from Charleston’s tidal flats, in the Class D Carolina Association, the Anderson Electricians needed a second baseman.

On May 18, Louis B. Miller, the Electricians’ regular second baseman, stepped into a pitch from Charlotte Hornets pitcher Charles Ellinor. The ball struck Miller’s bat near the handle, caromed into his chest with terrific force, and ricocheted upwards against his chin. Miller immediately dropped into the dirt, completely unconscious. He regained his feet long enough to stagger off the field, supported by a player on each side, then again passed out. Miller was hauled to the hospital where he was found to possess a fractured rib over his heart.

Anderson’s next two games were rained out, giving Electricians manager Jim Kelly time to recruit a new second baseman. He found one in the form of James Wideman, a high school teacher, law student, and former captain of the Erskine College baseball team. Wideman appeared in three games with Anderson, going 5-for-12 at the plate but committing an error in each game. Wideman asked for his release and returned to his home in Due West.

Minor league managers kept one ear glued to the baseball grapevine. Kelly perhaps heard that Charleston had released a slick-fielding infielder and sent a southbound telegram in search of a second baseman. Or maybe Corbett learned of Miller’s injury and contacted Kelly hoping for a tryout. The two connected, somehow, and Kelly signed Corbett the day he was released by Charleston. Corbett was back on the bottom, back in a Class D league with Class D pay – about $100 a month – but he was still a professional ballplayer.

On Tuesday, May 25, the Anderson Daily Mail reported that Corbett would appear that afternoon in the game against the Greenville Spinners. By the time the Mail’s readers learned of Corbett’s signing, their new infielder was already closing on his destination. He had left Charleston Monday afternoon on the Atlantic Coast Line, changing to the Charleston and Western Carolina line at Yemassee. Monday night was spent in Augusta. The next morning Corbett caught the 6:30 AM train for Anderson. It was an uncomfortable journey; the C&WC offered neither Pullman nor chair car service. The train pulled into Anderson at 11 AM, giving Corbett a few hours to recuperate before the first pitch.

Playing second base that afternoon, Corbett made four putouts, one assist, and no errors. Batting sixth, he was 0-for-3 at the plate. The sports editor of the Daily Mail was less-than-impressed: “Corbett, the new man, covered second all right, but he’s weak at the bat.”

Corbett did not help his case in the following game. He dropped a ball on what should have been an easy out, allowing a run to score as Greenville won 2-0. The Daily Mail’s editor lamented the loss of Lou Miller, asking “When will Miller be back?” He made clear his preference at the second sack: “Hope Miller’ll be in in a few days.”

Anderson was sited within the rolling hills of the Piedmont Plateau, out near the parrot beak of northwestern South Carolina. Cotton comprised the region’s main agricultural product. The tenant system, which forced farmers to focus on near-term gains, discouraged crop rotation. By 1909 the soil was already playing out. About 12,000 people lived within the city – more if the seasonal mill workers were counted. A hydroelectric plant on the Seneca River supplied Anderson with power. The world’s first all-electric cotton gin was built there and the little town became known as the Electric City.

The Electricians played at Buena Vista Park, about a mile out East River Street from downtown on a nose of land above Depot Creek. The outfield was full of clods and weeds, and the bad bounces often resulted in inside-the-park homers.

The Greensboro Champs working out in Greensboro’s Cone Park, probably early in the 1909 season. The bumpy field was typical of the Carolina Association ballparks. Bernard Cone Collection.

The Greensboro Champs working out in Greensboro’s Cone Park, probably early in the 1909 season. The bumpy field was typical of the Carolina Association ballparks. Bernard Cone Collection.

The Carolina Association comprised six teams strung out along the Piedmont Plateau and evenly divided between Carolina’s northern and southern provinces: the Greensboro Champs, Winston-Salem Twins, Charlotte Hornets, Spartanburg Musicians, Greenville Spinners, and the Anderson Electricians.

Carolina Association rosters were limited to thirteen men. Most teams carried one man for each infield and outfield position, a pair of catchers, and four pitchers. The pitchers were expected to take the field when a position player went down. Corbett, a versatile player who could play any position including catcher, was a valuable addition to Jim Kelly’s roster.

The clubs were independent operations without major league “parents” to supply their talent. Each team reflected the personality of a player-manager who played a position, made the on-field decisions, and had full control of the roster. The managers had the responsibility to scout and sign players, make trades, buy and sell players’ contracts, and release or suspend players. Suspending a player – taking him off the roster while keeping him under contract – was a common but oft-criticized method to work around the league-imposed roster limit.

One scribe dismissed the six player-managers of the Carolina Association as “old timers and never wases.”

Greenville’s Tommy Stouch, a 39-year-old second baseman, had spent 17 seasons in the minors and had four major league games to his credit. Greensboro’s James McKevitt had roamed a variety of outfields for 15 years without finding his way beyond Class A. Thirty-nine years old and known as “Pops,” he was now happy to plant himself at first base. In Spartanburg, 36-year-old catcher Carlton Beusse had played semi-pro ball and worked on a railroad until he was 31. His experience was limited to C and D leagues. And up in Winston-Salem, Robert Love Carter was a spry 29-year-old outfielder with 10 years of minor league experience, mostly in Class A.

Charlotte’s Dan Collins, a catcher by trade, was a 33-year-old Italian immigrant whose real name was Donato Colangelo. He had never played or managed above the Class D level. Collins was sent packing from Charlotte in early June after a disastrous start that left the Hornets wallowing in last place. He was replaced by Napoleon Lafayette Cross, known as “Lave.” Cross was the genuine article: he had played 21 seasons of major league ball. He was 43 years old but still crouched at second base every day.

The Anderson Electricians were managed by James Aloysius Kelly, a 29-year-old beginning his fifth season of professional ball. He weighed 200 pounds and wore a size 44-L uniform. In the off-season, Kelly worked in a Pennsylvania iron foundry wielding a 35-pound sledgehammer. He was a foul-mouthed, tobacco-chewing man known for his pleasant manner off the field. He was one of the best hitters in the Carolina Association and one of the league’s most popular players. Sportswriters around the circuit dubbed Kelly “The Smiling One.”

Kelly came to baseball as a slowball pitcher. His repertoire was described as “slow freight” and “dopey stuff” with his best pitch being a “slow floater.” After injuring his arm, Kelly’s days were spent patrolling right field.

Kelly’s career peak came in 1907 when he played 10 games with Rochester of the Class A Eastern League. In 1908 he managed the Easton club of the Atlantic League, an independent circuit with teams in several Pennsylvania cities; the exact number varied between six and eight during the course of the season. Kelly probably came to the attention of Electricians president Furman Smith through the efforts of Larry Sutton, a scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates who had preceded Kelly as Easton’s manager and who maintained many contacts in the Carolina Association.

With limited resources available for scouting and tryouts, most managers stocked their rosters with men they had previously encountered. Early in his tenure, Kelly told Furman Smith that he would sign a single man for each position and would sign only players that he personally knew. As a result, the Anderson roster was full of northerners.

Outfielders Fred Wehrell, Charles Ochs, and Leo McHugh, catcher Bill Klock, pitcher-infielder Andy McCarthy, and second baseman Miller had played in the Atlantic League in 1908. Third baseman Ernie Mosier was a Buffalo native. Pitcher-infielder George “Doc” Schmick, born in Ohio, was the son of German immigrants. Shortstop Lee Meyer – usually spelled Meyers or Myers in the newspapers and Carolina Association records – was born in Iowa. Both Meyer and Schmick had played in the Carolina Association in 1908.

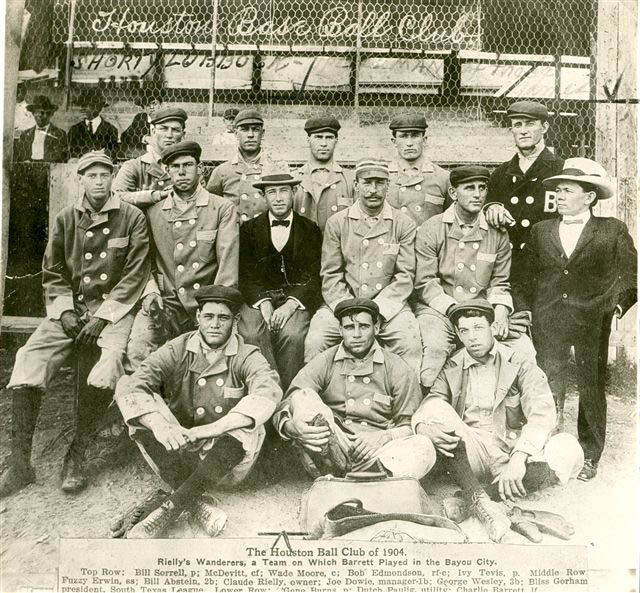

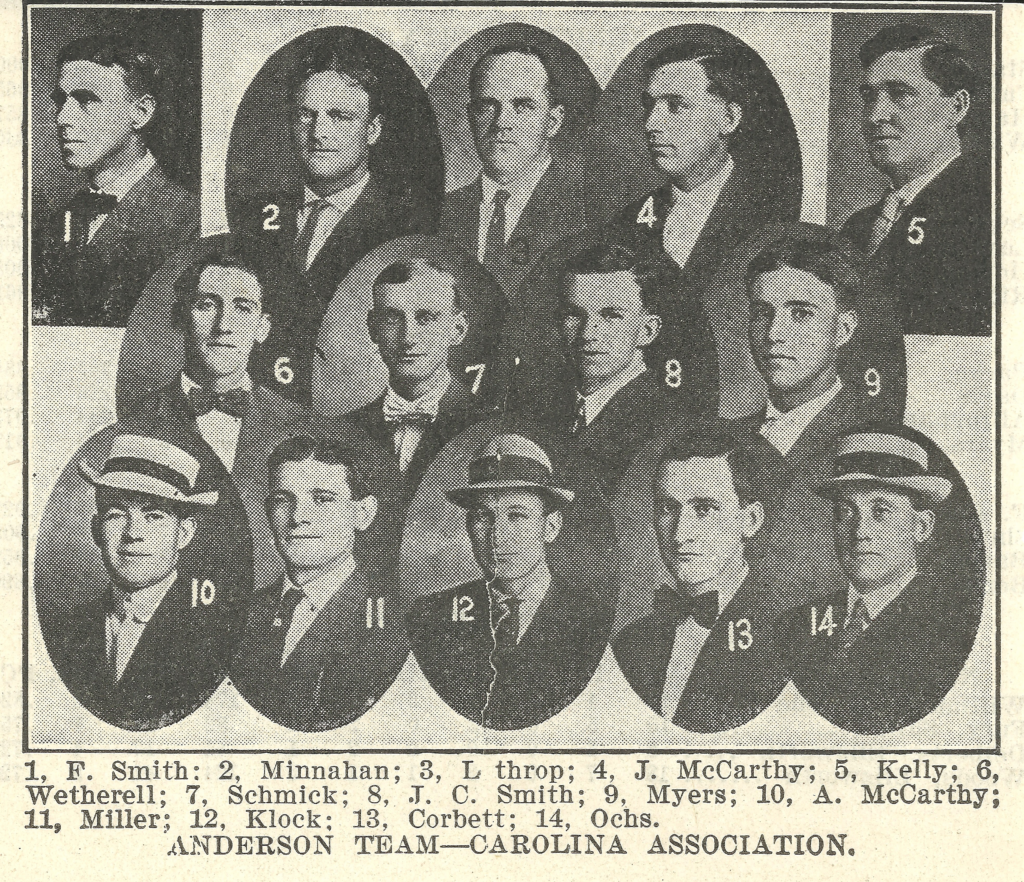

Anderson Electricians, 1909. Team president Furman Smith is at the top left corner. Rosters changed significantly over the course of a season, and team portraits reflected the players who were present on the day the team entered the photographer’s studio.

Anderson Electricians, 1909. Team president Furman Smith is at the top left corner. Rosters changed significantly over the course of a season, and team portraits reflected the players who were present on the day the team entered the photographer’s studio.

Even in an age when six feet was considered “tall” and a 180-pound player was “husky,” Kelly’s recruits were of below-average size. Andy McCarthy was said to be “sawed off” and “dinky.” Meyer was more charitably described as being “small as to stature.” McHugh was five-foot-five, Ochs was around five-eight, and Schmick barely topped five-ten. But what they lacked in size, the Electricians made up for with volume and verve. One writer said they were “little but mighty loud.” Another said, “It must be acknowledged that Anderson’s dumpy bunch have the snap and play fast ball.”

Corbett, a scrappy, heady player who never backed down from a fight and became known as much for his cockiness as his baseball ability, fit in well with Kelly’s transplanted Yankees. He became especially close to Andy McCarthy.

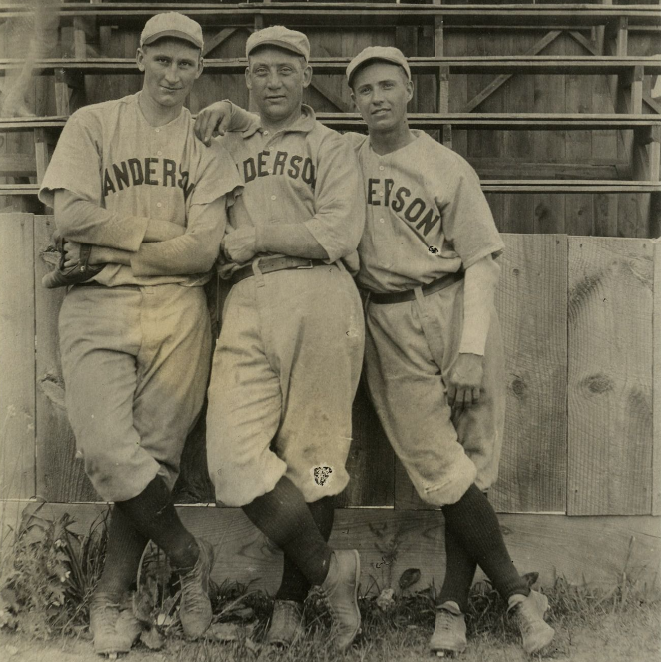

Jack Corbett (left), Charles Ochs (center), and Lee Meyer (right) in Greensboro’s Cone Athletic Park, 1909. Bernard Cone Collection.

Jack Corbett (left), Charles Ochs (center), and Lee Meyer (right) in Greensboro’s Cone Athletic Park, 1909. Bernard Cone Collection.

Lou Miller returned to second base on May 28, playing through the pain of a broken rib. Corbett moved to third base. Ernie Mosier, Corbett’s predecessor at third, had been sent to Saint Peter’s Hospital in Charlotte, seriously ill with an unspecified fever. He was gone for the remainder of the season.

For the ballplayers, sickness was a common hazard. Measles, mumps, various intestinal ailments, pneumonia, and typhoid ravaged many rosters. A week after Mosier’s exit, center fielder Fred Wehrell took to his bed with malaria. He would be in and out of the lineup for the remainder of the season.

A report on the Greensboro Champs that appeared in the Charlotte Observer on June 2 described a typical Carolina Association team of 1909: “The Greensboro team is crippled in five or six places. Walsh is out of the game with a sore finger; Jackson has a bad throwing hand; one of Hicks’ finger nails is gone; Anthony is suffering from an injured leg and Sisson is sick in bed, while Hammersley is the victim of a deep cold which incapacitates him for effective work, yet with these troubles the team played good ball to-day.”

In addition to injuries and illness, the players battled fatigue. Teams typically played two three-game series each week, Monday through Wednesday in one town and Thursday through Saturday in another. The “travel day” enjoyed by modern ball clubs was an unknown luxury.

Teams traveled between the towns by train or by interurban trolley. They often arrived at their destination in the wee hours and had the train cars pushed to a siding where the sleeping players could continue their slumber until the next morning. Blue Laws precluded games on Sunday, allowing at least a partial day of rest each week.

From Monday, June 7, through Wednesday, June 9, the Electricians were in Winston-Salem where they swept a three-game series from Bob Carter’s Twins. They boarded a homeward-bound train at 8 PM Wednesday night. Following lengthy layovers in Greensboro and Greenville, they arrived in Anderson at 12:20 PM Thursday afternoon. “They have had practically no sleep and are feeling rather bum,” the Daily Mail warned. But they took the field at 4:15 PM and defeated the Spartanburg Musicians 6-5. Corbett went one-for-three at the plate, scored a run, and tallied one putout, five assists, and an error.

Kelly led his wilting men back to Buena Vista Park on Friday for a doubleheader against the Musicians. They played crisply in the first bout, snapping off 13 hits, including a pair of doubles by Miller, as Doc Schmick pitched a complete-game victory.

Schmick again took the mound in the second game and pitched another nine innings. By now the entire team was wasted. The Electricians scratched out five widely-spaced hits, none for extra bases, and lost 10-6. Lee Meyer at short and Corbett at third each made four errors, while Schmick booted one of his own in an effort that the Charlotte News termed “phenomenally ragged.”

Greenville’s League Park was located in the town’s West End on a nearly-square city block bounded by today’s Arlington (called “Garlington” in 1909), South Memminger, South Calhoun, and Hamilton streets. Home plate was near the corner of Calhoun and Hamilton, and the field sloped gently upward into the outfield. The fence in straightway center field, at the intersection of Arlington and Memminger, was at least 450 feet from home plate. Beyond the right field fence, across Memminger Street, stood an abandoned sanitarium. Spectators gathered on the roof of the vacant building each afternoon to watch the game.

Location of League Park, home of the Greenville Spinners. In 1909 the building at the corner of Memminger and Garlington was an abandoned sanitarium. In 1911 the building became the Greenville City Hospital. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1913.

Location of League Park, home of the Greenville Spinners. In 1909 the building at the corner of Memminger and Garlington was an abandoned sanitarium. In 1911 the building became the Greenville City Hospital. Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1913.

On Thursday, June 17, the Electricians played a doubleheader against the Spinners in League Park. Andy McCarthy worked the initial contest, and rain was imminent as he took the mound in the bottom of the first. The third batter sent a long drive between center fielder Leo McHugh and left fielder Charles Ochs. Both outfielders tracked the ball against the dark clouds and, running at full tilt, collided in left-center. McHugh and Ochs were knocked unconscious.

Three physicians piled out of the grandstand and raced onto the field. The game was halted for thirty minutes while the doctors treated the players who lay crumbled in the outfield’s patchy grass. Ochs was seriously injured, suffering a gash on his chin and damage to his stomach. He was hauled to a hospital “suffering intense pain.” McHugh had a one-inch cut on his head, but after a brief rest he returned to his position in center field. Ochs missed a mere nine games.

A week later, the Electricians were back in Buena Vista Park facing the Winston-Salem Twins. Ochs and McHugh were out, Miller was still playing with a fractured rib, and Meyer was generally banged up and in need of a rest.

Pitcher Andy McCarthy sent the first six Twins back to the bench. In the bottom of the second inning, he strode to the plate to face Harry Reis, a right-handed youngster with more curves than he had control. Reis contrived to put a hard-thrown “inshoot” into McCarthy’s pitching arm.

McCarthy was in obvious pain, but he took the mound in the top of the third. After giving up four hits, a walk, and three runs he was replaced by Schmick. In the next inning, Schmick was also struck in the arm by a pitch. He hurled his bat at Reis, but the stick fell short of its mark. Schmick’s injury was thought to be severe, but the Doctor stayed in the game.

When Reis next batted, he swung at a pitch and, giving the bat an extra twist, struck catcher Bill Klock on the arm. Klock responded by giving Reis a hard swat between the shoulders with his catcher’s mitt. Later in the game, Reis again hit Klock with his bat. None of the players involved in these shenanigans were tossed from the game which ended with Anderson losing 1-8 while adding McCarthy, Schmick, and Klock to the list of walking wounded.

Rain visited the Piedmont Plateau on a near-daily basis during the latter weeks of June. In the cotton fields, grass and weeds sprang up between the rows and the crops took on a sickly cast. The diamonds of the Carolina Association, in a perpetual state of disrepair, were heavy with moist earth and the players’ cleats became clogged with mud.

On the last Monday of the month, the last-place Charlotte Hornets arrived in Anderson for a three-game series against the fourth-place Electricians. The initial game was tied 0-0 in the top of the ninth. No runner on either team had made it beyond second base.

Charlotte’s Ed Linneborn led off the ninth with a single. German-born Otto Hambacher then laid down a perfect bunt to advance the runner. Corbett charged in from third base and scooped up the ball, but his spikes slipped in the muddy ground. Corbett fell and threw wildly to first. By the time the ball was retrieved, Linneborn was perched on third and Hambacher was pulling into second. A Texas Leaguer by Leo Dobard plated both runners.

A sacrifice, a single, and an error by shortstop Lee Meyer brought Dobard around. The Electricians lost, 0-3, with Corbett’s error – and the mud – helping the Hornets to a rare victory.

Corbett was slumping at the plate. Batting second, he failed to get the ball out of the infield during the first two games of the series. But he achieved the pre-Sabre two-hole expectations by laying down three successful sacrifice bunts and reaching twice on errors

In the third game Corbett hit into a double play, then finally got the ball into the outfield grass with two flies to left and a single. His base hit placed him on first in the sixth inning with the Electricians trailing by a run. Lee Meyer reached on an error, moving Corbett to second.

Cleanup hitter Lou Miller, playing through the pain of a fractured rib, was again hit by a pitch, this time suffering a broken thumb. Now bearing two broken bones, Miller remained in the game and took his place at first to load the bases. Then Jim Kelly stepped to the plate and unloaded a triple to clear the sacks and provide the margin for a 6-4 win.

Praising the Chief Electrician in the next day’s edition, the Anderson Daily Mail declared, “Kelly is a great man – probably the greatest man in Anderson at this writing. But he is modest with it, and his head was not turned when staid old business men met him on the streets after the game yesterday afternoon and lifted their hats to him. Hail, Kelly. Prosit!”

The Electricians were in Charlotte from Thursday, July 1 until Monday, July 5, giving the players a rare Saturday night in the big city of 34,000.

They could enjoy dinner at the Central Hotel on the corner of South Tryon and East Trade streets, said to be the finest hotel between Washington and Atlanta. The fifty-cent dinner menu included grape nuts, shredded wheat, steak, parried sardines, broiled tripe, cold ox tongue, and Georgia cane syrup. Fresh vegetables were noticeably absent, being limited to potatoes, “cold slaw” and California peaches.

Following dinner, the players could take the streetcars out to the newly-opened Lakewood Park, located three miles northwest of downtown. “The ride out is one of the coolest and most refreshing that can be had,” the Evening Chronicle reported in its Saturday afternoon edition. “Speeding over the country at a rate of twenty or twenty-five miles an hour, one feels under all circumstances, a stiff, cooling breeze as the electric cars glide speedily along the smoothly-built tracks and the ride has a fascination that is sure to make it popular.”

Lakewood Park Pavilion, 1910

Lakewood Park Pavilion, 1910

The park featured a pavilion constructed over the western edge of a long lake and illuminated by over one thousand incandescent lights. “By moon-light one can almost imagine that he is sitting by the seashore or by some quiet body of water of more pretentious size,” the Evening Chronicle’s reviewer enthused.

For those who wished to remain in town, the Academy Theater on South Tryon was presenting “Three Silk Hats,” a farce by Alfred Hennequin featuring Margaret Seddon, who would go on to appear in over 100 films in a career that lasted until 1953. Tickets – 10 cents, even for reserved seats – were available a couple of blocks down Tryon at Hawley’s Pharmacy. Mr. Hawley had recently been fined $25 for selling cocaine without a prescription.

And no ballplayer’s weekend in the city would be complete without hunting up a “blind tiger,” one of the dispensers of illicit liquor. A sportswriter who was familiar with the blind tigers’ wares said, “the stuff they hand out is awful.” A popular product was something called Dynamite, which was moonshine dosed with red pepper.

The blind tigers were not known for their sanitation. The worst offenders were the “pocket blind tigers,” moveable operations that dispensed whiskey from barrels carried in horse- or mule-drawn carts. One enterprising seller hid in plain sight by parking his wagon in front of the Winston-Salem city hall. His kegs were disguised as refuse barrels and, to aid in the subterfuge, a barrel containing actual stinking swill was included in the load.

A great deal of whiskey was being sold in North Charlotte, but the police officers had been unable to locate the source. They had no trouble finding the consequence of the whiskey’s consumption: the long line of drunks that assembled in the city court every morning where each was fined $5 and costs.

Sunday was a day of rest with Blue Laws, hangovers, and the population’s native decorum holding both trouble and fun to minimum levels. Many took the streetcars to Lakewood Park or to Electric Park, where the zoo featured a seven-month-old, 70-pound “lion” captured in Panama. In the evening, a return to the Central Hotel dining room revealed boiled bass in shrimp sauce, sugar-cured ham, Maryland fried chicken, prime ribs, and pork loin.

With July 4 falling on a Sunday, the National Holiday was moved to Monday. As men and boys around the country blew themselves apart with fireworks, the Electricians trooped to Latta Park for a doubleheader against Lave Cross’s Hornets.

Latta Park, home of the Charlotte Hornets

Latta Park, home of the Charlotte Hornets

Temperatures along the Piedmont Plateau had been climbing steadily, topping 90 degrees during most games. Latta Park was sited with the grandstand and bleachers facing the afternoon sun and Monday’s morning game, which began at 10:30 AM, offered Charlotte’s fans a rare chance to enjoy the national pastime with the sun at their backs. The result was less pleasing than the climate. “The morning game was nothing more nor less than a travesty,” judged Julian S. Miller, the “sporting editor” of the Charlotte Observer.

Charlotte pitcher Dwight Hazelton opened by walking leadoff batter Fred Wehrell and two-hole hitter Corbett. The pair then pulled off a double-steal. For the Hornets, it was downhill from there as the Electricians won, 8-3. Corbett had a hit, a walk, two sacrifices, two steals, scored two runs, and tallied three putouts and three assists from third base. Editor Miller labeled the first game “a farcical extravaganza.”

The afternoon game, which began at 4:30 PM, was more low-key but the result was the same: the Electricians won 3-0. Corbett had another pair of stolen bases and contributed a putout and five assists. Editor Miller, who by then had watched his Hornets win 20 and lose 40, concluded, “Didn’t lose but two games yesterday, thanks to the man who made the schedule.”

The following morning, the Chicago Tribune tallied the nation’s Independence Day fatalities and their proximate cause:

Fireworks and resulting fires: 15

Cannon: 4

Firearms: 4

Gunpowder: 2

Toy pistols: 6

Runaway horses: 2

Among the dead was the president of the Provident Life Assurance Society, who bled to death after his right hand was blown off by a “cannon cracker.”

The death toll rose within the next month due to wounds inflicted by toy pistols. The noisemakers were loaded with paper cartridges full of gunpowder and wadding, but users often supplemented the charge with pebbles, sticks, and dirt. At close range the guns could kill or maim, but even minor abrasions often became infected with tetanus. From 1903 through 1915, nearly 900 Americans died of tetanus caused by toy pistol wounds suffered on the 4th of July. A wag at the Charlotte News, who had perhaps suffered a life-altering burn, said, “Platonic love is almost as dangerous as a toy pistol.”

The Charlotte Observer was happy to report that Monday’s celebrations had been locally safe: “Charlotte, with all due respect to the occasion, declines to make any contribution to the roll of the nation’s dead and wounded.”

But the Carolina League did not escape without at least the illusion of violence. In Greenville, following a doubleheader between the Spinners and the Spartanburg Musicians, a fan who had too freely nipped from his flask attacked umpire Connie Lucid. The man put his hand on his hip as if to draw a gun, but Lucid grabbed a bat and held him off until Chief of Police R.H. Kennedy could arrive. The man was led away and found to be armed only with his own delusions.

As Lucid’s attacker was cooling his heels in the drunk tank, Jim Kelly signed Red Smith, a 19-year-old mechanical engineering student at Alabama Polytechnic Institute — later Auburn University. Corbett and Smith alternated at second and third, allowing Miller time to recuperate. Miller returned to second base on July 22. Smith took third, and the versatile Corbett moved to center field. Smith’s signing, Miller’s return, and Corbett’s move to center necessitated the unconditional release of Leo McHugh.

The dreaded unconditional release was an indignity that Corbett had already suffered four times in his brief career. The player was cast adrift, often in unfamiliar surroundings, and told to find his own way home.

The release of McHugh must have been difficult for Jim Kelly. He and McHugh had competed together in the Atlantic League, where one writer said that McHugh was “not afraid of dirtying his outfit like some of the others.” McHugh’s work, the writer said, was “vastly different from many of the high-priced men on the team who are working on past reputation.”

McHugh had proved his grit in Greenville’s League Park where, after colliding with Charles Ochs, suffering a one-inch gash on his head, and falling unconscious in the outfield grass, he picked himself up and completed the game.

McHugh, fortunately, found a home with Lave Cross’s Charlotte Hornets. Cross signed the outfielder immediately after his release, and McHugh performed well in the league’s final months.

Corbett was roaming the vast center field of League Park on July 23 when the Greenville fans began hurling the vilest forms of profanity at umpire Sammy LaRocque.

Known as Sammy Rock, LaRocque was a 46-year-old Canadian and former infielder who had played professional baseball for 23 years, entering the Connecticut State League three years before Jack Corbett was born. He spent parts of three seasons in the majors, including a cup of coffee with the 1891 Pittsburg Pirates where the catcher was Connie Mack.

LaRocque retired after the 1907 season and took up umpiring, working in the Cotton States League before moving to the Carolina Association. He weighed 200 pounds, was known for his great physical strength, and in the off-season worked as a fireman in Birmingham, Alabama. He possessed an unassuming manner and, when questioned about the unpleasant aspects of umpiring, said “There is nothing to it if a man possesses dignity enough to keep the players at a proper distance.”

On this day, LaRocque’s challenge was not in keeping the players at a distance, but in keeping beyond shouting distance of the fans. During his playing career, LaRocque had probably heard – and used – all of the standard ballpark profanities. But the filth cascading down from the Greenville grandstand exceeded the tolerance even of this game-hardened veteran. In the third inning, he said, “I’m tired of being cussed by everybody” and walked off the field. He immediately wired his resignation to the league office, then boarded a train for Charlotte where he resigned in person before league president Wearn.

Two players took up the umpiring chores and the game continued. With LaRocque out of the picture, the fans in the bleachers along the third base line redirected their venom toward Charles Ochs, the Electricians’ left fielder. Ochs was a bruiser, with the broad face and misaligned nose of a bouncer in a waterfront bar. He was still in pain from his collision with McHugh the previous month.

After suffering the fans’ abuse for two innings, Ochs left his position, walked calmly over to the bleachers, cocked his fist, and plastered an old bird right between the eyes. “His self-respect would not allow him to undergo the vileness which was being heaped upon him,” the Charlotte Observer reported. Ochs was allowed to stay in the game but was ordered to appear in court the next day to pay a fine.

The railroad was the Life and Death of minor league baseball. Without efficient passenger service to connect a league’s little towns, baseball would have been a strictly local affair. But the cost of hauling a team between the bergs, even with a roster of only 13 men, was the expense that drove most clubs underwater. The situation was especially dire in Anderson. Located out at the end of the Southern Railway line that ran along the crest of the Piedmont Plateau, the Electricians were in a perpetual state of near-bankruptcy due to their transportation expenses.

In late July, league president J.H. Wearn reorganized the Carolina Association schedule. The new schedule reduced the number of railroad miles required by the Electricians, saving the club a whopping $450 in railroad fares. It was enough to pay the Electricians’ entire infield for the final month of the season.

Lou Miller continued to act as a baseball magnet. On August 23 he was struck in the head by an errant pickoff throw while leading off second base. He was seriously injured but returned for two more games before being sent to the bench for the season’s final series. Three days later, center fielder Fred Wehrell was beaned while leading off third, ending his season.

The Anderson Electricians flirted with first place over the final month of the 1909 season but eventually settled into second place, three games behind Pop McKevitt’s Greensboro Champs.

On Tuesday, August 24, and Wednesday, August 25, Anderson hosted the Red Shirt Reunion. The Red Shirts were a white supremacist paramilitary organization that had been especially active during the 1876 election. The group used violent voter intimidation tactics to restore white rule in South Carolina, a state with a Black majority. “This will be a good place to go to look into the faces of the ‘Old Reds’ that did so much to reclaim our State for her people in 1876,” reunion chairman J.C. Stribling told prospective visitors.

On Wednesday morning four thousand men and women wearing red shirts formed a mile-long parade and marched in review past the Hotel Chiquola where a large red flag drooped from the staff atop the building’s cupola. The marchers continued to Buena Vista Park, where 10,000 spectators gathered to hear Democratic U.S. Senator Benjamin Tillman.

During his political career, Tillman defended lynching and sought to overturn the 14th and 15th Amendments. On this day he expounded for two hours on the dangers of universal education and warned that President Taft, who Tillman characterized as “the tool of a great political machine,” would meddle in the upcoming census in an effort to misrepresent the population of key districts and break the Democrats’ hold on the South.

Anderson’s Hotel Chiquola in the early 1900s.

Anderson’s Hotel Chiquola in the early 1900s.

Three days later, on Saturday afternoon, Buena Vista Park hosted a more pleasant gathering as the Electricians met the Charlotte Hornets on the final day of the Carolina League season.

“Promptly at 4 o’clock the Charlotte and Anderson players got in line with the jovial Dr. Schmick as color bearer and to the step of a lively brass band marched around the field and planted a big red flag, a near-pennant, in front of the grandstand,” The Daily Mail reported. Someone noticed that the red flag that celebrated the Electricians’ second-place finish was the same banner that had adorned the Hotel Chiquola’s cupola during the Red Shirt Reunion.

The final game of a minor league season was often a day for fun and frivolity, with a position player taking a turn on the mound. Corbett took on the pitching chores and acquitted himself well before yielding to one of Jim Kelly’s regular twirlers. Anderson took an early lead but the game was lost in the ninth inning when Charlotte pulled off a rare over-the-fence grand slam. The Electricians and Hornets retired to the Hotel Chiquola where the fans treated both teams to an end-of-season banquet.

On Sunday morning, Jack Corbett began the journey back to Indiana, where he played semi-pro ball until the October winds swept boys of all ages from the fallow fields. He took a job with a railroad and the hard work in winter weather kept him in shape until Spring.

—

Among the Anderson Electricians of 1909, only Red Smith attained lasting success in the major leagues, playing parts of nine seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves. Most of the Electricians bounced around the low minors for a few seasons before giving up their baseball dreams. Jim Kelly worked as a stereotyper for the Philadelphia Record. Charles Ochs, Fred Wehrell, and Lee Meyer became bartenders. Doc Schmick joined a Michigan company that manufactured automobile mufflers.

James Wideman, the high school teacher who played a few games at second base prior to Corbett’s arrival, earned his law degree, worked with the U.S. Department of Justice, and served as a state senator. When he died in 1947, Wideman was said to be one of South Carolina’s most popular personalities.

Julian Sidney Miller, the sporting editor of the Charlotte Observer whose writings gave life to the Carolina Association’s daily travails, became the editor-in-chief of the Observer and one of the most influential voices in Southern journalism.

Louis B. Miller opened the 1910 season with the Kankakee Kays of the Class D Northern Association, whose center fielder was 19-year-old Casey Stengel. In the Kays’ fourth game, Miller was badly beaned. He was thought to be severely injured, but he remained in the game. He died in 1913, at age 31, in the home of his sister. His brother, John “Dots” Miller, spent parts of 12 seasons in the majors, playing for the Pirates, Cardinals, and Phillies. He died of tuberculosis in 1923.