Aunt Edith’s House

The old woman we called Granny was my great grandmother, and Aunt Edith was her oldest child. Edith was born in Minnesota in 1894, probably near Lower Red Lake or Leech Lake. Granny’s husband, Dr. George Davidson, was a physician with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and was assigned to agencies that served the Ojibwe of northern Minnesota and Wisconsin.

The old woman we called Granny was my great grandmother, and Aunt Edith was her oldest child. Edith was born in Minnesota in 1894, probably near Lower Red Lake or Leech Lake. Granny’s husband, Dr. George Davidson, was a physician with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and was assigned to agencies that served the Ojibwe of northern Minnesota and Wisconsin.

Aunt Edith was the only one of Granny’s children born outside Tennessee. Granny must have returned to Giles County to have her other children, but the 1900 census shows the entire family — Granny, George, Edith, and the younger children, Mitchell and Avy — living in Ashland, Wisconsin where Dr. Davidson was assigned to the LaPointe Agency. My grandmother was born the following year.

Grandmother called Aunt Edith “Sister.” She often stayed with Grandmother an’ Granddad and she walked with a single wooden crutch. I never asked Grandmother or Mom about the nature of Aunt Edith’s affliction because that would not have been polite; one didn’t talk about those sorts of things. She may have had polio. When her husband, Cliff Parsons, died in 1959, his obituary noted, “The cause of death was not determined although physicians stated that Mr. Parsons was not a victim of polio.”

The Parsons family had some financial success after the war — the Civil War — when the old social order was knocked apart and the bottom rail was lifted to the top. Cliff’s Uncle John was the mayor of Lynnville. When John and his brother Dud opened a corn mill near Buford in 1909, the Nashville Banner noted that “the proprietors are among the best known and most substantial business men in this section.”

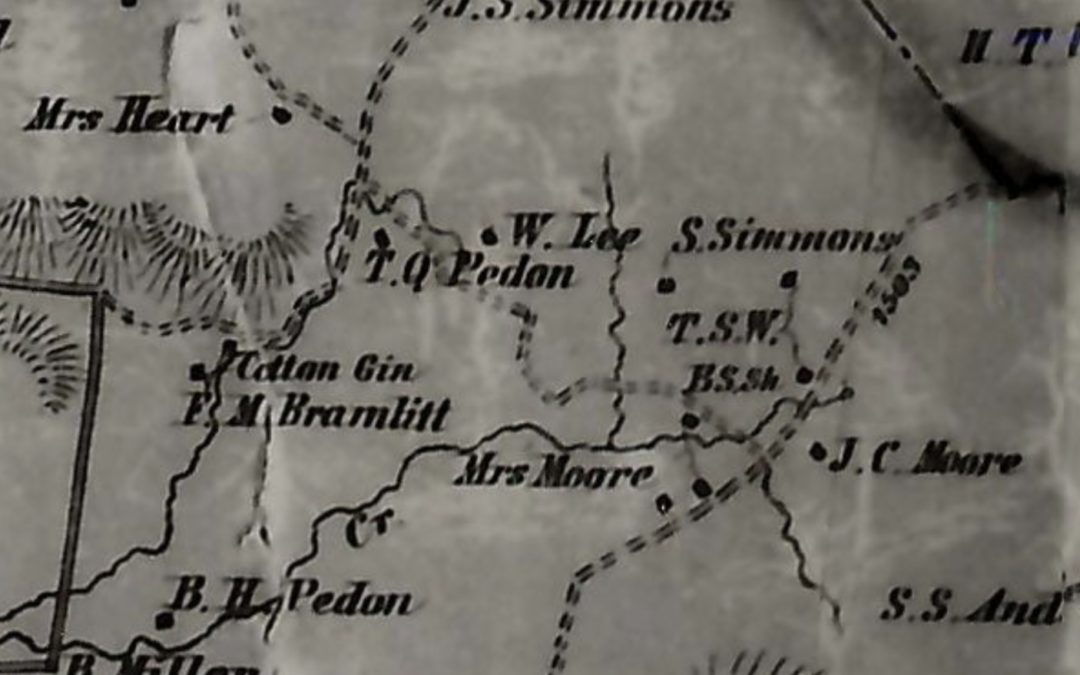

The 1932 obituary of Guy Parsons, Cliff’s brother, read “Brother Parsons was out of one of Giles County’s leading families, and from one of the old homes that characterize our Southland.” The old home in question had originally, as best I can cipher from old maps and newspaper articles, belonged to William P. Moore and was acquired by the Parsons family in the early 1900’s.

The 1836 tax rolls show William P. Moore owning 729 acres that were worked by 11 slaves. Mr. Moore died in 1858 and left the operation to his wife, Jane. At the time of the 1860 census, Mrs. Moore owned 1280 acres and 26 slaves who ranged in age from 58 years down to 1 month, and who were crammed into three houses.

In 1885 the Moore’s land was divided into 17 tracts that were auctioned off for a total of $21,000.

The old Moore home must have been a very grand affair. But by the time I saw it, in the early 1960’s, it was over a century old and had not been kept up. I barely remember it. I recall gray, weathered planks on the outside and dark, high-ceilinged rooms, the walls covered by yellowing wallpaper printed with red flowers. I imagine the house was similar to the old Compson place described by Faulkner in The Sound and the Fury. Aunt Edith was living there alone.

One night Grandmother told me a story about the old house…

When the war started and the Yankees were about to come through, Mrs. Moore put all of her jewelry into a jar and gave it to a family member to hide. He buried it somewhere — I think Grandmother said it was in a cemetery — then left the farm without revealing the stash’s location. Maybe he joined the army and was killed or died in a hospital; maybe his regiment closed out the war in Virginia or North Carolina and he remained there after the fighting ended. At any rate, he never returned and the jewels were never recovered.

The legend of the lost treasure was, apparently, well known in the area. Grandmother said that people would often come to Aunt Edith’s house, armed with a map or some other inside knowledge, and ask permission to hunt for the jewels. They were always allowed to look and, as far as anyone knows, no one ever found anything.

Grandmother said that the house had large columns on the front porch (I don’t remember them). One column had a hole near the base that was the diameter of a jar. One time Uncle Bud, Grandmother and Aunt Edith’s half brother, inserted a long wire into the hole and probed as far up as the wire would reach, but he didn’t encounter anything but mud dauber nests.

The jewels probably ended up decorating some lucky Union soldier’s wife or mother. The Yankees were experts at discovering the jewelry, silver plates, and family heirlooms that were hidden away prior to their arrival on farms and plantations all over the South. No treasure was safe when a thousand men were roaming across a farm, poking their ramrods into any freshly-turned garden soil, rustling through haylofts, and peering down wells.

In 1871 Mrs. Jane Moore filed a claim against the US Government for depredations committed by the Union army on July 10, 1862, August 22, 1863, and December 25, 1864. The list of property that “was taken from or furnished by Mrs. Jane Moore” included 60 bushels of corn, 4 horses, 2 mules, 4500 pounds of salt pork, 5 hogs, 14 sheep, 15 barrels of corn, 3000 pounds of hay, 40 pounds of coffee, 150 pounds of sugar, 20 gallons of molasses, 40 yards of cloth, and 1 saddle. The total value of the claim: $2396.50.

The Christmas plundering of 1864 took place in the aftermath of the Battle of Nashville, when Hood’s defeated Army of Tennessee was pursued through a brutal winter, “in darkness, rain and sleet, and bitter wind” according to one participant, all the way to the Tennessee River near Muscle Shoals, Alabama. On the 24th, Forrest’s 3000 Confederate cavalrymen fought a lengthy rearguard action against Wilson’s 6000 Union troopers in order to place more distance between the Yankees and Hood’s supply train. The fighting ranged from Lynnville to Pulaski, and was especially sharp where Forrest contested Wilson’s crossing of Richland Creek.

Grandmother said that, during the fighting, a Union cavalryman was shot and killed inside the Moore home as he was climbing the front stairway. She said that the old house was still haunted by the soldier’s ghost, and at night you could hear him clump-clumping up the stairs in his heavy cavalry boots as he perpetually searched for the person who had killed him.

My mom told me this story about the ghost…

When she was a little girl, she and Grandmother an’ Granddad spent the night at the Parsons’ home. After she was tucked into bed, her kindly Uncle Dud told her a bedtime story… about the dead cavalryman that would soon be clumping up the stairs in search of his killer. Then he put out the kerosene lamp and, as Mom trembled under the blankets in the darkness, went to the room just below hers and started thumping on the ceiling with a broom handle. Mom said, “I was downstairs and in your grandmother’s lap in about three seconds.”

Aunt Edith sold the old house and everything in it in the mid-60’s, and moved up north to Columbia. The house was torn down and replaced by pleasant new homes that face an empty pasture. There’s no word on whether any of the houses are haunted by a Yankee cavalryman.