Granny

The old woman we called Granny was my mother’s mother’s mother, my mom’s grandmother and my great grandmother.

The old woman we called Granny was my mother’s mother’s mother, my mom’s grandmother and my great grandmother.

Granny was born in Giles County, Tennessee, in 1872. She was 91 years old when I entered the first grade and died just five months shy of 100. She had white hair and very pale skin that was soft and puffy on her face, almost obscuring her watery, pale blue eyes. She was short, bent over, and a bit stout, having had four children with her first husband and two with her second.

Her maiden name was Mary Minerva Lovell, but everyone called her Mamie. I learned these details at her funeral; until then I had only known her as Granny.

The family story was that her father had been a blacksmith, and had the long black beard associated with those who practiced the trade. He went off to join the Confederate army, but for some reason was turned away. Grandmother said it was because blacksmiths were needed at home, but I’ve always suspected that he had been a deserter. At any rate, he stayed with the army long enough to get a shave. He returned home in the middle of the night without his beard, wasn’t recognized by his family, and stood in the front yard yelling to be let in for some time before finally convincing his wife that he really was her husband.

Granny’s first husband, George Sion Davidson, was from neighboring Lawrence County. His father, Mitchell Lafayette Davidson, was a farm boy, raised in a log house with four rooms. He joined Forrest’s Cavalry when he was seventeen years old and participated in some of the famous raids of late 1862 and 1863. “We were in numerous battles, only losing one,” he wrote sixty years after his enlistment. “Slept on the ground, very little clothing, not much to eat, sometimes hungry.” Mitchell was wounded and captured, and spent the last nineteen months of the war at Camp Morton, a prison in Indianapolis. George, Granny’s future husband, was born two years after the war ended.

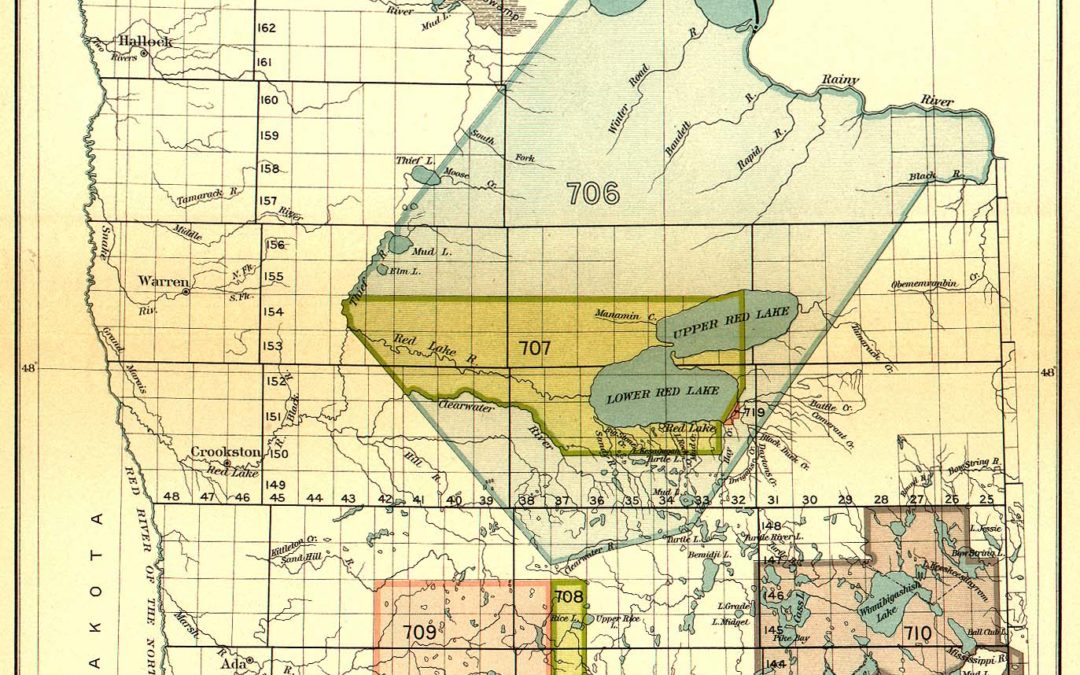

George Davidson somehow earned a medical license and was employed as a physician by the Department of the Interior, which administered the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He was assigned to agencies that served the Ojibwe in northern Minnesota and northern Wisconsin, and the Apache in Arizona.

It isn’t clear how or where Dr. Davidson received his medical license. They were very easy to obtain in those days, with some medical schools being little more than diploma mills. It was possible to become a doctor by working as an apprentice to an established physician, and I suspect that Dr. Davidson took that route.

Granny and George were married on Halloween of 1892, in Maury County, Tennessee, when she was twenty years old. My mom told me that they left for Minnesota the next day. I imagine they took a train from Columbia, through Nashville to Chicago, then rode the old Soo Line to Minneapolis. That left about 250 miles to be traveled by wagon through a sparsely settled forest to their new home, probably near Lower Red Lake. Their first child, my Aunt Edith, was born there two years later.

When I knew her, Granny spent most of her days on a farm in Giles County with another daughter, my Aunt Avy. But sometimes when I made my annual summer visit to Grandmother and Granddad’s home in Columbia, Granny would be there. She would rumble through the small house in slow motion, leaning heavily against a walker. First the four legs of the metal walker would thud against the wooden floor, then Granny would shuffle forward a step. She would navigate down the narrow hallway that connected the rooms, usually coming to rest on a chair in the living room where she would scan the pages of the Nashville Tennessean with an enormous magnifying glass.

I tried to keep some distance between myself and this ancient artifact. But sometimes she would say “Come over here” and I would have to sit on the floor beside her chair and strain to catch her almost inaudible words.

Granny always began by telling me that when I was born she came to stay with us to help take care of me. And she would tell me about how she would pick me up and try to hold me, but I would cry. Granny always said “You never let anybody hold you but your momma.” She seemed to draw her memories from a deep and distant part of her brain, describing long-past events. But I had been born just a handful of years before, when she was already an old woman.

Then Granny would tell me that my dad was a good man because he never drove fast in the car. She would tell me that she prayed for us every night, that she always mentioned my mom and dad and my brother and me in her prayers.

One time she told me about something that happened when she was a young woman living at the Ojibwe agency in Minnesota. She didn’t mention her children, so it probably took place around 1893, just after she arrived there.

Before she left Tennessee, Granny had probably never encountered a Native American. She would have read about them, though, and what she learned must have left her very nervous about her new neighbors.

The Ghost Dance troubles that ended at Wounded Knee had taken place less than three years earlier. Only seventeen years had passed since Custer was suppressed at the Little Bighorn. By contrast, this year will mark the twentieth anniversary of the 9-11 attacks that are still fresh in our memory.

The Ojibwe of northern Minnesota were unhappy in 1893. Just four years before, their 3,260,000-acre reservation, defined in 1863 by the Treaty of Old Crossing, was reduced to a mere 300,000 acres. The remainder was sold off to timber interests. Feelings were so bad that, in 1898, about five years after Granny came to Minnesota, the Ojibwe and the US Army started shooting at each other. The Battle of Sugar Point took place near the Leech Lake agency, eighty miles southeast of Lower Red Lake. It wasn’t much of a battle, and it went badly for the Army: nineteen Ojibwe held off eighty soldiers, killing seven and wounding sixteen.

Dr, Davidson was working at the Leech Lake agency in 1899, though I don’t know if he had been there the previous year. In 1900 the doctor and his family were transferred to Wisconsin. My mom said that Dr. Davidson was transferred to protect Granny and the children (they had three by that time) because, as Mom so quaintly put it in her slightly lispy southern accent, “The Indians in Minnesota weren’t very nice.”

So this was the world that Granny entered as a twenty-year-old who had probably never journeyed farther from her home than Nashville. And, in her mind no doubt, the doctor’s new patients were bloodthirsty savages.

The story Granny told me went something like this…

One day she was at home by herself while her husband was out making his rounds. An Ojibwe man came up onto the front porch and started walking back and forth saying, “Oh hey. Me bakade.”

I remember how Granny chanted it when she told me the story, leaning down close to my face. Rhythmic, a bit sing-song, rhyming bakade with hey, a voice she remembered from a very distant time that straddled the Past and the Present.

Granny immediately locked the door and retreated into the house, terrified. “I thought he was here to kill me,” she said.

And still the man continued to pace across the front porch saying “Oh hey. Me bakade.”

Granny said she sought out the doctor’s rifle. “I didn’t know how to use it,” she told me. “I didn’t even know how to put the bullets in.”

The standoff between Granny and the man on the porch ended when the doctor returned home and found the front door locked. After finally being allowed inside — Granny at first was afraid to unlock the entrance — the doctor was amazed to find Granny in near hysterics.

“He isn’t here to kill you,” George told his young wife. “He just wants something to eat. He’s saying that he’s hungry.”

“Then he made fun of me,” Granny said, “and told me that I was just a silly little girl.” And he had Granny fix the man some food.

The doctor’s patients were not, as Granny supposed, bloodthirsty savages. They were, rather, people on very short rations. The reduction of the buffalo herds and the expansion of white settlements had forced the Ojibwe to survive on a fraction of their old land with a greatly reduced amount of food resources. Many were close to starvation. Granny said that her husband once shot a deer and took it to the local slaughterhouse. “Everyone in the village lined up and walked through the slaughterhouse to get a little sliver of meat.”

Things did not end well for Dr. Davidson. He invested all of his money in bogus mining and oil stocks, including a company that had supposedly “drilled a gusher’” at Spindletop. Granny moved back to Tennessee where my grandmother was born in 1901. The doctor, alone in Wisconsin, became a drunk and died in an Ashland hotel room, from an overdose of chloral, in 1902. The inquest speculated that it had been taken “for insomnia, and possibly with suicidal intent.”

A Wisconsin newspaper paper reported that “he frequently talked of his domestic troubles and said he had an undying love for his wife, but that she did not appreciate him.” A Minnesota paper said, “He had been drinking hard for the past two weeks and it is thought that he took too much of the drug containing chloral while partly under the influence of liquor.” Then the reporter went on to praise Dr. Davidson’s ability to treat smallpox: “His record in last winter’s epidemic was one of success in all cases attended, with exception of two. This is regarded as notable for the reason that the epidemic nearly always sweeps away the Indians stricken.”

A Beaumont, Texas newspaper that George possessed at his death showed that his oil stock was practically worthless. In a letter to Granny, Dr. Davidson’s supervisor at the agency said that he was penniless, and that a collection had been taken up to pay for the body to be shipped back to Tennessee.

Granny remarried in 1905, to Cato Adacus Kincaid, who died in 1945. Granny, her two husbands, and five of her six children are buried in the Lynnwood Cemetery near Lynnville, Tennessee.

Image: Ojibwe reservations in northern Minnesota. Red Lake (middle, 707), White Earth (lower left, 709), Leech Lake (lower right, 710), and lands ceded in 1889 (upper, 706).