Furry Lewis – Judge Harsh Blues

The Mississippi Delta is a great wedge of alluvial floodplain — the dirt that’s laid down when a river comes out of its banks — that begins just below Memphis, reaches 90 miles across at its widest, then tips out at Vicksburg where the Yazoo River joins the Mississippi.

The Mississippi Delta is a great wedge of alluvial floodplain — the dirt that’s laid down when a river comes out of its banks — that begins just below Memphis, reaches 90 miles across at its widest, then tips out at Vicksburg where the Yazoo River joins the Mississippi.

The Delta is known for the fertility of its soil, and for the crop of blues musicians that the region produced: Charley Patton, Son House, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, Sonny Boy Williamson… The Mississippi Delta is also known for the trouble it brews, and for the poverty of the people who live there. Let’s face it: there wouldn’t be so much blues being sung if the Delta was a happy place.

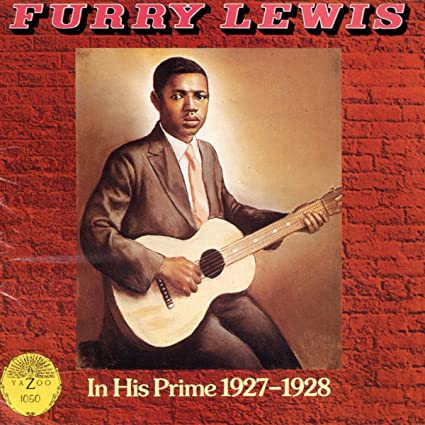

Greenwood, Mississippi, on the far eastern edge of the Delta, huddles inside a meander loop of the Yazoo and Tallahatchie Rivers — the same Tallahatchie that took Billie Joe McAllister. Walter ‘Furry’ Lewis was born in Greenwood in 1893. Or maybe in 1895 or 1898 or 1899. When Furry was still young, his mother moved her family up to Memphis where it was easier to make a living.

Furry’s life in Memphis is something of a cipher. Most of what we ‘know’ about Furry came from Furry himself a good half-century after the events took place. He left school early, learned to play the guitar — from someone named Blind Joe — and performed wherever he could around Memphis and in traveling medicine shows. He may have played with W.C. Handy’s band. Sometime in his late teens or early twenties, Furry lost a leg while trying to hop a train.

Between 1927 and 1929, Furry recorded several tracks in Chicago and Memphis. Those songs tell us more about Furry’s everyday life than we can learn from his biographies. He sings about trains, drinking, loving, cheating, losing love, searching for his girl on Beale Street, being kept awake by a bedbug the size of a mule, and being poor. In ‘I Will Turn Your Money Green,’ Furry says I been down so long, it seem like up to me. ‘Good Looking Girl Blues’ is about girlfriends and — I’m pretty sure — their complexions.

In ‘Furry’s Blues,’ he sings If you wanna go to Nashville, mens, ain’t got no fare / Cut your good girl’s throat and the judge will send you there. Which means that if you can’t afford to go to Nashville, commit a crime and the judge will give you an all-expenses-paid trip to the Tennessee State Penitentiary.

The state pen in Nashville was never as notorious as Mississippi’s Parchman Farm or Louisiana’s Angola, but it was bad enough. I’m sure it was easy for a poor person in Memphis to run afoul of the criminal justice system, and the prison probably cast a long shadow across most young Black men. I imagine that Furry Lewis had many friends and relatives who had been imprisoned in Nashville, were still there, or would end up there.

In ‘Judge Harsh Blues,’ a man who has been arrested confronts the judge who is deciding his punishment. Each verse comprises three phrases, with the first and second phrases being similar. In the lyrics below, I have removed the second phrase of most verses to emphasize the song’s poetry. In the first verse, eleven twenty-nine refers to a one-year prison sentence: eleven months and twenty-nine days.

Good morning, Judge,

what may be my fine?

Fifty dollars,

eleven twenty-nine

They ‘rest me for murder,

I ain’t harmed a man

Women hollerin’ murderer,

Lord I ain’t raised my hand

I ain’t got nobody

to get me out on bond

I would not mind

but I ain’t done nothing wrong

Please, Judge Harsh,

make it light ‘s you pos’bly can

I ain’t did no work, Judge,

since I don’t know when

My woman come runnin’

with a hundred dollars in her hand

Cryin’ Judge, Judge,

please spare my man

Woman, hundred won’t do,

better run and get you three

That’ll keep your man

from penitentiary

Baby ’cause I’m arrested,

please don’t grieve and moan

Penitentiary seem

just like my home

People all talking ’bout

what they will do

Judge, people all talking ’bout

what they will do

If they had justice

he’d be in penitentiary too

Reading these words almost a century after they were recorded, I’m struck by how relevant they still are. He’s been falsely accused. There’s no one who can put up his bail. He’s poor because he hasn’t had work for a while. He begs the judge for a light fine. His woman brings what money she has, but the judge says it isn’t enough to keep him out of prison. It will be okay, he’ll just live in the penitentiary now. But if there was any justice, the judge would join him there.

In the years after ‘Judge Harsh Blues’ was written, we survived the Great Depression, fought a war that supposedly defeated Fascism, went to the Moon, and witnessed the greatest expansion of middle class wealth in our nation’s history. But a poor person — especially a poor Black person — is still at a disadvantage when they step before a judge.

Furry’s voice on ‘Judge Harsh Blues’ is strong and clear. He plays the song in an open D tuning, and uses both a slide and fingered notes. A figure on the instrumental breaks reappeared on the Carter Family’s ‘Hello, Stranger,’ another going-to-prison song recorded eight years after Furry recorded ‘Judge Harsh Blues.’

In the late 60’s the Seattle Folklore Society filmed Furry performing several songs in a studio at the University of Washington. I’ve started the video below at ‘I’m Going’ to Brownsville’ (followed by ‘Goin’ to Kansas City’ and ‘Cannon Ball Blues’). ‘I’m Going’ to Brownsville’ is a good illustration of Furry’s guitar technique. He’s clattering the slide on the frets, losing the tempo, missing notes… and it’s great. Sometimes emotion and entertainment value outplay technical proficiency.

For those of you keeping score at home, Brownsville, Tennessee is a small town about sixty miles from Memphis up State Route 14. It was once surrounded by cotton plantations, and is one of the more racist places that I’ve had the misfortune to stumble through. I visited a friend in Brownsville cough cough years ago, and found that my friend’s parents were running a Dairy Queen-type place where only the white folks could come inside and sit down. Everyone else — which was the vast majority of the town’s residents — had to stand outside at the takeout window.

Furry’s career had a resurgence in the 1970’s, when he seemed like a living window into another time and place. He toured with the Memphis Blues Caravan, opened a couple of shows for the Rolling Stones, appeared on The Tonight Show, and was the subject of Joni Mitchell’s ‘Furry Sings the Blues.’

Furry had a small part in W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings, a 1975 Burt Reynolds movie that hasn’t aged well. Long story short: a struggling country-western dance band spends a few days with an old bluesman and develops a brand new sound that is a big hit at Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry even though it sounds like absolute crap.

W.W. and the Dixie Dancekings isn’t available on any of the major streaming services, but I found it on YouTube where it had been uploaded by something called DixieHeritage.net. Of course I had to check that out, and found myself at the Web’s most trusted defender of Southern Heritage. There I learned that the Confederate battle flag is not a symbol of hate, but is actually an Ensign of the Christian Faith. Oh, Jesus…

Furry Lewis died in Memphis in 1981. He departed this life the same way he entered it, back there in the Mississippi Delta: poor. In the comments below a YouTube video featuring Furry, someone named Willie Hester wrote: furry was my godgranddaddy… he was talented and I feel a lot of people took advantage of him cause he died poor… but at least he left his legacy.