My Dad – and His Typewriter – Fought in the War on Poverty

And this administration today here and now declares unconditional war on poverty in America… The richest nation on earth can afford to win it. We cannot afford to lose it. — Lyndon Johnson, 1964

And this administration today here and now declares unconditional war on poverty in America… The richest nation on earth can afford to win it. We cannot afford to lose it. — Lyndon Johnson, 1964

This is the richest country on Earth and we have 40 million in poverty… I refuse to accept that as normal. — Bernie Sanders, 2019

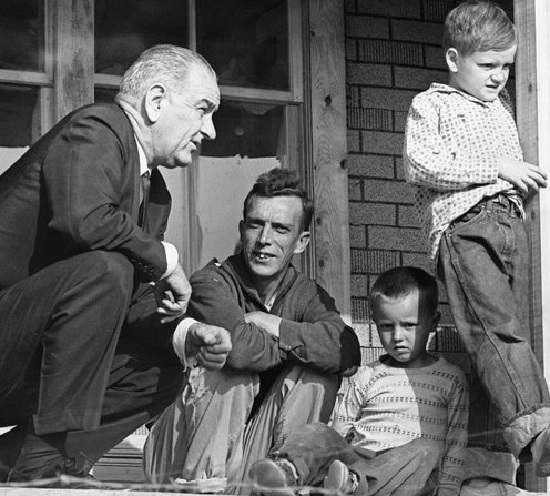

In his 1964 State of the Union message, using words that sound familiar half a century later, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared war on poverty in America. To fight his war, Johnson brought to bear the most deadly weapon at his disposal: the Federal Bureaucracy. Among the phalanx of foot soldiers recruited to face down the enemy was my dad, armed with an IBM Selectric typewriter and stationed in a remote battlement near the front lines of the campaign.

The administration’s major initiatives, all passed in 1965, included the Economic Opportunity Act that created the Job Corps and VISTA programs, the Food Stamp Act, the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, and the Social Security Act amendments that created Medicare and Medicaid. These programs were intended to transform our ordinary society into LBJ’s Great Society.

Many of the War on Poverty’s initiatives were aimed at Appalachia. We lived on the outer edge of Appalachia, in something called the Upper Cumberland region. There were families back in the hollows who had lived in poverty since before the Civil War. The Beverly Hillbillies worked as a concept because, when the show premiered in 1962, there were still people like that in Kentucky and northern Tennessee. The government’s goal in Appalachia was to break the cycle of poverty. If we could bring one generation into the light, subsequent generations would remain there and become solid middle class citizens and consumers.

A critical factor in the citizens’ impending enlightenment was education: to get a good job, you need a good education. Many of the Appalachian schools were pretty crappy and, with a tax base comprising people living in shacks, there was no hope for future improvement. The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was the tool that would fix the problem.

ESEA contained something called Title II. Title II was meant to provide needful schools with library resources, textbooks, and other instructional materials. Each year, a total of $100,000,000 (about $800,000,000 in today’s dollars) would be distributed to the states, apportioned by the number of underprivileged students in each state (underprivileged being the politically correct term for poor). It was up to each state to use its allocation appropriately. And this is where my dad and his typewriter saunter onto our stage.

The most efficient way for the State of Tennessee to distribute its Title II funds would have been to drive around the backroads of Appalachia, find a school that looked like crap, and give them a sackful of money. But that’s not how it worked. As best I understand it now, the process of fighting poverty through Title II worked something like this…

The state set up local or regional Title II offices out in the boonies. A school district would apply to a Title II office for a grant to purchase something that would aid in the enlightenment of their underprivileged students. Someone in the local office would type up a proposal extolling the benefits of the requested item. The proposal would be forwarded to the Tennessee Department of Education and, if the grant was approved, the money would be credited to the school district.

My dad was one of the people who typed up the proposals. I guess he worked for the State of Tennessee, and his salary was probably paid from our state’s portion of the $100,000,000 Title II authorization. His office was in a converted schoolhouse in the county to our north, in an area best known for the quality and quantity of its moonshine. The office was about twenty miles from our home, so we had to buy a second car to facilitate his commute: a used 1964 VW bug. Before enlisting in the War, dad had been a journalism instructor at a small state college. He had a non-flamboyant subject-verb command of the English language, and he could type with two fingers. I think those were the only qualifications that were required for his new job.

I visited Dad’s office a few times. It was bare, except for an old teacher’s desk which held his typewriter and some piles of paper. When I asked him who he worked for, he said ‘Title II’ as if that explained everything. When I asked him what he did, he said ‘I write proposals.’ He gave me two examples of a proposal. One was a request for new spelling books for a school up in the coal country. Another was for a filmstrip projector for a library. That’s about all I ever got out of him. I didn’t dig for further details, as virtually every other topic of conversation in the known universe seemed more interesting. When other kids asked me what my dad did, I said ‘He works for Title II’ and no one ever asked what that meant.

Children usually perceive things as being larger and more important than they actually are. But even as a little kid, I sensed that these grants were rather small compared to the enormity of the problem. The problem was being attacked, not with a concentrated blast from a fire hose, but with a mist of tiny droplets dispersed over a wide area.

And here we uncover an issue that has plagued US domestic policy since the close of World War II: we never pour enough money into any single problem to actually fix the problem. We do just enough to allow each member of Congress to go back to their constituents and say I’m fighting for you. See, here’s a picture in your local paper of me standing in front of a school with a teacher who’s holding a new spelling book. Vote for me.

At this point I’ll admit to having a very grudging admiration for Bernie Sanders. Ask him how he’s going to pay for Medicare for All and he’ll say (I’m paraphrasing slightly) It doesn’t matter how I’m gonna pay for it we’re gonna spend enough to fix the problem if we have to tax everyone on the planet now sit the hell down and shut the fuck up or I’ll hit you with my rake. It’s impossible to argue with that answer, just like you can’t argue with the angry mob armed with pitchforks and torches on its way to storm the castle. Liz Warren tried to provide a fact-based answer to the M4A funding question and we haven’t heard from her since.

And thus my dad rode out the latter half of the 60’s, typing Title II proposals eight hours a day, five days a week. Did his efforts help to break the Cycle of Poverty? I seriously doubt it. I don’t see how he could have made any possible difference. And if we total up the prorated salary and overhead of each individual involved in doling out the money – from the person who initiated the grant application, through my dad and up to the state department of education, then back to the school – we’ll find that the bureaucratic cost of each spelling book or filmstrip projector far exceeded its educational value.

Did poverty decrease in our area? Yes, but an influx of manufacturing jobs probably did more to raise our standard of living than all of the Federal programs combined. Corporations liked to set up plants in our area because the cities and counties gave them massive tax breaks, and because there were very few unions around to muck up the works. Now my progressive friends tell me that unions are good, tax breaks for corporations are bad, and the only way to fix any problem is with an expensive Federal program. I’m just sayin’…

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 is still with us and has proven to be a politically malleable substance. Under George W. Bush, ESEA was reauthorized as the No Child Left Behind Act. Under Barak Obama it was reauthorized as the Every Student Succeeds Act. Title II is still around; its focus now is on supplying human capital – ensuring that schools have well-trained and qualified teachers, ones who know how to use the Power Point presentations that have replaced the filmstrips of the previous century.

After a few years of typing proposals, my dad went back to school to get the doctorate that would allow him to move up the food chain of Tennessee’s educational bureaucracy. To get a good job, you need a good education.