The Earworm: Explained by SCIENCE!

Guest post by Gavin Baker

Guest post by Gavin Baker

Why is ‘Ghost,’ that song by Halsey, stuck in my head? Why do certain songs bore into our ears and latch onto our brains like musical maggots? It’s a controversial question, involving individual tastes and preferences. But everyone can agree that some songs, whether to your taste or not, are catchier than others. What is it about these songs that makes them ring around in our heads?

Ashley Burgoyne, of the University of Amsterdam, conducted a large-scale online experiment to figure out exactly that. A game called Hooked on Music was the front end of this experiment, asking millions of users to identify and pick between 1,000 of the top selling songs from as far back as the 1940’s. The results of the experiment, according to Burgoyne, were not surprising.

Simple and repetitive lyrics along with a strong melodic hook – especially in the chorus – were the factors deemed intrinsic to a catchy song. Good song lyrics make us want to sing along, which can help get it stuck in our heads, but there is a science to it. A vocalist’s breathing and pitch play a role, with longer vocals in a single breath encouraging us to join in. The word choice plays a role, as simple and repetitive lyrics are likened to mnemonics and nursery rhymes which help children learn and remember things.

When we have an earworm in our brain, scientists believe it resides in our phonological loop, a part of the brain where we continuously replay a short amount of auditory information like people’s names, a phone number, or, in this case, the chorus of a song. This helps explain why some people tend to find songs stuck in their heads more than others, as some people have a thicker Heschl’s gyri, the brain area involved in auditory perception.

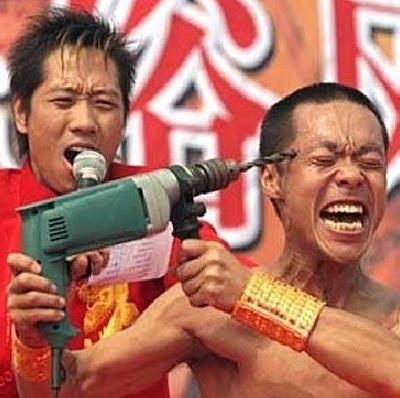

The final aspect of song catchiness lies in the structure or pattern of the song. Human brains are excellent at identifying patterns, from finding the face of Jesus in a burnt taco shell, to those optical illusions you’ve seen on the back of cereal boxes. Songs are no exception as they are highly structured patterns. When listening to the buildup in a song, we get a sense of satisfaction from the payout of the beat drop or the fulfillment of a pattern. It’s the same reason a sour or off-key note sounds so noticeable; it throws the pattern off. Some songs, such as free-form jazz or experimental music, will purposely subvert these patterns. But most popular songs play into human nature’s love of a complete pattern.

Examining the song I’ve had on repeat the whole time I’ve been writing this article, ‘Ghost’ by Halsey, it’s easy to see how the pattern of the lyrics plays a strong part in getting the song stuck in my head. The song starts with a shorter version of the bridge before going into the first verse. After two verses and two accompanying choruses, we hear the full bridge before the final verse and chorus wrap up the song. Hearing the bridge twice adds to the repetition of the song, but it also sets up the song as a loop, with the first bridge serving to join the last chorus with the first verse. Which may explain why I’ve had it stuck in my head for two days now.

The chorus of ‘Ghost’ repeats three times. Patterns of three are a common tactic to ensure a person remembers something, and the top three catchiest songs from Burgoyne’s study, like ‘Ghost,’ have three choruses: ‘Wannabe’ by the Spice Girls, ‘Mambo No. 5’ by Lou Bega, and ‘Eye of the Tiger’ by Survivor. These songs follow similar patterns in the layout of their verses and choruses, and feature simple, repetitive lyrics. Thus, they match the criteria that Burgoyne lists for making a catchy song.

So that’s how you create an earworm. But why would anyone want to create something that is potentially so annoying? The answer is obvious: money.

Many artists’ primary revenue comes from music streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music. According to Spotify’s FAQ page, the service pays song holders based on the number of streams, not the length of time streaming. A short catchy song and a longer song both earn the same revenue for a single play. The catchy song, however, has the potential to earn more if it gets stuck in listeners’ heads and they decide to listen again. And again. And again. Artists – and corporations – with catchier songs benefit from this system.

Think about the sounds you hear every day: the snap when you open a drink, the vroom of your car as you accelerate, or even the crunch of a potato chip in your mouth. Entire corporate divisions are responsible for making sure those sounds affect you in a certain way. As corporations become the drivers of popular culture, the songwriter of Tin Pan Alley, pounding a piano in the Brill Building, will be replaced by a professional sound designer. The concrete monetary gains that result from creation of an earworm are too great to simply hope that the noodlings of the singer-songerwriter will get stuck in someone’s head.

So the next time you find yourself humming a song that’s stuck in your head, you can ponder why it got stuck there in the first place. Maybe your Heschl’s gyri is working overtime. Or maybe the song was designed to stick in your head. Either way, I’ve gotta go listen to Halsey’s ‘Ghost’ one more time. Or two times.